Browse using the new Vinous website now. Launch →

Printed by, and for the sole use of . All rights reserved © 2015 Vinous Media

In the Shadow of Mount Fuji

Most people know Sapporo, if at all, only as the site of the 1972 Winter Olympic Games. Aficionados of Japanese culture might have had the occasional beer of the same name. But wine? Surprisingly, almost 300 hectares on the large island of Hokkaido in the extreme north of the Land of the Rising Sun are planted with vitis vinifera. In terms of size, that is nothing, but its development has been a game-changer for domestic production.

Interestingly, it was Germans from Württemberg who first came here as flying makers, which is also why varieties such as Kerner, Zweigelt and Traminer are widely found on the island. Today, some such as the 2008 Lemberger Yoichi Fujimoto from Hokkaido Wine might even win a medal in Stuttgart.

From the new airport in Chitose, it takes almost two hours by car to reach the town of Otaru on the northwest coast, where the headquarters of the Hokkaido Wine Company is located. Although pioneering work had been done with hybrid grapes in the Tokachi subprefecture ten years before, in particular on a mutation of Seibel, 1974 is widely regarded as the birth year of viniculture on the island. Planting only began the following year, which is when Hokkaido Wine started its operations. Kimihiro Shimamura, whose father founded the company, studied enology in Weinsberg before returning home to produce his own wines. It was there where he met Gustav Grün, who is still an advisor to the company.

Nineteen seventy-nine was their first joint vintage, coinciding with the first Montana Sauvignon Blanc from Marlborough on New Zealand’s south island. Coincidence? At the time, only a few hundred cases were produced, both here and there. Today, Yuki Kasai, the outwardly shy yet self-confident cellarmaster, produces almost two million bottles a year. When I visited last summer, he proved the ageworthiness of his Pinot Blanc by pouring me a surprisingly young 2000 from magnum.

It is humorous that the name of the nearby town of Otaru also means “small wooden barrel” in Japanese, as most of the wines here see only stainless steel. As is so often the case in Japan, the view from the window of Hokkaido Wine’s laboratory is largely one of grain fields, goats, forests and the endless ocean. Other than the small garden across from the tasting room, with a few token vines, there is no vineyard in sight. Almost all the grapes are from Tsurunuma, two hours by car from Otaru, where Koji Saito, the winery’s spritely vineyard manager, has planted over a hundred hectares of vines.

There are over 25 different varieties here because nobody yet knows for sure which are best suited for the area. Among the ones that I liked the most was their spicy yet elegant 2008 Zweigelt. However, only 3,200 bottles are made each year. Retailing at 3,100 yen (approximately 26USD or 22.5EUR), it is not a cheap tipple, but then nothing in Japan was until the yen began to tumble last year. Nonetheless, that is a price that even most Austrian winemakers in Burgenland, the home or Zweigelt, only fetch in their dreams. The best wine of the afternoon was a juicy, off-dry Traminer made from 25-year-old vines, which by Japanese standards is already vieilles vignes.

For the most part, vitis vinifera can only be planted on the northwestern side of the island because of the snow cover found there in winter, often several meters deep, which protects the vines against severe frost. In the southwestern part of the island, winter temperatures seldom fall so low, leaving the entire region of Do Nan ripe for exploration. To the east, however, in the snow shadow of the mountains, there is virtually nothing other than hybrid grapes. Even if frowned upon by connoisseurs, the Yama Sauvignon grown there does show promise. The red grape is a new variety, a cross between the indigenous Yama Budou, or mountain grape, and Cabernet Sauvignon. Furano is the leading producer here. Surprisingly, winemaker Katsuyuki Takahashi’s smoky 1999 Zweigelt, with its flavor of cracked black pepper, proves that under the right conditions vitis vinifera can not only flourish here, but its wines can also age.

Suntory’s Tomi no Oka property with Mount Fuji in the background

The Dream of Pinot Noir

Although Silvaner, Kerner and Zweigelt are more widely found in Hokkaido, and can all make interesting wines, it is primarily Pinot Noir that is responsible for the gold rush on the island. Nobody embodies this new wave better than Takahiko Soga in Yoichi. The small valley of Yoichi Nobori that lies just west of Otaru is celebrated in Hokkaido as something of a grand cru. Having moved here only a few years ago, Soga has now planted some two and a half hectares of vineyards on the slope behind his little house—and only Pinot Noir. However, as Japanese law stipulates that a winery must produce a minimum of 6,000 liters a year to be granted an alcohol license, Soga currently uses purchased grapes to produce Müller-Thurgau, Kerner and a Passetoutgrain, a blend of Pinot Noir and Zweigelt. His aim, however, is to soon be bottling nothing but Pinot Noir from his own vineyards. The charm of the 2012 vintage aged in an old Francois Frères barrel, the first from his own grapes, reminded me of Volnay. On the label, he proudly writes Domaine Takahiko.

His energy has also infected younger vintners like Ryosuke Kondo from Kondo, who had already planted pinot noir before Takahiko Soga moved north, and Kadzuko Sasaki from Norakura. The latter studied winemaking in Dijon. In spite of Sasaki’s success with purchased grapes, she will only release her first estate-bottled chardonnay from her own vineyards in the southwestern corner of the island near Hakodate late next year.

Bruce Gutlove, who more than anyone else has profoundly influenced the development of the Japanese wine industry, also nourishes the dream of Pinot Noir. An American by birth, his love of wine led him to the University of California/Davis, where he received his winemaking degree in the early ’80s. After he had completed stints at Cakebread, Merryvale, Trefethen and Mondavi in the Napa Valley, Noboru Kawada of Coco Farms lured him to Japan in 1989. Coco Farms is based in Ashikaga, about an hour north of Tokyo by train. Actually, the estate is part of a school called Cocoromi Gakuen, which means something like “challenge”; it was founded for mentally disabled students in 1969. Kawada’s idea was and is that his students, who are considered second-class citizens in their own country, should be taught in the open air, so he started cultivating grapes in a nearby field. The conditions, though, were counterintuitive to fine wine production. With a meter of rain between blossom and harvest as well as insufficient diurnal temperature shifts, Cocoromi lived up to its name.

However, instead of taking the next flight home Gutlove stayed, and with better pruning, lower yields and later harvests managed to bottle acceptable wine in Ashikaga. It did not take him long, however, to realize that he would never be able to make a really fine wine here, so he began combing the grape-growing regions of Japan looking for better alternatives. Not having the money to cultivate 30 hectares himself, he decided to sign up young growers in the right locations and support them by buying their grapes. The company now produces around 180,000 bottles a year, their portfolio consisting of 17 different wines from numerous varieties and regions. Many are often the best of their kind in Japan, including the Yama no Chardonnay from Yamagata, that almost tastes like Carneros, the captivating Zweigelt Kaze no Rouge (Red Wind) and the white Kurisawa, an excellent blend from Hokkaido. The latter wine, though, is now partially custom-crushed in Bruce’s own winery and marketed by the vineyard owner under the Nakazawa Nouen (nouen means parcel of land) label. From Nakazawa’s oldest vines, Gutlove also makes a 100%-Traminer that sets new standards for this grape.

“Regardless of where I went and what I produced,” Gutlove told me with utter conviction, “the fruit that spoke to me with the most precision and clarity was almost always from Hokkaido.” And so, 20 years later, in order to fulfill his dream of “refreshing acidy and vibrant minerality in Riesling and Pinot Noir,” he decided to plant his own vineyards in Minami Sorachi. Although still a director of Coco Farms, his heart now lies in the far north, where he lives with his Japanese wife and their daughter. Although his own vines will only come into full production this year, his first wines from purchased grapes were from the 2012 vintage. Sold under the Kamihoro label, they include a Kerner from the Fujisawa Nouen in Yoichi that some have already called the best white wine that Japan has ever produced. Gutlove takes that all that praise with a grain of salt, though, knowing that the best is yet to come.

American winemaker Bruce Gutlove is one of Japan’s leading figures

In the Rain Shadow of Mount Fuji

In Japan itself, Coco Farms is known primarily for an off-dry sparkling wine named Novo that was originally made from the indigenous Koshu grape. The 1996, which by then was already being made from Riesling Lion, a cross between Koshu and Riesling, was the only Japanese wine selected by Shinya Tasaki, then the best sommelier in the world, for a state reception during the G8 summit meeting held in Okinawa in 2000, and it remains the company’s best-selling wine.

As with many of Japan’s most sought-after wines, the grapes for this sparkler come from Yamanashi, the birthplace of Japanese wine-growing in the rain shadow of Mount Fuji, about an hour’s drive southwest of Tokyo. Years ago, the Japanese emperor ordered his people to grow grapes there—and only there.

The vineyards in the region are planted primarily with Koshu, a variety often described as a variation of vitis vinifera, which Marco Polo is said to have brought with him from the Old World via the Silk Route over a thousand years ago. Genetic research, however, shows that Koshu is actually a cross between an old and still unknown variety, probably from the Caucasus, and a wild Japanese vine. There could thus be a grain of truth in the story. In any case, Koshu, which is over 90% vinifera, is considered the oldest variety to be taken seriously here and is also the signature grape that sets Japan apart from other countries—comparable to Pinotage in South Africa or Zinfandel in California. To top it off, Koshu matches perfectly with lighter Japanese cuisine.

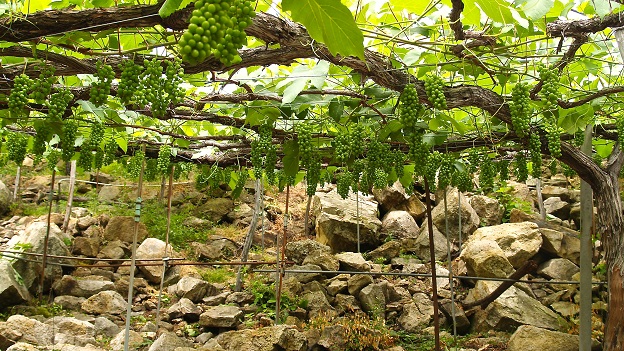

The first Japanese wine was produced in the Koufu basin in 1874. There, in the heart of the Yamanashi prefecture, is the only Japanese wine-growing area that a European would recognize as such. In all other areas, vineyards are only a small part of a patchwork of grain fields, fruit orchards, livestock and forest. Koufu alone boasts 500 hectares of vineyards, climbing gradually up a gentle slope, much like what one sees in Alto Adige. In virtually all the old vineyards, the grapes grow on pergola trellises. Unlike in Italy, though, the canopy of a single plant may cover an incredible 25 square meters and produce 500 to 700 bunches of grapes.

The majority of the crop in Yamanashi is sold as table grapes. As a leisure activity, many nature lovers come here from the capital over the long weekends to harvest fruit to take back to Tokyo to eat, paying up to 1,000 Yen (8.4USD, 7.3EUR) per kilogram for the right to cull them themselves. As wine growers can pay only 180 to 300 Yen (1.5-2.5USD, 1.3-2.2EUR) (and insist on lower yields, they rarely have the first shot at the finest grapes.

In addition, until 2008 there was a law that virtually prohibited wine producers from owning their own wine vineyards. Suntory was long the notable exception. This restriction has now been rescinded and some estates have planted their own vines, yet the change is, to date, only partially reflected in the taste of the wines. According to Naoki Watanabe, the universally acknowledged Suntory enologist: “With lower yields, we need to work on physiological ripeness to prevent the wines from tasting bitter and to ensure that they are more concentrated.” Interestingly, Suntory’s most famous wines from their Tomi no Oka vineyards in Yamanashi are not Koshu, although these have improved in quality, but from Chardonnay, Cabernet and Merlot.

The most well-known and consistently best producer of Koshu is Grace Vineyards. Its founder, Shigekazu Misawa, is the proud owner of 14 hectares of vineyards. He also buys grapes from an additional 15 hectares, from which his 33-year-old daughter Ayana produces 200,000 bottles a year, two-thirds of which are Koshu. Ayana learned her trade in France and Australia.

Their main winery, with its state-of-the-arts facility is in Katsunuma, but the new vineyards are primarily in Akeno, where the family until recently ran a restaurant called Aya. Sitting on the terrace in the spring, you could taste a selection of their wines while enjoying a beautiful view of the surrounding mountains. I still strongly recommend the 2013 Koshu Misawa Akeno Vineyard, without doubt one of the best wines in Japan, but you must now drink it elsewhere.

Interestingly, the old Japanese word for wine is 葡萄酒 (Budoshu), or grape alcohol. However, most Japanese today use the word ワイン、which is pronounced like wine, but written in Katakana, which is how they spell foreign words. The Japanese also have their own word for what today is often known as terroir: 風土 (fudo). It stands for a sense of culture, history, nature and climate. For Japanese connoisseurs like Miyuki Katori, who wrote the first true book on Japanese wine a few years ago, a good Japanese Koshu should have a subtle taste of fudo.

Katsunuma is the traditional heart of Yamanashi. Originally it was called Kai, but during the reign of the Shogun from Kamakura, the name Koushuu was introduced, which we write as Koshu when talking about its grape. One of the two largest producers here, even if small in comparison to wineries elsewhere, is Katsunuma Jyozo. In a good year they sell 180,000 bottles from their 30 hectares of vineyards. While the word Katsunuma refers to the place, Jyozo means “the production of alcohol,” be it beer, wine or sake. The 56-year-old estate manager, Yuki Hirayama, is always cheerful, energetic and enterprising. With 90,000 bottles, his Clareza is always one of the most reliable Koshus in the market: crisp, refreshing and extremely pleasant. He also produces a somewhat better Koshu called Todoroki, a subregion of Katsunuma, and a still more expensive one from the single vineyard of Isehara, which is regularly one of the best and most unique in any given vintage.

Their bottles also sport unusual packaging. As the name of one of the owners is Aruga, he had a colorful label designed, which says “Adega Aruga Branca.” Those not in the know might think this a Portuguese wine. Less well known is the Magrez Aruga Koshu, which Hirayama bottles for Bernard Magrez, the owner of Château Pape-Clement in Pessac-Léognan. Enologist Denis Dubourdieu also represents Bordeaux in Japan, advising Mercian on its Koshu from Kiiroka, definitely one of that large company’s showpieces.

Takahiko Soga makes Pinot Noir from his vineyards in Hokkaido

Hope in Export

Today there are more than 200 wine producers in Japan, of which more than 60 did not even exist 10 years ago. Ninety percent of them make less than 10,000 bottles a year. Not surprisingly, therefore, the three beer giants—Mercian, Suntory and Sapporo—lead the total market in wine production as well, at least in terms of volume. Of the three, Mercian has definitely invested the most in vineyards and cellars, but to date has never fully realized its full potential. Its rival Sapporo sells one and a half million cases of wine a year, but less than one percent of that is made from local grapes. For a long time, most “domestic” bottles were filled with imported bulk wine that was matured, bottled and sold under a brand name written in Japanese on labels that most of us would mistake for a true Japanese wine.

As the Statistics Bureau of Japan does not draw a clear distinction between table grapes and those intended for wine production, it is difficult to know exactly how many hectares of vineyards there are. Although the total area planted with vines covers about 17,400 hectares, at least 90% of that fruit is grown only for table grapes. Experts estimate the area dedicated to winemaking to be just over 2,000 hectares, of which more than a third is in Yamanashi.

At present, little Japanese wine, if any, is exported, and then almost exclusively to neighboring countries, where many Japanese work, or to the United States. The producers of Koshu of Japan (KOJ), a promotional organization, would like to bring about a change. However, Europe remains a closed market for most producers and the Japanese rules of production are sometimes so vague that the European Union (EU) does not allow their bottles to be imported as wine. For example, tartaric acid is added to most Koshu wines to give them more vibrancy. While this certainly does no harm—and is, after all, common practice in southern Europe--chaptalizing and acidifying a given wine at the same time is not currently prescribed by law, and the European interpretation is that what is not explicitly permitted is prohibited. However, another major hurdle has been recently overcome. Since August 2010, Koshu has been recognized as a grape variety by the Organisation International du Vin (OIV).

All of three centiliters is also proving to be a virtually insurmountable obstacle to the export of Japanese wine. The standard bottle in Japan contains 72 cl., but European authorities have decreed that wine can be sold only in 75 cl units. Bruce Gutlove, though, sees next to no potential for the export of Japanese wine anyway. He believes that the industry is too small, production costs too high, and demand—other than among the Japanese—prohibitively low: “We must instead bank on the pride of the locals.”

It is incredible that a country as regulated as Japan had absolutely no legislation until 1986 governing the sale of wine. The first true attempts came only later, but for years the laws remained so vague that little changed in the real world. It was not until 2005 that Japan finally introduced “guidelines” that are similar to those in Europe, but even these are still not legally binding. Since then, if the label reads “Wine of Japan,” the wine should be made exclusively from Japanese grapes. Further, if a vintage is mentioned on the label, then 75% of the must be from that year. The same applies for the grape variety, much as elsewhere in the world, at least for members of the Nihon Winery Kyoukai (Japanese Winery Association). However, participation is not obligatory; at present only about 25% of the domestic wineries belong and there are no legal repercussions for those who ignore the “guidelines.”

Moreover, individual winegrowing regions such as Yamanashi, Yamagata or Hokkaido are not legally demarcated other than as prefectures. And while thought is being given to introducing a system in Japan similar to those in Europe in order to protect those wine-growing regions, it will be a while before any of that is implemented.

Old vineyards in Yamagata

All Quiet on the Western Front

The other widely touted local Japanese variety is Muscat Bailey A, a cross of Muscat of Hamburg with Bailey, itself a mixture of American hybrids. Bred in 1920 by Kawakami Zenbei, one of the fathers of the Japanese wine industry, it blossoms late, can ripen reasonably early and, because of its thick skin, is resistant to most fungal diseases. It is fairly widely planted in Japan because it grows well in the country’s climatic extremes, but it seldom brings forth wines of much note unless it is cropped low, harvested fairly late and matured in wood.

Beyond Asahi Machi in Yamagata, Yashio Amemiya of Diamond Winery in Yamanashi is one of its leading proponents. With his long hair, beard and wire-rim glasses, he looks as if he has just stepped out of a film shot in the late ’60s on the corner of Haight and Ashbury, but his wines tell another story. With the experience he garnered while working with Patrick Bize in Savigny-lès-Beaune, he is one of the few producers who are able to coax elegance out of Muscat Bailly A, which is more often plump and at best ordinary. For years, his best wine was called Sai Sai, which has a positive meaning associated with color in Japanese, but in 2012 he released his first vintage of Vrille, which sets a new yardstick for the variety.

More Burgundian in character are the wines of Mie Ikeno, an editor who in her second career studied winemaking in Montpellier. When she returned home, she planted Chardonnay, Pinot Noir and Merlot at an altitude of 750 meters in the hills near Mount Fuji. With the first vintage from her own grapes in 2010, she caught the local wine world off guard. In particular, her Chardonnay was soon recognized as one of the best in the country. With a total production of only 5,000 bottles, though, she is not yet causing Suntory any sleepless nights.

Also in Yamanashi, but with a branch in Nagano on the west coast, is Manns. It is the brainchild of Dai Shimazaki, who studied winemaking in France in the late 1980s. Since then, he has taken this winery from strength to strength. The vineyards are manicured in picture-book style and the company has even developed a “raincut system” that sits over vines planted in the traditional European hedgerow style. Humorously, little umbrellas to protect each bunch of grapes against the rains that fall during the typhoon season in September at harvest have been around much longer, probably mimicking similar actions taken by apple growers.

Manns now produces about two million bottles a year, but the high-end Solaris label represents only a small fraction of that volume, the highlight of which is Magnificat, a blend of Cabernet and Merlot. Their mature 2006 was one of the finest red wines that I tasted on my first trip.

Like Sapporo in 1972, Nagano is associated with the 1998 Winter Olympics. Located on the western half of Honshu, Japan’s main island, some slopes are a little cooler and better sheltered from the storms arising over the Pacific Ocean. Chardonnay and Merlot more than Koshu are grown here. In addition to established wineries like Izutsu, founded in 1933, there are many newcomers such as Rue de Vin and Hasami, both of which were established only in 2009.

Here, in a garden that could be in Provence, lies the hermetic retreat of Toyoo Tamamura, an artist and poet well known in Japan who established Villa d’Est in 2003. Where mulberries once grew for the silk industry, the view is so impressive that Tamamura built a small restaurant below his house in 2004. “The customers enjoy sitting on the terrace,” he told me during our tasting. As the entire production totals only around 20,000 bottles a year, the wine is consumed almost exclusively at the winery itself or at selected restaurants in Tokyo. Cellarmaster Konishi Tohru recommends, above all, the 2013 Chardonnay Vigneron Reserve and the 2012 Merlot Tazawa Vineyard.

One of the most unusual vineyards in the region is that of Sogga in Obuse, run by Akihiko Sogga, the elder brother of Tahahiko Soga in Hokkaido. The difference in spelling between Soga and Sogga has to do only with the transcription of Japanese characters. Half crazy, half visionary, “being natural” is the leitmotif of Sogga’s wine production, despite all the problems that come with a humid climate. The grapes, certified organic, were long crushed with an old Knod basket press from Traben-Trarbach in Germany. The wines are neither acidified nor chaptalized and are often bottled with an alcohol content of less than 11.5%. What they lack in depth and body is compensated for by character. While 2009 was more conducive for Cabernet Sauvignon, in 2008 Merlot was better. Sogga’s aim is one day to produce only one premium red wine, Sogga Aka. Aka in Japanese means simply “red.”

Among the many new estates in Nagano, that of Akihito Kido deserves special mention. An old friend of Akihiko Soga, Kido established his own small property in 2004 after finishing his winemaking studies in Yamanashi and a stint at Hyasi Nouen in Shiojiri. When I visited, two of my favorite wines had just finished fermenting. Since then both the 2012 Pinot Gris Private Reserve and 2012 Cabernet Franc Private Reserve have been bottled and released. Both show what these varieties are capable of doing in Japan. With a total production of only 10,000 bottles a year, though, you are not likely to find either on your local supermarket shelf.

Sakai’s pergola-style trained vineyards

From North to South

While there are vineyards from Hokkaido in the north to Kagoshima in the south, most of the better-known wineries, if not in Yamanashi, Nagano and Hokkaido, are found in the prefectures of Yamagata, Akita or Iwate, halfway up north. Given the great distances, vintage quality can vary vastly from region to region. In general, however, 2009, 2006, 2004 and 2002 are considered to be the most successful years of the past decade. In contrast, 2010 was difficult overall. Because of climate change, the summers are now warmer and more humid, presenting vintners with fresh challenges. In fact, 2012 was one of the hottest vintages on record. That, coupled with high yields, made it difficult to make great wines. Two thousand thirteen, on the other hand, was marginally cooler. Given the moderate size of the crop, it is generally considered the best of the recent vintages.

In Yamagata, halfway between Nagano and Sapporo, the leading winery is no doubt that of Takeda. Founded in 1920, it is managed today by Noriko Kishidaira, one of the few women to hold a leading position in Japan’s wine industry. The old winery in Kaminoyama, which means high in the mountains, produces about 300,000 bottles a year. Kishidaira, who will soon turn 50, studied winemaking in Bordeaux and Burgundy. More than anything else, she brought back with her what she calls the “green doctrine” and rejects pesticides and chemical fertilizers. Besides the distinctive Château Takeda, a blend of Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Franc and Merlot in Bordeaux style, she also showed me a surprising Delaware, a white breed that has been grown in the United States since at least the 1850s.

In the prefecture of Nigata, the internationally acclaimed viticultural guru Richard Smart has been commissioned as a consultant and advises producers to plant lesser-known varieties like Petit Manseng or Tannat, which retain their acidity in warm weather and high humidity. It is therefore not unusual today to find more than a dozen different, new varieties in small vineyards. Sometimes these are crushed as field blends. In other cases, one of the varieties is bottled individually. In the case of Fermier, Takashi Honda, acting on one of Richard Smart’s recommendations, even planted Albariño. His first vintage was 2009—and it remains promising. Prior to this, the estate had made a name for itself with Cabernet Franc. Also impressive was a Petit Verdot from Marufuji under the Rubaiyat label, but only 150 bottles of this wine are produced each year.

Although this picture paints a fair portrait of the state of viniculture in Japan today, things are changing rapidly. Some of the finest wines are made today by estates that had not even bottled their first vintage when I began my research three years ago. Tremendous commitment but not large production runs, particularly of the premium wines, is the standard. It is high time, however, that instead of sake, beer and tea, we should be able to order a glass of Japanese wine to accompany a meal in the leading Japanese restaurants in Europe or North America. Koshu would be just the right start with sushi, sashimi or charcoal-grilled eel!

Takeda’s vineyards in winter

My Ten Favorite Whites

2013 Shion Koshu Madobe Dai Dai (88+?): Pale straw color. Very subdued aromas of apricot, lemon zest and clove oil. Light in body, and clean, delicate and fresh, offering a subtle peach flavor and textural softness. A slightly bitter herbal note, very typical for the Koshu from Yamanashi, cuts through on the finish.

2013 Katsunuma Jozo Arugabranca Koshu Isehar (89): Bright, pale yellow. The unusual aromas of gooseberry, dill and cassis are reminiscent of a Marlborough Sauvignon Blanc. Lean yet nicely balanced, with bracing acidity and a slightly herbal note, this Koshu from Yamanshi sets itself apart from the others through its purity, density and varietal intensity.

2013 Grace Koshu Misawa Akeno (89): Pale straw color. Fresh herbs, apple and lemon zest on the nose. Dense, ripe and concentrated, this Koshu from Yamanashi nonetheless remains bright, light-footed and elegant, with a distinct flavor of pear. Finishes crisp, dry and quite long.

2013 Gassan Koshu Soleil Sur Lie (88+?): Bright yellow. Lively aromas of grapefruit, lemon zest and white flowers. Densely packed and ripe on the palate, with intense citrus flavors supported by a strong acid structure. Brisk and firm on the finish, this Koshu is from the more northerly climate of Yamagata.

2013 Suntory Koshu Tomi no Oka (88): The 2013 from Suntory’s Tomi no Oka property is a bright but subtle interpretation of Koshu. Perfumed aromatics lead to a delicate expression of apricot and peach as this inviting white wine opens in the glass. Not quite as varietally complex as the other four Koshus highlighted here, but fun to drink.

2013 Nakazawa Vineyard Traminer (89): Greenish yellow. Expansive nose exudes chamomile, rosewood and white pepper scents. Rich, unctuous and quite dry, this Traminer from Hokkaido is nonetheless balanced by refreshing acidity, providing the wine with an agile finish.

2012 Kamihoro Kerner Fujisawa Nouen Yoichi (90): Greenish yellow. Alive in the glass, showing subtle apple, green pear and floral notes. This rich yet delicate Kerner from Hokkaido is almost Alsatian in style. Intensely perfumed, energetic and nonetheless restrained, with slightly angular contours and a distinct varietal personality, this is certainly one of the best white wines that I have ever tasted from Japan.

2012 Kido Pinot Gris Private Reserve (89): Pale, bright yellow. Intense aromas of lemon blossom, nut oil and spices, complicated by a leesy nuance. Dense and supple on the palate, with a slight warmth leavened by a refreshing citrus bounce and a touch of minerality. Finishing quite dry and persistent, this reserve bottling from Nagano is in the style of an Alsatian Pinot Gris.

2012 Mie Ikeno Chardonnay (89+?): Light yellow. Fresh pear and quince aromas are complemented by white flowers and lemon zest. Delicate and lively on the nicely balanced palate, this Chardonnay from Yamanashi offers fresh citrus and orchard fruit flavors along with a hint of candied ginger. Finishes very naturally, with a touch of chalkiness and very good spicy persistence.

2012 Villa d’Est Chardonnay Vigneron Reserve (89): Bright yellow. Delicate aromas of ripe pear and melon, with a hint of lemon pith. Light and subtle in texture, this Chardonnay from Nagano offers both orchard and citrus fruit flavors, with hints of lees and buttered toast and a touch of honey. Finishes with slightly smoky persistence.

My Ten Favorite Reds

2012 Diamond Winery Muscat Bailey A Chante Vrille (88+?): Inky ruby. Minty redcurrant, tobacco, graphite and fresh flowers on the nose. Lush, dense and fine-grained, with a slightly floral lift to the warm dark berry flavors. Both suave and solidly built, this unusual wine from Yamanashi finishes with surprising fleshiness, sweet tannins and good length.

2011 Villa d’Est Merlot Tazawa Nouen (89): Vivid ruby. Blackberry, cassis and mint aromas are complicated by a hint of vanillin oak. A firm cherry flavor is subtly accented by floral pastille and cracked pepper nuances that that bring both balance and focus. Closes on a sweet note, with a spicy edge, gentle tannins and a touch of licorice. This Merlot from Nagano is vaguely reminiscent of Pomerol and should age well.

2012 Mie Ikeno Merlot (88): Bright ruby-red. Blackberry, Bing cherry and licorice aromas are lifted by notes of rosemary and thyme. Although very approachable, the black fruit flavors also offer surprising depth. The tannins are suave yet quite firm for a Merlot from Yamanashi, with the finish boasting good length. I might mistake this for a Montagne Saint-Emilion in a blind tasting.

2012 Norakura Nora Rouge (88): Deep ruby. Subtle aromas of cherry and mint, plus a hint of chocolate. Supple, spicy and lively, with fresh cherry flavors that become sweeter on the back of the palate. Finishing with soft tannins and refreshing spiciness, this elegant merlot from Hokkaido was one of the pleasant surprises in our final tasting.

2012 Domaine Takahiko Pinot Noir Nanatsu Mori (89): Vivid ruby. Herbal aromas of red berries, anise and rose, with a gentle smoky overtone. Supple and already quite open, this Pinot Noir from Hokkaido offers flavors of raspberry, boysenberry and candied licorice. Gently bitter tannins give shape to the almost Burgundian finish, with a white pepper note lingering on the back of the palate.

2012 Kondo Pinot Noir (89): Bright ruby. A vibrant redcurrant aroma shows good clarity, picking up both smoky and floral nuances with aeration. Tangy and focused on the palate, this Pinot Noir from Hokkaido offers flavors of strawberry, bitter cherry and cracked pepper. Finishes clean and nervy, framed by slightly dusty tannins.

2012 Kido Cabernet Franc Private Reserve (91): Bright ruby. An inviting floral quality complicates wild strawberry, tobacco and licorice on the nose. Fresh, rich, juicy and intense, with a cassis flavor lifted by a note of eucalyptus. With its lively but tame tannins accentuating the palate, this pure, concentrated Cabernet Franc from Nagano is certainly one of the finest red wines that I have ever tasted from Japan.

2012 Sakai Toriagesawa Kanezawa (90): Inky ruby. Bright aromas of cherry, plum, spices and menthol are nicely interlaced. Nervous and layered on the palate, the 2012 Cabernet Sauvignon from Yamagata possesses a lovely radiance and cool-climate texture. Sweet floral depth and spice notes add lift to the finish. The last three vintages from this estate have all been very successful.

2009 Suntory Tomi (88): Deep ruby. Cassis, licorice and mint on the nose, along with a hint of graphite. Sweet, dense and almost overblown, this Bordeaux blend from Yamanashi is Suntory’s flagship wine. The palate-saturating tannins are soft and savory but slightly herbal, probably from the high percentage of Petit Verdot in the blend. Finishes with a floral element.

2008 Château Takeda (90): Deep, bright ruby. Blueberry, licorice and mint on the alluring nose. Pure, concentrated and delicate but still a bit medicinal, with blackberry and spice flavors rising on the palate. This is a distinctly cool-climate Cabernet Sauvignon/Merlot blend from Yamagata, with slightly dusty tannins promising a better future after another few years of bottle aging.--Joel B. Payne