Browse using the new Vinous website now. Launch →

Printed by, and for the sole use of . All rights reserved © 2015 Vinous Media

English Sparkling Wine: Effervescence and Reserve

BY ANNE KREBIEHL MW | FEBRUARY 10, 2025

Green and Pleasant Albion

“O, for a draught

of vintage! that hath been

Cooled a long age in the deep-delved earth,

Tasting of Flora and the country green…”

John Keats’ words are an apt opening to this report on English Sparkling Wine. What debuted in 1997 as a curiosity, with Nyetimber’s first release of their 1992 Blanc de Blancs, took just three decades to grow into a proper category. What is even more extraordinary than the rapid expansion of vineyards—an almost five-fold increase since the late 1980s—is the professionalism of this young but growing industry. Established players jostle with newcomers, presenting an exciting and delicious spectrum of traditional method sparkling wines that have come a long way, especially in the past decade. So let the corks pop and dive in.

Across the Gardens of England

While England’s sparkling pioneers all centered on the southeastern counties of Kent, Sussex and Surrey, with a far western outpost in Cornwall, the wines I tasted for this report hail from the west in Devon, Dorset, Wiltshire and Hampshire, stretch north of London to Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire along the Thames Valley, and reach as far east as Essex and the Suffolk Coast. There are currently 4,209 hectares of vines in the UK, most of them in England, with Kent, Sussex and Hampshire the leading counties. In 2023, sparkling wine made up 76% of the UK’s total wine production, 91% of which were traditional method wines. Thus, it does not come as a surprise that the most planted grape variety in the UK is Chardonnay (32%), followed by Pinot Noir (27%). Both varieties shine, especially Chardonnay. Many of the top-scoring wines in this report are Blanc de Blancs. In fact, the vast majority of sparkling wines in the UK are made from the three principal sparkling varieties, namely Chardonnay, Pinot Noir and Pinot Meunier, with Pinot Gris, Seyval Blanc and even Pinotage only making tiny contributions to the usual triumvirate.

Chalk, Greensand and Clay

When English Sparkling Wines first burst properly on the scene in the early 2000s, much was made of the chalk soils, drawing every possible parallel to Champagne. The fact that the Cretaceous chalk of Champagne dives below the English Channel and proudly greets visitors as the White Cliffs of Dover made this a particularly memorable illustration. But there is far more to England’s terroir than various kinds of chalk, as indeed there is in Champagne. In England, you find greensand (a kind of sandstone that’s also from the Cretaceous) and various clays. Having said that, I cannot tell the piece of soft, crumbly chalk I picked up in Avize (Côte des Blancs, Champagne) apart from the one I picked up in a Sussex vineyard. Site selection is key to ensure flowering and ripening in these northerly latitudes. In this respect, climatic factors are as decisive and often more important than subsoils.

A Burgeoning Industry

There is no doubt that English sparkling wine is a burgeoning category. In fact, “Viticulture is the UK’s fastest growing agricultural sector,” according to Wine GB, the industry’s representative body. But the buzz surrounding it needs context. Of those 4,209 hectares planted, 3,230 hectares are in production, i.e., actually bearing fruit, as there are many planted that are not yet productive. But even if we go with the bigger figure, that takes us to a nicely rounded, generous 4,300 hectares, or just under 11,000 acres. This is still smaller than Napa Valley’s Atlas Peak AVA (11,400 acres) or its Coombsville AVA (11,074 acres) and amounts to just 12.57% of the size of Champagne with its 34,200 hectares (84,510 acres) of vines. What is impressive, however, is the speed of growth in UK plantings. In 1989, when the public vineyard survey became compulsory, there were just 876 hectares of vines across 442 vineyards in the UK. Today, there are 1,030 vineyards and 221 wineries, with the biggest growth spurt occurring over the past decade. In terms of sales, sales of English sparkling wine totaled 6.2 million bottles in 2023, compared to the 299 million bottles of Champagne that sold in the same year. Context is indeed everything.

Eureka! Sparkling!

While the mild, moderate and maritime climate of England’s South Coast had long favored apples and hops as key crops, a few determined—if not to say bloody-minded—landowners and farmers persisted in growing grapes to make wine. Throughout the second half of the 20th century, these growers clung mostly to hybrids like Seyval Blanc or Germanic crossings like Reichensteiner, Huxelrebe, Bacchus and Ortega, counting on their ability to ripen on this cool, northerly island to make often off-dry, white Germanic-style wines. These wines were, I suppose, pleasant enough but could never really compete at an international level. It took two Americans, Sandy and Stuart Moss, to change the game. The Mosses purchased the Nyetimber estate in Sussex in 1986 and were the first to put two and two together, deciding to plant Chardonnay and Pinot Noir specifically for sparkling wine in 1988. This was England’s Eureka moment. Nyetimber released their first wine, a 1992 Blanc de Blancs, in 1997. The rest is history.

Foreign and Local Investment

It did not take long for this new sparkling Eldorado to evoke international interest. Attracted by then much lower land prices and climatic promise, the Champenois started prospecting in the mid-2000s, but the world financial crisis put a temporary halt to their endeavors. England received its final stamp of approval when Champagne Pommery planted 40 hectares of vines at their Pinglestone Estate in Hampshire in 2016. Champagne Taittinger planted 60 hectares to establish Domaine Evremond in Kent in 2017. In January 2022, sparkling wine powerhouse Henkell Freixenet bought Bolney Wine Estate in Sussex, and finally, in summer 2023, California-based Jackson Family Wines expanded into England, purchasing land in Essex for still wine production but buying fruit from Kent and Sussex to make sparkling wine. Even without this foreign investment, more and more money poured and still pours into England’s vinelands—so much so that real estate agents now have viticultural specialists. Within a short time, the industry has thus morphed from hobbyist to professional, and the wines have evolved along with it. All the while, the English leaned heavily on Champenois expertise and equipment—it is, after all, only a short hop across the Channel—while its own viticultural college in Plumpton in East Sussex is now a center for excellence that has spawned many star winemakers.

Challenges

Probably the greatest challenge of growing grapes in England is the low average yield, requiring similar cost and input as in Champagne but with a lot less grape juice to show for it. Climate is to blame. This is the case notwithstanding the mandatory planting density of 8,000 vines per hectare in Champagne and the generally lower planting densities in England (and assuming the same regimen when it comes to press fractions). While average yields in Champagne range between 50 and 75 hectoliters per hectare, the highest yields in England occurred in 2018 with 47.97 hl/ha (an absolute record), followed by 31.5 hl/ha in 2014 and 28.27 hl/ha in 2022. Even the record-setting year in England did not reach the lowest yields in Champagne. The average yield in England over the past 20 years was 22.25 hl/ha, with huge variations year on year. This volatility is the direct result of the high vintage variation in this still marginal climate.

English Reserve

These relatively low yields meant that most sparkling wines that were released in the early days were vintage-dated, simply because there were no reserve wines. It takes deep pockets to keep wines in reserve for blending in future years, and a large number of estates were dependent on the cash flow generated by sales, quite apart from the cost of keeping the wines. The poor 2012 vintage convinced many of the necessity to make multi-vintage blends. Bigger estates have also planted across counties to diversify their supply, while others purchase fruit from far and wide. Of the 107 wines I tasted for this report, only 30 are multi-vintage blends, as many new entrants find themselves in the same situation as more established players did a decade ago.

Green and Pleasant England

Then as now, new releases of the top English sparkling wines are still vintage-dated, as are the handful of prestige cuvées. Just four wines in this report are from the 2021 vintage, and a mere nine from 2020, with the majority from 2019 and 2018. These wines spent a decent amount of time on lees, affording the wines both balance and finer foam, key elements of quality. Even England’s warmer vintages (like 2018) come with lovely tension and briskness that is a real asset. The buzz, if not the hype, is justified. There are some world-class wines here. The best long-aged wines show the inherent quality of the fruit, with standouts from 2009, 2013 and 2014. In wines with both pre- and post-disgorgement age, there is no place to hide, and the brilliance, purity and youthfulness of these wines fill me with joy. The most beautiful aspect of this tasting, however, was the sheer diversity of styles, geographic origins and producers, indeed “tasting of Flora and the country green…”

Readers should note that there are just under 70 hectares of vineyards in Wales, but no Welsh wines were submitted for this report. I tasted most of the wines in this report in September 2024. A separate article on English still wines is forthcoming.

© 2025, Vinous. No portion of this article may be copied, shared or re-distributed without prior consent from Vinous. Doing so is not only a violation of our copyright, but also threatens the survival of independent wine criticism.

You Might Also Enjoy

Albion Gets Serious: English Sparkling Wine, Neal Martin, July 2020

Show all the wines (sorted by score)

- Ashling Park Estate

- Balfour Winery

- Black Chalk

- Bluestone Vineyard

- Busi-Jacobsohn

- Camel Valley

- Candover Brook

- Chapel Down

- Coates & Seely

- Crush & Brisk Ltd.

- Danbury Ridge

- Denbies

- Digby

- Domaine Hugo

- Emma Rice

- Everflyht

- Exton Park Vineyard

- Greyfriars

- Gusbourne

- Harrow & Hope

- Hattingley Valley Wines

- Henners

- Hundred Hills

- Langham Wine

- Leonardslee

- Louis Pommery

- Lyme Bay

- Nyetimber

- Plumpton Estate

- Rathfinny

- Ridgeview

- Roebuck Estates

- Sandridge Barton

- Silverhand

- Simpsons

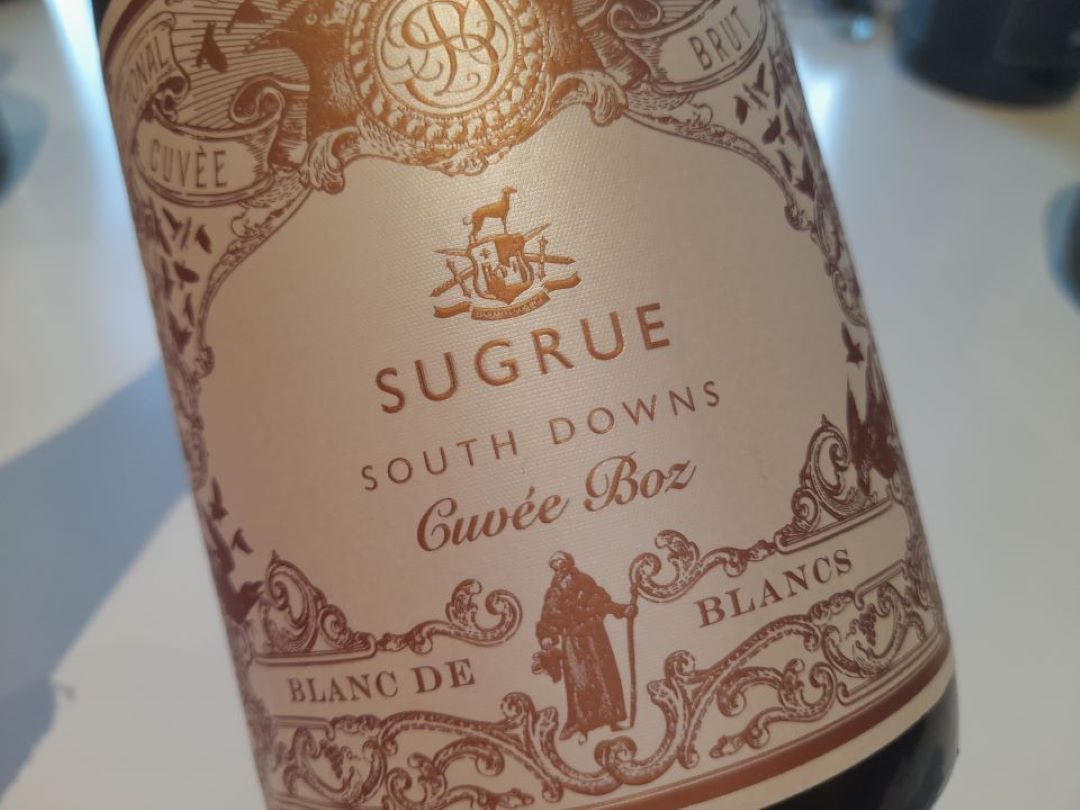

- Sugrue South Downs

- The Weyborne Estate

- Wiston