Browse using the new Vinous website now. Launch →

Printed by, and for the sole use of . All rights reserved © 2015 Vinous Media

Argentina New Releases: Cool Times in the Desert

BY STEPHEN TANZER | JULY 6, 2017

Within just the last six weeks I’ve experienced global warming up close and personal: 92-degree late-May weather in Burgundy, 102 degrees in Walla Walla before the end of June, and the steam heat of a New York City summer. But somehow Mendoza, Argentina’s engine of wine production, a semi-arid desert region that could not produce wine without irrigation from melting Andes snow, has not had a classically warm, dry growing season since 2012 – until this year, that is.

Following a string of average to cool years culminating – or should I say bottoming out – with the extremely difficult El Niño harvest of 2016, the 2017 growing season witnessed warm to hot conditions in summer, slightly higher than average rainfall, and reasonably cool weather in March and April. The crop was very small, partly due to losses to spring frost. Cooler temperatures and drying breezes after the humid spells enabled the fruit to remain healthy and early indications are that this vintage will produce very concentrated wines, whites as well as reds, with considerable aromatic complexity and freshness. It’s early days of course but some producers are already calling 2017 one of Argentina’s finest vintages of the past 20 years.

Vineyards in Mendoza. Photo: By Wines of Argentina

Fresher Vintages and More Vibrant Wines

Still, it’s clear to me that cooler and less parched conditions are conducive to making more aromatically complex wines at somewhat lower octane levels. Argentina’s best growers and winemakers have gained a great deal of experience in recent years at getting their fruit ripe (but not overripe) under cooler conditions. Their grapes have benefited from longer hang time and somewhat better retention of natural acidity. The succession of cooler years from 2013 through 2016 has meant, at least at the level of serious producers, better-balanced wines than ever before, and, in the case of single-site bottlings, a growing number of wines that display distinctive terroir character.

The Italian enologist Alberto Antonini, who is partner/winemaker for the Altos Las Hormigas venture and serves as consulting winemaker at several other wineries (in addition to consulting in Chile, Europe, the U.S., Australia, South Africa and elsewhere), told me that following four years that featured more rain and higher humidity than usual in Mendoza, “I don’t have the same feeling of being in a desert that I had when I started working here in 1995.” But he also believes that “these new weather conditions” are making Mendoza a much more interesting place, overall, for grape-growing. “I see more biodiversity in the environment and the flavors are becoming more interesting and complex. I’m not surprised by this as most of the world’s greatest wines do not come from desert-like conditions but from more humid places.”

Cooler and more humid conditions are not the only reason that recent vintages have yielded a lower percentage of wines with roasted- or dried-fruit character than ever before. Producers small and large are planting vineyards at ever-higher altitudes and cooler exposures – particularly in Mendoza – including sites that were previously believed to be incapable of ripening grapes consistently. This search for higher and cooler sites is a pattern that has characterized many winegrowing areas around the world and that has only been reinforced by global warming.

A high-altitude vineyard in Cafayate. Photo: By Wines of Argentina

Concrete Improvements in Élevage

Meanwhile, improvements in vinification and élevage are also resulting in fresher, more refined wines. For example, many producers in Argentina have cut back on their use of (potentially oxidative) new oak, especially with the fruit from young vines, and the result has been wines that showcase their unique site characteristics more convincingly. At the same time, the use of new, small concrete tanks and “eggs” is on the increase, resulting in more complex, layered white wines and rosés and purer, more delineated reds with no loss of freshness.

Concrete containers are hardly new to Argentina, notes Trapiche’s chief winemaker Daniel Pi, who reminded me that the use of concrete vats for both white and red wines was common practice in Argentina until the 1990s. Thereafter, most of these containers were replaced by stainless steel, which offers a polished surface that is easy to clean and is ideal for fermentation with commercial yeasts (and often with just a single strain). In the previous generation’s concrete containers, potassium bitartrate sediment routinely accumulated, making what Pi described as “a thin and rough carpet that allowed various micro-organisms to nestle there.” But today’s higher-quality concrete cubes and eggs can more safely be used for spontaneous fermentations, thanks in part to a host of viticultural improvements made in recent years, including better sanitary conditions in the vines and more careful harvesting, which produces much healthier grapes and grape skins. Pi added that he now ferments many of his reds in classic square-shaped concrete vats coated with epoxy food-grade liner, which gives a smoother surface that can be kept almost as clean as stainless steel. He is also increasingly using concrete eggs for micro-vinifications of experimental plots.

In fact in recent years some top producers have replaced a percentage of their stainless steel tanks (and in some cases their barrels or larger casks) with concrete eggs, which provide more thermal insulation and thus result in smoother – and frequently longer – fermentations. Most winemakers who use concrete eggs also maintain that the shape of these containers and the cooler temperature at the top of these small-volume receptacles (they typically hold the equivalent of three standard barrels of wine) result in steady movement of the lees, thus allowing for a gentle, non-mechanical batonnage without the introduction of oxygen. This method yields wines with more pliancy and texture – especially constructive for many white wines – and with little loss of freshness.

Head Catena Zapata winemaker Alejandro Vigil, who also makes wines under his own El Enemigo label, is particularly enamored of concrete tanks for his white wines and rosés, citing the beneficial effect of “a continuous bâtonnage.” (I should note that Daniel Pi says he has never seen this effect and refers to it as “an urban myth.”) Vigil also uses concrete eggs for a percentage of his reds, particularly in place of stainless steel. “Where there is a need for greater oxygenation, the porosity of the concrete decreases reduction,” he explained.

The Challenging 2016 Growing Season

Although many producers are putting an optimistic face on the 2016 vintage, my own tastings to date suggest that this El Niño year was the weakest for the vast Mendoza region in a long time, perhaps since 1998, another El Niño year plagued by copious rainfall and unusually cool weather. It was difficult in terms of quantity as well, as the total crop in Mendoza was off 39% from 2015 levels (although much of this shortfall occurred in eastern Mendoza, which is better known for its bulk wines than for high quality). A very cool and rainy spring pushed the flowering back to a month later than average and the summer continued cool and wet; growers who don’t normally need to do more than a couple of vineyard treatments during the growing season had to do eight or more, owing to issues with mildew (powdery as well as downy) and botrytis. Making matters worse, the key month of April for this late harvest was plagued by as much as 400 millimeters of rain in parts of Mendoza, making the harvest an adventure and speeding the spread of rot.

Catena Zapata’s Adrianna Vineyard. Photo: By Catena Zapata

Poorer, quick-draining soils in Uco Valley were frequently spared the worst effects of the rainfall (although Roberto de la Mota, who makes the Mendel wines and others, told me that rainfall of 736 millimeters between budbreak and harvest was about three times the average), but many growers in Luján de Cuyo had already irrigated their vineyards before the season began, so some of these wines can show an element of dilution. (The average annual rainfall in Mendoza is typically around 200 millimeters per year, but the vines need as much as 700 for proper balance over the course of the year, and this shortfall is made up by flood irrigation using melted snow from the Andes mountains.)

Most 2016 reds from Mendoza lack their normal body and ripeness; many are downright skinny and green. Constant treatments against rot in the vineyards were essential, as was strict selection at harvest-time or more labor-intensive harvesting in multiple passes. But even this vintage has its bright spots. Well-drained, high-altitude vineyards were best able to handle the copious rainfall, and rot was less likely to take hold in well-aerated sites. Some good red wines were made, albeit with less depth, concentration and structure than wines from most recent years. (I should add that de la Mota was not the only winemaker who noted that summer temperatures in 2016 were actually warmer than those in the last disastrous El Niño year, 1998.) And I also tasted some delicate yet vibrant white wines that clearly benefitted from the cooler conditions—and earlier harvesting.

As a general rule, the 2016s, reds as well as whites, are lower in alcohol than they usually are, and in many cases this is a good thing. But lower, warmer, less-breezy sites on the eastern side of Mendoza were often disaster areas in 2016, with rot spreading quickly and most growers having to harvest their fruit before it fully ripened. Some growers even abandoned their vineyards, as the low prices they receive for their grapes could not justify the necessary investments in vineyard treatments and precise harvesting. Here only the strictest possible selection enabled some producers to make passable wines but often there was no usable fruit at all.

The flow of El Niño air was centered over Mendoza. Salta far to the north and Patagonia to the south suffered much less from El Niño rainfall. Moreover, both of these regions had experienced sharp losses from spring frost and thus were more likely to have been able to bring their smaller crop loads to adequate ripeness, even under cooler-than-average conditions.

Vineyards in San Juan. Photo: By Wines of Argentina

Other Recent Vintages

Last year I wrote that 2015 was the most difficult vintage in years for Mendoza, but it nonetheless offered better conditions than 2016. The growing season in Mendoza was plagued by atypically cool temperatures and potentially damaging rains. Heavy rain in early April was especially hard on the later-ripening Cabernets. Two thousand fourteen was also a taxing year for growers, with substantial rains in February followed by warmer but humid conditions in March. In both of these vintages, many growers chose to harvest early, fearing incipient rot and still more rainfall. But it must be pointed out that rot pressures were far milder at higher altitudes and on well-drained sandy alluvial, rocky or gravelly slopes, and that those who succeeded largely credited long hang time for producing sufficiently ripe wines at moderate alcohol levels. (And, as in 2016, Patagonia and Cafayate Valley in Salta had drier conditions in ’15 and ’14 than did Mendoza.)

For more detail on the 2015 and 2014 vintages, as well as a brief recap of the cool, dry and often outstanding 2013 season, please refer to my coverage of Argentina on Vinous last year.

A Three-Tier Market

Argentina wine production continues to be a two-tiered market—although perhaps three-tiered would be a better description. At the top level, there’s a steadily growing number of stunning and increasingly soil-specific high-end wines coming from favored sites and soils. Some truly world-class wines retail for as little as $30 or $40 but prices for a handful of bottlings can soar to $100 or more – and in some cases much more.

At the opposite end of the spectrum, Argentina also produces a vast number of essentially interchangeable and often dull red wines that fall short on concentration, fruit ripeness or tannin management, or display clear flaws (and this category does not even include the vast amount of bulk wine made in Argentina). These bottles are of little or no interest to serious wine lovers, no matter what their prices. But between these two extremes is a steadily expanding and often compelling middle category of well-made, sufficiently concentrated and characterful wines that offer outstanding value in the $15 to $25 range. (In this price range, only Spain, southern France and Chile can compete for sheer volume of offerings).

Colomé's Altura Maxima bottling comes from the highest vineyard in the world, at 10,200 feet. Photo: By Hess Family Wine Estates

What To Look for on the Label, Even If It's Not There

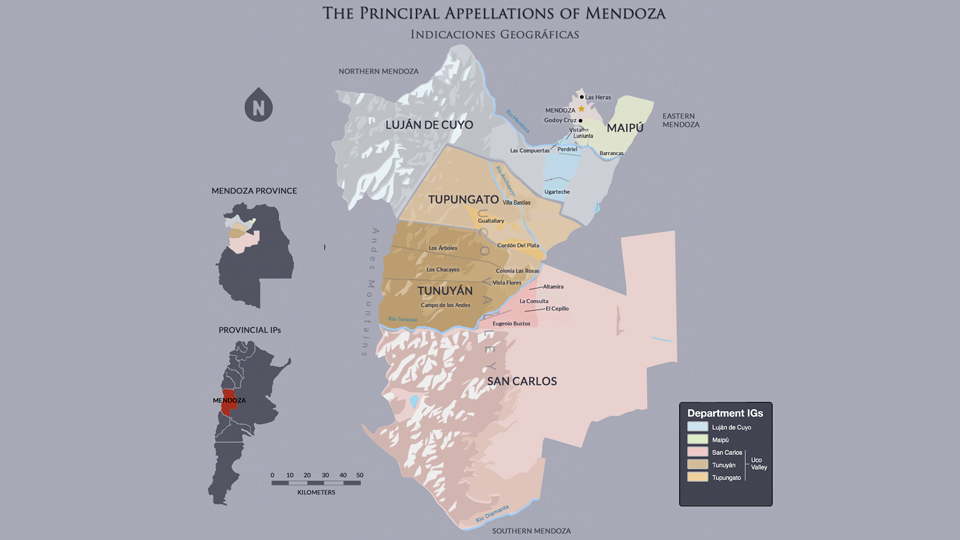

Complicating the consumer’s challenge of finding good wines is the fact that Argentina’s – and especially Mendoza’s – appellation system is still confusing and inconsistent. As long-time aficionados of these wines know, Argentina's first D.O.C, Luján de Cuyo, established in 1993, has always been considered a prized region for Malbec. (Luján de Cuyo, which comprises roughly as much vineyard acreage as Napa Valley, includes the sub-appellations Vistalba, Las Compuertas, Perdriel, Agrelo, Major Drummond, Chacras de Coria, Carrodilla, Tres Esquinas and Ugarteche and is considered a departmental IG [Indicación Geográfica, or recognized geographical area]). Mendoza includes four other departmental IGs: Maipù, San Carlos, Tunuyán and Tupungato. The last three are all part of the greater Uco Valley, which has become a hotbed of vineyard discovery and wine production since the turn of the new century, particularly its sites on chalky soils at higher altitude. Just since 2005, wine production in the Uco Valley has grown by nearly 80%, and new plantings are going in at altitudes that now exceed 5,000 feet above sea level.

Today, much of the excitement in Mendoza is focused on two new areas that many insiders now refer to informally as Argentina’s first grand crus. Gualtallary, in a rocky part of Tupungato with vineyards planted as high as 5,300 feet, benefits from particularly cool conditions, including lower daytime high temperatures during the peak of summer, and poor soil with a strong element of calcium carbonate. The wines produced from these vineyards often strike me as somewhat Burgundian in their pungent chalky, salty minerality, their energy and wildness, and their impression of intensity without undue weight. The better examples give every indication of considerable ageability. Gualtallary produces outstanding Malbec but it’s also a top source for Cabernet Franc, Chardonnay and even Pinot Noir. Catena Zapata makes many of its top bottlings from its holdings in Gualtallary, while the Michelini brothers have also helped to spread the Gualtallary gospel via a host of distinctly vibrant and typically lower-alcohol wines from numerous varieties and under several labels, including Zorzal, SuperUco, Passionate Wine, Altar Uco and Michelini Wine.

The other of Mendoza’s “grand crus” is Paraje Altamira, which lies in the alluvial cone of the Tunuyán river in San Carlos, in the southern part of the Uco Valley. It, too, now has its own IG owing to its distinctive and complex soils. Like Gualtallary, Paraje Altamira features some calcaire but the soil is heavier here and the wines are typically rounder and more elegant. But the calcium carbonate in both of these areas gives the wines vitality and tension—Alberto Antonini used the word “voltage.”

Courtesy of Catena Institute of Wine

Unfortunately, highly specific place names do not necessarily appear on the front labels (or even back labels) of Argentine wines, so consumers with limited experience with Argentine wines often have no way of knowing where the fruit is sourced. Complicating matters is the fact that some widely recognized IGs are actually trademarks owned by a single wine company, and thus cannot yet be legally used by third parties. For example, recognized IGs such as Perdriel and Vistalba are in the hands of Norton and Bodega Vistalba, respectively. A large wine company owned by an ex-politician trademarked the name Gualtallary and currently an association of growers in Gualtallary is attempting to negotiate the right to use this name on their labels. (In fact, these growers are also trying to convince the INV – Instituto Nacional de Vitivinicultura – that there are really five distinct areas within Gualtallary, all of which, they feel, deserve their own names.) Incidentally, Paraje Altamira was invented as the name for the IG as Altamira was already the name of a winery, but Gualtallary is not yet a legal IG, owing to the trademark issue.

To cite just one extreme example of how confusing labels can be, Gualtallary is located within Tupungato, which in turn is part of Uco Valley. And Uco Valley lies within greater Mendoza. Any of these four place names may appear on front labels, where experienced wine drinkers typically expect to find a wine’s appellation.

Similarly, numerous IGs have been granted in recent years for vineyard areas in Salta, Patagonia, San Juan and La Rioja that have proven their specific attributes, but only a few of these place names carry much meaning for wine drinkers in Argentina’s export markets. Some notable exceptions are Cafayate in Salta (the latter name actually owned by Etchart, who allows other wineries to use the name on their labels) and Rio Negro and Neuquén in Patagonia.

I have tried to include highly specific place names in the data base wherever possible, even though in some cases these names may not appear on the label. But note that a majority of Argentine wines are still blends from two or more sites, sometimes located far apart. If the fruit comes, for example, from two vineyards within Uco Valley, the producer is entitled to use the appellation Uco Valley. But if a wine is made from vines in Uco Valley and Luján de Cuyo, it can only use the broader Mendoza appellation. There are even some wines labeled simply Argentina, as they come from two or more different provinces—for example, Mendoza and Salta.

I tasted the wines in this article in New York City in April, May and June.

You Might Also Enjoy

Vertical Tasting of the Nicolás Catena Zapata 1997-2012, Stephen Tanzer, October 2016

Argentina: The Cool Years, Stephen Tanzer, March 2016

Argentina: New Releases, Stephen Tanzer, February 2015

Show all the wines (sorted by score)

- Abremundos

- Achaval Ferrer

- Alamos

- Alba en los Andes

- Alma Austral

- Alma Negra

- Alpamanta Estate

- Alpasión

- Altaland

- Altar Uco

- Alta Vista

- Altocedro/Karim Mussi Winemakers

- Altos Las Hormigas

- Amalia

- Andeluna Cellars

- Angulo Innocenti

- Anko

- Antonio Mas

- Antucura

- Barbarians

- Belasco de Baquedano

- Benegas

- BenMarco

- Bodega Aleanna

- Bodega Amalaya

- Bodega Argento

- Bodega Bressia

- Bodega Calle

- Bodega Catena Zapata

- Bodega Chacra

- Bodega Cruzat

- Bodega Del Desierto

- Bodega del Fin del Mundo

- Bodega Del Rio Elorza

- Bodega del Tupun

- Bodega Graffigna

- Bodega Iaccarini

- Bodega La Rural

- Bodega Malma

- Bodega Noemia

- Bodega Norton

- Bodega Poesia

- Bodega Renacer

- Bodega Rolland

- Bodegas Bianchi

- Bodegas Caro

- Bodegas Fabre

- Bodegas Salentein

- Bodega Teho

- Bodega Vistalba

- Bodini

- Casa de Uco

- Casa Montes

- Casarena

- Casir dos Santos

- Casta del Sur

- Cepas Elegidas

- Chakana

- Chaman

- Cheval des Andes

- Clos de los Siete

- Colle di Boasi

- Colomé

- Corazón del Sol

- Corvus

- Crios

- Cuarto Dominio

- Cuvelier Los Andes

- Dante Robino

- De Angeles

- DiamAndes

- Domaine Bousquet

- Doña Paula

- Don Cristobal

- Dos Puentes

- Durigutti Family Winemakers

- El Esteco

- El Porvenir de Cafayate

- Ernesto Catena Vineyards

- Escala Humana Wines

- Escorihuela Gascón

- Estancia Mendoza

- Etchart

- Familia Cassone

- Familia Schroeder

- Finca Agostino

- Finca Ambrosía

- Finca Decero

- Finca el Origen

- Finca Las Moras

- Finca Sophenia

- Fincas Patagonicas

- Flechas de los Andes

- Gauchezco

- Gen del Alma

- Gouguenheim

- Graffito

- Grupo Foster Lorca

- Hacienda del Plata

- Hermanos

- Huarpe

- Huentala Wines

- Humberto Canale

- Kaiken

- Krontiras

- La Celia

- Lagarde

- La Luz

- Lamadrid Estate Wines

- La Posta

- Los Clop

- Los Toneles

- Luca Wines

- Luigi Bosca

- Lui Wines

- Luminis

- Maal Wines

- Manos Negras

- Marcelo Pelleriti Wines

- Marchiori & Barraud

- Mascota Vineyards

- Masi Tupungato

- Matervini

- Matias Riccitelli

- Melipal

- Mendel

- Michelini Wine

- Monte Quieto

- Monteviejo

- Mythic Estate

- Navarro Correas

- Nieto Senetiner

- Pasarisa

- Pascual Toso

- Passionate Wine

- Piatelli Vineyards

- Piedra Negra

- Proemio Wines

- Pulenta Estate

- Puramun

- Reginato

- Revolver

- Riglos

- RJ Viñedos

- Ruca Malen

- Septima

- SoloContigo

- SonVida

- Sottano

- Spielmann Estates

- SuperUco

- Susana Balbo

- Terrazas de los Andes

- Tiano & Nareno

- Tikal

- Tilia

- TintoNegro

- Tomero

- Trapiche

- Tres 14

- Trivento

- Vaglio

- Ver Sacrum

- Via Revolucionaria

- Vicentin Family Wines

- Viña Alicia

- Viña Cobos

- Viña Las Perdices

- Vinilo

- Vinorum

- Vinos de Potrero

- Vinyes Ocults

- XumeK

- Zorzal Wines

- Zuccardi