Browse using the new Vinous website now. Launch →

Printed by, and for the sole use of . All rights reserved © 2015 Vinous Media

South Africa’s Ongoing Wine Revolution

When South Africa emerged from nearly a half century of apartheid in the early 1990s, its wine producers stepped up to the international plate with two strikes against them. Twenty-plus years later, they have dug themselves out of their early hole and prospered.

The Bad Old Days

Depending on how you look at it, South Africa is either the oldest New World wine region or the newest Old World area. The Cape region’s first wines were produced by the Dutch East India Company in 1659 and many of the area’s most famous wine estates were making wine by the early 1700s. But following the phylloxera epidemic in the late 19th century many of the Cape’s vineyards were replanted with high-yielding varieties like Cinsault. A huge wine glut ensued.

Then, during the dark decades of apartheid, the wine industry suffered from sanctions that kept their wines out of the U.S. and many other important export markets. South Africa’s wine farms had little incentive to produce wines that could compete in a global setting. In fact, most of the country's grape growers simply sold their fruit to co-ops, who turned it into either distilled alcohol or sherry and port. Its winemakers, who rarely traveled internationally, were out of touch with new developments in the world of wine.

Moreover, the Cape’s producers had trouble even getting the raw materials needed to bottle real wine—basic materials such as high-quality farming equipment, corks and even bottles. More important, the country’s vines were generally beset with viruses, and local nurseries were in no position to remedy the situation because they did not have easy access to clean stock from abroad. Vineyards literally had to be replanted every 15 to 20 years, so the stock of old vines in the most commercially important regions like Stellenbosch and Constantia was very low.

South Africa, despite its great head start at making wine, had virtually fallen off the world’s wine map. And with the end of apartheid and the lifting of sanctions in 1991, the U.S. market was suddenly flooded with mostly low-end and decidedly mediocre wine from South Africa.

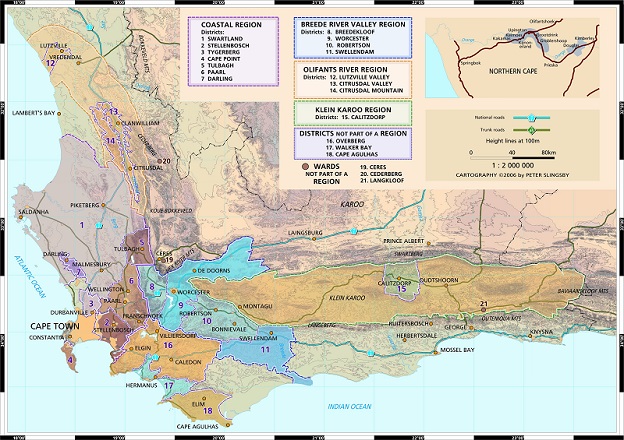

Map of South Africa's wine regions (click for high resolution version). Courtesy of Peter Slingsby/Wines of South Africa

But That Was Then And This Is Now

I previously toured the Cape’s most important wine-producing regions in 2002, 2004 and 2006. And since ’06, I have regularly tasted and reported on new releases in depth. But there’s no substitute for being on the ground, in the dirt, in a wine region, and I was overdue for a visit. In an action-packed week in April of this year, I learned firsthand how quickly and profoundly the local wine landscape has changed. If, for whatever reason, you haven’t dipped into South African wines lately, I urge you to reconsider this very rich and varied wine culture, where prices are extremely reasonable.

For starters, widespread replanting of virused wines and grafting over new vines onto virus-free rootstock have made a huge difference in wine quality since the turn of this century. Growers are now able to produce more consistently ripe fruit that’s less likely to show the intensely herbaceous or tea-like flavors, not to mention the offputting notes of creosote and burnt rubber, that previously marred many of the Cape’s wines. A new and much younger generation of winemakers has traveled the world and understands what it takes to compete in international markets. And they are far less restrained by tradition than their parents and grandparents were.

Whereas historically the most important producing regions dating back centuries were Stellenbosch and Constantia, many of the most exciting wines in recent years have come from “new” regions. In most cases those new regions are in cooler areas—closer to the influence of the sea, at higher altitude, more open to cooling breezes. Nowadays, even wealthy, long-established vineyard owners in Stellenbosch seeking to expand their production are increasingly looking to cooler regions like Elgin, Walker Bay and Elim to the south, and to Darling to the north, for growth, with the specific objective of making fresher, more energetic wines with lower alcohol than their original home vineyards could provide.

Wines aging in Eben Sadie’s cellar

The Swartland Revolution

And then there is the exciting Swartland, which has introduced a whole new dimension to Cape wines. This vast hot, dry region north of Cape Town was traditionally the Cape’s breadbasket, with wheat and other grains extensively planted. As far as wine was concerned, Swartland was long known for producing rustic, high-alcohol wines suitable only for blending—if that. The region was dominated by co-ops that survived by making outsized reds, off-dry whites and base wine for brandy. But visionaries like Charles Back (Spice Route) and Eben Sadie, and more recently others like Adi Badenhorst, Andrea and Chris Mullineux, Marc Kent, Callie Louw, Donovan Rall and David Sadie quickly saw the potential in this area—particularly its extensive stock of old hillside vines—to make great wine. Best of all, land was cheap, offering an obvious avenue to success for talented young winemakers who wanted to strike out on their own.

By the way, all of the above producers, plus others, are members of the Swartland Independent Producers (SIP) association, which requires that their wines be “naturally produced” and aged in no more than 25% new European oak. I think of the SIP as the vinous equivalent of Denmark’s Dogma film movement, only less dogmatic and more accepting of winemakers’ personal tastes.

Revealingly, four important international grapes that had previously been widely planted in Swartland—Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Chardonnay and Sauvignon Blanc—are now virtually banned from the region’s new wines: technically they can constitute no more than 10% of a blend. Meanwhile, the permitted grapes are mostly Mediterranean and Rhone Varieties that are much better suited to the region’s climate and soils. Red varieties like Carignan, Cinsault, Grenache, Mourvedre, Pinotage, Syrah and Tinta Barocca and whites like Chenin Blanc, Marsanne, Roussanne and Viognier must represent at least 90% of all blends.

Some of the most exciting wines I tasted in South Africa in April were made in Swartland, or were vinified elsewhere from Swartland fruit. And they are a far cry from what you might expect from a hot, parched area. Thanks to dry-farming, very old low-yielding vines and earlier harvesting to retain aromatic freshness, growers are able to make remarkably complex and scented wines at surprisingly moderate alcohol levels. Temperatures during the summer here average a full 5 degrees Centigrade higher than those in Paarl, for example, and yet the best wines I tasted from the Swartland are remarkable for their aromatic perfume, complexity, flavor definition and elegance. I happened to look at a printout of technical information on the 60 or so wines I tasted from the top producers during a day in Swartland in April and was shocked to see that only one of them reached as high as 14% alcohol. Among the other regions whose wines I tasted extensively, only Elgin showed alcohol levels as moderate as Swartland’s.

Adi Badenhorst with his old bush Grenache vines in the Raaigras vineyard in Swartland

No Superstar, But A Well-Rounded Team

South Africa has long been penalized in the international wine market for not having a signature brand—like Malbec in Argentina, or Sauvignon Blanc in New Zealand or Pinot Noir in Oregon. If the Cape region can be said to have one or two signature grapes, they would probably be Chenin Blanc (often called Steen here), which is still the most heavily planted variety in the Cape and was historically a base wine for brandy production, and the distinctive red variety called Pinotage, a love-it-or-hate it hybrid of Cinsault and Pinot Noir that was developed in the 1920s by the University of Stellenbosch. (Before that time, Cinsault was the dominant red grape in the Cape.) Neither has attracted an international following, although the vibrant, racy, food-friendly versions of Chenin Blanc being made today deserve broader attention.

If the Cape wine industry does not benefit from a transcendent superstar grape, it fields a deep team of varieties, with a talented bench waiting to come into play. On my recent tour, I tasted outstanding wines from varieties like Chardonnay, Sauvignon Blanc, Chenin Blanc, Roussanne, Viognier, Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Franc, Syrah (often called Shiraz in South Africa), Grenache, and Pinot Noir for starters—plus a few more I rarely encountered eight years ago. But perhaps even more exciting were the dozens of new and often creative blends, not just the old standby red and white Bordeaux blends, but complex combinations of red and white Rhone Valley and Mediterranean varieties. Many of the best of these wines, needless to say, are coming from Swartland, where the region’s producers are given to experimentation, not to mention planting offbeat varieties like Portuguese red grapes, Tannat, Barbera, Durif, Assyrtiko, Palomino and others.

So the Cape wine scene is remarkably dynamic and constantly evolving. A lot of South Africa’s most exciting wineries did not exist before the mid-1990s. Although countless talented young winemakers cut their teeth with established wineries, in South Africa or abroad, they embarked on their own projects with little baggage, thanks in part to the relatively low cost of grapes and, in some areas, vineyards.

The view from Tokara, facing Delaire

White Wines Cannot Be Denied

I should point out that about half of South Africa’s wine production is white—not unlike production in Washington State’s high desert. But where upwards of 80% of Washington’s finest bottles are red, in South Africa good white wines are ubiquitous. After all, this is a Mediterranean climate, not a desert, and conditions are conducive, especially in cooler regions and microclimates, to producing whites with energy and personality, beginning but not ending with many fine Chardonnays, Sauvignon Blancs and Chenin Blancs. In fact, white wines represent a sizable percentage of the highest-scoring wines in this article. For consumers who, like me, have concluded that it’s harder to find seriously good white wines at a moderate price than reds, South Africa offers a wealth of choices.

The view from Fairview farm

Eno-Tourism On The Rise

There’s no better way to discover South Africa’s wines than to discover them in South Africa. Eno-tourism has surged in recent years, led mostly by the region’s beautiful wine farms. The Cape area—and of course Cape Town itself—is a gorgeous place to visit (Stellenbosch is especially spectacular), with a moderate climate conducive to touring, as most of its rain falls during the winter months. Thanks to the weak South African currency, hotel prices are usually moderate and eating and drinking at restaurants can be remarkably cheap. Many of the Cape region’s finest restaurants are located at wine estates like Jordan, Klein Constantia, Tokara and Delaire Graff. They tend to offer outstanding selections of the local wines, and wine prices generally offer amazing value for visitors with strong currencies.

Brush fire burning at Vergelegen in April

A Brief Look At Recent Vintages

It was all over but the smoke when I arrived in April, following the extremely early 2015 growing season. The year was very hot and very dry and very early, with many wineries beginning the harvest in mid-January. Drought conditions and wind triggered many serious brush fires in February, including a very damaging one on Table Mountain in Cape Town itself, and fires were still a problem during my tour in mid-April, long after the harvest had ended. Even so, many producers seemed optimistic about wine quality in 2015, as the best fruit had been picked during a compressed harvest before the fires became widespread. Some producers already believe 2015 will be the Cape’s best vintage since 2009.

Two thousand fourteen was a challenging, cool year that began with a wet spring and was also plagued by harvest-time rains. The season brought a large crop, but fruit that was sufficiently ripe could produce nicely concentrated, lighter wines, including some very fresh whites. Problems of rot were widespread later in the harvest. The best window for harvesting was February, and this warm, dry month appears to have favored the white varieties as more rains fell in March.

Two thousand thirteen featured a very large, late crop that ripened well under favorable conditions without extremes and yielded many very satisfying reds and whites, with alcohol levels mostly moderate. During an unusually warm, dry December, the normally late varieties partly caught up with the early ones, with the result that the harvest eventually took place over a shorter-than-normal period. This vintage is widely viewed as classic, if not outstanding.

Two thousand twelve was a mostly moderate growing season with a hot, dry January that produced reasonably fleshy wines, many of them with great immediate appeal. The harvest period was cool, dry and relatively relaxing for growers, producing red wines with excellent color and flavor intensity at moderate alcohol levels. Many of the producers I visited in April love these wines for their balance and upfront appeal, even if most of the wines do not have the structure of the best vintages. Big reds from 2012 may be an ideal place for you to begin your adventure with these wines, as they are rarely austere or overly tannic.

Two thousand eleven was a very uneven growing season that began with a cold, rainy flowering but also saw extended drought and heat in January and February, which sapped a lot of wines of natural acidity and resulted in rather tropical flavors in many whites. Many wineries struggled to manage their irrigation water, while in some areas, periods of humidity triggered rot. The 2011 harvest was generally early and rushed, with many varieties ripening simultaneously. In the key Stellenbosch area, wines from Bordeaux varieties are often high in alcohol and relatively low in acidity, due to warmer-than-usual nights during the weeks prior to the harvest. But varieties that are often plagued by greenness tended to do well, as the warm summer weather burned off much of the pyrazines (the compounds responsible for green pepper and green bean elements in many wines, especially those from red Bordeaux grapes).

The 2010 growing season

was also a roller-coaster. An irregular budburst was followed by very cool

October and November weather that delayed vine development. Windy

conditions affected potential crop levels at the flowering, by sizable

percentages in some areas. As it was difficult to get into the wet vineyards to

spray in November, many growers battled downy mildew through December. Then

favorable summer conditions and the generally small size of the crop allowed

for ripening to begin catching up. There were some heat spells during the

summer, including a sharp spike during the first week of March, and the summer

was characterized by unrelenting winds, with sunburn further reducing the

potential size of the crop and some wineries running out of irrigation

water. Most of the fruit ripened, helped by looser bunches and smaller

berries, and cooler weather during the very early days of the harvest helped

white grapes retain good flavor intensity. White grapes picked later

tended to make flatter wines.

Two thousand nine is widely considered to be South Africa’s most recent outstanding vintage: a late year that began with excellent water reserves in the soil and remained cool and wet into January, slowing down ripening but ultimately leading to greater flavor intensity. The weather then turned very dry and heat arrived during the second half of February, ripening the crop in a hurry. Some wineries reported that they started picking two weeks later than average yet finished a month earlier. The 2009s have impressed me with their aromatic complexity, density and depth of material and ripe tannins. The best of them are wonderfully complete and satisfying wines, well worth seeking out. But with the late heat, there are also some warm or blurry wines.

Keep in mind that vintage comments for the vast Cape region are generalizations; you’ll find many more specific comments by winemakers in the course of this article.

Boekenhoutskloof’s vineyards, against the Franschhoek mountains

A Note About Fynbos

The Western Cape is known for its extraordinary biodiversity (there are reportedly more plant species in Table Mountain National Park than there are in the entire United Kingdom). Of the roughly 8,500 plant species found in the region, the majority are native fynbos vegetation, the shrubs and bushes that blanket the area’s coastal plains, valleys and mountains. In a region that sees little precipitation during the summer months, the normal vegetation is shrubland rather than grasses. I think of fynbos as South Africa’s version of the garrigue of Mediterranean France. Although markedly different in character, elements of fynbos—botanical and medicinal herbs, dried spices and the like—can be found in many South African wines.

All of the wines in this article were either tasted in South Africa in April or subsequently in New York. In many instances the wines I tasted in South Africa will not arrive in the U.S. market until later this year. Please note that I plan to post notes on several additional sets of wines from top-quality producers over the next few weeks, as additional samples arrive through the importers.

You Might Also Enjoy

Vertical Tasting of Sadie Family Wines Columella, Stephen Tanzer, January 2015

--Stephen Tanzer

Show all the wines (sorted by score)

- Alheit Vineyards

- Allée Bleue

- Anthonij Rupert Wines

- Anwilka

- Ashbourne

- Badenhorst Family Wines

- Bartinney

- Beaumont Family Wines

- Bellingham

- Beyerskloof

- Blaauwklippen Vineyards

- Black Pearl Vineyards

- BLANKBottle

- Boekenhoutskloof

- Boschendal

- Bouchard Finlayson

- Braai

- Buitenverwachting

- Cape Point Vineyards

- Catherine Marshall Wines

- Cederberg

- Chamonix

- Cirrus Wine Company

- Colmant

- Constantia Glen

- Creation Wines

- Crystallum

- David & Nadia

- Delaire Graff

- Delheim Estate

- DeMorgenzon

- De Toren

- De Trafford Wines

- De Wetshof Estate

- Diemersdal Wine Estate

- Diemersfontein

- Distell

- Dombeya Wines

- Dornier Wines

- Dorrance

- Downes Family Vineyards

- Eagles' Nest

- Edgebaston

- Ernie Els Wines

- Etienne Le Riche

- Excelsior Estate

- Fable Mountain Vineyards

- Fairview

- Flagstone

- Franschhoek Cellars

- Glen Carlou

- Glenelly Estate

- Graham Beck Wines

- Groot Constantia

- Groote Post Vineyards

- Guardian Peak

- Hamilton Russell Vineyards

- Hartenberg Estate

- Haskell Vineyards

- Indaba

- Iona Vineyards

- Jam Jar

- Jardin (Jordan Wine Estate)

- Joostenberg Wines

- Julien Schaal

- Kaapzicht

- Keermont Vineyards

- Ken Forrester Wines

- Klein Constantia Estate

- Künstler

- La Motte

- Lanzerac

- La Vierge

- Lismore Estate Vineyards

- Lomond Estates

- Lourensford

- Luddite

- MAN Family Wines

- Meerlust

- Meinert

- Miles Mossop

- Morgenster

- Mount Abora

- Mulderbosch Vineyards

- Mullineux

- Muratie

- Mvemve Raats

- Nederburg

- Neethlingshof Estate

- Neil Ellis

- Newton Johnson

- Oak Valley

- Painted Wolf

- Paul Cluver Estate Wines

- Plaisir de Merle

- Porseleinberg

- Post House Vineyards

- Raats Family Wines

- Rall Wines

- Reyneke Wines

- Rickety Bridge

- Ridgeback Wines

- Rudi Schultz Wines

- Rupert and Rothschild

- Rustenberg Wines

- Rust en Vrede Estate

- Sadie Family Wines

- Savage Wines

- Scali

- Sijnn

- Simonsig

- Southern Right

- Spice Route Wine Company

- Springfield Estate

- Stark-Condé

- Steenberg

- Stony Brook

- Tamboerskloof

- Teddy Hall

- Thelema Mountain Vineyards

- The Winery of Good Hope

- Tierhoek

- Tokara

- Tormentoso (MAN Vintners)

- Vergelegen

- Vilafonté

- Vuurberg

- Warwick Estate

- Wildekrans

- Yardstick Wines

- Zevenwacht