Browse using the new Vinous website now. Launch →

Printed by, and for the sole use of . All rights reserved © 2015 Vinous Media

Finger Lakes Rising

As a former New Yorker, I’ve been excited to watch from afar as an increasing amount of acclaim has been lavished on the Empire State’s wine regions. In particular, the Finger Lakes has undergone an enormous transformation in the past 10–15 years as the quality of the wines has taken a gigantic leap forward. Like any other young appellation, though, pitfalls remain. In the case of Finger Lakes, three of them are anemic reds, imbalanced acidities and the clumsy use of oak. That said, there are so many truly excellent wines coming out of the area these days that consumers should be able to drink extremely well, and for relatively little money. Indeed, with every vintage it is more and more apparent that the Finger Lakes truly is becoming America’s premiere cool climate grape growing region.

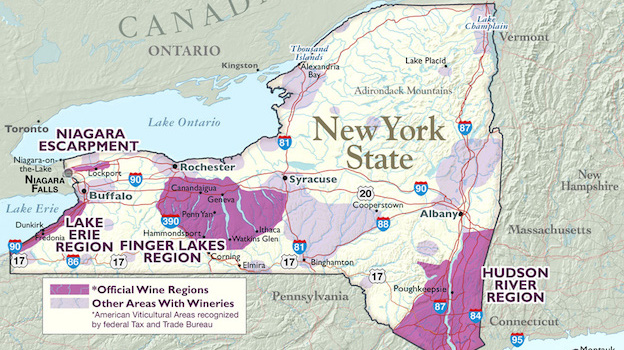

Making the Lakes

The Finger Lakes lie roughly five hours northwest of New York City. Like the wines, the scenery tends towards the austere, with miles and miles of farmland and forest interrupted by the occasional small town. The lakes themselves are quite striking, and have been attracting summertime tourists to their shores long before they were ringed with tasting rooms.

The idyll of Seneca Lake

The climate can be described as marginal at best, with brutally cold, extended winters that compress the growing season into a relatively short window. Viticulture is only made possible through the influence of the lakes; being extremely deep, they remain largely unmoved by seasonal temperature fluctuations, providing thermal insulation in the winter and a cooling influence in the summer. Indeed, proximity to the lakes is so essential to quality that the majority of the area’s vineyards are planted within actual sight of the water.

The other element that sets the Finger Lakes apart is the ground itself. While most of the region’s soils are variations on acidic shale, there is a distinct vein of limestone that wends its way down from Lake Ontario, occasionally intersecting with plantable land. Both the shale and the limestone can trace their origins back 550 million years, when much of eastern North America became submerged beneath the ocean. This area remained underwater for roughly 325 million years, slowly accumulating layers and layers of ocean floor on top of the continental plate. This seabed eventually compacted to form sandstone (compressed sand) and shale (compressed mud) in addition to limestone.

Most of the Finger Lakes vineyards are planted within actual sight of the water

Things took a dramatic turn roughly one million years ago, when the ice age descended and monumental glaciers pushed and scraped their way across the land, making permanent impressions that inform our current vistas. The particular glaciers that helped shape the Finger Lakes originated near Labrador and expanded due south, travelling at a rate of 2 – 25 feet per day. The Finger Lakes are, in effect, exactly what they look like-- claw marks, scratched out of the ancient ocean bed by the very ice whose melting filled them.

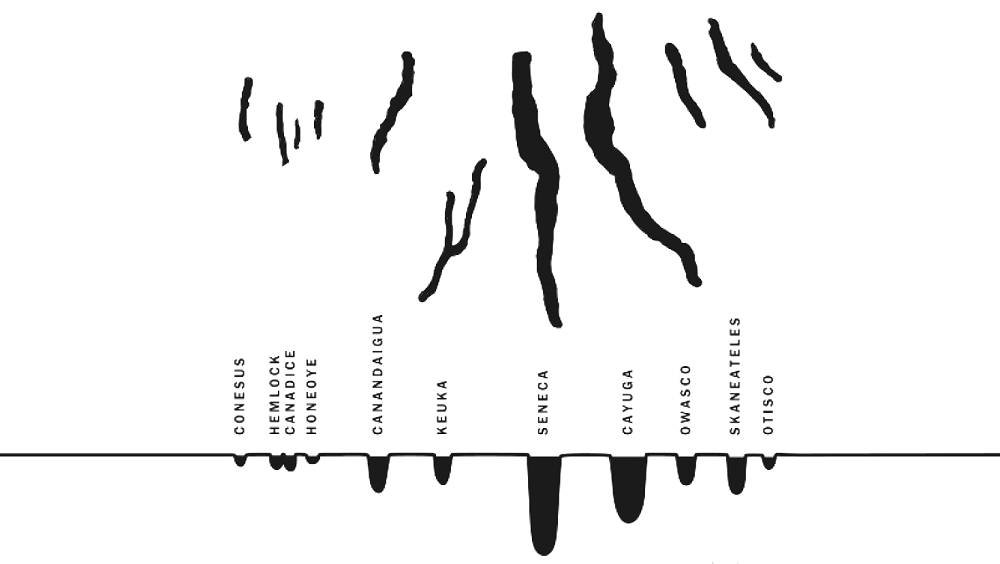

There are technically eleven Finger Lakes contained within the AVA, but only four are viticulturally significant: Canandaigua, Keuka, Seneca and Cayuga. Of these, Seneca and Keuka possess the greatest number of wineries and vineyards. At 632 feet, Seneca is the deepest, and therefore the most thermally stable; it hasn’t frozen over since the winter of 1912. Keuka is much more shallow (187 feet) and freezes over fairly regularly. While this makes it measurably colder. Keuka also boasts the steepest slopes, which help prevent the cold air from settling among the vines and causing damage.

The various lakes and their depths, courtesy of Hermann J. Wiemer Vineyard and Alexander Mergold

One particular patch of the Finger Lakes was identified long ago as ideal for viticulture. Known as the “banana belt”, this 4-5 mile strip of land runs along the east side of Lake Seneca. As weather tends to travel in a westward direction, cold winter breezes must cross the lake to reach the eastern shore, warming up a few degrees in the process. The slopes also face in a westerly direction, and are thereby exposed to the heat of the afternoon sun. Unsurprisingly, this area features the greatest concentration of vineyards in the appellation.

A Brief History of Wine Production in the Finger Lakes

Viticulture in the Finger Lakes started in the 1820s, but the area’s first winery didn’t open until 1860. The region quickly established a strong reputation for the quality of its sparkling wines, despite the fact that they were produced using native American grapes such as Concord, Catawba, Cayuga White, and Niagara. While these grapes are no longer employed for fine wine production, they still play an important role in the Finger Lakes, feeding the vats of the juice, jam, and sacramental wine industries. Manischewitz and Welch’s have played particularly important roles in the region’s history, with the Welch’s brand tracing its origins back to 1869.

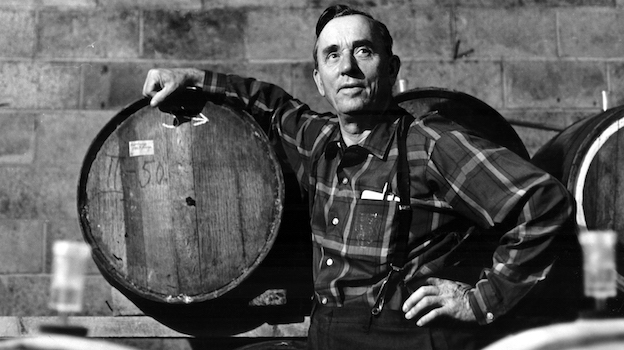

Dr. Konstantin Frank, courtesy of Dr. Frank Wines

French-American hybrid varieties such as Vignoles were introduced in the 1930s, largely through the work of Charles Fournier, a Frenchman who was wooed away from his position at Veuve Clicquot to head operations at Gold Seal, an important local winery established in 1865. While hybrids represented a significant jump up in quality, the wines they produced were hardly world-class. In 1954 Fournier, with the help of Dr. Frank, a Ukrainian native with a PhD in viticulture and a specialty in extreme climate vinifera cultivation, successfully developed the region’s earliest vinifera vineyards. The first bunches of Riesling and Chardonnay were harvested in 1957.

The winery and tasting room at Heart & Hands

A turning point in the Finger Lake’s history was 1976’s passing of the Farm Wineries and Cider Mills Low-Cost License Law (nicknamed the Farm Winery Act). The Act reduced both the red tape and the fee required to put up a bond, thereby allowing smaller operations to open and flourish. But perhaps even more critical to the development of the local wine industry was the clause allowing for direct-to-consumer sales. This opened the door for the tasting rooms, and the corresponding tourism, that has been the lifeline of the region ever since.

Bob (left) and Christopher Bates of Element Winery

When the big name wine brands began trading hands in the late ‘70s, it caused a disturbance in the grape market, inspiring many growers to start their own wineries and tasting rooms. Many seemed to employ a kind of something-for-everyone approach, producing a wide range of wines, often crafted in an easy, broadly appealing style. Only a handful of producers were truly striving for excellence on an international level. Happily, that is changing, and many of the producers to emerge in the last decade are thinking small, focusing their talents on modest quantities of higher caliber wines. Interest in sustainable farming and non-interventionalist winemaking is also growing. Christopher Bates, a Master Sommelier who launched Element Winery in 2006, was among the first members of this new wave. Seeking broader markets seems to be another hallmark of this recent crop of Finger Lakes producers.

Eminence Road Farm Winery is one of many new natural wine producers in the Finger Lakes

The sudden elevation in the quality of Finger Lakes wines has not gone unnoticed. Local boys who originally sought winemaking careers elsewhere are returning home, newly convinced of a bright future making Fingers Lakes wines. International winemakers are also setting their sights on the Finger Lakes. Louis Barruol of Chateau Saint Cosme in Gigondas joined forces with locals Justin Boyette and Rick Rainey to form Forge in 2011, which is producing some of the most polished and sophisticated wines in the appellation. More recently, in a move that has the whole region buzzing, California winemaker Paul Hobbs teamed up with Johannes Selbach of Germany’s Selbach-Oster to purchase and develop a vineyard at the southern tip of Seneca Lake. Hobbs has family ties to the area—his mother grew up in Ithaca and his parents met at Cornell—but his motivation was more about business than nostalgia. “I’ve been interested in launching a Riesling project for as long as I can remember,” Hobbs confessed, “and I thought that if any region within North or South America could produce Rieslings that might compete with Germany, it was the Finger Lakes.”

With all this new blood, overflowing passion, outsider investment, and the first blush of international acclaim, the Finger Lakes today calls to mind Napa Valley in the 1970s. Although tensions exist between the “old” and “new” ways of doing business, the collective feeling among the region’s producers seems to be a combination of excitement, pride, and anticipation.

Rick Rainey of Forge shows off his new vineyard site

Farming and Freezing

Of the region’s 9,000+ acres of vines, nearly 20% remains dedicated to Concord. Riesling is the second most widely planted variety with 829 acres — less than half of Concord’s total. The next four most prevalent grapes are also of native origin (Catawba, Niagara, Aurore, and Elvira), followed by Chardonnay in 7th place with 340 acres. All other vinifera varieties are present in minute quantities only, with 221 acres of Cabernet Franc, 179 acres of Pinot Noir, 105 acres of Gewürztraminer, and 29 acres of Lemberger (Blaufränkisch), among others. Hybrids represent a diminishing, smaller piece of the pie.

Farming vinifera vines in such a marginal climate is extremely challenging. The issues are not just frost sensitivity and maximizing ripeness, but avoiding the “killing freezes”— i.e. sudden drops in temperature that can actually cause the trunk of a vine to explode when the water inside freezes and expands. Even dormant, winter trunks contain some moisture, an amount that increases proportionally to the thickness of the wood. To combat this, vineyard managers have swapped one big trunk for a handful of little ones, with the oldest cut back every few years as a new one is trained to replace it. The graft joint where the vinifera trunk was fused to the rootstock is another spot vulnerable to frost. To protect it, vineyards are “hilled up” through the winter and spring, with the mounds of earth providing a layer of critical insulation. Also, as cool air sinks and forms pools on the ground, almost no vinifera vineyard in the Finger Lakes is planted on flat land. Indeed, the steeper the slope, the quicker cold air will drain, so many of the area’s top vineyards are planted on a significant incline.

A handful of smaller trunks is less susceptible to freeze than one large one

Of all the regions in the world, you might imagine that global warming would be a boon to the Finger Lakes, but instead it is wreaking havoc with growers’ peace of mind. “All global warming is doing is making the summers hotter and the winters colder,” noted Chris Stamp of Lakewood Vineyards. Oskar Bynke from Hermann J. Wiemer agrees. “The weather is becoming more and more extreme, with sudden, changeable events. All we can do to fight it is to try to build up resilience in the vines.” But damage from these weather events, especially frost, is inevitable, even within the most carefully tended vineyards. The last two winters have been especially brutal in the Finger Lakes, with hard freezes that caused damage to the dormant, embryonic buds. For more sensitive varieties like Gewürztraminer, the resulting crop loss reached as high as 90%.

Disease pressure is another critical issue for the region. Summer rains are common, and their effects can be devastating. More than one grower confessed that they often made their picking decisions not when the grapes achieved desired ripeness, but when they started to see botrytis (or worse) appear in the vineyards. Because of this, true organic farming is almost impossible.

Storm descending over Seneca Lake

All that being said, the quality of farming has improved dramatically in the Finger Lakes over the past several decades Chapitalization, a regular practice in the ‘90s, is still fairly common, but is not employed by most of the region’s top producers.

Wines and Styles

In my mind, there is no doubt that Riesling is the preeminent grape of the Finger Lakes. Truly excellent, world class examples can be found in all manner of styles—from sweet to dry to off-dry to sparkling. While this provides the consumer with a wide range of options, Riesling’s variable levels of sweetness can also be the very thing that turns consumers off. Thankfully, many producers in the Finger Lakes have adopted something called the IRF scale (short for International Riesling Foundation), which is usually displayed on the back label. Rather than simply listing the amount of residual sugar, this scale attempts to measure perceived sweetness, based on the ratio of a wine’s sugar to its acid. While by no means a perfect system (the difference between medium dry and medium sweet is not necessarily intuitive), it at least gives the consumer some idea of what to expect once the bottle is opened.

Budbreak in the Finger Lakes

Dry Riesling seems to be the preferred style of Finger Lakes producers. Many examples are superb. In some cases, however, the lack of sugar can make the region’s naturally high acidity seem shrill. In this light, it could be argued that an off-dry style might actually be the appellation’s strongest suit. Aside from a select group of producers who have mastered the unapologetically nervy style (Fox Run is an excellent example), the best dry Rieslings seem to come from producers intent on building texture into their wines, either through long fermentations, extended lees contact, neutral oak, an open mind to botrytis, or even a kiss of sugar.

During my tastings, there was a lot of talk about the potential of Chardonnay, but I remain skeptical. The majority of the examples I tried were either characterless and thin, or needlessly over-oaked. That said, I am holding out hope for the future, as there’s certainly no reason why the grape shouldn’t excel. In my opinion, Riesling’s second chair is undoubtedly Gewürztraminer. The natural austerity imparted by the weather prevents this heady grape from erring in a cloying direction, as it so often can when mishandled. The best wines I saw were perfumed but lithe, and probably the finest examples I’ve had outside of Alsace. Pinot Gris was another revelation. Again, the cool weather gives even the lushest Pinot Gris a chiseled quality that kept them lively and fresh on the palate.

Boundary Breaks’ young Riesling vineyard

Rosé is a category of growing importance to the Finger Lakes. The best I tried were bone dry in style but too many were rendered lazy through a surplus of residual sugar. Sparkling wines are a natural fit for both the climate and the soils of this region. I tried many fine examples, and certain producers such as Wiemer, Ravines, and Chateau Frank (a sub-brand of Dr. Frank) are operating at a very high level. Unfortunately, many producers of sparkling wine are disgorging on a rolling, “as needed” basis, which creates confusion and inconsistency in the marketplace.

There is some debate as to whether “the” red grape of Finger Lakes should be Pinot Noir or Cabernet Franc. Many top producers, especially among the new wave, are making a strong case for Pinot Noir, but the results are irregular. I can understand why they would persevere—more than once I caught a glimpse of that sublime something that only the best Burgundies possess. Most of the time, if the nose was exceptional, then the wine didn’t follow through on the palate. Or if the texture and finish were magical, the nose was out of balance. I suspect that the main stumbling block is farming, as Pinot Noir is quite sensitive to disease, moisture, and cropping, but whatever the reason, at this moment in time, Cabernet Franc is the safer bet. Indeed, most of the Cabernet Francs I tried were very good. Tannin management is an issue across the board, and, while some wines were aggressively vegetal, many were excellent. Perfume, finesse and a touch of something animal are all signatures. Lovers of Loire Valley Cabernet Franc will thoroughly enjoy what is on offer in the Finger Lakes.

Bloomer Creek’s reds are especially well-crafted

Lemberger, (Blaufränkisch), seems to perform well in this cool climate region. Rich in rotundone, the chemical responsible for black pepper aromas, the wines I tried were by and large extremely spicy, aromatic, and intense. When handled with a light touch, the best wines were delightfully expressive. When burdened with too much oak, however, the variety’s inner light seemed to dim. Tannin management is an issue here as well. A surprising number of producers are committed to making Merlot and Cabernet Sauvignon work. Though I confess to trying a couple of decent wines, the best were always from a hot vintage, which is something of a rarity. Otherwise, the wines were simply too lean.

Certainly other red grapes from various corners of the world might thrive in the Finger Lakes. There are experiments with Saperavi and Rkatsiteli (two Georgian varieties), Dornfelder and Teroldego. I tried very few excellent red blends during my trip. It seems elementary in such a marginal climate that the best route to a consistent and delicious red wine is through blending. Anthony Road’s unconventional blends of Cabernet Franc and Lemberger were particularly successful.

Red Tail Ridge’s stand of Dornfelder

Lingering Issues

Although I left the Finger Lakes energized by all the superb wines I tasted, several issues linger that are real stumbling blocks. These hurdles are significant: namely, farming practices and prices. These topics came up during almost every tasting appointment.

Farming remains a delicate issue in the Finger Lakes, especially among the new wave of young producers, the majority of whom don’t own vineyards. Many complained about the high yields insisted on by their growers, which can often result in diluted fruit and pronounced acidities. One solution is to replace tonnage contracts with acreage contracts, but not all growers are open-minded to such changes. Even so, assuming growers were amenable to such contracts, the simple truth is that even the best Finger Lakes wines can only command so much money in the market. While the current state of pricing represents an enormous value opportunity for consumers, low yields are hard to justify economically, while producers struggle to invest in better equipment that might further raise quality.

What is the solution? As a consumer I’m thrilled by reasonable prices, and would hate to see them escalate. But if the region is to continue progressing, a compromise must be struck. Certain brands such as Element and Forge, both of whom work with acreage contracts, are leading the charge in terms of demanding more for their product, and the execution is such that the customers have responded positively. But broader markets can be slow to move, especially one as reliant on local tourism as the Finger Lakes.

The long, tall stainless steel tanks at Hermann J. Wiemer Vineyard

Recent Vintages

The 2014/2015 winter was extremely harsh, with a hard freeze that damaged the dormant buds, and resulted in diminished yields. Naturally, this varied according to grape type and location, but many producers reported significant losses across the board. “We suffered at least a 50% crop loss,” Morten Hallgren of Ravines explained, “with the more cold-sensitive varieties such as Pinot Noir, Gewürztraminer, Sauvignon Blanc and Merlot faring the worst.”

Spring was cold and wet, though an uncharacteristically warm May got the growing season off to an early start. Massive rains – twice the regional average—fell in June, causing widespread disease pressure that was the Achilles heel of the vintage. Despite this setback, the summer finished on a rather warm, dry note, and the wines ended up riper than anyone originally thought possible. Bad weather in October forced some growers to pick their reds too early.

Johannes Reinhardt from Kemmeter loves the vintage. "I prefer ‘15 over ‘14. I think we are too much acid driven in the Finger Lakes, and a good Riesling doesn't need to show the acidity too prominently. I do enjoy ‘14, but they tend to be quite lean with stronger acidity. The 2015s tend to have more flesh on their bones, more substance, and more palate weight.” Rick Rainey of Forge agrees. “It is a powerful, rich vintage and will certainly bring great conversation about the potential of Riesling in the Finger Lakes.”

I too found the 2015 whites to be more substantial and powerful than what I sampled from other vintages. Despite the disease pressure, the quality is very high, especially among the Rieslings. Certain other varieties such as Pinot Gris are lacking a bit of vitality but all in all it’s clearly a very good year for whites. The reds, on the other hand, are a bit more variable in quality, likely due to either mildew, or insufficient ripeness. Cabernet Franc seemed to fare best.

The team at Red Newt, from left to right: David Whiting, Meagan Goodwin, and Kelby Russell

In my opinion, 2014 is a spectacular vintage across the board. It was a cooler season but not a forbidding one, and the wines – both white and red – possess that spark and vigor that fans of the Finger Lakes crave. I personally love the 2014s and find them to be quite vertical and exciting. The whites are certainly superior to the reds, but that is normal in such a cool climate region. That said, the reds are not to be discounted. Many are quite beautiful and perfumed, and are lightweight without being thin.

The growing season began dramatically, with a hard winter freeze that slashed yields. Spring was characteristically cold and wet, and the summer never really got too warm. Heavy rains fell in July, though the disease pressure was not as extreme as in 2015. “It was a comfortable summer, I hardly ever had to turn on the air conditioning,” Peter Becraft of Anthony Road remembers, “but in terms of ripening fruit it was a bit of a challenge. Coming into August I was worried, especially about the reds, because the acids were higher than the sugars. but then we had a warm, dry September and it all worked out.”

Nancy Irelan of Red Tail Ridge

Two thousand thirteen was a bumper crop year that got off to a cold, wet start. The summer was also quite rainy, especially June, and the temperatures were slightly cooler than average. The large crop struggled to ripen, and disease pressure was a huge issue, but a warm dry August and September helped things along.

Though I only tried a selection of wines from this vintage, the quality was rather middle of the road, though some seemingly random highlights are worth paying attention to. Both whites and reds tended to be lean and occasionally disjointed. As is often the case, the top producers such as Tierce, N. Kendall, Element, and Boundary fared best, making racy, invigorating whites and decently concentrated reds.

Steve Shaw of Shaw Vineyard

Two thousand twelve was an uncharacteristically warm year, one of the rare Finger Lakes vintages was that arguably better for reds than whites. Happily for the consumer, a good selection of 2012 reds is still on the market. The best are rich and almost full-bodied, with a ripe, broad texture and integrated structure. The whites are fuller than average, but not flabby. The Riesling have an attractive petrol edge to the nose, due to the heat of the year.

A warm, relatively dry spring got the season started early, and contributed to the longer-than-average growing season. The summer was warm but not hot, with the only significant rains coming in October. Among producers, opinions are divided on this vintage. Kris Mathewson from Bellwether refers to it as a “perfect year,” while Chris Bates from Element calls it “freakishly warm.” Morten Hallgren of Ravines, who tends to be among the last producers to pick admitted, “2012 is the only year I’ve harvested while there was still good weather ahead.”

The cellar at Ravines

For this report I tasted approximately 400 bottled wines during a trip to the Finger Lakes this past May, followed by several dozen examples at my home in June. Two excellent producers that I visited- Kemmeter and Red Tail Ridge-- declined to have their wines numerically rated so the reviews do not appear here.

-- Kelli White

Show all the wines (sorted by score)

- Anthony Road

- Barnstormer

- Bellwether Wine Cellars

- Bloomer Creek

- Boundary Breaks

- Damiani Wine Cellars

- Dr. Konstantin Frank

- Dr. Konstantin Frank - Chateau Frank

- Element

- Eminence Road Farm Winery

- Forge Cellars

- Fox Run Vineyards

- Fulkerson Wine Cellars

- Goose Watch

- Heart & Hands Wine Company

- Hector Wine Company

- Hermann J. Wiemer

- Kelby James Russell

- Keuka Lake Vineyard

- Keuka Spring

- Lakewood Vineyards

- Lamoreaux Landing

- McGregor

- N. Kendall

- Penguin Bay

- Ravines

- Red Newt Cellars

- Shalestone Vineyards

- Shaw Vineyard

- Sheldrake Point

- Silver Thread

- Standing Stone Vineyards

- Swedish Hill

- Three Brothers

- Tierce

- Wagner