Browse using the new Vinous website now. Launch →

Printed by, and for the sole use of . All rights reserved © 2015 Vinous Media

Memorable Moments from a Turbulent 2018

BY DAVID SCHILDKNECHT | JANUARY 2, 2019

While I lack Neal’s talent or experience in this genre, I was invited to address one or more personal highlights of my year. If you and I are lucky, the recitation might pleasantly distract us from the symptoms of social and governmental dysfunction that have been so conspicuously in evidence. There was one vinous event in which I participated that could conceivably be set alongside the year’s many cultural calamities as “historic.”

Comet Wine

My Vinous colleagues enjoy far more regular exposure to venerable and legendary fermented beverages than I do. But thanks to a tasting organized to commemorate the 300th anniversary of Weingut Geheimer Rat Dr. von Bassermann-Jordan (“Bassermann-Jordan” for short), I suspect I may now have one up on them when it comes to wines of the Napoleonic era – or at least, of ones that can be not only contemplated in awe, but still enjoyed as wine. Granted, I have only tasted one beverage meeting those criteria, but doing so was indubitably a high point of my year.

The “comet wines” of 1811 became legendary not just because the growing season coincided with a then-unprecedented nine months during which a comet – Comet Flaugergues, or the Great Comet of 1811 – was brilliantly visible to the naked eye (a record shattered in 1997 by Comet Hale–Bopp) but because it set viticultural records that, by remarkable coincidence, were only approached again this very year. Andreas Jordan – who took the reins of his family’s estate in 1783 and introduced the Pfalz’s first all-Riesling vineyards as well as its first vineyard-designated bottlings – chronicled with mounting disbelief the earliest flowering ever recorded, followed by a perpetually balmy summer, culminating in a September 8th entry: “grapes already completely ripe.” That freakishly precocious ripening season of 1811 – like certain momentous events (notably of 1812) – was widely attributed to the comet. Would that those of us gathered at the end of August for this commemorative occasion and almost incredulously sharing anecdotes of Riesling already on the cusp of ripeness could pretend that vintage 2018 had any similarly singular, supernatural explanation. (I promised to try to distract us from social and political calamities, but climatic calamity is already baked into contemporary discussions of wine.)

Bassermann-Jordan’s 1811 Forster Ungeheuer isn’t just one among many legendary “comet wines.” It is preeminent among those from the German-speaking world, its rapturous reception by Goethe having been commemorated in the great man’s West–östlicher Divan and by Bismarck in the pronouncement, “This Ungeheuer is ungeheuer” (meaning uncanny, prodigious), a meme avant l'Internet that guaranteed this wine and Weingut Bassermann-Jordan a second century of fame. The estate’s commercial director Gunther Hauck and cellarmaster–vineyard manager Ulrich “Uli” Mell presided over the opening of a bottle among friends and winemaking colleagues earlier in the summer, then over that of two bottles among wine critics and other professionals at the tercentennial festivities. Reportedly, six bottles now remain, part of a vast collection, alone among many that famously once resided in Mittelhaardt cellars to have survived the post-World War II occupation by thirsty French troops. Because even as Hitler celebrated military victories and delusions abounded of a “thousand-year Reich,” Friedrich von Bassermann-Jordan was, with remarkable prescience, so thoroughly walling in his Schatzkammer that none but the initiated suspected its underground presence.

In the course of a major 2006 cellar renovation, Achim Niederberger – whose widow Jana now presides over the three estates that he reunited under common ownership after a century and a half: Bassermann-Jordan, von Buhl and Deinhard-Von Winning – moved the entire rarities collection into the huge, deep garage under his villa in Neustadt, where renowned cellarmaster Hans-Günter Schwarz, formerly of Weingut Müller-Catoir, was then vinifying the small crop from Villa Niederberger’s immaculately tended vines. Simultaneously, Schwarz presided over systematic re-corking of Bassermann-Jordan’s treasures.

Here I am in 2006 admiring a bottle of the 1893 Forster Ungeheuer that Schwarz and Niederberger allowed me to take outside long enough for my friend and wine photographer Armin Faber to snap some shots.

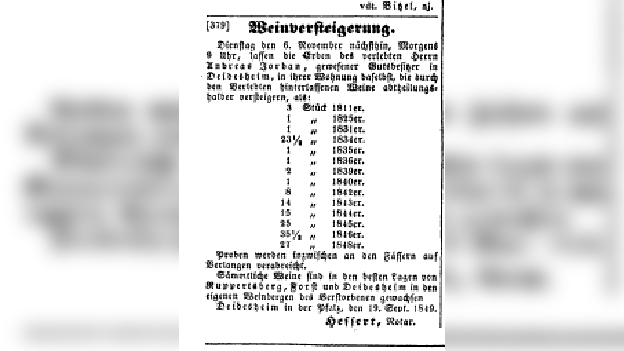

The precious 1811s were among those wines re-corked in 2006, with one bottle reportedly sacrificed to top off the others. How often and at what intervals these bottles were previously re-corked, nobody could say, though Uli Mell advised me that “you’d be surprised how many bottles 50 or more years old and known never to have been re-corked got passed over again in 2006 because their fills were still more than adequate.” Their corking and topping-off history is just one of the mysteries surrounding Bassermann-Jordan’s 1811s. There’s an 1849 announcement for the auction of wines from recently deceased Andreas Jordan’s estate that lists as its premier and by far oldest offering "3 Stück [1,200-liter Stückfässer]” of still-unbottled “1811er Forster.” That may be the source of the wine that Bismarck tasted, but there is good reason to suspect that the remaining bottles of 1811 Ungeheuer represent part of the same lot – or were bottled around the same time – as those whose praises Goethe sang in 1819 after having had them delivered to a spa where he was “taking the cure.” So the wine we drank was probably bottled 3-6 years after harvest, which was typical for the time.

Versteigerung 1811er

Is it really Riesling? Andreas was so ardent in his endorsement of this grape and of reiner Satz (mono-cépage) planting, then rare if not unprecedented in the Pfalz, that it seems likely the best portions of Ungeheuer – and the bottles Jordan retained for his own cellar – would by then have been dominantly Riesling, which also renders unlikely that the 1811 Ungeheuer issued from old vines. If other grapes are implicated, the most plausible candidate is some variant of Traminer, a grape associated with the Pfalz both before and after, and in fact known to have persisted in Riesling-dominated Mittelhaardt vineyards well into the 20th century. (Goethe & Goethe’s classic 1876 Atlas der wertvollsten Traubensorte, in which Roter Traminer is one of the 27 “most valuable” grape varieties promised in its title and profiled in detail, Mittelhaardt villages represent the sole habitat mentioned – not Alsace, not Alto Adige – with the added remark: “In other wine lands it is found only to a lesser extent, often only sporadically.”)

This being German Riesling, one is bound to wonder whether the wine finished fermenting with any significant residual sugar. Apparently, that hasn’t been tested for. Intriguingly, I happened upon a 1917 tasting note – from an event, incidentally, at which this was among the more youthful wines – describing it as “still harboring a hint of sweetness [einen Hauch von Süsse].” But there is considerable reason to doubt that the descriptor “süss” in 19th- or early-20th-century German wine literature should be interpreted literally or analytically. Certainly a century later I did not discern sweetness.

As you can see the wine wasn’t nearly as dark in color as one would have anticipated after so many years.

So how did it taste? Well, the first and most amazing thing to emphasize is that it was both enjoyable as wine and recognizable as a Forster. I once cited a 108-year-old Bassermann-Jordan Ruppertsberger to illustrate how such drinkability and typicity can accrue not just to a very old Riesling, but to one from a good rather than great site in a good but by no means great vintage. Their 1811 Forster Ungeheuer, though, reflected a signature site in a (shooting) star vintage. The aromas were high-toned but not attenuated. The flavors were still animating and juicy, and not at all dried out; the zesty and smoky black-tea-like bitter elements were a source of pleasing stimulation rather than blockage. Cooling hints of fennel and mint alternated with piquant citrus rind, while sappy, saline, site-typical savor set the salivary glands into motion. If that strikes you as “just another typical Schildknecht tasting note,” in a way it should, because this wine’s age was a cause for wonder in large part precisely because it did not taste at all old. And although you probably already guessed this was coming, it really did finish with a veritable comet’s tail.