Browse using the new Vinous website now. Launch →

Printed by, and for the sole use of . All rights reserved © 2015 Vinous Media

The Wines of Lazio: There’s Potential Gold in Those Hills

BY IAN D’AGATA I AUGUST 22, 2017

There is no Italian wine region that frustrates me more than Lazio (Latium in Latin), an area I know especially well, as it’s where I have spent the majority of my adult life. I say it’s frustrating because, hard as it may be to believe, there is perhaps no other lesser-known wine region in Italy that has more potential for fine winemaking than does Lazio and yet so much of that potential remains unrealized. Lazio is uniquely suited to viticulture because of its mild climate, rich and varied geological mix of soils (among which volcanic soils are prominent), marine breezes, adequate rainfall, pronounced day-night temperature variation and a plethora of rare, high-quality native grape varieties.

These extraordinary gifts should allow the region to make wines that can easily play on the world stage. And yet, for most of the 20th century, the region remained in the doldrums. One need look no farther than the Frascati denomination, a once-proud name, that is now in shambles. The good news is that, like elsewhere in Italy, the new generation that is in the process of assuming the helm of family estates throughout the region appears to be finally moving in the right direction.

The rugged beauty of the Piglio DOCG area

History Repeating, at Long Last

Two millennia of quality viticulture and a history of much sought-after wines (at least throughout antiquity and medieval times) attest to the level of quality of wines that was once the norm in Lazio. In ancient Rome, dozens of different wines were sold (many made in the immediate surroundings of Rome), wine bars were popular, and wine tasters – the haustores – were held in great esteem. Horace, Martial, Petronius and other famous authors wrote and argued about wines, much as is the case today, and Pliny, the consummate cataloguer, even ranked what he thought were the best.

Lazio’s wines generated great enthusiasm in later centuries as well: in the 1500s Pope Paul III had his own personal sommelier (bottigliere, as the position was called) and a very well stocked cellar, one in which the wines of Lazio were strongly represented (it appears that the Pope most appreciated the white and red wines of the Colli Albani, as well as those of Castelgandolfo). Later on, Queen Victoria was known to be a big fan of Frascati and asked for it to be served at court.

But early success eventually hurt quality wine production. Producers began thinking in terms of quantity rather than quality, and advances in modern viticultural and winemaking techniques – reduction of yields, better clonal and massale selections, organic farming, controlled fermentation, more hygienic cellars, and the use of new and better wood, among other measures – that were implemented all over Italy in the latter decades of the 20th century passed Lazio by. This state of affairs became unsustainable when quality wine production became the standard everywhere in the 1970s; the market dried up for Lazio’s many insipid white wines that oxidized soon after bottling, as well as for its rustic reds.

While viticulture and winemaking were greatly improved in the 1980s and ‘90s, many of the same mistakes were made as in other parts of Italy where quality wine production was starting up again. For example, while Merlot and Cabernet Sauvignon were long grown in Lazio (at least since the mid-18th century: Pasquale Visocchi was the first to plant such vines in southern Lazio, and the Cabernet wines of Atina quickly became famous), other varieties like Syrah, Chardonnay, Petit Verdot and Sauvignon Blanc have no such historical pedigree in Lazio and were planted only in recent times by people easily swayed by internationally minded consultants looking for a quick fix. The result was that precious time was lost on making, for example, Chardonnay and Sauvignon Blanc wines of absolutely no interest whatsoever (especially when compared to much better and often less expensive wines made elsewhere in the world with the same varieties) when instead that time and energy could have been used to study the local native grapes, some of which are of extremely high quality. If only a little more care and attention had been paid to varieties such as Bellone and the Cesanese cultivars, Lazio wouldn’t find itself so far behind today.

But today the scenario is no longer so bleak. In fact, some of Lazio’s wines already rank among Italy’s least-known but best examples. You might say that we now find ourselves on the brink of rediscovering the true greatness of wines that were once much sought after by the denizens of ancient Rome and throughout the Roman Empire.

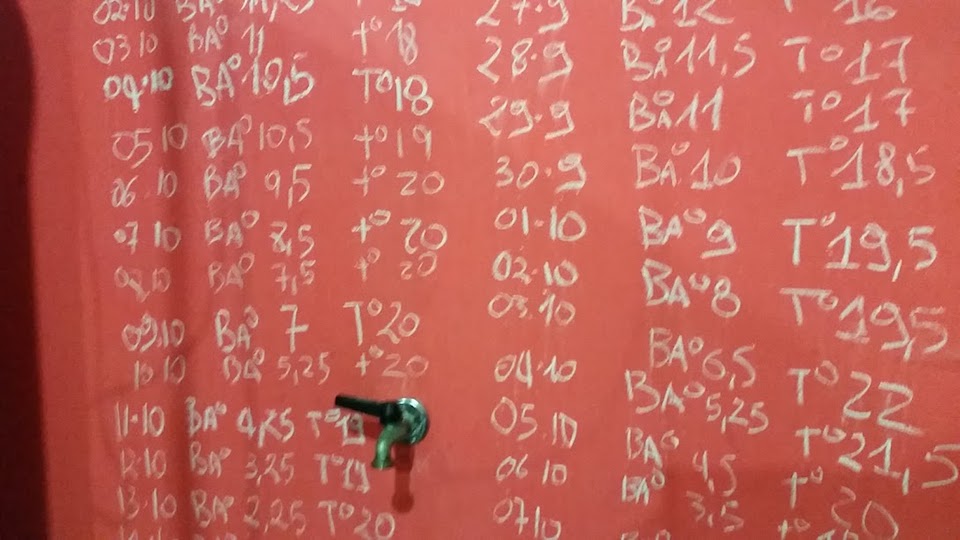

The writing's on the wall at the Costa Graia estate (decreasing sugar levels and temperatures of a specific vat in the cellar)

The Wine Grapes of Lazio

While international grape varieties such as Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot have been grown in Rome and Lazio at least since the 1700s, and with outstanding results (for example, the Fiorano Rosso wine made by Ludovisi Boncompagni just outside Rome back in the 1960s and ‘70s was often in the same quality league as Sassicaia or Solaia), no other wine-producing region of Italy, with the possible exceptions of Campania, Friuli Venezia Giulia, Sardinia and Piedmont, has Lazio's diversity of native grape varieties. Little-known and almost forgotten cultivars such as Malvasia del Lazio, Bellone, Trebbiano Giallo (now very rare), Roscetto, the three Cesanese varieties, and Nero Buono di Cori are now being studied and planted extensively, giving rise to some excellent and distinctive wines. Moreover, Lazio also boasts important plantings of other varieties that are found in only a few other Italian regions (such as Bombino Bianco, Grechetto di Orvieto and Grechetto di Todi, Passerina and Olivella), but the jury is still out on the issue of whether these are exactly the same varieties as those growing elsewhere in Italy or are homonyms—i.e., grape varieties that share similar names but are in fact completely different cultivars.

Of the white grape varieties of Lazio, Malvasia del Lazio (also known as Malvasia Puntinata) stands out. A member of the large Malvasia group (there are at least 17 different kinds all over Italy, only four of which are related), it is grown especially in the Castelli Romani area but is found in small pockets throughout the region. Unquestionably a great wine grape, it can give delightful dry, fresh white wines with a lightly aromatic character as well as some of Italy’s very best botrytis-affected sweet wines. There’s another cultivar bearing the Malvasia moniker in Lazio: Malvasia Bianca di Candia (not to be confused with Malvasia di Candia Aromatica, which is aromatic and typical of the Emilia region). Although not a native of Lazio, Malvasia Bianca di Candia was extensively planted in the mid-20th century along with another non-native variety, Trebbiano Toscano. Both of these grapes are characterized by high productivity and resistance to disease, and so, logically enough, farmers planted them everywhere. Unfortunately, they make dry wines that are (at best) insipid and boring and, along with other factors, gave Lazio’s wines a bad name through much of the 20th century.

Bellone is potentially one of Italy’s greatest white wine grapes. Every time I show someone a well-made Bellone wine, they come away smitten with the grape and the experience. High in total acidity (Bellone can also be used to make delightful sparkling and memorable sweet wines), its wines offer hints of tropical and ripe citrus fruits and wild herbs. Bombino is another white variety of uncommon potential, as some of the better examples from Puglia are also demonstrating. Like Bellone, Bombino was historically a small part of the traditional blend of Frascati and other Castelli Romani wines but fell by the wayside while producers were busy churning out volumes of pointless wines made with essentially third-rate varieties. A late ripener – hence the lack of enthusiasm for it by growers who are not inclined to risk leaving their grapes hanging in bad weather – Bombino Bianco can give flavorful, saline wines characterized by bright acidity.

The Grechetto varieties are most often associated with Umbria but are grown in Lazio as well (in fact, a small portion of the Orvieto production zone spills over into Lazio), especially in the regions where it borders Umbria and Tuscany. These wines typically offer aromas and flavors of flowers and herbs, complicated by quince, tropical fruits and hazelnut – especially in more concentrated wines made with riper grapes – and with fine acidity and noteworthy tannic bite, in true Greco style.

There are fewer native red grapes in Lazio, but the Cesanese varieties are unquestionably capable, in competent hands, of giving very fine, perfumed, penetrating red wines. I don’t mean to overstate my case, but I truly believe that the Cesaneses are capable of producing wines that one day might be viewed in the same light as those made with Nebbiolo or Aglianico. There are two different Cesanese varieties, Cesanese Comune (more common in the Olevano Romano area) and Cesanese d’Affile (more commonly planted in the areas of Piglio and Affile). A third cultivar, Cesanese Nostrano, has only recently resurfaced, and the jury is still out on its ultimate potential. Any way you slice it, the Cesaneses are difficult varieties to work with: they are reductive varieties, so off aromas can be a problem, and they are also late ripeners and thus often fail to reach optimal phenolic maturity in cool years. For these reasons, their tremendous potential was not recognized until recently. Today, Cesanese wines are by a wide margin the best of Lazio, and some of them already rival the more famous reds of more fashionable wine areas of Italy.

Finally, Nero Buono, typical of the area around Cori, is a red grape variety that yields pleasant wines with dark color and heady perfume, but I suspect that it could give a great deal more.

Vineyards at the Colacicchi estate

The Wine Production Zones of Lazio

There are 27 DOC (Denominazione di Origine Controllata) and 3 DOCG areas in Lazio, some more famous, some less. What is undeniable is that all of them are making better wine today than they were a generation ago and progress seems likely to continue. While some areas lag behind others, even high-volume production areas are now turning out fresh, well-made wines that avoid the flaws that were once common. Historically, Lazio always made more white wine than red, and that is still the case today (the breakdown is roughly 70/30 in favor of white wines). But red wine production is increasing steadily every year. In 2015, 56% of the white wines made in Lazio and 37% of the reds were DOC wines, but that qualification means very little in and of itself and so cannot be taken as an indicator of a region’s overall wine quality.

Proceeding north to south, the wine-producing areas of Lazio are the Viterbo and Rieti provinces in the northern part of the region (roughly 12% of Lazio’s surface under vine, according to 2015 data); Rome and its surroundings, where the once famous Castelli Romani and the up-and-coming Cori area are located (roughly 57% of Lazio’s vineyard acreage); the Frusinate area in the south-east (10%); and the southern or coastal section in the province of Latina (21%).

Of Lazio’s many DOCs and DOCGs, several stand out in importance. The northern sector includes some well-known DOCs, first and foremost that of Est! Est!! Est!!! di Montefiascone, as well as Aleatico di Gradoli (like the Est! Est!! Est!!! DOC, it is also located around the beautiful Bolsena lake, but on the lake’s northwestern shores; the zone produces unique lightly sweet, aromatic red wines that offer very good value) and the small portion of Orvieto that falls within the borders of Lazio.

The Castelli Romani is the biggest and most famous wine-producing zone of Lazio, characterized by charming little towns situated in a semicircle around Rome (and so-named because each one boasts at least one major noble residence or palace). The most famous are Frascati (Frascati Superiore and Frascati Cannellino, the latter a sweet wine, are two of Lazio’s three DOCGs), Marino and Velletri. Although similar, the wines of these little towns and their surrounding areas differ somewhat: the wines of Frascati are renowned for their fragrance, those of Marino for their intensity and roundness, and those of Velletri for their elegance and balance (the latter is the only town more famous for red wines than whites, an anomaly of sorts in Lazio’s vinous panorama). Farther south, the city of Cori and its surroundings are especially promising: producers like Marco Carpineti and the Cincinnato co-op are making some of Italy’s most interesting and fairly priced wines.

The coastal section of Lazio is most notable for its Moscato wines (made with the local, unique Moscato di Terracina grape variety, different from Moscato Bianco or Moscato di Alessandria, the latter more commonly called Zibibbo in Italy), although some delicious easy-drinking reds are also being made. Still in the southern part of Lazio but farther east is the Frusinate area, where one DOCG, Cesanese del Piglio, and two DOCs, Cesanese d'Affile and Cesanese di Olevano Romano, are making not only the region’s best red wines but some of the most exciting in Italy. Finally, Atina, at the southernmost tip of Lazio, is where some spectacular Cabernet Sauvignon-based wines have long been made but have recently fallen on harder times. Any return to prominence will be difficult if the average price per bottle remains as low as it is today, which makes it harder for winemaking families to invest in, and improve, their equipment and holdings.

Spoils of war, or tasting Lazio wines during a cellar visit

Recent Vintages

The 2016 vintage looks to be very promising in Lazio, having produced white and red wines with above-average perfume. The 2015 vintage was warm throughout the growth cycle and so the early-ripening varieties yielded broad wines that will mature quickly. Some wines show an element of greenness typical of incomplete phenolic maturity but there are also numerous luscious, round, rich reds that are very easy to like for their fleshy opulence. Both 2013 (cool, uneven weather) and 2014 (cool and very rainy) were more challenging years, especially 2014, which like everywhere else in Italy was marred by persistent rainfall throughout most of the growth cycle and the fall.

The wines reviewed in this article were tasted during estate visits in May, June and July, with additional tastings at my office in Rome.

You Might Also Enjoy

Harnessing the Potential of Soave, Ian D’Agata, June 2017

Abruzzo & Molise: This Year It’s Reds Over Whites, Ian D’Agata, June 2017

Ronchi di Cialla's Schioppettino di Cialla: 1982-2010, Ian D’Agata, June 2017

2016: A Very Good Year for Italy’s Many Rosatos, Ian D’Agata, May 2017

Amarone: New Releases, Ian D’Agata, May 2017

The Wines of Basilicata: Paradise Lost and Regained, Ian D’Agata, April 2017

Show all the wines (sorted by score)

- Alberto Giacobbe

- Borgo del Cedro

- Casale Certosa

- Casale del Giglio

- Casale della Ioria

- Castel De Paolis

- Cincinnato

- Colacicchi

- Colline di Affile

- Costa Graia

- Damiano Ciolli

- Fontana Candida

- La Visciola

- Marco Carpineti

- Paolo e Noemia D’Amico

- Principe Pallavicini

- San Giovenale

- Santa Lucia

- Sant’Andrea

- Sergio Mottura

- Tenuta di Fiorano/Principe Alessandrojacopo Ludovisi Boncompagni

- Terenzi

- Trappolini