Browse using the new Vinous website now. Launch →

Printed by, and for the sole use of . All rights reserved © 2015 Vinous Media

2014 & 2015 Muscadet: Contrasting Vintages Ripe for Discovery

BY DAVID SCHILDKNECHT | MAY 11, 2017

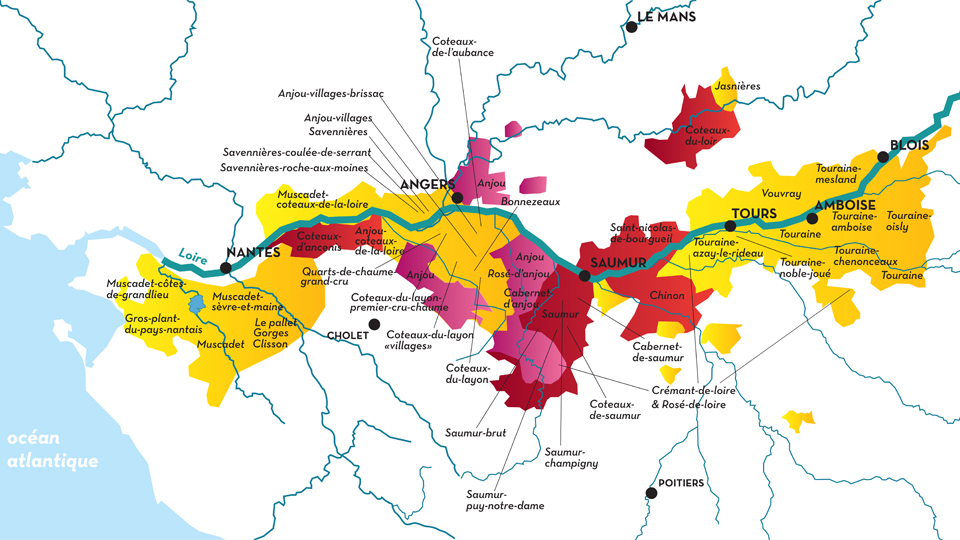

The Loire’s 600 miles drain almost one-quarter of France. Even restricting attention to those stretches of the river and its immediate tributaries that are most intensively cultivated means tackling an enormous territory with wide variations in growing season, soil and cépage—to name only the most obvious factors. As one striking contrast, not only do the habitats of Sancerre and Muscadet lie 200 miles apart as the crow flies (several times that many as fish swim) and grow strikingly different grape varieties but their production methods and styles also reflect enormous cultural differences. The former looks toward Burgundy (Chablis, featuring similar soils and climate, is a mere 50 miles distant) and the latter toward the Atlantic, its wine villages clustered around a metropolis, France’s sixth largest, that styles itself as the gateway to – and spiritual capital of – Brittany, a region with its own language and distinct history. (The city of Nantes was officially separated from Brittany in 1955 to become the capital of a newly created political entity: Pays de la Loire.) Contrasts of this sort render it misleading to even refer to “The Loire” as a single wine-growing region.

Covering the Loire for Vinous

Even to take traditional regional boundaries as a basis for reports covering wines of the Loire is problematic, since, for example, those sectors of Touraine that are devoted primarily to the cultivation of Cabernet Franc – Bourgueil, Chinon and Saint-Nicolas de Bourgueil – are best treated in tandem with adjacent Saumur, where that grape also plays a starring role. But to cover the Loire in reports focused on grape variety would preclude presenting discrete accounts of each important producer and his or her wines, since, for example, many of the top Saumur growers render profoundly complex wines from Chenin Blanc as well as from Cabernet Franc; and Sancerre, for all of its Sauvignon-centrism, is arguably home to France’s most important red Pinot Noirs outside of Burgundy.

I am accordingly dividing my coverage of the Loire into six reports. This first covers the Nantais, best known for – indeed, often treated as synonymous with – Muscadet, a wine sourced from Melon de Bourgogne, a grape that has traveled the world widely but achieves distinction solely in this place. Subsequent reports will cover Anjou (primarily Savennières and the dry as well as nobly sweet Chenins of the Coteaux du Layon); those appellations that feature Cabernet Franc but also grow impressive Chenin; Central Touraine (comprising Vouvray, Montlouis and the similarly Chenin-dominated Loir, spelled without the ‘e’); Eastern Touraine (whose wealth of cépages and stylistically renegade growers demand dedicated treatment); and the Sancerrois (encompassing Pouilly-Fumé and other nearby Sauvignon-dominated appellations). Along the way, I’ll touch on a few additional far-flung, isolated viticultural outposts. So, for example, this report on Muscadet sneaks in wines from two growers in the Vendée, a windswept sector along the Atlantic Coast one-third of the way from Nantes to Bordeaux.

This first group of annual Loire reports will be unusually copious in that I am focusing on two vintages, 2014 and 2015, as well as reviewing some wines from earlier growing seasons, primarily ones that have been released by their estates over the past two years or are due for release or re-release in 2017. I conducted my tastings in the course of July and August 2016 visits to 97 Loire estates as well as, via samples, from nearly another hundred producers, between September 2016 and March 2017. Taking Muscadet and the Nantais as my starting point offers an excellent opportunity to reinforce the importance of considering the Loire in pieces, since here vintage 2014 is superlative to a degree not equaled elsewhere along the Loire. This example also illustrates why I have chosen to offer four vintage charts for the Loire, each focused on a single grape variety. These charts, which will be extensively updated with the appearance of each new report, cover Muscadet, Cabernet Franc from the Central Loire, Central Loire Chenin Blanc and Sauvignon Blanc (as grown overwhelmingly in the Sancerrois and adjacent Touraine).

Two Excellent But Very Different Vintages

Vintage 2014 is one of the finest for Muscadet in living memory. And given the stylistic vision, quality consciousness and know-how that today characterize this genre’s foremost practitioners, it’s credible to claim that no previous vintage in the Nantais has boasted so many exciting wines. Like nearly all of Northern Europe, this region experienced a surprisingly wet, cool summer, August having been particularly unseasonable and unpropitious. But a balmy, breezy September turned the tide of mildew (or, in some instances, rot) and brought a small crop to unexpected ripeness.

What distinguished the Nantais from most of viticultural Northern Europe in 2014 was that an Atlantic high-pressure system extended the sunny, windy streak into October, whereas most other Loire growing regions had to contend with the return of at least sporadic rain. The sole downside for growers of Muscadet is that the aggregate concentration of aromatic components, sugar, extract and acidity in 2014 varied inversely with juice-to-skin ratio, which kept shrinking throughout this growing season’s critical late innings. So while their wines were sensational, growers remained troubled by how little there was to sell. (A similar ratio of quality to quantity prevailed in 2012, a Muscadet vintage whose best wines rival those of 2014.)

Their relative scarcity having been noted, a survey of the U.S. marketplace revealed continued, widespread availability of top Muscadets from vintage 2014. There are several reasons for consumers’ luck in this respect. First, quite a few American importers are faithful, longstanding supporters of the top Nantais growers and were thus rewarded with relatively good supplies despite low yields. (And among the fertile new wave of Franco-American importers focusing especially on “natural” wines are many who are receptive to the unique virtues and potential of wines from growers in this sector.) Second, for reasons I will explain below, the recent trend among growers of Muscadet has been to stagger releases over an ever-longer period, so that certain top 2014s will not reach the marketplace – and in some cases won’t even be legally allowed to – much before early 2017. Third, even many of the terrific basic bottlings from top growers remain in stock here and there, occasionally even at discounted prices, simply because the good news of their exceptional quality has failed to percolate through the wine-loving public, while in the meantime vintage 2015 enjoys an early, Europe-wide can’t-go-wrong reputation, whether or not deserved – and in many growing regions it isn’t.

Although there is a tendency even among some knowledgeable critics to think of Muscadet as a high-acid genre, the underlying chemical facts belie that misconception, which is just one of many reasons why comparisons with Chablis or dry Chenin and Riesling, frequent though they are, are usually misleading. That having been noted, vintage 2014’s relatively elevated acidity lends the wines an unprecedented combination of invigorating brightness, penetration and energy. These features are allied with ripe aromatics that encompass pit and citrus fruits as well as flowers. Moreover, the acidity is buffered by extract levels that one also perceives as density, alcoholic levity notwithstanding.

Vintage 2015 left most Nantais growers smiling, if less broadly than those in many other Northern European growing regions. While young vines and certain sites were stressed by summer heat and drought, abundant but not excessive late-summer rainfall restarted maturation in any malingering vines, and a generous crop could eventually be harvested relatively early. Waiting would have been problematic in many vineyards because, in the words of Domaine de l’Ecu’s Fred Niger, “it felt like Louisiana in September,” quite the opposite of the clear skies and breezy conditions that had prevailed in 2014. But results were universally superior to those in 2013, when the excessive autumn rain that followed a very dry summer had caught many conscientious growers on the cusp of picking a late-ripening crop.

Acid levels in 2015 are surprisingly ample, probably due as much as anything to the effects of vines having periodically shut down in mid-summer. The very best wines—those made from grapes whose aromatic evolution kept pace with advancing must weights—can hold their own against the 2014s; and enophiles who prioritize texture or are sensitive to high acidity may well prefer 2015. It’s not incorrect to state that the 2015s generally taste riper, but the meaning of “ripe” must be carefully parsed in the case of Muscadet, because this is a genre in which fruit flavors seldom predominate, although 2015s occasionally offer exotic or tropical fruit suggestions. I don’t doubt that the best of them will age gracefully, something that has proved true even of wines from the extremely hot, dry 2003. But as was the case with that latter vintage, handicapping the young 2015s for aging potential is tricky. I have accordingly been very conservative with my drinking windows.

Inimitable wines from ancient vines ... and undramatic landscapes. Here, the vines of pioneer Jo Landron’s Fief du Breil. (courtesy Damien Casten)

A Misunderstood Bargain

The Loire as a whole is surely France’s Bargain Garden, the source of countless distinctive, delicious, often ageworthy and genuinely complex wines that retail for between $10 and $25. But among those bargains, Muscadet is in a class by itself for sheer numbers, as well as for the subtle complexity and ageworthiness of the best examples. That this genre is well worth cellaring seems still not to have penetrated the consciousness of most wine lovers or even of many self-described experts. Received opinion still largely pegs Muscadet as a wine for drinking young and fresh – and there’s nothing wrong with that – especially with shellfish, a pairing recommendation of limited use in helping spread word of this wine category’s virtues, one of which is its sheer versatility at table. That Muscadet generally weighs in barely on one side or the other of 12% alcohol is conducive to levity and enhanced refreshment value, which in turn contribute significantly to the genre’s compatibility with a wide range of cuisine, not to mention its suitability for warm-weather outdoor enjoyment. The high levels of dissolved CO2 that result from sur lie bottling add an invigorating quality to the majority of Muscadets as well as enhance the stamina of open bottles by displacing air.

Discussions of Muscadet inevitably call to mind an even more familiar “M” word from the realm of wine, and one that’s regularly subjected to unnecessarily confusing equivocation. To be sure, many of the most prominent scents and flavors of Muscadet are best captured by mineral descriptors. At the same time, these wines are grown in a region whose soils are conspicuously dominated by eroded igneous and metamorphosed rocks, often with a glistening, glinting appearance and textural graininess. And it won’t come as a surprise except to wine novices that nearly every grower of Muscadet puts great stock in a belief that its organoleptic characteristics vary according to the type of rock in question, whether schist, granite, gneiss, orthogneiss, amphibolite, gabbro, flint or some mixture thereof. These rocks themselves get referred to routinely, albeit without conceptual clarity or scientific substantiation, as “mineral.”

But when you hear about minerals allegedly being conveyed to the wine and resulting in a “taste of granite” or “... of gneiss,” bear two things in mind. First, vines aren’t literally conveying minuscule traces of rock to your receptors, which probably couldn’t register their presence anyway. Second, if the aromatic, textural or flavor distinctions allegedly associated with a specific sort of geological underpinning elude you, know that you are in good company! While I can often sort by geologically distinct site the organoleptic characteristics of bottlings within any given grower’s portfolio, I find it challenging to identify common sensory characteristics among, say, granitic Muscadet from diverse growers and vineyards. I seem to recognize certain tendencies, but I certainly don’t experience the sort of clear-cut gustatory distinctions that I perceive between, say, Gamay grown in Beaujolais on eroded granite versus chalky clay, or Riesling grown on porphyry versus slate.

Méthode Ancienne? Across the Loire, growers are experimenting with earthenware vessels. Here, just a portion of Fred Niger’s extensive collection at Domaine de l’Ecu, a trailblazing Muscadet estate for four decades under Guy Bossard – and perhaps in future, too. (16th century choral music was playing to the young wines on the occasion of my most recent visit.)

The bargain that top-notch Muscadet represents unfortunately also points to a region-wide liability. This wine genre is so underappreciated that even a few of the best growers have difficulty turning a profit on its sale. A series of recent shortfalls due to frosts, hail, poor flowering and generally challenging weather have forced growers out of business at an accelerating rate. (Those in villages closest to Nantes can profitably turn their vineyards into residential property.) “There were 70 growers in Gorges when I started out in 1975,” related André-Michel Brégeon, “and today there are 20.” For the vast majority of regional producers, crop loads are left as large as appellation regulations and the conditions in any given growing season permit, and machine harvesting is an economic necessity. But the discreet charms of Muscadet easily morph into vapidity and thinness at high yields, and this category, like a white tablecloth, registers even tiny phenolic imperfections. That so many growers like those canvassed in this report strive idealistically for excellence against the headwinds of low esteem for their appellation – assiduously crop-thinning where necessary and hand-harvesting at least their best vineyards – represents almost miraculous good fortune for us consumers. No less amazing and fortunate is that young, inspired growers continue to take over family domains or even to start new ones, while regional veterans like Brégeon and Marc Ollivier have serendipitously found collaborators who will assume ownership and carry on a precious legacy.

Scrupulous, attentive viticulture and vinification are critical with Muscadet because it is essentially a naked wine. Low in fruity esters and alcoholic body let alone residual sugar, it needs to be naturally well-built and blemish-free to compensate for its lack of clothing or make-up. Attempts to raise it in small barrels have generally proven successful only if these are truly aged and flavor-neutral. Nuance and understatement aren’t drawbacks in Muscadet, but are instead among its virtues – though, to be sure, not ones that all enophiles will equally value. I wish I could say I’m shocked (though I am certainly incensed) that the INAO has just revised the basic Muscadet appellation to permit blending with up to 20% Colombard, Chardonnay or Sauvignon, a change with which the “... Sur Lie” appellations will hopefully not be threatened. (A majority of Nantais vignerons already grow supplemental cépages in order to bottle wines that will have varietal name recognition and obvious aromatic identity; but of some two dozen such wines I tasted in connection with this report, few merited published tasting notes.)

The Family of Muscadets

The vast majority of wines reviewed in this report carry the appellation Muscadet Sèvre et Maine Sur Lie, which applies to the largest, most important Nantais sub-region, south and east of Nantes, and to wines bottled off of their lees by November of the year following the harvest. Two growers in the Côtes de Grandlieu southwest of Nantes are also covered, and one in the Coteaux de la Loire, a spacious but sparsely farmed sector on either side of the Loire upstream from Nantes and north of the Sèvre et Maine. Wines from certain parts of the Nantais are labelled simply Muscadet or Muscadet Sur Lie without further geographical specificity, but wines from those sectors don’t turn up in the present coverage.

When you spot a wine in this report whose name does not include “Sur Lie,” that is seldom because the wine was racked or filtered first rather than having been bottled straight off its lees. Paradoxically, it is generally because the wine spent too long on its lees to qualify. Not granting late-bottled wines the “Sur Lie” appellation is in theory a means of protecting that designation for an especially fresh, lively style. Since the vast majority of Muscadet, including the best, is raised in enormous (typically glass- or tile-lined) underground concrete tanks, its evolution prior to bottling is slow, though gradually marked by loss of dissolved CO2, textural enrichment from lees contact and subtly enhanced complexity. Since the arrival of the new millennium, many quality-conscious growers have increasingly been giving their ostensibly best wines extended élevage, often naming these for the relevant village and or soil type—for instance, to pick a designation that acquired early prevalence, “Granite de Clisson".

Brought to the Nantais in the 17th century from Burgundy, where it all but disappeared, the Melon grape can channel the geologically diverse soils of Muscadet into consumate refreshment and intriguing but subtle complexity, provided yields, clusters and berries remain small, as here, looking almost Riesling-like, at Stéphane Orieux’s Domaine de la Bregeonnette. (courtesy Stéphane Orieux)

Understandably, this was also viewed as a potential tool for achieving higher prices and a decent profit margin. A few adventurous regional veterans and a significant share of newcomers, many of whom are influenced by the “natural wine” movement to vinify with low sulfur, are bottling some wines that routinely and intentionally undergo malolactic transformation, often in large casks or older barriques. Although the new-wave results are quite distinctive from the characteristics normally associated with Muscadet, many of these wines are distinctively delicious and probably ageworthy.

Permission was granted early in the new millennium for growers to collaborate in proposing specific “communal crus” (crus communaux) whose appellations would be subject to lower yield, longer élevage and higher must weight requirements than those that apply to Muscadet Sèvre et Maine Sur Lie, the precise criteria varying according to the commune in question. With vintage 2011, the first three cru appellations were granted, each associated with specific geological underpinnings: Le Pallet (gabbro), Clisson (granite) and Gorges (clay-rich Gabbro). Beginning with vintage 2014 we have Goulaine (schist), Mouzillon-Tillières (gabbro), Château-Thébaud (granite), and Monnières-Saint Fiacre (gneiss), while La Haye-Fouassière and Vallet are imminent, though I find hard to imagine how the latter’s geological diversity—incorporating gabbro, granite and schist—is to be reconciled with the INAO’s Procrustean template.

In anticipation of these new appellations, some growers began holding back wines that they might otherwise have bottled sooner. But it’s debatable whether, say, a wine that includes “Clisson” and “cru” as part of its official appellation will persuade consumers to pay more than they would have for one labeled “Granit du Clisson” and bearing in fine print the official appellation “Muscadet Sèvre et Maine.” A dubious aspect of communal cru appellations is that growers will likely be prohibited from identifying their wines by village unless the village in question qualifies as an official cru communale. (In Alsace, that restriction has already been onerously put into place.) And the category’s very name is misleading, in that multiple villages have generally been subsumed under the names of those that are best known. Each cru communale is, as already noted, expected to reflect specific geological underpinnings. But even Loire growers and other committed terroiristes do not pretend that rocks alone are destiny, and some of them opine that the aggregation of villages or hyphenated crus such as Monnières-Saint Fiacre and Mouzillon-Tillières are driven as much by commercial convenience as by respect for terroir. At least the law continues to permit Nantais growers to vineyard-designate their wines without being restricted to a list of approved sites (as growers are in Chablis, for instance, where only premier or grand cru vineyards may be mentioned on labels), but the future in that regard is also disturbingly uncertain.

A Wealth of Available Vintages

On top of the delayed, staggered release of cru or prospective cru Muscadets, quite a few estates harbor unsold bottle stocks that their importers are periodically permitted to tap, often at scant price premium. Whether this situation is a result of growers’ intentions or simple failure of even outstanding wines to sell out on initial release, the overall effect is that a wide range of vintages are currently reflected in the marketplace, and consequently also in this report. Readers should consult my soon to be updated vintage chart and are encouraged in particular to seek out some wines from the fascinating and impressive 2010 and 2012 vintages. And since my reports on Muscadet will always, for the just-mentioned reasons, include multiple vintages, I have taken the liberty of occasionally sneaking in recent tasting notes on older wines even if their re-release is not known to be pending. Hopefully, my having done so will encourage more wine lovers in the rewarding and eminently affordable habit of cellaring Muscadet.

Nor is the typical fermentative vessel of Muscadet any less prosaic than its landscapes. Here, Remi Branger, Marc Ollivier’s young partner at Domaine de la Pépière contemplates a 2004 cru freshly drawn from one of the region’s ubiquitous subterranean, glass-lined concrete tanks and destined for bottling at 24 months.

My coverage follows the usual Vinous conventions, including the use of point spreads in parentheses to designate wines tasted prior to bottling. Bear in mind that assessments of Muscadets tasted from subterranean cement tanks a year or more prior to bottling will be more reliable than assessments of many other sorts of wines made even as close as a few weeks before bottling. The reasons, which I have already adumbrated, are twofold. Since racking off the lees is generally intentionally avoided, and fermentation usually takes place in the same underground tanks where the wine will spend its entire pre-bottling life, there is no late “assemblage” to consider. Also, the post-fermentation evolution of wine in enormous glass-lined cement tanks is significant but typically quite subtle and relatively predictable. (Rare instances of malolactic transformation are an exception, but that usually takes place, if at all, within nine months of harvest.)

These factors having been noted, certain tasting notes might still prove ambiguous, since a grower might occasionally bottle two identically labeled batches separated by months or, exceptionally, even additional years in tank. A Muscadet-specific convention followed in my notes and grower introductions is to refer to Melon de Bourgogne simply as “Melon.” That’s not just to save time. No, believe it or not, this grape’s full name was recently deemed too likely to confuse consumers and offend Burgundian growers. It was therefore officially, albeit ludicrously, shortened to “Melon B.” and its growers admonished to refrain from spelling out the B-word.

You Might Also Enjoy

Austria’s 2015 Rieslings and Grüner Veltliners: Ripe and Ready, David Schildknecht, February 2017

2014 on the Mosel: Man Bats Last, David Schildknecht, November 2016

2014 Mosel: A Hard But Often Rewarding Harvest, David Schildknecht, October 2016

Show all the wines (sorted by score)

- André-Michel Brégeon

- Beauregard

- Belle Vue

- Bonnet-Huteau

- Bregeonnette

- Bruno Cormerais

- Chereau-Carré

- Complemen'Terre

- Eric Chevalier (Domaine de l'Aujardière)

- Fay d’Homme

- Fruitière

- Grand Mouton

- Haut Bourg

- Haute Févrie/Claude Branger

- Haut-Planty

- Julien Braud

- Landron (Domaine de la Louvetrie)

- L' Ecu

- Michel Delhommeau

- Pepière

- Pierre Guindon

- Pierre Luneau-Papin (Pierre de La Grange)

- Prieuré La Chaume

- Saint-Nicolas

- Veronique Günther-Chéreau