Browse using the new Vinous website now. Launch →

Printed by, and for the sole use of . All rights reserved © 2015 Vinous Media

Book Excerpt: Appellation Napa Valley – Stags Leap District

RICHARD MENDELSON I JULY 25, 2017

In the early 1970s, neighbors Warren Winiarski and Carl Doumani were the Hatfields and the McCoys of Napa Valley. Their legal wranglings, all of which concerned the rights to the Stags Leap name in its various spellings – Stag’s, Stags’, and Stags – are legendary. Each named his new winery after the historic cliffs known as the Stags Leap Palisades that lay to the east of their properties. In early 1970, Winiarski began producing and selling grapes and later making wine under the name Stag’s Leap Vineyards and Wine Cellars. Doumani around the same time formed a limited partnership, Stag’s Leap Associates, that used the names Stag’s Leap Ranch and Stag’s Leap Winery. Warren and Carl battled over the Stags Leap name and the apostrophe for more than a decade. When their vintner and grower neighbors later joined the fray by filing a petition to establish the Stags Leap AVA without any apostrophe, the name dispute between the two men turned into an epic neighborhood battle. Winiarski and Doumani were men of very different backgrounds.

Winiarski grew up in Chicago. Winiarski means “winemaker” in Polish, and Warren’s father, in fact, did make dandelion and fruit wine, and even mead, in his spare time. Warren recalls putting his ear to the barrels to listen to the fermentation, and on special occasions he would be allowed to taste the wine. But Warren was drawn to a different calling – academia – at least at first. After graduating from St. John’s College, he pursued graduate studies in political philosophy at the University of Chicago. After two years there, he moved to Italy to conduct research on Machiavelli. In that foreign environment and at that time of his life, wine, grapegrowing, and the culture of wine stirred his passion. Although he returned to Chicago to teach at the University College for six years, his interest in a life outside the city, devoted to grapes and wine, never waned.

In 1964, Warren decided to leave Chicago. He moved to Napa Valley to work as the assistant winemaker at Souverain Cellars, and he stayed there for two years and two crushes. After that, his rise in the world of wine was meteoric. In 1966 he was hired as a winemaker at Robert Mondavi’s newly opened winery in Oakville, and he stayed there for two years, deepening his understanding of grapegrowing and winemaking. By then he was ready to strike out on his own. As Warren stated in his oral history, “After two two-year cycles, one having to do with what you might call a village art as practiced by Lee Stewart (at Souverain) and the other with a high technology component as at Robert Mondavi, I thought I had seen both poles of the possibilities for the industry…. I thought it was time to move on.”

Warren bought his own vineyard on Howell Mountain, consulted for other wineries, and served as an itinerant winemaker. In 1969, he had the good fortune to meet winegrowing pioneer Nathan Fay, who was the first person to plant Cabernet Sauvignon beneath the Stags Leap Palisades. Warren wanted to learn about Nate’s new irrigation technique, but he also relished the opportunity to taste Nate’s homemade 1968 Cabernet Sauvignon wine. That wine was so gorgeous that it fulfilled everything Warren was looking for in a California Cabernet. Warren still waxes eloquent about that wine 45 years later. To him, this was a wine that “went to the limit, the most beautiful expression, inspirational, with perfect structure, wonderful perfume, and moderate alcohol, just like Nate himself who was a man of moderation.” The next year, Warren purchased the vineyard next door to Nate and his wife Nellie, and the rest is history. A short four years later, Warren made the 1973 S.L.V. Cabernet Sauvignon from that very vineyard. In 1976, that wine won the Paris Tasting, which would soon be recognized as a landmark event in the history of American wine. This singular event sealed Warren’s reputation in the world of wine. It also increased the value of the land around his and, ironically, set up one of the most celebrated battles in Napa Valley history, a battle that eventually hinged on a lone apostrophe.

Carl Doumani took a different route to the Napa Valley. He was living in Los Angeles, where he invested in and developed restaurants and real estate. But in 1968, on a trip to Napa Valley, Carl met Jack and Jamie Davies of Schramsberg, and he shared some of their sparkling wine. Carl had so much fun that he decided to look for a small property in the valley where he could build a cabin for family getaways. But that modest search soon turned into something far more grandiose. One day in 1970, his real estate agent showed him an historic 400-acre property located below the Stags Leap Palisades, a piece of land once owned by Horace Chase, a Chicago financier. Carl was immediately captivated, and in June of 1970 he purchased it.

Chase had built a wonderful stone manor house on the property in 1892 for his wife Minnie Mizner, but it had been long since abandoned. That manor house, Carl soon learned, had a colorful, but checkered, history. Over the years it had been used in a variety of unusual ways by different owners: as a resort, a post office, and a rest facility for naval officers at Mare Island. There are lots of unsubstantiated stories, too, about mob connections, a speakeasy, a brothel, and even a ghost in the manor house, the latter being a story I can’t resist recounting.

Frances Grange, widely known as “The Duchess,” owned the property after the Chases. According to legend, Grange was a world traveler and on one trip brought back with her from Egypt a mummy that she would bring out as a curiosity at parties in the manor house. When her daughter-in-law Amparo sold the property in 1954, the mummy was moved from the “go down” (a drive-through barn that the Granges used for storage) to an upstairs closet on the third floor of the manor house. Later, and perhaps inevitably, the new owner happened upon the mummy and was scared out of his wits. He immediately called the police, who in turn phoned Amparo’s children to inquire if they knew anything about the mummy. The kids revealed everything, and in a fitting tribute to their mother, donated the mummy to their local high school. The story made the news headlines and quickly became part of Napa Valley lore.

Whether that mummy’s spirit is the ghost of the manor house is unknown, but Carl, in any event, was undeterred. He restored the manor house and went into the wine business as Stag’s Leap Winery, with the same placement of the apostrophe as Warren’s Stag’s Leap Vineyards and Wine Cellars. Although not trained as a winemaker, he knew how to hire winemakers and run a business.

His staff also knew a thing or two about public relations. They relished the story about the ghost of the manor house and recounted the ghost sightings in the winery’s 2001 newsletter, under the title “A Ghost and a Mummy.” As the newsletter told it: Some have seen her. Robin Gonçalves (a winery employee) was a skeptic until she and her husband stayed in the Bees’ Bedroom of the manor house after attending a golf tournament at Silverado. He was shaving so she walked out into the hallway to use the other bathroom. Where the hallway jogs left, she met a woman who had just walked out of the wall and proceeded to pass right in front of her. Robin ran back to the bedroom, jumped under the covers and hid. She was frightened, but didn’t feel threatened….

After having spent the night in the Ghost’s Bedroom, fresh from sleep, Robert Brittan (the winery’s General Manager and Winemaker from 1988 to 2005) walked out into the upstairs hallway and saw her in the bright morning air. Kathy Nelson, eminence of all things administrative for Warren Winiarski winery and estate, feels sure there is a spirit here, and senses that she’s very kind. Her description is familiar, as if she were describing a long-lost sister, or an old friend.

Doumani’s purchase of the Chase estate made him a neighbor of Warren Winiarski, and in terms of temperament the two men could not have been more different. Warren was an intellectual with a stubborn streak; Carl was a maverick with a mischievous side. In the mid-1980s, for instance, Carl quit the NVV because it had become too political and, with Justin Meyer of Silver Oak, he founded the GONADS, the politically incorrect, irreverent, all-male Gastronomic Order of the Nonsensical and Dissipatory Society. Carl loved all-night poker games, expensive Cuban cigars, and Mezcal. Warren, by contrast, was a professor at heart and a relentless perfectionist with a taste for art and refinement. He was, in sum, a man who would not be caught dead in any organization called GONADS. Perhaps it was inevitable that the two men would one day clash.

Their legal jousting began back in 1972, when Doumani sued to stop Winiarski’s use of the name Stag’s Leap Vineyard—and lost. The following year, Winiarski sued Doumani, claiming exclusive rights to Stag’s Leap. Warren won in Napa County Superior Court in 1978, but that decision was overturned on appeal in 1982. The appellate court found that the name Stag’s Leap is geographical and that, prior to 1973 when Winiarski filed his lawsuit, it had not “acquired a secondary meaning by becoming primarily identified in the marketplace with a particular party’s goods, services or business.”

In 1978, while the litigation was still underway, Carl – or more accurately his Stags’ Leap Winery, Inc. – registered Stags’ Leap Vineyard as a word mark and Stags’ Leap as a design mark, both with the apostrophe following the “s.” In 1979, Warren petitioned to cancel those registrations, but that action was put on hold (in legal jargon, stayed) until the civil lawsuit concluded.

Warren and Carl proved to be a good match in court. Although generally courteous and affable, Warren used all the Machiavellian strategies he had learned at university in an effort to gain the upper hand in the litigation. Carl, for his part, was a trader, a born dealmaker, someone who would never be pinned down, and who always had a new angle to play. When locked in a battle, he didn’t mind walking away or fighting, whichever it took to secure the exclusive right to the Stag’s or Stags’ Leap name.

Despite their legal confrontations, Warren and Carl never lost sight of their common interests. In 1985, with Warren’s cancellation action against Carl’s trademark registrations still on hold, they joined together to fight off an intruder. Their neighbor, Gary Andrus of Pine Ridge Winery, was using Pine Ridge Stags Leap Vineyard and Stag’s Leap Cuvee on his labels. Stag’s Leap Cuvee was part of Pine Ridge’s Cuvee line of wines—Rutherford Cuvee, Oak Knoll Cuvee, and the like. Warren and Carl jointly filed a lawsuit against Pine Ridge to stop this infringement, but they didn’t succeed. The lawsuit settled out of court in 1985. Pine Ridge was allowed to continue to use Stags Leap without any apostrophe, without any image of a stag—standing, leaping, or otherwise—but not as part of its winery or brand name. At the same time Warren dismissed his trademark cancellation actions against Carl. When the dust settled, Warren had the apostrophe before the “s” (Stag’s Leap), Carl had it after the “s” (Stags’ Leap), and Gary Andrus of Pine Ridge had no apostrophe at all (Stags Leap).

In 1976, while Warren and Carl were still battling in court, Warren’s wine won the Judgment of Paris, and all of Stags Leap (the area) gained immediate international renown, along with Warren’s Stag’s Leap (the winery). In his winery’s promotional material, Warren proudly proclaimed, “Stag’s Leap is a regional designation which should in time become as familiar to wine buyers as certain domaines in European winegrowing regions.” Indeed it has, but that statement would return to haunt Warren.

THE FIRST DISTRICT

Warren's and Carl’s neighbors believed that Stag’s Leap and Stags’ Leap are brands and that Stags Leap is a place. After all, Stags Leap, without an apostrophe, is clearly featured on USGS maps. But I’m getting ahead of myself. Well before the AVA system was even established, neighbor Dick Steltzner had devised his own way to recognize the area as an appellation of origin.

Dick is a third generation Californian, born and raised in the San Francisco Bay Area. Like many early California families, the Steltzners had ties to farmland. Graduating from college with a Master’s Degree in Fine Arts, Dick moved to St. Helena and began throwing and selling pots at his shop on Lodi Lane. In 1964, he decided to change careers and return to his farming roots. His vineyard management business quickly flourished, and Dick established many notable vineyards, including Al Brounstein’s Diamond Creek Vineyard, Mike Robbins’ Spring Mountain vineyards, and Bernard Portet’s Clos du Val. By 1975, he was farming 450 acres in 22 separate locations.

Grapes were a natural for Dick because of his longtime interest in specialty crops grown in unique locations, particularly wild rice, kiwis, and blackberries. Dick loved appellations of origin because they allowed him to differentiate and promote his crops. But Dick, as an iconoclast, didn’t want to rely on the federal government, so he devised his own appellation system that would bypass ATF completely. Borrowing from his rice farming experience with irrigation districts, Dick wanted to create a new “special district” under California law to lead grapegrowing and winemaking in Stags Leap. Dick envisioned a confederation of properties, funded by tax assessments on the property owners who would set their own growing and winemaking standards.

Dick approached Carl Doumani, who was supportive, as were many other wineries in the area. Carl’s primary interest was to keep the district small and restrict it to growers of specific red varieties—Cabernet Sauvignon, the other red grape varieties of Bordeaux, and Carl’s favorite, Petite Sirah. To get the ball rolling, Dick started putting Stags Leap District on his wine labels, but he quickly realized that the district was an idea before its time. Dick wanted to exclude heavy soils from the district, but that type of line drawing would be contentious. Standard setting and varietal selection also were divisive, and self-taxation was unwelcome. Dick’s Stags Leap District never got off the ground.

THE PETITION

Following the failure of Dick’s district, he teamed up with John Shafer of Shafer Vineyards to establish a Stags Leap AVA. The two of them asked me in early 1985 to prepare the petition and help plot their strategy. Their goal was to establish the first truly small sub-AVA of Napa Valley—only 2,000 acres compared to the 14,000- acre Howell Mountain. At the time, I was living and working on the San Francisco peninsula as an international trade consultant with my former Stanford Law Professor John Barton. Although AVAs weren’t the focus of our consulting practice, John encouraged me to take on the project for one simple reason: he knew how much I loved wine and the Napa Valley. An AVA project, he reasoned, would supplement our partnership income and allow me to return to hallowed, familiar ground.

I knew John Shafer well; Marilyn and I had stayed at his guest home during the summer of 1981 when I clerked at Dickenson, Peatman & Fogarty while at law school. We were the guests of Nikko Schoch, who was then the winemaker at Shafer. Living under the gray cliffs of the Stags Leap Palisades was a special treat. But it also was the scene of a scary summer fire, set by an arsonist, which came within a few hundred feet of the Shafer’s newly constructed residence. We were all evacuated, Marilyn pregnant with our first child, Margot. The home was saved by setting a backfire on an unplanted, adjacent hillside. That field burned black, but vineyards don’t burn and, at fire’s end, they were still green. Seeing that, Elizabeth Shafer, who had resisted planting that hillside in vines, said to her husband John, “Plant that hill right now!” Nikko named it the Firebreak Vineyard, and it was the fruit source for Shafer’s Firebreak Sangiovese-Cabernet blend.

John assembled a committee of Stags Leap vintners and growers to fund and oversee the AVA project. The winery members were an illustrious group: Clos du Val, Pine Ridge Winery, Shafer Vineyards, Steltzner Vineyards, and two wineries that owned vineyards in the AVA but whose wineries were located elsewhere—Robert Mondavi Winery and Joseph Phelps Vineyards. The grower members included Napa Valley old-timers like Peter Candy, F.S. (Si) Foote, Ernie Ilsley, Angelo Regusci, Norman Robinson, Harry See, and Susan Vineyard. John, ever the statesman, was elected the chairman.

We knew at the outset that our proposed Stags Leap AVA would be controversial. It was by far the smallest, and the most geographically and viticulturally distinctive, of Napa Valley’s sub-appellations. Drawing those distinctions would not be easy. That type of detailed data on soils, climate, geography, geology, and the like generally did not exist. We would have to assemble precise scientific data to distinguish one vineyard from another. If ATF were true to precedent and could be persuaded relatively easily to expand any appellation, we would have to provide convincing, objective evidence in defense of our boundaries to prevail. That meant more homework and more scientific consultants and historical experts. The days of the quick and dirty appellation petition were over. Stags Leap would rewrite the rules of the game. Indeed, the court battle between Warren and Carl was only round one in what proved to be a multi-round affair.

We assembled a team of experts in geography, soil science, climate, and history. We did original field-based research to define the AVA boundaries and distinguish the terroir. We hired a physical geographer and ecologist, Professor Debbie Elliott-Fisk of UC Davis, who dug numerous soil pits throughout the AVA to examine firsthand the soil depth, texture, and profile. Bale loam soils predominate in Stags Leap, as the Soil Survey indicated, but Debbie showed that many of the soils in the area were misidentifed by the U.S. Soil Conservation Service. She also discovered in the gravelly alluvial soils, cemented at a depth of three to four feet, a layer of volcanic ash that has formed a duripan (a subsurface soil horizon of cemented silicate particles). That soil layer obstructs root growth and affects water and air movement through the soil, decreasing vine vigor and naturally reducing the canopy. As a result, the plant’s energy is directed to producing fruit with great concentration and flavor intensity.

I learned an important geomorphological term that perfectly describes and defines Stags Leap: “orography.” Orography is the scientific study of mountains and, more broadly, includes any elevated terrain. The distinctive orography of Stags Leap consists of the Vaca Mountains to the east and, to the west, hills that rise out of the valley floor, west of the Silverado Trail. These hills are a rarity in an otherwise flat valley, caused by faulting and uplifting that created the area’s unique bedrock islands. The resulting ring of mountains and hills serves as a topographic funnel, capturing and directing the cooling maritime breezes that travel north from San Francisco Bay. In the late afternoons, Stags Leap turns windy as the cool, moist air whips through the funnel.

In the preceding AVAs, the climatic evidence focused on the heat summation data and the classification of grapegrowing areas into regions ranging from Region I (the coolest) to Region V (the hottest). This works fairly well when the AVAs are large, but the data for this type of analysis is simply not available in so small an AVA as Stags Leap. The climatic distinctions would have to be much more refined to support the petitioners’ proposed boundary.

Our meteorologist had the foresight to install two automatic weather stations inside the AVA. Based in part on the data from those stations, he concluded that the wind flowing through the AVA as a result of the mountains and intervening hills lowers the temperature and increases the humidity inside Stags Leap.

We also had anecdotal evidence about Stags Leap’s unique climate. Bernard Portet of Clos du Val, near the southern end of the AVA and east of the Silverado Trail, was a vintner whose instincts the appellation committee could trust. His father André had been the régisseur (manager) at Château Lafite Rothschild in Bordeaux, where Bernard was born and raised. Bernard joined owner John Goelet as co-founder and winemaker of Clos du Val in 1972. But before he would start to make wine in the Napa Valley, Bernard had to find the best location for the new winery. He recalls “driving south down the [Silverado] Trail, from St. Helena, and my car’s air conditioning wasn’t working, so I had the windows open, and when I reached a certain point, I noticed that the temperature had changed; it was much cooler. And I knew this would be the place to make the wine I wanted to make. I knew it was a place where I could make a wine with more fresh fruit from the cooler weather.”

I myself observed many times that the fog traveling northward from San Francisco Bay would sit in the Stags Leap funnel and stop, proceeding no farther north. Then in the late afternoon, the winds from San Pablo Bay would pick up and whip through the area. And in the evening, all the sunshine that had struck the palisades in the daytime radiated from those rocks to warm the soil and the vines. Clearly, topography influenced climate, and this was all part of the complex matrix of the Stags Leap terroir.

For any AVA petition, ATF requires proof that the name is locally or nationally recognized. Our best evidence was right on the USGS map where Stags Leap was prominently displayed as the name of the palisades. We also uncovered a lot of local lore about the name. The story that I liked most is that a stag—some old-timers say it was a Roosevelt elk—jumped from the cliffs to avoid hunters who had trapped it on the ledges. No one knows for sure if the stag lived or died. Another story relates to Mr. William Staggs, who lived near the southern end of the AVA on a 72-acre ranch with a small vineyard. Might he have named the area and eliminated one “g” rather than fooling around with apostrophes? Perhaps most logically, the name may refer to the abundance of deer and elk in the area combined with “leap,” commonly used to describe British and North American place names.

ATF doesn’t list varietal specificity or wine character as one of its AVA criteria, but every member of our appellation committee knew that Stags Leap Cabernet Sauvignon wines have a unique fingerprint, a special goût de terroir. Warren Winiarski describes it as “a suppleness and a velvet quality at the edge of the wine, and under that softness it has structure and kind of a body, notwithstanding the robust quality in the middle of it…. It has been described as an iron fist in a velvet glove.” Wine writers Eleanor and Ray Heald distinguish Stags Leap Cabernets by their “pronounced cherry, blackberry, and black currant flavors and chocolate notes…a beautiful mid-palate structure and an elegant finish with finesse.” While we knew that we could not restrict the AVA to one grape variety, we planned to impress on ATF and the wine world the unique characteristics of the Stags Leap Cabernet Sauvignon grapes and wines.

Compared to the four-page petition for Carneros, the Stags Leap petition, filed in August 1985, ran 60 pages, plus another 150 pages of declarations and exhibits. It took nine months to prepare. All the while, I was commuting weekly from the San Francisco peninsula to Napa, a two-hour drive each way. On each trip, Dick Steltzner would invite me to spend the night in his family’s small, log-cabin home. Dick is an eclectic, generous, and lovable man—a farmer, artist, hunter, chef, winemaker, and raconteur. The evenings at the Steltzner home were always fun. I felt like the lawyer on Falcon Crest, a television serial of that era shot at Mike Robbins’ Spring Mountain Vineyard estate on the other side of the valley, west of St. Helena. The lawyer in that program was treated like family by the estate owners, a true consiglieri. The only difference was that the lawyer on Falcon Crest didn’t taste as many wines as I did—all in the name of research, of course!

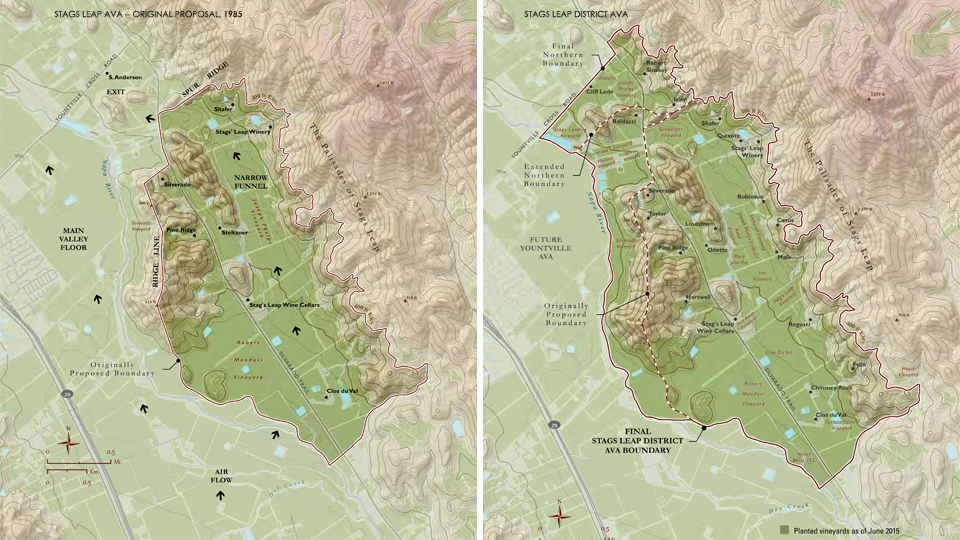

Stags Leap AVA original proposal in 1985 (left), Stags Leap AVA as finalized in January 1989 (right)

MODIFIERS AND APOSTROPHES

We knew that our use of Stags Leap as the AVA name was sure to raise the ire of both Warren and Carl. Warren adamantly opposed the petition. He believed that a Stags Leap AVA would confuse the trade and consumers. As he later stated, “It was my original belief that if the grapegrowers and vintners decided to propose a name for our distinctive area and its formal recognition, they should give it a name which would not confuse the public with our already existing proprietary name.”

Warren and Carl both feared, understandably, that their brands would be tarnished by any and every sub-par Stags Leap AVA wine because the consumer wouldn’t be able to differentiate the area from the brand. And there was always the possibility that Warren’s neighbors would deliberately ride on his coattails. If there were no brand on a competitor’s label, Stags Leap could appear in large letters as the AVA name, next to the varietal name like Cabernet Sauvignon, and the consumer might think that it was Warren’s or Carl’s wine. Carl pointed to the wines of Châteauneuf-du-Pape as proof positive of what might happen. On those labels, the appellation is typically the most prominent feature, far larger than the brand name. Carl wanted to restrict the appellation name on wine labels to no larger than one quarter the size of the brand name. His proposal was not adopted.

The appellation committee and Warren, but not Carl, soon reached a compromise. Warren agreed to endorse the petition and join the committee if the AVA name was changed to Stags Leap District. The committee held up its end of the bargain by submitting an amended petition to ATF in December 1985. In reflecting back on his decision, Warren later said: I didn’t approve of (the AVA) and wasn’t on board, so to speak, in the efforts to get this viticultural area until there was a clear understanding that we would try to separate proprietary use of the name from the geographic or viticultural use of the name. That came about when the application was modified so that it was for Stags Leap District. The name was not simply the two words, “Stags Leap,” but “Stags Leap District.” I think that was a clear recognition that the effort should be made to apply for a name which would be clearly geographic in character and not proprietary.

The name change was a sensible way to differentiate the brands – Stag’s Leap Wine Cellars and Stags’ Leap Winery – from the winegrowing area. Harkening back to my Old World wine education, the District modifier was akin to adding appellation d’origine contrôlée before or after the name of a French appellation like Margaux, which like Stags Leap is a brand as well as a place. But ATF wouldn’t allow a vintner to add a name modifier when stating the AVA on a wine label.

I found this surprising because of the considerable efforts that ATF had made in the past to avoid consumer confusion over geographic brands, that is, those brands that include geographic references like Stag’s Leap Wine Cellars. ATF, for example, once required that “misdescriptive” geographic brands—that is, those that don’t originate in the place stated in the brand—be modified by ® or ™, symbols that supposedly inform the consumer that the brand is a registered trademark, not a place name. Ultimately, ATF dropped that requirement after concluding that the symbol didn’t clear up the confusion.

When it came to AVA names, ATF wouldn’t accept name modifiers or made-up AVA names. We had to have actual evidence of usage of the proposed name, Stags Leap District. Fortunately, we found just that: Dick’s back label reference to Stags Leap District, that he used when his district dream was still alive. Dick’s label with the exact name of the AVA would be adequate name evidence for ATF. When Warren decided to join the Stags Leap District appellation committee, he put to rest his longstanding quest to control the Stags Leap name. However, he didn’t join the committee without exacting a compromise. The appellation had to be called – and spelled – Stags Leap District. The apostrophe—Stag’s Leap Wine Cellars—indicates possession, and only Warren would possess Stag’s Leap. The appellation committee members accepted this. Other great names like Harrods and Barclays had dropped the apostrophe over time, and so could they.

HOLDING THE LINE

As soon as the change to the AVA name was settled, a boundary fight ensued, and it wasn’t with Warren or Carl. Silverado Vineyards, Walt Disney’s family’s winery, had been included in the AVA, but not its adjacent vineyards to the west and north, which fell outside the summit of the hills and mountains that defined the AVA boundary.

General Manager Jack Stuart, a graduate of Stanford University and the UC Davis Department of Viticulture and Enology, claimed that the soils in Disney’s Silverado Vineyard were more similar to those found in and around Nate Faye’s original vineyard – the heart of Stags Leap District – than to the heavier flatland soils in the southern part of the AVA. The prior owner of the Disney property, Harry See, had followed Nate’s lead and planted Cabernet Sauvignon in this vineyard in 1968/69 which, according to Stuart, helped to establish the reputation of the AVA for distinctive Cabernet Sauvignon wines. In fact, the Disney Silverado clone of Cabernet Sauvignon, also known as the See clone, is one of only three designated Cabernet Sauvignon heritage clones in the state, along with Mondavi To Kalon and Niebaum-Coppola. Stuart also argued that the airflow, fog, elevation, and aspect of the west-facing slopes of Silverado Vineyard were similar to the west-facing, gentle-sloping vineyards below the Stags Leap Palisades. Stuart prepared a counter-petition citing all this evidence, and more, in support of the inclusion of the entire Disney property.

After the Napa Valley and Carneros AVA decisions, I realized, as did Silverado Vineyards, that ATF could not be counted on to hold any boundary firm, especially where the properties on both sides of the boundary line were owned by the same family. Before Silverado Vineyards ever filed its petition, the appellation committee agreed to expand the AVA to include all the Disney property around the winery. To accomplish this, a second amendment to the original petition was filed in June 1986, accompanied by a 60-page research document that Stuart prepared. The revised AVA included approximately 2,550 total acres. The newly expanded petitioning group, including Disney, vowed to fight against any further expansion of the appellation. There was to be no more land accretion.

But the wrangling didn’t end there. Any hope that the new name and boundary for Stags Leap District would be accepted by all was soon dashed. Stan Anderson, who owned the vineyard and winery north of Silverado Vineyards, logically was the next landowner to seek inclusion in the appellation. And he did. Anderson was a former dentist who had moved to Napa in 1971. Like Silverado Vineyards had, he wanted a piece of Stags Leap District, and he saw no bright line other than the appellation committee’s line in the sand to exclude him.

However, unlike the Carneros situation, S. Anderson Vineyard was geographically distinct from the rest of Stags Leap District, outside of its unique orography. Anderson was simply too far north, the committee argued, outside the funnel and outside the main flow of wind and fog. The soils also were different, laid down by the Rector Canyon alluvial fan to the north. Anderson also was an outsider in another sense: S. Anderson Vineyard produced primarily sparkling wines in what was classic Cabernet country.

The committee went to the mat to defend the new boundary, and I was on the front line, overseeing our experts, developing our strategy, and communicating with ATF. We adduced every bit of historical and scientific data that existed or could be developed. The main effort was to show that S. Anderson’s property south of Yountville Cross Road was different than Silverado Vineyards to the south and Sinskey to the east. But there were no climate stations or soil pits in these specific locations, making it impossible to draw such fine distinctions. We pointed out that Stan Anderson and the growers in the excluded area referred to themselves as being in Yountville rather than Stags Leap in the annual Napa Valley Register magazine entitled “Appellation” and that they reported their vineyard locations to Napa Valley Grapegrowers as “Yountville” or the “Yountville Crossroad area.” If the growers themselves advertise their grapes with a different origin—Stags Leap District to the south and Yountville to the north—surely ATF would draw the line where the petitioners proposed.

We also uncovered historical name evidence supporting the proposed boundary, namely, the 1893 report of the State of California Board of Viticultural Commissioners that listed the northern extension properties as being in the “Yountville District.” We even suggested that ATF taste the wines made from grapes grown in these two areas and compare the harvest dates and other viticultural and enological characteristics.

At this juncture, I considered adopting the method of defining an appellation that I had observed in France, developed by the Bureau de recherche géologique et minière. In France, when someone seeks to amend—usually expand—an appellation, the new area under consideration is compared, in terms of all its physical features, to a specific area inside the vineyard that everyone agrees is the archetypical terroir of that same appellation. The degree of deviation from that benchmark determines in large measure whether the new area is admitted into the appellation or not.

Unfortunately, there was no way to conduct such an objective comparison in Stags Leap District. We simply didn’t have sufficient data to do that. And, in any case, ATF—and many vintners—likely wouldn’t agree on what comprises the archetypical Stags Leap District terroir.

ATF’s reaction to the evidence that we presented in the battle over Stags Leap District, as reflected in its Final Rule, illustrates clearly the arguments that resonate with ATF and those that do not. ATF doesn’t place much faith in harvest dates or taste features, reasoning that there are too many subjective factors that can influence these criteria. Likewise, it doesn’t care what grape varieties Stan Anderson or any other grower planted, and it doesn’t take into account grape prices. It doesn’t care if the grapegrowers north of the hills referred to their own location as Yountville because, in ATF’s own words, “there was no contradiction between using a Yountville address and being within the Stags Leap District viticultural area.” Finally, when it comes to boundaries, although the petitioners relied on natural features—mountain peaks and elevation contour lines—ATF opted for man-made structures like roads. While the vintners and growers were searching for on-the-ground boundaries that capture terroir and that offer consumers, in Warren’ words, “a geographical basis for wines of familial resemblance,” ATF was concerned about administering the appellation program and determining without complication what vines are in, and what vines are out, of the AVA.

In the end, ATF did put its foot down and rejected several last-minute requests for inclusion in the appellation. At the public hearing that ATF held in Napa in December of 1987, George Altamura proposed that the southern boundary of the AVA be extended about two miles south to include Altamura Vineyards and Winery which, he contended, shared “many of the same geographical features…including soils series, vegetation, and air-flow pattern.” Then Ernie Weir, whose Hagafen Cellars is located one-eighth of a mile south of Altamura, said that if Altamura were included in the AVA, so should he be, though he added that “perhaps a more appropriate and correct southern border will not include either of us.” Neither Altamura nor Weir offered any evidence that their properties were ever known as Stags Leap or Stags Leap District.

In the Final Rule, published in January 1989, ATF admitted S. Anderson because it found that there was insufficient evidence to distinguish the climate and soil north and south of the ring of hills from one another. With respect to the all-important Bale clay loam soils, the agency found the transitional soils in the disputed area to be more akin to the soils of the rest of the AVA than to those north of the Yountville Cross Road.

The saga of Stags Leap reveals the power of a name. It was the first time that a name already made prominent by a winery (or in this case, two wineries) was “taken” by a larger vintner-grower group as the name of an appellation. It would not be the last. Just as important, the saga reveals the winemakers’ and grapegrowers’ fear of being excluded. Wine appellations, or at least the best of them, offer producers a collective value added, in the form of a price premium, because consumers regard these wines as “a cut above” the norm, with special character and quality. Whether or not this is true of any particular wine, the appellation serves as a magnet. To be left out, particularly just on the other side of a boundary, would be humiliating and infuriating. The fight is not only about money—a higher grape price, a higher bottle price, and higher land values inside the appellation—but also about human nature, prestige, and the fear and ignominy of being excluded. In light of these basic needs and pressures, appellation decisions must be principled and objective.

Aside from the name, the Stags Leap District affair demonstrated how difficult it is to draw appellation boundaries on the floor of the Napa Valley. The distinguishing physical features are subtle, and the boundaries that capture those subtleties are hard to locate and define. Taste is one way to make these decisions—a possible reference point to guide the decision-makers, as occurs in France. But taste, by its very nature, is subjective, and ATF was disinclined to undertake, and in any event ill equipped for, the task.

Credits:

Stag illustration: Emily Bonnes

Stags Leap AVA original proposal in 1985 (left), Stags Leap AVA as finalized in January 1989 (right): Sarah Lewis MacDonald

For a limited time Vinous subscribers can take advantage an exclusive offer of 40% off both the First Edition and Limited Edition (500 copies printed) of Appellation Napa Valley – Building and Protecting an American Treasure by using the coupon VINOUS17, at checkout, when purchasing the book through the publisher’s website (appellationnapavalley.com).

Offer expires August 15, 2017.

Orders will be fulfilled directly from the publisher. Please direct any questions about your order or Appellation Napa Valley – Building and Protecting an American Treasure to info@appellationnapavalley.com.

You Might Also Enjoy

The Rutherford and Oakville AVAs - Early Days, Richard Mendelson, September 2016

A Brief History of Napa Valley, Part II: SURVIVING PROHIBITION & THE RECOVERY YEARS, 1920–1959, Kelli White, June 2016

Book Excerpt: A Brief History of Napa Valley, Part 1, Kelli White, April 2016