Browse using the new Vinous website now. Launch →

Printed by, and for the sole use of . All rights reserved © 2015 Vinous Media

German Riesling 2017: No Pfalz Sense of Security

BY DAVID SCHILDKNECHT | MARCH 20, 2019

What comes of a growing season in which Nature keeps her foot firmly on the accelerator and doesn’t hit the brakes until the last second? One answer can be found in the reactions of German vines and vintners to record-setting conditions in the course of 2017, and in the often distinctively delicious but highly diverse Rieslings that resulted.

Welcome to the New Abnormal

“I’m starting to believe that there are no longer any normal years,” declared veteran Von Buhl vineyard manager Werner Sebastian – a sentiment with which most German Riesling growers would probably agree. Meteorological extremes are putting a strain on the vines as well as their growers, and it’s a fair guess that only those who take pains to adapt to the new climatic realities will be capable of rendering outstanding wines. Even in a growing season that their predecessors would have deemed traumhaft – a dream come true – striking the right balances in yield and canopy management, strategizing harvest, and otherwise intuiting the consequences of unprecedented meteorological conditions are all bound to keep quality-conscious Riesling growers up at night.

The 2017 season in Riesling Germany entered on the tail of a frigid January, something it is less and less possible to take for granted, and the significance of which should never be underestimated. Very low temperatures insure that vines enter a proper dormancy, and kill off spores and larvae that might later put fungal and pest pressure on growing vines and ripening fruit. But an astonishingly warm February and March of 2017 set the temperature template for what followed, including record early bud-break, flowering, veraison and harvest. Fortunately, late winter and spring were not only abnormally warm, but on the whole well-watered. The exception was a virtually rain-free April, which, as I suggested in previewing the 2017 vintage in Riesling Germany and Austria, might help explain an anomaly in the eventual wines: high levels of acidity from a year of warmth and precocious ripeness. The most plausible theory (to put it in teleological-anthropomorphic terms) is that vines deprived of water during the spring adjust in anticipation of a dry season and thereby conserve and direct their energies in ways that will help them through subsequent summer water deprivation without suffering metabolic imbalances (including acid depletion). By this theory, what explains the extremely low acid levels of 2003, for instance, is not merely the infamous heat and drought of that summer, but the fact that it came on the heels of a rainy spring that led vines to adjust their inner workings in anticipation of water without end. And it may well be that April is the critical month for determining the vines’ future comportment.

Again in 2017, veteran Hansjörg Rebholz’s rendered superb Rieslings and Pinot Blancs from the Southern Pfalz vineyards around Birkweiler and Siebeldingen. But recent achievements by Volker Gies at nearby Weingut Gies-Düppel, while little-noticed internationally, are also becoming exciting.

Rudely Interrupted – But Not for Long

Beyond the realm of theory is the cold, hard fact that April 19–24, 2017 delivered deep frost to vines that had budded out unprecedentedly early. Temperatures in many regions dipped so low at vine height (–3 to –6˚C/21–26˚F) that sprinklers, burning straw or hovering helicopters could not save the young shoots. Moreover, this frost inflicted damage on many steep and high-elevation slopes that are usually spared. In some instances, secondary growth emerged and eventually caught up. But many growers lost a significant share of their potential crop, and in certain localities that loss approached devastation. At this juncture, Nature indeed momentarily stepped hard on the brakes, because vines can never immediately resume their previous growth pattern once traumatized by deep frost. And yet May and June were so unremittingly warm (and, in the case of June, dry as well) that flowering, like bud-break, set records for precocity, and the development of clusters was turbo-driven, especially where the frost had reduced their numbers.

Depending on the sector in question, July and early August brought rainfall that was either entirely welcome or a bit too much at once for the vines to properly utilize. But above-normal temperatures continued. Most of August featured stifling heat, punctuated in some places by fast-moving, savage storm fronts that visited hugely destructive hail on parts of the Mosel, Rheingau and Rheinhessen. By the beginning of September, harvest of non-Riesling grapes was in full swing throughout almost all German growing regions, and at most addresses the commencement of Riesling harvest broke records that had been set in 2015 or 2003. As usual, the Pfalz went first. And soon after, a welcome autumn chill arrived too. Rain fell throughout Riesling Germany in mid-September, and in many sectors, botrytis emerged. But continued cool temperatures helped hold it at bay, and clear skies subsequently dominated. Predictably, the Mosel and Saar were the last to finish picking. But most estates, regardless of region or precise harvest window, recorded a record early start and a record-setting pace. Even at large establishments, a harvest that might typically take six to eight weeks was crammed into a three- to four-week period, and some small domains harvested the majority of their Rieslings within a mere 7–10 days. (Spoiler alert: 2018 set new records for earliest-ever starting dates, but also for lengthiest-ever picking windows.)

Given the prevailing warmth and precocity of vintage 2017, it is superficially tempting to imagine fruit that was deprived of long hang time, or of what many growers and other observers believe is a critically important period of chilly weather for building complex and attractive Riesling aromatics. But in fact, flowering in most sectors was nearly as precocious as harvest, and fruit enjoyed at least the proverbial hundred days’ hang time. Moreover, cool temperatures set in soon enough in September that even growers in the Pfalz benefited. Those cool temperatures also largely staved off any explosion of grape sugars, let alone an intrusion of overripe flavors, and insured acid retention that, as just mentioned (and as discussed in my preview), was still well above average at summer’s end. The Rieslings of 2017 also share levels of sugar-free dry extract that are extremely high – almost freakishly so. Nor can this be explained by low yields, though that is the explanation most growers in badly frost-afflicted sectors understandably offer.

Buckle Your Seatbelt Before Tasting

The overall upshot of 2017 for German Riesling is wines possessing palpable density, insistently efficacious acidity, and an edgy sense of energy that occasionally translates into mouth-shaking eruptions. At times and from certain places, there is a rustic or gruff side to the wines’ grip and phenolic intensity, something accentuated in those sectors where botrytis turned into a significant factor. Yet many of the dry wines evince a welcome impression of subtle oiliness – schmaltz, if you will – that helps assuage any tendency toward angularity. And apropos of botrytis, even though the share of vines and clusters visited by noble rot this vintage was small, when taken on top of the extremely low yields in hail-affected sectors – especially in the Mosel and in the Rheinhessen Wonnegau – the result was a significant number, albeit in tiny volumes, of stratospherically high-must-weight elixirs, quite a few of which were still fermenting when I completed my on-site tastings in mid-November.

If ever a vintage were going to test whether dry extract is something one can organoleptically detect, or whether (in addition to manifestly – and, in chemical terms literally – buffering acidity) extract also conduces to vinous longevity, then 2017 will be that vintage. One interesting by-product of 2017’s at times startlingly high levels of dry extract (as further explained in my vintage preview) is that a given must weight (which Germans measure in degrees Oechsle) translated into less fermentable sugar and thus lower eventual alcohol than would normally be the case. So on top of a welcome trend toward keeping must weights out of the red zone of potential alcohol, many growers, guided by whatever they deem ideal Oechsle readings at which to harvest, ended up surprised by lower-than-anticipated alcohol in their finished wines. The combination of high acidity, high extract and complete ripeness – not to mention the impression of energy conveyed by so many of the young vintage 2017s – makes them tempting for cellaring, and I suspect that Riesling lovers will not be disappointed. In the six months over which I have been making early assessments, I am already delighted by the extent to which many of the young 2017s have developed an appealing textural patina without losing their insistent sense of animating acidity.

In the least favorable instances, 2017 resulted in angular or rough-hewn Rieslings at the dry end of the flavor spectrum, and over-the-top botrytis influence among sweet wines. At certain less-fortunate addresses, especially on the Mosel, there is a sharp divide between wines noticeably but not entirely nobly tainted by botrytis and ones that taste as if fruit had been prematurely rushed to the press house in justifiable fear that botrytis was gaining the upper hand. But you would scarcely guess any of that if you began your exploration of this Riesling vintage in the Pfalz. And that is what I propose.

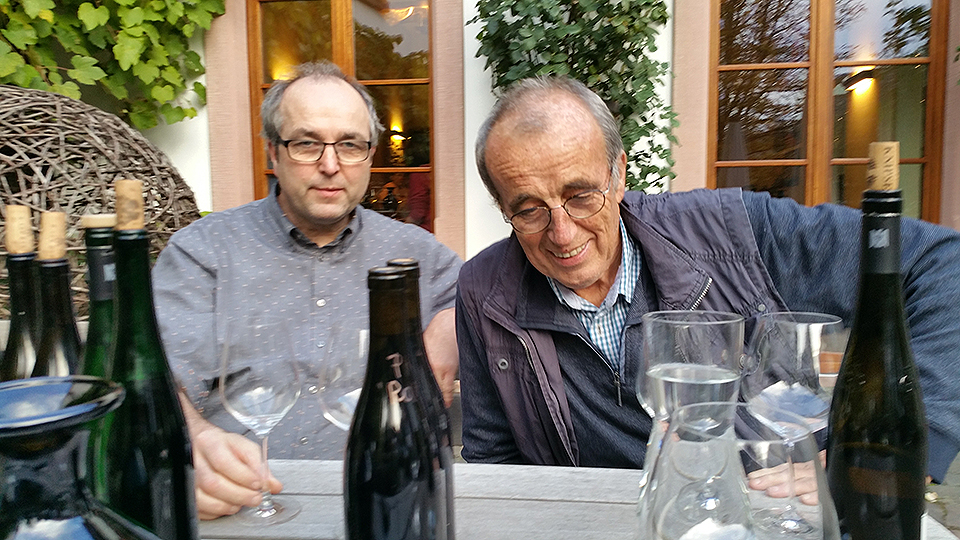

Hans-Günter Schwarz (seen savoring a von Winning cuvée he inspired) remains a mentor and father figure to countless Pfalz winegrowers. By my count, principals at half of the 20 estates profiled in this report began their careers under his tutelage, internalizing the motto “activism in the vineyard – minimalism in the cellar.”

Felicitous Pfälzer

The Pfalz enjoyed considerable luck in 2017. For starters, frost damage was generally confined to lower-elevation vineyards and the top slopes were only grazed here and there. What’s more, despite this region’s justified reputation for warmth and cloudless skies, in 2017 it recorded more summer rainfall than did many other German Riesling-growing regions. Yet mid-September’s rainfall prompted few outbreaks of botrytis – and not just because only two or three weeks separated mid-September from the completion of harvest. Even in instances where parcels were left hanging into October or even beyond, the grapes remained healthy. “We would have liked to harvest some nobly sweet Riesling,” observed Gunter Hauch of Bassermann-Jordan, “but there just wasn’t any botrytis thanks to conditions having been dry, dry, dry” – by which he was referring to conditions in the several weeks that preceded harvest and those after mid-September. (True, Müller-Catoir harvested TBAs at stratospheric must weights, but those were from Rieslaner, which will eventually shrivel even when there is no botrytis.)

It may not be coincidental to its success in 2017 that the Pfalz – which tends to enjoy relatively balmy conditions under a rain shadow – also features Germany’s highest concentration of organic and biodynamic growers. (The same conditions prevail in that neighboring hotbed of biodynamics, Alsace.) Most biodynamic practitioners insist that they achieve riper flavors at lower must weights than their non-biodynamic colleagues can. Whether or not one buys into the theory behind biodynamic practices or even believes that Rudolf Steiner’s agricultural musings deserve to be called “theories,” those practices certainly demand heightened attentiveness to the state of one’s vines, along with the encouragement of a vineyard environment that promotes self-sufficiency. And watchfulness as well as sustainability take on increasing importance in an era of perilous climatic evolution. You will be hard-pressed to find many people, even among skeptical growers and experienced Riesling-loving consumers, who believe that Bürklin-Wolf’s emergence and 21st-century status as a qualitative standard-bearer, or the rapid reemergence of Von Buhl as a source of profound Riesling, are not causally related to adoption of a biodynamic regimen.

“In hindsight,” claimed Mathieu Kauffmann of Von Buhl, “we didn’t begin harvesting one day too early. On the contrary, it might even have been beneficial if we had started sooner.” And as his co-director Richard Grosche observed: “On the day that we finished picking in 2017 – September 28 – we hadn’t even gotten started in 2013.” A great many growers offered variations on this thought: “The quicker the better, it’s just that three [or four] weeks is the fastest we can complete picking, even when working nonstop.” The existence this year of so many deliciously overachieving entry-level Pfalz bottlings seems to fit such an account. Harvesting for lower-echelon bottlings appears not to have involved any significant qualitative compromise, and even in the numerous instances where an estate’s Gutsriesling largely reflects early pickings, these wines also seem to display nearly ideal ripeness and acid balance, something that cannot be said of their counterparts from several other German Riesling-growing regions. At Von Winning, Riesling harvest began in earnest only after the September rain, and in tasting the resulting wines, legendary ex-Müller-Catoir cellarmaster Hans-Günter Schwarz, who is a conspicuous mentor to the Von Winning team, seemed to express an opinion opposite to that of Kauffmann. “Waiting to harvest was exactly right,” Schwarz opined. “Those cool nights at the end of September and early October were critical for creating fruit and aromatics.” The two views are not irreconcilable: both estates harvested many of their top sites in the fourth week of September. And both have some of the finest wines of their past four or more decades to show for it.

Despite his down-to-earth air of self-depreciation, Werner Knipser has been defying odds for most of his 71 years, not only rendering exciting Rieslings from northern Pfalz sites once thought second rate, but crafting some of Germany’s finest Pinots and pioneering with Rhône varieties. (Brother Volker, at left, typically plays front-man at the estate.)

Welcome Trends…

As mentioned already in this introduction – and discussed in detail in many of my recent reports – Pfalz growers are increasingly opting to pick at slightly lower must weights, mindful of Riesling’s sensitivity to alcohol and recognizing (even if it took more than a decade of conspicuous climatic warming and alcoholic warmth in wine to prompt this) that moderation should be considered a cardinal virtue in Riesling or Pinot Blanc Grosse Gewächse. This tendency is part of a widely self-proclaimed search for greater vinous finesse, which also extends to conservation of acidity, respect for the role of lees, and attentiveness to a great many imponderable and unquantifiable yet ultimately tasteable elements of wine.

Another recent stylistic development among leading Pfalz winegrowers – and one I view favorably, albeit with amusement – is an acceptance that Rieslings of unapologetic sweetness and consequent low alcohol have their place. When Hansjörg Rebholz – consummate vintner, chairman of the Pfalz VDP, and long-time defender of dryness in local Riesling – essays an unapologetically sweet Kabinett, you know that this category is enjoying a certain vogue, and unsurprisingly, other Südpfalz growers are following suit. (The earlier efforts of Keller and Schätzel in Rheinhessen have no doubt played an inspirational role.) Certainly, many of the steep vineyards in the Südpfalz routinely yield musts whose acidities are closer to those of the Mosel than to those of the nearby Mittelhaardt. And there are some Südpfalz growers, such as Messmer and Minges, who have never deserted residually sweet Riesling. If only more Pfalz growers could be persuaded of the many virtues possessed by Rieslings of “hidden sweetness”! (One dare not breathe the word halbtrocken in any of their company.)

One area in which recent viticultural evolution and quality-consciousness at leading Pfalz estates has both positive and problematic aspects is in the increasing return to and renewal of casks. A consequence has been a directly detectable influence of new or new-ish oak in young Rieslings. But tolerance for experiments with different capacities and sources of cask should pay long-term dividends. And at least in that majority of cases where new wood is entering cellars largely in the form of traditional Stückfässer or Doppelstückfässer (i.e., casks of 1,200- and 2,400-liter capacity), the casks in question are there for the long haul, and direct taste influence from wood will thus gradually disappear – in fact, the signs of that are already evident. Had traditional casks not been so widely abused or abandoned in favor of stainless steel, as many Pfalz proprietors and oenologists will remind you, then it would never have been necessary to introduce whole regiments of new ones at once. As for vintners like Stephan Attmann at Von Winning who favor 600-liter barrels for Riesling and are keen to regularly renew them, an oaky aromatic and tasteable element will always be present, and oenophiles will have to make up their own minds whether they find it appropriate and well-integrated. (My enthusiastic notes testify to an affirmative answer.)

Thanks to the late 20th and early 21st century revivals at Bassermann-Jordan, von Buhl, Bürklin-Wolf and von Winning, as well as at such less-famous estates as Acham-Magin, Georg Mosbacher and Werlé Erben, the basalt-based vineyards of Forst once again render Rieslings concomitant with their centuries-old renown. Here, the tiniest and internationally least-known of Forst’s five top sites, Freundstück.

…or Merely Pfalz Fashion?

One can hardly think “cask” without appending the word “maturation,” and one of the most far-reaching and dramatic recent developments in Riesling élevage is the decision by numerous leading Pfalz vintners to defer bottling until a new harvest is imminent, or even until after a second winter in cask or tank. The most conspicuous examples of this – discussed in my latest introductions to coverage of those estates – are Bürklin-Wolf and Von Buhl, but Von Winning is now following close on their heels. Hand-in-hand with this development is a related but separate delay in putting top wines on the market. (That has long been the case at Koehler-Ruprecht, but not until recently at any other leading Pfalz estate.) The importance for many estates of showing their young Grosse Gewächse at the VDP’s annual end-of-August or early-September public tastings was long cited as a factor inhibiting measured and leisurely élevage and release. But it is turning out not to be an impediment – or at least, not for estates whose wines enjoy brisk demand. The VDP has dropped a former prohibition on showing cask or tank samples at these Grosses Gewächs tastings; some estates, like Bürklin-Wolf and Von Buhl, simply present their Grosse Gewächse from the vintage preceding the one most of their colleagues are showcasing (Pinot Noir Grosse Gewächse have always been one vintage behind Rieslings at these events); and a few estates are simply taking some or most of their Grosse Gewächse out of the show circuit.

A lot could be said not only in favor of the luxury to choose a bottling and release date deemed optimum for one’s wine, but also in favor, generally speaking, of letting Riesling enjoy more time in bottle. That said, pioneering German wine importer Terry Theise is right to point out that the recent trend toward delayed bottling and release – which has accelerated in Austria thanks to a group decision by members of the country’s Traditionsweingüter – looks to become a fashion, and as such conducive to ignoring the message in one’s cask or bottle in favor of the calendar on one’s wall. And not merely a fashion, because, as Theise also rightly points out, it easily becomes a dubious marketing strategy simplistically suggesting that longer time before bottling or later release is a sign of higher quality. Not every site, vintage, or cellar regimen is equally conducive to delayed bottling or release, and if the wine – as opposed to fashion or marketing considerations – gets to have the last word with a grower, he or she might well abandon any attempt to bottle or release according to a strict calendar. But all of this having been noted, I can testify that tasting and discussing the vintage 2017 Bürklin-Wolf Grosse Gewächse with cellarmaster Nicola Libelli 14 months after the grapes were harvested, I concurred that a few further months before bottling would pay yet greater dividends. (Libelli also showed me some convincing instances of the same wine given different lengths of élevage.) At that address, I don’t think fashion or marketing is calling the shots, or that the wrong call is being made.

One last prominent Pfalz trend that risks becoming a fashion and a deceptive marketing tool is that the dry wines are becoming ever drier, analytically speaking. When Mathieu Kauffmann introduced a regimen of absolute dryness at Von Buhl, this trend was accelerated Pfalz-wide. “Lower is better” is not a wise slogan for Riesling, not should any grower convince him- or herself that optimum expressiveness can be achieved by attending to a wine’s analysis. Nevertheless, Kauffmann’s dry Rieslings – like those of Peter Jakob Kühn in the Rheingau – refute deliciously and decisively a long-held belief that at least a few grams of residual sugar are essential for achieving a truly grand dry Riesling. Of course, not just coincidentally, Kauffmann and Kühn are also demonstrating that a long-standing fear of malolactic transformation among Riesling growers is similarly unfounded. The positive upshot of these developments is a greater appreciation of Riesling’s versatility and a consumer base becoming attuned to an ever-wider flavor bandwidth. (Now, if only – to repeat myself – this would extend to an appreciation of Rieslings that harbor “hidden sweetness”!)

Given its location in an eponymous vineyard that is the Mittelhaardt’s highest, it’s unsurprising that Weingut Odinstal often seems to be in the clouds. But vineyard manager-cellarmaster Andreas Schumann’s head certainly isn’t. A go-to among biodynamic practitioners worldwide, he achieves uniquely delicious and intriguing results from this exceptional site.

Ominous Viticultural Horizons

The Pfalz being Germany’s warmest and driest Riesling-growing region, it isn’t surprising that worries about a changing climate are especially acute here. And unfortunately, those concerns range well beyond how to achieve ripeness while restraining grape sugar, or how to strategize one’s harvest within an ever-narrowing window. Even in the cooler Südpfalz, where progressively earlier harvests are less problematic, growers are voicing concern for the state of local aquifers. “That’s something that until the last decade, nobody in Birkweiler even gave a thought to,” said Franz Wehrheim, who has installed drip lines to irrigate his youngest vines until they reach a root depth where they can be dry-farmed, just as all Pfalz vineyards have traditionally been (and indeed, like those elsewhere in Germany, until recently, were required to be). The long-term as well as immediate effects of drip irrigation will become an increasingly lively topic of conversation among German Riesling growers, many of whom profess not to have been convinced by three decades of seemingly successful results in Austria. But a more pressing and heated topic of conversation will be where to get water from.

Climate change is also gradually and uncomfortably impinging on the traditional schedules of public tastings, auctions, communal wine fairs and wine journalists. This report is based on visits with 20 Pfalz growers, all but two of which were deferred until mid-November of 2018 because my usual window for tasting coincided with harvest. (Many winemakers in Austria as well as the Pfalz had to drop everything in the midst of harvest in order to make cameo appearances at scheduled release tastings or auctions that take place in September.) My on-site tastings were supplemented by selective stateside re-tasting in early 2019, as well by canvassing of a few wines from two other Pfalz estates.

Following usual Vinous practice, scores on those few wines that I have not tasted since they were bottled are expressed in parentheses as point ranges. Wines I rated 86 points or lower are frequently alluded to but generally not accorded a tasting note. I make exceptions to that rule for wines I still deem good values, or if I think a tasting note will demonstrate some important point (which might be that I think the wine in question is routinely overrated, or perhaps that its latest, disappointing performance requires special explanation). Details regarding the conventions of nomenclature and scoring that I follow in my reports, including an explanation of when and why I reference A.P. (official registration) numbers, can be found in the introductions to my reports on vintage 2015 and 2014 German Rieslings, the first to have appeared at Vinous.

You Might Also Enjoy

Vintages of Paradox & Mystery: A Preview of 2018 and 2017 in Germany and Austria, David Schildknecht, January 2019

Rheingau and Mittelrhein Riesling 2016: Stress Test, David Schildknecht, July 2018

Pfalz Riesling 2016: Restraint Rewarded, David Schildknecht, June 2018

Advantage Nahe: 2016 Riesling Excellence, David Schildknecht, April 2018

Saar & Ruwer: Beauties Despite a Bumpy 2016, David Schildknecht, April 2018

Saar and Ruwer 2015: Rain in the Nick of Time, David Schildknecht, May 2017

2014 Germany: Riesling Resists Rain on the Rhine, David Schildknecht, May 2016

Show all the wines (sorted by score)

- Acham-Magin

- A. Christmann

- Bassermann-Jordan

- Bernd Philippi - Kallstadter Saumagen GbR

- Dr. Bürklin-Wolf

- Dr. Wehrheim

- Georg Mosbacher

- Gies-Düppel

- Jürgen Leiner

- Klein

- Knipser

- Koehler-Ruprecht

- Messmer

- Müller-Catoir

- Odinstal

- Ökonomierat Rebholz

- Pfeffingen

- Pflüger

- Reichsrat von Buhl

- Theo Minges

- Von Winning

- Weegmüller

- Werlé Erben Forster Schlössel