Browse using the new Vinous website now. Launch →

Printed by, and for the sole use of . All rights reserved © 2015 Vinous Media

On Music and Wine

In my second life, I am training as an operatic baritone. A few weeks back, I attended a masterclass led by Stephanie Blythe at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music, where I will graduate with a master’s degree this coming May. Stephanie Blythe is one of the most sought-after mezzo-sopranos singing today – a sensational interpreter of the works of Verdi and Wagner, as well as a champion of the American art song. I’d had the distinct pleasure of watching her perform the role of Mrs. Lovett in San Francisco Opera’s production of Stephen Sondheim’s classic musical Sweeney Todd the night prior.

Midway through the class, Ms. Blythe asked one of my colleagues to recite the words to her song aloud. She subsequently went on to compare singing to drinking wine. She explained that a singer, much like a wine drinker, must explore the way the text feels on the palate. Some pieces may be languorous and chewy, others rapid and tempestuous. Above all, a singer should harness this experience to better recognize the true nature of a work and to then convey it before an audience.

I was in awe. Until that moment, I would have bet good money that every conversation about mouthfeel in that concert hall must have been initiated by me. I’ve long felt indebted to music for helping me understand wine. But, I’d never considered the inverse —that wine could teach me about singing. As I traverse my two worlds, I’ve come to realize that the parallels between music and wine are both ample and of tremendous value.

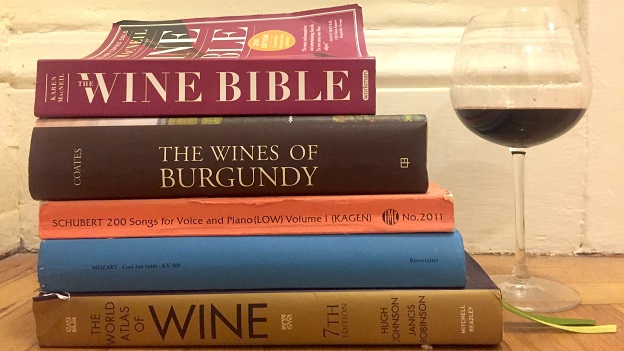

Coates, Johnson, Robinson, MacNeil, Mozart and Schubert, essentials in any wine or music library

Wine is a multi-sensory experience. We smell it. We taste it. We see it shimmer in the glass, and we feel it wash across our palates. The only sense we don’t use when evaluating wine is hearing. Thus, the comparison to music is vital in completing the metaphor.

Music, incidentally is only transmitted through our ears. Yet, as wine does, it holds the power to evoke the intangible. Music makes some people see colors. Gershwin famously set his Rhapsody in the key of “blue.” In his work Prometheus: The Poem of Fire, composer Alexander Scriabin went as far as to incorporate a “color organ” into the orchestra, illuminating the concert hall with changing lights to match the score’s harmonic progression. For those of us non-synesthetes, both music and wine have the ability to trigger past memories – transporting us back to the scents and sounds of our childhoods, our travels and beyond.

Comparing wine to music also helps us grasp the importance of complexity beyond flavor. Of course, a great wine will taste of many things from fruit to flowers, soil to spice. But, what keeps us engaged is the order in which these layers of flavors present themselves and how they transform on the tongue. Like music, wine has tempo, rhythm and dynamics. A great Napa Cabernet is like a messa di voce—a gradual crescendo to fortissimo, then slowly tapering back to a haunting whisper. Sancerre might have a subito piano, exploding as it enters, then swiftly hushing before its volume waxes again. And as the best melodies reverberate within us long after the piece has cadenced, the greatest wines live far past their finish, their expression so clear that they give us the power to taste them eternally.

Earlier in my education, I was introduced to Johann Gottfried Herder’s concept of Volksgeist, or “folk spirit.” The eighteenth century German philosopher theorized that people of a common national or cultural heritage share a collective consciousness. One gateway through which that primordial spirit may express itself is music. Herder would attest that for this reason Tchaikovsky’s oeuvre just sounds Russian. Or even if sung in English, Humperdinck’s opera Hansel and Gretel could never shed itself of its German-ness. This inexplicable phenomenon extends to wine. Italian wines, for example, are bound by a “good bitter” quality. Plant French grapes on the Tuscan coast, and somehow the soul of Italy will still beat strong at the heart of wines like Ornellaia or Sassicaia. Similarly a minty herbaceousness somehow permeates through much Australian Shiraz, even when the nearest eucalyptus tree stands miles away from the vineyard.

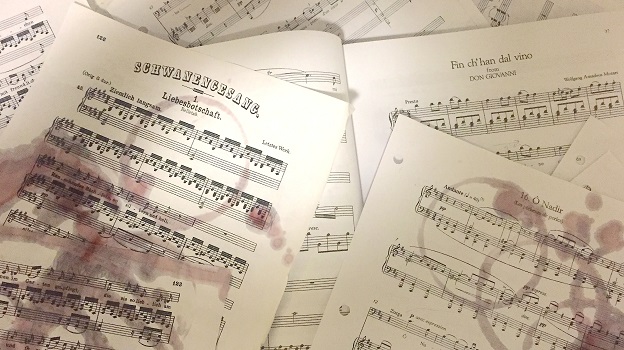

Staples of the baritone repertoire

We performers are often reminded of the humbling notion that we are but vessels through which music is communicated. As we sing, our individual interpretations undoubtedly color a piece. But ultimately, it is our job to preserve the purity of Mozart’s or Schubert’s or Puccini’s intentions and make their voice resonate even brighter than our own. Grapes are the same way. The most exemplary wines of the world are those that provide the most transparent window into the terroir in which they were grown. Like great musicians, classic grape varieties—Cabernet Sauvignon, Pinot Noir, Riesling—don’t rest on a singular identity, but rather best help us understand their myriad homes, old and new.

There was one thing Ms. Blythe said about wine that I didn’t fully agree with. She told us that like wine, a text should always taste good. Of course, for singers this remains fully sound advice. If a piece suits you poorly, your performance will be doomed from the start. But, for the listener not every moment need be immediately pleasurable. I think of the famous bridge that connects the third and fourth movements of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony. Beethoven builds anticipation so painfully tense, it causes you to writhe in your seat. But when he finally releases to a triumphant C Major arpeggio, its splendor feels ever more transcendent because he made you agonize first.

A great wine will do the same thing. It’s never one hundred percent delicious. It’s tainted with the flavors of things we’d never actually put in our mouths—pencil shavings, stale sweat, petroleum. Curiously, this is something we accept in wine that we don’t in food. We never want any portion of our meal to taste bad, just so the good parts taste better. Instead wine, like music, challenges us to think. Through the ugly noises and adulterated flavors, we come to better recognize what beauty really is. And isn’t that art’s highest purpose?

-- Bryce Wiatrak