Browse using the new Vinous website now. Launch →

Printed by, and for the sole use of . All rights reserved © 2015 Vinous Media

Jura: What About The Future?

“Chardonnay was in the Jura before Savagnin,” claims Stéphane Tissot, “and it reflects the differences in our soils with more nuance than Savagnin.” For consumers who associate this French region on the northwestern foothills of the Alps principally with Vin Jaune, his statement may come as a surprise. The local authorities, though, agree completely. They see Chardonnay as the future of the appellation and are paying producers to rip out old vineyards planted with Poulsard and Trousseau and replace them with Burgundian clones. “This is ridiculous,” believes Jean-François Ganevat, who loves those two indigenous red varieties, “not only because we are losing part of our heritage, but because the government will only pay for clones, not massale selections, which are much better.”

Domaine Tissot's La Tour du Curon Vineyard

A Little Historical Perspective

Sadly, the Jura has already lost a large part of its vinous history. Before Phylloxera struck in the late 19th century some 20,000 hectares of vineyards covered the southern slopes of these gentle hillsides. Today, only 1,600 remain—and were it not for Henri Maire, who with money from the Marshall Plan almost singlehandedly saved the region from extinction, there would probably be considerably less. While collectors turn up their noses when they hear mention of his Vin Fou, the sparkling wine with which he paid the bills, all of the local growers I have met remain grateful for what he did. “For years, he bought all of our grapes,” explained Raphaël Fumey. “Were it not for him, most of us would have gone out of business.”

Jean-Francois Ganevat in his cellar

Today, the Henri Maire estate makes wines only from their own 250 hectares of vineyards. The brand, however, has fallen on hard times since Henri Maire himself passed away. Earlier this year, it was purchased by Jean-Claude Boisset, a négociant based in Nuits-Saint-Georges. The role of the region’s largest buyer of grapes is now played by La Compagnie des Grands Vins, better known to most in the wine trade as Les Grands Chais du France. The other major player is Fruitière Viticole, the largest co-operative in this otherwise small region. For the moment, though, the headlines are made by smaller growers like Stéphane Tissot, Jean-François Ganevat and Laurent Macle, whose wines embody the potential of the region.

Varietals, Terroirs and Microclimates

Those who see Chardonnay as the region’s future often point to the similarities between the Jura and the Côte d’Or. In both appellations, the vineyards run from northeast to southwest above the Saône River. The vineyards in Burgundy largely face south and east, while those in the Jura face south and west. Yes, the best Chardonnay produced here can compete with the finest from Chablis or Meursault, but there are major differences. Most of the heart of Burgundy is on vertical fault blocks that feature exposed, very chalky soils from the Jurassic period. The vineyards in the Jura, on the other hand, are largely on rolling hills that slipped down the Alps towards the plains of the Bresse, bringing large amounts of marl from the Triassic era to surface. As the vineyards in both regions are planted on a mixture of these two types of soil, what does that mean? Burgundy is predominantly limestone, the Jura mostly chalky clay.

Vineyards in Pupillin. Snow is manageable in the winter, but rain in other parts of the year can be problematic

Further, on average the Jura receives almost 50% more rain than Burgundy. As most of the showers arrive from the west, this should come as no surprise. The clouds blow over Beaune and, blocked by the Alps, drop their water in Arbois. A drier region like Alsace would welcome more precipitation, but the Jura sees a meter of rain each year, which can wreak havoc during flowering, engender disease in the summer, and dilute the grapes at harvest.

Given these weather conditions, it is not surprising that Savagnin accounts for a full quarter of total plantings. Although it ripens late, its thick skin, high natural acidity and unique flavors have long made it the Jura’s unique sales proposition. Not only does Savagnin seldom suffer from mildew or grey rot, it thrives on the marl soils that are so common here. Given its proclivity to develop flor, a film of yeast on the surface of a young wine in cask, Savagnin was once thought to have come from Jerez in Spain, but genetic studies have now proven that it is identical to Traminer. Not only that, the variety originated here and not, as was long thought, in the southern Tyrol region of what is now northern Italy. Further, Dr. José Vouillamoz, the renowned father of modern genetic tracking, considers Savagnin to be one of the founder varieties and thus the ancestor of a host of other grapes, including the local red Trousseau.

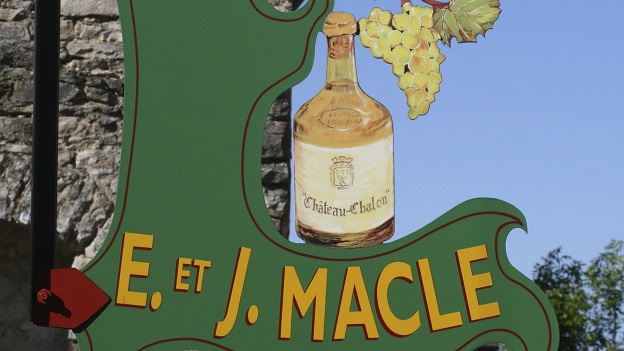

62 cl Clavelin bottles are used in Château-Chalon for the white wine made with Savagnin in the Vin Jaune style

Known in Spain and Portugal as Bastardo, and widely planted in the Dão, Trousseau is, like its brother Poulsard, no longer in fashion. “It needs gravelly soils,” explained Jacques Puffeney. “Otherwise it tends to rot.” What sells today is not only Crémant du Jura, but also Macvin. The latter is a beverage much like Ratafia in Cognac, but it must be made with the marc of the same wine and is only allowed to be sold by smaller estates. “It pays for the children’s schooling,” said Raphaël Fumey as he proposed a last glass after we had finished our tasting.

While many of his colleagues are scaling back their production of Macvin, almost all see a future in Crémant. Not only is it a competitively priced alternative to Champagne but the base wines can be cropped at levels that are profitable, harvested early before the rains, and turned into bubbles by a third party that controls the process. The finest examples, though, like the BBF from Stéphane Tissot, are made in the style of growers Champagnes.

The Risky Road to Vin Jaune

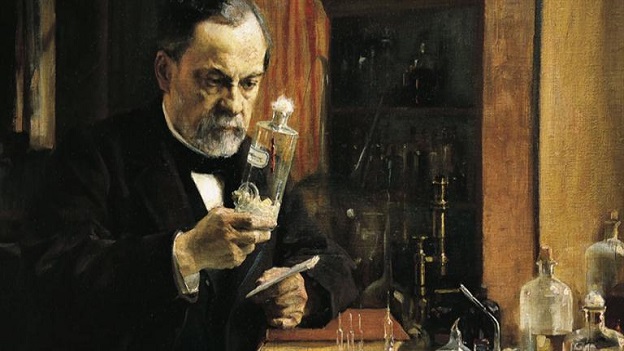

Everywhere you turn in the Jura, there is mention of Louis Pasteur, the region’s favorite son. Not only did he famously say that wine is the healthiest and most hygienic of beverages, his work on micro-organisms greatly facilitated the average vintner’s life. It is often forgotten that his recommendation of what we today called the pasteurization of musts to prevent bacterial spoilage was once a common practice and even became extremely popular in the late 19th century in California, where the nascent industry held him in reverence.

Renowned French chemist Louis Pasteur, painted by Albert Edelfelt in 1885, advanced a number of key scientific theories

It was Pasteur's work on Vin Jaune, however, that truly advanced this region’s fame. Understanding how the voile, the French term for flor, developed enabled local producers to make more Vin Jaune and less vinegar, both of which are induced by layers of yeast that settle on the surface of a wine in cask. Mycroderma vini is a savior, Mycroderma aceti a pest.

While scientists today know more about the nature of these two yeasts, they still have not found any efficient or effective way to control them. For that reason, every barrel of wine starting down the long road to becoming Vin Jaune is tested twice a year to monitor its development. Any barrels that are not maturing properly are quickly pulled from the program and put to other use. For smaller growers, this may mean the difference between, after the required six years of cask aging, producing three or only one barrel of Vin Jaune in any given vintage. Sometimes it is even none.

Cathusian cellars at Domaine Pignier in Montaigu

Whether they are in Arbois, Château Chalon or L’Étoile, the three sub-appellations of the Côtes du Jura, each estate has its own ideas on the desired temperature and humidity fluctuations necessary in the cellar to achieve the best results for Vin Jaune. All, though, bottle it in the 62-centiliter Clavelin, which is more or less what is left from one liter of Savagnin after six years of maturation. As this bottle size is not allowed to be sold in the United States, American consumers must sneak their favorite wines home in their own luggage if they want to taste these expressions of the Jura.

Overview of Recent Vintages for Vin Jaune

According to Stéphane Tissot, “both 2009 and 2005 worked well for Vin Jaune.” He then added that “sometimes the little vintages can be excellent. Ironically, those that are great for Chardonnay might not work at all.”

Whether 2014 will be one of those remains to be seen, but it was a difficult vintage. As Jean-François Ganevat observed, “there was too little sun in the summer and too much rain in the winter.” Francois Duvivier from Domaine du Pélican, on the other hand, was happy with both the quantity and the quality, showing how disparate the results can be between the northern and southern parts of this small region.

Two thousand thirteen was equally chaotic. Everything ended better than expected, “but it was certainly a better vintage for the reds than the whites,” observed Stéphane Tissot. “But it will not be a vintage to lay down,” added Jacques Puffeney. The last of that ilk was 2011, which was good for both colors.

Emmanuel Houillon and Pierre Overnoy in their vineyards

A Slow Changing of the Guard

Along with Pierre Overnoy and Jean Macle, Jacques Puffeney was one of the diehards of the past generation. They were, if you will, the three musketeers of their generation, fighting for quality in an era in which price and volume ruled. Not only were they at the forefront of more organic ways of farming, they also introduced low- and no-sulfur regimes that not only inspired the current generation of winemakers but have also become almost the norm in the Jura today. Indeed, there are few regions in France—or for that matter in the world—where so many estates are biodynamic and so many wines are bottled with no added sulfur. While I admire the former practice, I have often had problems with the latter, especially if the wines are not stable. Uncontrolled oxidation is not my thing. Perhaps, though, this region’s long experience with the oxidative production methods of Vin Jaune has taught them a lesson that others might want to learn if they toe to that orange line. In any case, I have seldom tasted as many good examples of wines bottled with no sulfur anywhere else. However, how stable they will be after transport and storage in a third party’s cellar I do not know.

Sadly, 2014 will be Jacques Puffeney’s last vintage. He is retiring this year, but none of his children were interested in assuming the responsibilities of the estate. He thus sold most of his vineyards to the neighboring Domaine du Pélican. Owned by Guillaume Marquis d’Angerville and Francois Duvivier, it is the first time that a renowned estate from Burgundy has set up shop here and certainly bodes well for the future. Puffeney must secretly hope that a phoenix will rise from his ashes.

--Joel B. Payne

Show all the wines (sorted by score)

- Champ Divin

- Domaine André et Mireille Tissot

- Domaine Berthet-Bondet

- Domaine Daniel Dugois

- Domaine de la Borde

- Domaine de la Pinte

- Domaine de la Tournelle

- Domaine du Pélican

- Domaine Frédéric Lornet

- Domaine Ganevat

- Domaine Jacques Puffeney

- Domaine Labet

- Domaine Macle

- Domaine Peggy et Jean-Pascal Buronfosse

- Domaine Pierre Overnoy

- Domaine Pierre Richard

- Domaine Pignier

- Domaines Henri Maire

- Fumey & Chatelain

- Les Chais du Vieux Bourg

- Rijckaert