Browse using the new Vinous website now. Launch →

Printed by, and for the sole use of . All rights reserved © 2015 Vinous Media

Day by Day: South Africa in 2025

BY NEAL MARTIN | OCTOBER 2, 2025

Day One: Arrival, Showers, Cabernet Franc

South Africa’s opening act never alters. Mountains painted in watercolours on the horizon gracefully flaunt their magnitude. Glance right and life crossfades into the harsh reality of the township that laps against the carriageway, a rusting reminder of the inequality that rivens this part of the world. Like previous years, Ronnie is behind the wheel, and updates how he has batted away life’s curveballs since we last met. With visits crammed into every waking hour, I prefer not to make a wrong turn in a place where wrong turns can have consequences. Better to have someone navigating safely from A to B so that my mind is focused on wine, even if his Hyundai was never designed for axle-crunching driveways or potholes that could sink a battleship. Upon arrival at “base camp”—the Oude Werf hotel, nested in the historic whitewashed heart of Stellenbosch—the receptionist apologises that my room is not ready. I phone winemaker Bruwer Raats and ask if I could use their shower. A towel is ready upon my arrival. Lathered and clean, I switch to tasting mode.

I effectively hit the ground running as Raats and his cousin Gavin Bruwer Slabbert guide me through their portfolio. Raats is the paradigm of a Cape winemaker. He is a straight-talking, amiable bear of a man, hard-working and entrepreneurial. Raats’ name has become synonymous with Cabernet Franc, a variety that debuted as a blend with the 1980 Rubicon from Meerlust (incidentally included in this report), then returned eight years later as a standalone variety at Warwick Estate. Clearly it thrives in Stellenbosch, arguably more attuned to the vicissitudes of the growing season than kingpin Cabernet Sauvignon. “In warm areas, you plant Franc on a cool slope, and in cool areas, on a warm slope so that it can ripen before the heatwaves and avoid a spike in sugar,” Raats advises. “The biggest mistake is to plant Cabernet Franc in fertile soils that yield excessive growth, which is why low-potential, well-drained granite soils are ideal. Clonal material has improved over the last two decades, such as 623, 327 and the best one, 214. These clones do well with 110 and 101-14 rootstocks. People use more whole bunch because they have learned, firstly, how to obtain physiologically ripe stems, and secondly, that Cabernet Franc does not need a lot of new oak.”

Mirroring the trend in Right Bank Bordeaux, Cabernet Franc has become another bow in Stellenbosch’s quiver. That said, it is a fickle variety. It is less obedient, more mercurial. There is a sweet spot where it translates tropes of spiciness or pepperiness without transgressing into vegetal traits that can appear if there is dissonance between phenolic and physiological ripeness. Raats’ affinity towards Cabernet Franc is attested by the quality of his wines, which are ridiculously good values. For the first of many times, I wonder if there is a typo in the price list.

Really? Is that all? For wine that good?

Raats’ and Bruwer’s offshoot project, Bruwer Vintners Vine Exploration, has a wider remit and embraces a broader array of varieties sourced from single sites. That said, there is no Grenache Blanc in 2025. Workers strolling past the vineyard reached out and ate the fruit. Who can blame them for reaching for free food when people eat to live, not vice versa?

Slabbert apologises and leaves early. His son has a crucial rugby match, and here, rugby is the religion, like American Football without the shoulder pads and inexplicable time-outs. Since both winemakers are rugby fanatics, we discuss the huge match against Australia this coming weekend. Everything will stop for 80 minutes while 30 men chase an oddly shaped ball that cannot bounce properly. If rugby were a grape variety, it would be Cabernet Franc.

Day Two: Blinkers, Stuck Bakkie, Biodynamics

Jonkershoek Valley is a short drive from the hotel. Streets that throng with students give way to barren mountainsides draped in fynbos, interpolated with vines that in this parish include the plot of Chenin Blanc planted in 1905, the source of Eben Sadie’s celebrated Mev. Kirsten. Surveying the yawning valley full of flora and fauna, it is easy to see how the Cape hosts triple the biodiversity of the entirety of Europe. The panorama transfixes during my first tasting at Stark-Condé, its tasting room pitched Japanese-style on stilts in the middle of an idyllic lake. Mental note: next time I will bring blinkers to prevent any distraction.

The view from the tasting room at Stark-Condé in the Jonkershoek Valley.

Next is Rustenberg, with owner Murray Barlow. We jump into his bakkie—Afrikaans for the 4x4 trucks necessary to drive around estates—to see the layout of his vines and meet the free-roaming cattle that keep cover crops under control. My video is ruined by a bull that “fertilises” the vineyard on cue. There are some things Vinous readers don’t have to see. Afterwards, a trip to the so-called “Wendy House” at DeMorgenzon, the mansion perched on a hilltop where indefatigable proprietor Wendy Appelbaum resides. It was her idea to pipe classical music into the vineyard. How that affects the vines, I do not know. Unlike corn, grapevines do not have ears. But hey, biodynamic winemakers proselytise burying cow horns filled with the same substance accidentally filmed at Rustenberg. Is that any less bizarre?

That leads me neatly to my next visit, next door at Reyneke, where the Hyundai gets stuck in the muddy driveway. Owner Johan Reyneke fetches a rope to tow us out, and the Hyundai silently complains. Reyneke is a poster child for biodynamics in the Cape. Steiner’s tenets do not automatically render any wine superior, but undeniably, these wines exude such personality that you cannot help falling for their charms. (Check out this video explaining Reyneke’s viticulture and vineyard landscaping.)

Finally, I continue to the peripatetic Ken Forrester. Forrester is overseas at the time of my visit, which gives me time with winemaker Shawn Mathyse, one of the few black winemakers who, through sheer talent and commitment, holds important positions within major wineries. Ethnic diversity in South Africa is a subject I have touched upon in past reports. It is crucial for the long-term future of the wine industry to avoid being traduced as a luxury beverage that is made for and consumed by a white minority. Wine is for everyone. There is a long way to go, but thanks to various initiatives, not least the protégé program run by the Cape Winemakers Guild, things are inching in the right direction.

Day Three: South Coasters, Slobbering Dogs and Cetacean No-Show

After my requisite bowl of granola (I aver that a hotel is best judged by the quality of its cereal), Ronnie is waiting outside, ready to drive to the coastal town of Hermanus. My first tasting is with a small collective known as the “Cape South Coasters,” mostly young and budding winemakers with relatively small portfolios, connected by a single-site/low-intervention ethos.

Assembled winemakers under the Cape South Coasters banner. I had just been informed of my daughter’s successful A-level results, hence the cheers.

The venue is Thamnus Wines, out in the middle of a desolate nowhere. There is a frontier-like vibe, pushing the viticultural boundary eastwards along the South Coast, where there are pockets of virgin land with potential for making exceptional wine. Vineyards with limited potential are in retreat, now being turned into more profitable orchards, which explains why acreage is the lowest it’s been since 1997. Rather than a general shrinkage, like in Bordeaux and elsewhere, these regions are witnessing the shrinkage of substandard viticultural areas, which is inevitable if global demand continues falling. Still, with that context in mind, you feel what’s possible in this remote part around Cape Agulhas and its hinterland, where there are 2,646 hectares under vine.

From there, I head to Hemel-en-Aarde, or “Cape Côte d’Or,” the cradle for Pinot Noir and Chardonnay. Dutch settlers baptised this valley “heaven on earth” for obvious reasons. Anthony Hamilton Russell’s gigantic dogs slobber greetings over my jeans that accrete canine paw prints and odours throughout my trip. Dogs sniffing my trousers on the final day could bark my entire itinerary. Fearing that these “Hounds of the Baskervilles” are eyeing him as lunch, Ronnie locks himself in the Hyundai. As is customary, I taste the wines from Berene Sauls, who started her career as a bushy-tailed employee at Hamilton Russell. Sauls’ journey to winery owner as a descendant of freed slaves is inspiring, aside from the fact that her latest vintages have the audacity to surpass some of her mentors. Her impromptu rap is one of the highlights of my trip. A woman of hidden talents.

I wend my way through most of the growers in Hemel-en-Aarde. Creation is packed with tourists soaking up the views, wines and food at their ever-popular restaurant. Oeno-tourism has become increasingly important here as more wineries exploit their natural backdrop. For some, as much as 40% of sales can come directly from visits, obviating the obstacles surrounding exports. Nothing seals the bond between consumer and wine like visiting a vineyard. Thinking of Bordeaux’s travails, some châteaux should take a leaf out of the books of Creation, Tokara and Jordan inter alia and welcome wine lovers with open arms. Give them reason to visit an estate beyond mere tasting.

Well, can you spot a whale in Hermanus Bay?

In the evening, I walk down to the quayside overlooking Hermanus Bay. In recent days, whales have been leaping practically in formation. I wait patiently for the cetacean show. I just stare at waves for half an hour. That’s 30 minutes of my life I will never get back. Finally, a splendid fish supper at Fisherman’s Cottage, with a quartet of mid-1980s South African wines that are poleaxed by inferior corks, crumbling at the mere sight of a corkscrew.

Day Four: Devious Primates, Bot River, Eyebrows

Up bright and early to continue tasting in Hemel-en-Aarde. My first port of call is with winemaker Hannes Storm. His wines can pass as Burgundy. Indeed, of all the regions I have covered outside the Côte d’Or, the wines of Hemel-en-Aarde have the most similitude to their lodestar. All they lack are the prohibitive asking prices. Despite the distance, Storm is a Burgundy habitué and divulges that he will make his maiden Clos de Vougeot this autumn. At least you do not have to worry about baboons in Clos de Vougeot. Storm tells me that the devious primates learned to untie protective netting and helped themselves to fruit, leaving the rest for grateful birds. The Cape’s biodiversity has its drawbacks.

Craig Wessels at Restless River inspects his Pinot Noir vines, his workers pruning whilst the vines are dormant.

Next, a short drive to Restless River, where Craig Wessels loads me into his bakkie for a tour of his vineyard that includes recalcitrant rows of Cabernet Sauvignon. The Cape’s “anything goes” mindset gives rise to the panoply of varieties across the region and underwrites its stylistic eclecticism. In France, Wessels would be prohibited unless he wanted to forsake appellation status, even after identifying an anomalous outcrop of granite subsoil that invites Cabernet instead of Pinot Noir. Plant what tastes best. Wessels’ pursuit of Cabernet raised a few eyebrows. The calibre of his Main Road & Dignity cuvée lowered them.

We depart for Bot River, another fast-improving region, for another welcome multi-producer tasting that means less travelling, more tasting. These are some of the Cape’s best growers—John Seccombe (Thorne & Daughters), Marelise Nieman (Momento) and Peter-Allen Finlayson (Crystallum and Gabrielskloof). Finlayson has sacrificed the annual “Vintners Surf Classic” to attend this tasting, not that I sympathise. I have been invited, but a) I cannot surf, and b) I fear sharks like Ronnie fears big dogs.

Finally, my first visit to Benguela Cove in Walker Bay, a vast estate owned by Penny Streeter OBE, whose rags-to-riches backstory is worth reading. The wines, overseen by ex-KWV winemaker Johann Fourie, are a little more on the commercial side, but not without a couple that pique my interest. The evening is spent at a well-regarded seafood restaurant with a couple of winemakers who have their own side-projects, of which there are countless dappled over the Cape. Some of those small acorns can grow into tall trees.

Sadie. Alheit. Raats…They were acorns once.

Day Five: Elgin, Connie? Fat Butcher I, 38-22

A precondition when my South African itinerary was organised was ParkRun on Saturday morning, the weekly communal five-kilometre jog. You must look after yourself in this line of work. Conveniently, this one is around Benguela Cove. Having boasted his prowess as a champion sprinter, I coerced Ronnie to join, harbouring images of “Chariots of Fire” and Vangelis’s theme tune. This does not come to pass. In fact, I never spot him crossing the finish line. He promises that he came 67th. When I check the results, 67th place was a 60- to 65-year-old woman named Connie.

My time is slow: 30 minutes 25 seconds. But I did slow to a canter to admire a statuesque heron, wings outstretched as if to say, “How’s that for a wingspan.”

As usual, I work through the weekend. These are often my busiest days. Following a superb tasting at Damascene in Elgin with Jean Smit—plus a quick tour of his vines, including parcels planted on stakes (échalas in France), as is becoming increasingly popular—I call in at Richard Kershaw, the English-born Master of Wine and Nik’s half-cousin. What this guy does not know about clones, nobody knows, not even the clones themselves, though thankfully in the Cape, people do not obsess over them. Clones are still important, not least because the prevalence of leafroll virus means that massal selection is fraught with risk. As one winemaker remarked, you would have to be so stringent in choosing what cuttings to propagate that you might as well buy a virus-free clone.

Richard Kershaw and his moggy.

Kershaw’s portfolio can be a bit of a mouthful with its various cartographic references; however, his Chardonnay, Pinot Noir and Syrah are sublime, channelling the nuances of their respective terroirs with elan. No surprise that after returning, I served his Chardonnay blind to a couple of Burgundy die-hards duped into thinking it was top-notch Saint-Aubin. I love Burgundy, yet when tasting exemplary wines from the likes of Kershaw and Smit, I mull upon how they are shunned by so many cognoscenti who are convinced that the Côte d’Or is the be-all and end-all—too often, assumptions based upon price.

Returning to Stellenbosch, I taste with winemaker Bernhard Bredell. Bredell’s wines under the label Scions of Sinai have rapidly become sought-after, part of a movement that has invigorated Stellenbosch, dragged it away from the clichéd, cumbersome Bordeaux blends of old. One topic of conversation is the growing recognition of sub-regionality. He sent me a useful map.

This map shows various locations of hills—contoured wellsprings of quality advantaged by favourable terroirs in terms of altitude, orientation and soil type. Here, you can see how this region is exposed to the maritime influence of False Bay to the south, and especially to wind that helps moderate temperatures and improve ventilation. Duncan Savage believes that wind speeds have increased in recent years. Though that counters the spread of rot, it poses its own problems, not least in a vintage like 2023/24 when flowering was acutely disturbed and potential yields could be halved. Stronger winds are encouraging the échalas plantings like those I inspected at Damascene, which provide greater stability than trellised vines.

Note on the map how Stellenbosch is surrounded by mountains. One aspect that can only be appreciated first-hand is that, though winegrowing regions cluster in the southwest corner of the Cape, most are separated by mountains. This can predicate disparate growing seasons, much more than, say, Pauillac and Saint-Julien, or Gevrey-Chambertin and Morey-St-Denis. Case in point: the 2022/23 growing season. Many regions along the coast saw heavy rainfall that coincided with picking in mid-February, thus dividing those that managed to pick their reds before the heavens opened and those that did not. Or the September storms in Hemel-en-Aarde that caused infrastructure damage and huge mudslides that still scar mountainsides in Franschhoek. Shimmy north and Swartland was relatively untouched. After that, 2023/24 suffered uneven flowering, then a warmer, drier summer that particularly dried out more granitic soils, leading to smaller berries. Factor in the tapestry of ancient soil types that have degraded for up to 800 million years and you’ll understand why we are only beginning to understand South Africa’s panoply of terroirs and microclimates.

Bernhard Bredell is another rugby fanatic. Frankly, I am surprised that he joins me for dinner at one of Stellenbosch’s best restaurants, The Fat Butcher. The crucial Australia v. South Africa match is underway. But Bredell wants to share a 1990 Grand-Puy-Lacoste with someone who knows a bit about Bordeaux. Will Bredell’s Cabernets age as well as this Pauillac? I am certain they will. Who knows, perhaps in years to come they will be just as highly prized. South Africa’s Cabernet blends are now born with greater finesse, balance, poise and terroir expression, destined to evolve instead of just survive, more attuned to current predilections.

Bredell asks a nearby diner how the match is going. The diner tells him not to worry because the Springboks are coasting with 22 points to Australia’s zero. Bredell can now settle and enjoy the evening…

South Africa ends up losing 38-22.

The capitulation unites a nation in its soul-searching.

Day Six: “Discoveries,” Fat Butcher II, Tariffs

Sunday? A day of rest? Not on your nelly. Today I have an important all-day “Discovery Tasting.” That title is misleading because I am already familiar with the wines; I just do not have time to see everyone. This tasting includes serious wines from Vilafonté, Kanonkop and Lourens. One bottle from Quoin Rock staggers with the sheer weight of stickers, like one of those people addicted to tattooing their entire body, except here you might say the addiction is domestic competitions. Australian-born Mick Craven drops by with his latest releases, the only winemaker not lamenting last night’s result. One of the cadres of low-intervention winemakers, Craven now eschews oak barrels entirely and raises his wines in concrete vat. The shift away from traditional Bordeaux oak barrels to foudres and concrete so as to moderate oak influence has fundamentally altered the style of South African wine, a sea-change for those who associate the country with turbo-charged, alcoholic wines. These wines still exist. They have their place. But they now feel like an anachronism.

The evening is spent back at the Fat Butcher to compensate for missing out last year. My dining compatriot is one of the organisers of May’s Ten Years On tasting, now the head buyer at a major importer and able to make key buying decisions. This has been one reason that countries like the U.K. have really embraced South African wines. By contrast, the three-tier system in the U.S. means producers are reliant on salespeople to promote South Africa, and the wines often languish on the back pages of distributors’ brochures. The most successful producers invest time in the States, though that is often untenable due to cost, time and visa restrictions. Tariffs threw a spanner in the works just when South African wines began making inroads. Some U.S. importers compel producers to carry the burden of 30% import duties or risk being knocked off their books, whilst more benevolent importers absorb additional charges. A majority have agreed to share the cost, many fast-forwarding shipments before tariffs came into effect, though that may still alter the suggested final prices. The main risk is to by-the-glass wines, where South Africa’s cost-effectiveness has been driving demand. Perhaps higher prices will have the reverse effect? Maybe that will entice more to try South African wine because, historically, many claim that connoisseurs are put off by low prices. Sounds bizarre, but that is the world we live in.

Day Seven: The Breakfast Club, Franschhoek, Merry-Go-Round

Whilst most people are tucking into their granola at the Oude Werf at 7.30, or perchance, a cosy lie-in under the duvet, yours truly is swilling wine ‘round his mouth with Lukas van Loggerenberg and his pet moustache. The veil of sleep soon evaporates, simply because his wines elicit curlicues of euphoria, testing my ability to keep my infamous—and, according to a couple of winemakers, terrifying—poker face. Van Loggerenberg has become a top-division winemaker over the last two or three years, joining the elite band of Sadie, Savage et al.—remarkable since his maiden vintage was barely a decade ago, plus he does not own vineyards. It is meticulous sourcing and instinctive winemaking using rudimentary facilities that gave rise to his stupendous 2024s, which reach their zenith with a sensational pure Cabernet Franc, his “Breton” cuvée. Just a pity that he lost up to half his crop in places, due to what he calls “the windiest season [he] can remember.” Van Loggerenberg joins me for a quick espresso before Ronnie taps his watch and his Hyundai gallops off to another great Stellenbosch winemaker, Reenen Borman at Boschkloof Wines.

I also return to Anthonij Rupert, a completely different kettle of fish. This Franschhoek estate is owned by one of the wealthiest families in Africa. Reflecting on the difference between Anthonij Rupert and Van Loggerenberg, it is fascinating how the Cape is such a gallimaufry of personalities. One minute you are shaking hands with a billionaire whose winery is long-established. Next minute, someone straight out of college, the opening pages of fulfilling their dream, perhaps lent temporary space in a winery, profiting from praxis and near constant dissemination of know-how. That ethos helped transform an industry from a government-run monopoly to a shapeshifting ecosystem whose lifeblood is the innumerable exchanges of fruit between landowners and winemakers. Like Burgundy but without the secrecy, prime vineyards are frequently divvied up between growers, fruit shared or exchanged, undergirded by altruism and cooperation rarely seen in other wine regions where one-upmanship rules.

One theme from this year’s visit is the apparent “merry-go-round” of winemakers. Names become synonymous with wineries. However, if they are neither owner nor shareholder, then the likelihood is that at some point they move on. This can feel like the end of an era and induce hand-wringing. How often do you hear, “So-and-so has left, and obviously the wine has gone downhill”? The highest profile move pertains to my next visit.

Porseleinberg has been run with such independence since its inception that many believe it to be a standalone entity rather than part of Franschhoek-based Boekenhoutskloof. The latter is where I taste Porseleinberg, for the first time with Winemaker Gottfried Mocke instead of Callie Louw. Louw was offered a chance to build a vineyard from scratch on a nearby farm (see Producer Profile), which means that he will have to purchase fruit until his vines mature. Louw is one of several notable moves. Kiara Scott, whose wines lit up previous reports, has left Brookdale to join Hazendal. Eben Sadie’s son, Xander has replaced Scott at Brookdale, whilst Shanice du Preez, a protégé who worked with Duncan Savage, has stepped up as assistant winemaker. I heard of others, though they were not officially announced. Such a chain reaction of personnel changes can be positive. It staves off inertia, foments new ideas and thinking, foregrounds the next chapter.

Day Eight: Spirited Away, Breedekloof, ‘68 GS

Unless I spend a whole month in the Cape, it is impossible to visit everywhere, but it is important to me to keep upcoming regions like Breedekloof on my radar. Reminiscent of the tunnel in the opening of Japanese anime “Spirited Away,” a road tunnel is the portal to this hidden wine region. Breedekloof seems walled in by vertiginous mountains, the boulder-strewn moonscape even wilder than the rest of the Cape.

No idea what the collective noun for Breedekloof winemakers might be. Elizma Visser seated at right.

Like the last couple of years, Breedekloof winemakers have gathered for a group tasting, this time at Opstal’s winery, their camaraderie audible as my laptop whirrs into action. There is definitely an uptick in quality from the likes of Belle Rebelle, Daschbosch and Opstal, though it is Olifantsberg’s white Rhône blend, the 2022 Soul of the Mountain The Matriarch, that proves both the region’s potential and winemaker Elizma Visser’s talent. We return over the mountain pass where baboons patrol the roadside and pilfer food from slow-moving trucks. Such intelligent creatures, though a potential pest for winemakers. French winemakers complain about wild boar. Imagine if those boar were ten times as intelligent with nimble fingers.

Somehow, this makes me think of Stanley Kubrick’s “2001: A Space Odyssey.”

Further visits in the afternoon include Natte Valleij and David Finlayson. The latter opens a bottle of 1968 GS Cabernet Sauvignon, a Holy Grail, alongside its 1966 counterpart. I will detail this bottle in a Cellar Favorite, but suffice it to say that South African wines from the 1950s and 1960s have become highly coveted, with prices that would make Burgundy blush. Parallel to many European wine regions, this era predates the overuse of chemicals and herbicides, an era when winemakers unwittingly oversaw future icons. Much like Burgundy, that golden period tailed off in the 1970s, and even by the 1990s, quality paled against what it is today. This upswing means that South African wines should be compared to their European counterparts. This evening, I tutor a Chardonnay and Pinot Noir dinner where domestic wines are pitted blind against Burgundy. Both acquit themselves well, gems on both sides. As I expected, the wines from the likes of Storm and Restless River show as well as those from Henri Boillot and Dominique Lafon. Of course, market prices are not factored into the equation, but if they were…

Day Nine: Mini Savalanche, Durbanville Hills

No trip to South Africa would be complete without a visit to Constantia, in the foothills of Tabletop Mountain. I spend a couple of hours with the ever-chipper Matt Day at Klein Constantia for a retrospective of back vintages. The tasting not only includes their famed sweet Vin de Constance, but iterations of Sauvignon Blanc from specific sites. Day adores the variety, and has since working as an intern in the Loire at Pascal Jolivet. In the Cape, the variety is popular amongst consumers, if less so with critics and connoisseurs. I have never been convinced of the nobility or longevity of Sauvignon Blanc vis-à-vis Chardonnay or Chenin Blanc, but undeniably one or two of Klein Constantia’s aged Sauvignons have evolved well.

The Sauvignon Blanc theme continues with my inaugural foray into Durbanville Hills, just north of Cape Town. Another group tasting, this time at De Grendel, a historic estate founded in 1720 when it covered a vast swathe of what is now prime Cape Town real estate. From its highest point, one can easily see how these vines are exposed to the Atlantic. Low fronts barreling inland from the ocean can alter the weather in the blink of an eye. Sauvignon Blanc is the main variety here and, for reasons said, perhaps underlies why Durbanville Hills is less recognised than other districts. Still, a couple of wines from Groot Phesantekraal alert me to the variety’s potential.

Day Ten: Swartland, Taxidermists’ Paradise, Eglise d’Eben

Today is all Swartland, just over an hour’s drive from Stellenbosch. First port of call is Roundstone Estate to see Chris and Andrea Mullineux, next to a never-ending field of strawberries whose plastic canopy blights the landscape, as they annoyingly do around the Cape. The Hyundai protests as Ronnie tackles speed bumps built so high that they could stop a herd of buffalo. This is an extensive tasting through the Mullineux and Leeu Passant portfolios in Swartland and Franschhoek, respectively. Andrea Mullineux is an erudite winemaker. Throw her any subject on wine and she will return with detailed exposition and enlightenment. Mullineux’s wines have been fine-tuned in recent years and show more nuance, especially when juxtaposing the Iron, Schist and Granite cuvées. Of course, their Straw Wine and perpetual solera, the Olerasay, are stunning. The Cape is a dab hand at this sweet wine malarkey—just a shame that the style is so out of vogue, as any beleaguered Sauternais will tell you.

Next, the inimitable Adi Badenhorst. I cannot convey his Kalmoesfontein homestead-cum-winery-cum-artist studio in words. Imagine a commune with strangers wandering in and out, every nook and cranny populated by stuffed birds and marsupials. Shelves heave with paraphernalia, forgotten bits ‘n bobs, the detritus of intertwining lives brought together by their circus-master.

Adi Badenhorst in an outtake of Hitchcock’s “The Birds.”

There is an endearing undercurrent of chaos such that even Badenhorst is not sure what is going on. Behind his mien as a hilarious, outspoken and self-effacing winemaker lies a shrewd operator whose diversification into sherries was astute, ditto his ubiquitous Secateurs entry-level label and his acquisition with Eben Sadie of the neighbouring 200-hectare Rotsvas farm. Badenhorst has thus become an important source for some of South Africa’s most lauded labels, fostering that aforementioned collaborative ecosystem. Whereas in Burgundy, it seems commonplace for unscrupulous farmers to leverage their position and maximise selling price irrespective of fruit quality, Badenhorst’s altruism means that winemakers with limited means can apply their talent to top-grade fruit. Who benefits? Everyone. Badenhorst has slightly reined in some of his more outré cuvées and slimmed down his portfolio, which is better than ever.

On the balcony of Eben Sadie’s recently completed winery. No stuffed birds…yet.

Henceforth, I shall visit Eben Sadie and Badenhorst after each other because, proximity aside, whilst they share a similar ethos, aesthetically they are comically diametric. Over consecutive visits, Sadie’s Xanadu has risen. From inspecting the foundations when the air was thick with wet cement to its final unveiling, Sadie has overseen every detail with all the stress that entails. The winery stands as a testament to his achievements. It is grand in scale yet without frills, the décor is minimalist, the interior a reflection of the winemaker’s Zen-like demeanour. It is so calm that I search for a pulpit. Indeed, discussing wine with Sadie is like listening to a sermon, one infinitely more interesting than those I listened to every Sunday morning. In addition, Sadie has two new “babies” to add to his Old Vine Series that I outline in the Producer Profile and notes. Readers can also look forward to a Columella vertical coming to your favourite wine publication soon.

From here, I undertake another joint tasting at Kloovenberg with several winemakers, including Donovan Rall and David Sadie. I mention the previous weekend’s loss to Australia. The rugby-mad winemakers, who make most people feel vertically challenged, embark on a deep analysis of why the Springboks lost. Feigning expertise, I nod along. My rugby knowledge extends little beyond a) passing the ball backwards, and b) you will get hurt even more than in surfing.

Day Eleven: Mohicans, Duncan & Sam, Sole Survivor

Another day with a crack-of-dawn tasting at the hotel. Then off to Jordan, one of Stellenbosch’s premier estates. Gary Jordan has been an important player on the South African scene over many years, though like Badenhorst, he has diversified his interests after founding Mouse Hall Distillery and Winery in West Sussex. Jordan studied geology, so his passion leans towards viticulture more than winemaking, driven by marrying rock with vine. He planted the Cape’s mother block of Assyrtiko, a signature Greek variety that has caught the eye of many winemakers who view it as a viable alternative to Chardonnay or Chenin Blanc. Several producers now take cuttings, so get used to pronouncing/spelling Assyrtiko because you are likely to see more of it.

Winemaker Sjaak Nelson, sporting a trademark Mohican haircut and looking like someone you would be foolish to rugby tackle, suggests tasting at his home, which lies yonder on the estate. I don my metaphorical blinkers as the silhouette of Table Mountain woos me on the horizon, though I am equally transfixed by Nelson’s vintage reel-to-reel that pipes Cuban music during our tasting (though to reiterate for any winemakers with funny ideas, no extra points, even if you have impeccable taste). We bump into Jordan on the bumpy ride back, and it does not take long before he is enthusing about his new plantings and their importance in coping with climate change. At least here in South Africa, free from French appellation controllée rules, growers can adapt to global warming and plant varieties to safeguard the future instead of planting when it might be too late.

Winemaker Sjaak Nelson with proprietor Gary Jordan at the higher reaches of his Stellenbosch estate.

From there to Delaire Graff. As you might expect from an estate owned by the world-famous jeweller, it drips with luxury, including five-star lodges, spa and an obligatory Japanese restaurant. The winery itself is much more functional, without the “toys” that often adorn and distract those with limitless budgets. With Capensis virtually next door and South African-owned Tokara opposite, Delaire Graff is part of a tenderloin of luxury estates on the Helshoogte Pass that links Stellenbosch and Franschhoek. Graff and Capensis (also De Toren) fit into the mould of wines with a Californian slant and prices more in line with that state. That does not infer the wines are inferior, though in my experience, they rarely push the envelope. Instead, the wines are meticulously fashioned by domestic winemakers with one eye on an American audience. There is nothing wrong with that. Quite the opposite.

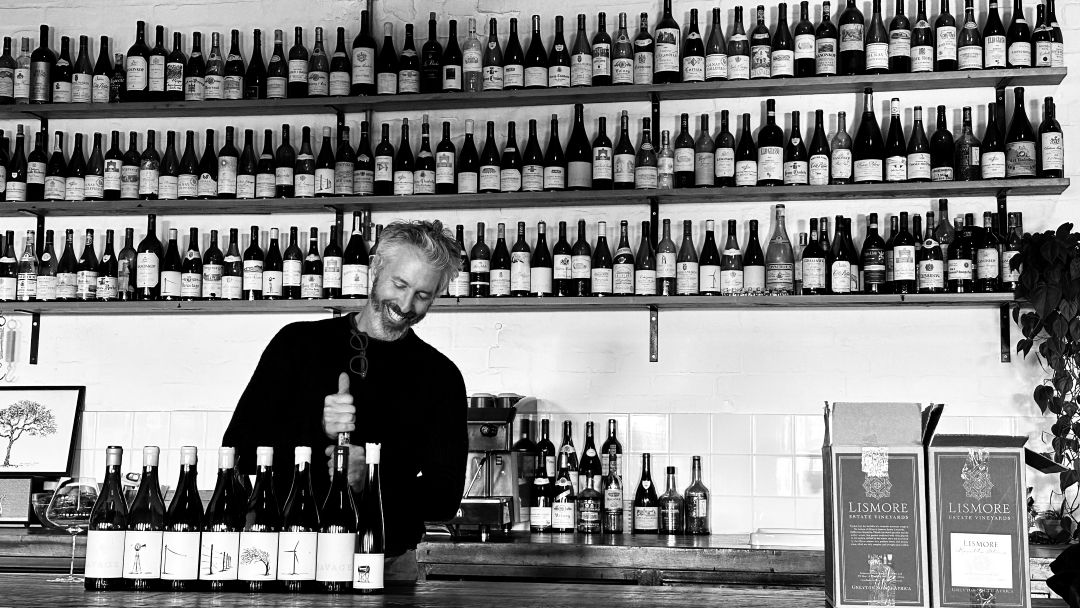

Duncan Savage, with the previous night’s libation on the shelves behind him.

Speaking of Savage, my final tasting is an enticing double act with Duncan Savage and Samantha O’Keefe, from Savage Wines and Lismore, respectively, together with Tembela Wines made by the former’s protégé, Banele Vakele. Both Savage and Lismore are paragons of contemporary winemaking whose wines habitually reach the apex of Cape wine. There comes a poignant moment. After tasting O’Keefe’s Viognier, Savage interrupts and pours an anonymous bottle, save for the same variety handwritten on a makeshift label. On December 17, 2019, a wildfire destroyed O’Keefe’s home, winery and around half of her vineyards with such ferocity that it almost took lives (see this video for her account of that day). She lost her entire 2019 harvest that was gestating in barrel…except for a tiny amount of Viognier that she had given to Savage for assessment. This bottle came from that batch. Memories of that fateful day must have flooded back as we tasted this “sole survivor.” Six years later, it is a testament to O’Keefe’s resolve and how winemakers rallied to her aid that Lismore has risen from the ashes—literally. Her latest releases are sublime, not least her exquisite contribution to the Cape Wine Auction.

The evening is spent at one of my favourite restaurants, Potluck Club. Apart from O’Keefe coming perilously close to destroying her taste buds with a chili off the Scoville scale (what is it with her and fire?), it is an enlightening and entertaining finale that finishes with a 1948 Port from Monis. South Africa has a tradition of making marvellous Ports that can age as well as those from Douro. Alas, since the halcyon days when it dominated consumption, the taste for fortifieds has dwindled to a niche category.

Day Twelve: Blaauwklippen, Home O’Clock

My final day begins with my second ParkRun, this time in Paarl along a river beneath the pearlescent mountain that inspired the region’s name. 28 minutes 29 seconds. Not bad. I loiter at the finish line to make sure Ronnie/Connie completes the course. Frankly, I could have fitted in another tasting by the time he crosses the line a few minutes behind a group of frail pensioners. Paarl has taken over from Stellenbosch as the region that has potential but is playing catch-up. Brookdale has shown what is possible, and a smattering of single cuvées from growers based in another region show well. In other words, Paarl needs more Brookdales.

Alex Starey gets dressed for my penultimate visit to Keermont.

My final day has just two appointments, Keermont and De Trafford in the Blaauwklippen Valley. This area has a slightly cooler micro-climate than the rest of Stellenbosch, with vines planted on its higher contours. My final visit is cancelled for an entirely understandable reason, so I am granted the first downtime since landing. I check out a local bistro with a tempting wine list, and the quality of Le Riche’s 2023 prompts me to dispatch a quick message to see if samples can be sent. You will find notes in this report.

But it is home o’clock.

Ronnie picks me up one last time. At the airport we bid farewell. I inform him that I expect to be beaten in next year’s ParkRun and wish him luck saving for a new car, one better equipped for rough terrain.

It has been another memorable trip. Hard work? Always. Fulfilling? Ditto. South Africa is never boring, never switches off, always on the go. Despite everything, it is the eternal optimist. Its wines dazzle with both quality and diversity, a polymath that is a dab hand at an array of styles catering to all tastes and to all budgets, a factor fatally forgotten by many wine regions. Headwinds are strong, more so than in other wine-producing countries, but then again, so are opportunities.

South African winemakers are just taking life day by day.

© 2025, Vinous. No portion of this article may be copied, shared or redistributed without prior consent from Vinous. Doing so is not only a violation of our copyright but also threatens the survival of independent wine criticism.

You Might Also Enjoy

Steenwold! South Africa: Ten Years On, Neal Martin, July 2025

South Africa: Where Are We Now?, Neal Martin, September 2024

White-on-White: Porseleinberg 2010-2020, Neal Martin, November 2023

The A to Z of South Africa, Neal Martin, November 2023

Growing Up ‘n Getting Wiser: South Africa in 2022, Neal Martin, September 2022

Back In Black: Kanonkop Black Label Pinotage 2006-2019, Neal Martin, August 2022

Show all the wines (sorted by score)

- Ahrens Family Wines

- Alheit Vineyards

- Alsina by Ntsiki Biyela

- Anthonij Rupert Wyne

- Anwilka

- Ashbourne

- Ataraxia

- Avondale Wine

- Avontuur

- Babylonstoren

- Backsberg Family Wines

- Badenhorst Family Wines

- Beaumont Family Wines

- Belle Rebelle Estate

- Bellingham Wines

- Benguela Cove Estate

- Bergsig Estate

- Black Elephant Vintners

- Boekenhoutskloof

- Boschendal Wines

- Boschkloof Wines

- Bosman Family Vineyards

- Brookdale

- Bruwer Vintners Vine Exploration

- Cape of Good Hope

- Cape Point Vineyards

- Cap Maritime

- Carinus Family Vineyards

- Cavalli Estate

- Colmant

- Constantia Glen

- Craven Wines

- Creation Wines

- Crystallum

- Curator

- Damascene

- Daschbosch

- David & Nadia

- Deep Rooted Wines

- De Grendel Wines

- Delaire Graff Estate

- DeMorgenzon

- De Trafford Wines

- De Wetshof Estate

- Diemersdal Wine Estate

- Durbanville Hills

- Du Toitskloof Wines

- Edgebaston Vineyard - David Finlayson Wines

- Eenzaamheid

- Eight Gates Wine

- Francis Wines

- Franschhoek Cellar

- Fryer's Cove

- Gabriëlskloof

- Glenelly Estate

- Graham Beck

- Great Heart

- Groot Phesantekraal

- Hamilton Russell Vineyards

- Hearth Wines

- Jayne's

- Jordan Wine Estate

- Journey's End Vineyards

- Kaapzicht

- Kanonkop Wine Estate

- Karabelo Masoleng

- Kara Tara

- Keermont Vineyards

- Kelvin Feku

- Ken Forrester Wines

- Klein Constantia Estate

- Kleine Zalze

- Kleinood Wines

- Kloovenberg

- Kumusha

- La Bri

- La Brune

- Lalela

- Lanzerac

- Leeu Passant

- Le Riche

- Lismore Estate Vineyards

- L'Ormarins

- Lourens Family Wines

- Luddite Wines

- Maanschijn

- Meerendal

- Meerlust Estate

- Merwida Wines

- Miles Mossop

- Minimalist Wines

- Momento

- Moya Meaker

- Mullineux

- Mvemve Raats

- Natasha Williams Signature Wines

- Natte Valleij

- Naudé Family Wine Company

- New Dawn

- Newton Johnson Family Vineyards

- Nitida Wine Cellars

- Off The Record Wines

- Old Road Wine Co.

- Olifantsberg

- Opstal Wines

- Paulus Wine Co.

- Pieter Ferreira

- Porseleinberg

- Quoin Roch Wines

- Quoin Rock Wines

- Raats Family Wines

- Rall Wines

- Restless River

- Reyneke Wines

- Richard Kershaw Wines

- Rock of Eye Wines

- Roundstone

- Rustenberg

- Saga Vineyards

- Sakkie Mouton Family Wines

- Saurwein Wines

- Savage Wines

- Schenkfontein

- Scions of Sinai

- Simonsig

- Southern Right

- Spier

- Springfield Estate

- Stark-Condé

- Storm

- Strydom Family Wines

- Swerwer

- Taaibosch

- Tembela Wines

- Terra Loci

- Tesselaarsdal Wines Pty

- Thamnus Wines

- The Foundry

- The Sadie Family Wines

- Thistle and Weed

- Thorne & Daughters

- Tokara

- Trade Wind Wines

- Van Loggerenberg Wines

- Van Niekerk Vintners

- Van Wyk Family Wines

- Vergelegen

- Vilafonté

- Villion Family Wines

- Visio Vintners

- Vulpes Wines

- Winshaw Vineyards

- Wolf & Woman Wines

- Yellowwood Winery