Browse using the new Vinous website now. Launch →

Printed by, and for the sole use of . All rights reserved © 2015 Vinous Media

Exploring Sonoma’s Moon Mountain District

BY ANTONIO GALLONI | FEBRUARY 12, 2025

Nestled in the Mayacamas Mountains just east of the town of Sonoma, the Moon Mountain District is one of the most exciting emerging appellations in California. These hillside vineyards offer an intriguing mix of the old and the new, a melting pot of historic vineyards, established players and a generation of younger winemakers who are bringing their energy and enthusiasm to these sites.

I have long been fascinated by the wines from this stretch of land. The first Moon Mountain wine I remember tasting was a Cabernet Sauvignon from Ed Sbragia about 15 years ago. It was so distinctive and so incredibly different from the Napa Valley Cabernets I tasted on that trip. Sbragia spoke about a vineyard called Monte Rosso that was on the other side of Mt. Veeder. I had a vague notion of where that was but not a clear idea. That was my first real introduction to Sonoma Cabernet Sauvignon. I was immediately hooked.

Later, I had the opportunity to taste many Martini wines from the 1950s and 1960s that told the story of a remarkable place. First planted in 1882, Monte Rosso is one of the most iconic vineyards in the United States. Nearby Moon Mountain Vineyard, established around the same time, is another example of the rich legacy that lies within these rugged hills. Eventually that interest led to a map of the AVA that we created with Alessandro Masnaghetti as part of a full set of Sonoma Valley maps we published in 2021. Portions of this text are taken from that map.

Covering Moon Mountain presents some logistical challenges. This article covers estates that are physically in Moon Mountain. Many other estates in Napa and Sonoma source fruit from sites in the appellation. Additionally, many producers use the broader Sonoma Valley and/or Sonoma County AVAs for wines made from Moon Mountain fruit. This makes it difficult for consumers, sommeliers and the wine trade to understand the true breadth of Moon Mountain wines and could also be perceived by the market as a lack of confidence in the AVA. Examples include some pretty big names, such as Bedrock, Kistler, Turley and, most surprisingly of all, Louis M. Martini, part of the Gallo family’s holdings that also include Monte Rosso.

That’s a shame, because the whole idea of site-driven wines is specificity. Sonoma Valley is a vast AVA that also includes Bennett Valley, Sonoma Mountain, the Central Corridor and a part of Carneros, none of which have anything in common with Moon Mountain, with the sole exception of sites along Highway 12 that form the Central Corridor. The parallel would be making a wine from Vosne-Romanée fruit and opting to label that wine Côte de Nuits or even Côte-d’Or. In my view, this is a missed opportunity to elevate the visibility of one of California’s great terroirs.

Head-trained Zinfandel at Monte Rosso planted in the

1880s.

Moon Mountain District AVA – An Overview

Established in 2013, the Moon Mountain District is one of the more recent California AVAs, even though a few estates boast track records that go back much further than that. The Moon Mountain District essentially lies on the western side of the Mayacamas Mountains, bordering the Mt. Veeder AVA on the adjacent, eastern side of the Mayacamas Mountains in Napa Valley. The Moon Mountain District AVA covers 17,663 total acres and more than 1,500 acres of vineyards, many of them scattered across an expanse of land that is quite vast considering the relatively small amount of vineyard acreage. Starting with vineyards at 400 feet in elevation moving east from Sonoma Highway on the valley floor, the AVA reaches approximately 2,600 feet at the ridgeline separating Sonoma and Napa counties, along the border with Mt. Veeder.

The differences between Moon Mountain and Mt. Veeder are fascinating to contemplate, as the two regions occupy opposite faces of the same mountain range. The Moon Mountain side is warmer and more exposed, while Mt. Veeder sees more rain and is characterized by distinctly verdant landscapes and steeper hillsides. Crossing into Moon Mountain from neighboring Mt. Veeder, the change from lush greens to more rugged, chaparral-based vegetation is immediately evident.

In some places, especially in its center tenderloin of vineyards (Monte Rosso, Wildwood), Moon Mountain is reminiscent of the eastern hills of Oakville in its altitude, soils and generally western exposure—specifically the stretch of land that encompasses Dalla Valle, Peter Michael and Oakville Ranch. But Moon Mountain is one large ridge further west and is therefore cooler because of its greater proximity to the Pacific Ocean. In its upper elevations, Moon Mountain resembles Howell Mountain and parts of Pritchard Hill, where vineyards also reach 2,000-foot elevations. These sites, like those on Howell Mountain and Pritchard Hill, are deeply influenced by the fog inversion layer at 1,200 to 1,500 feet. The inversion later, or thermal gradient in more technical terms, is created by cooling late afternoon and evening temperatures that cause colder air to drop down into the valley, turning water vapor at lower elevations into fog through condensation. Above the inversion layer, temperatures are higher, and therefore above the dew point that creates valley fog. The following day, warming temperatures cause fog to turn to vapor and dissipate. This creates several interesting phenomena in sites above the inversion layer, including condensed growing seasons marked by late budbreak, warm nights and diurnal shifts that are relatively compact. In other words, temperatures at higher elevations above the fog line are often warmer than they are on the valley floor below where the fog settles.

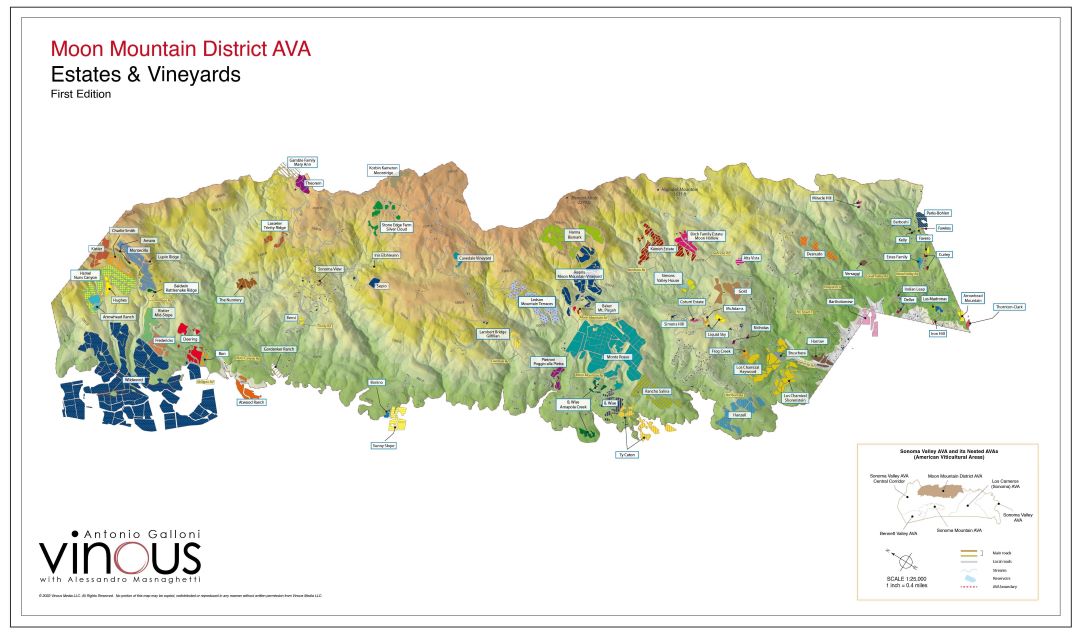

The Vinous Map of the Vineyards of the Moon Mountain

District AVA by Antonio Galloni and Alessandro Masnaghetti. This map is part of

a six-map Sonoma Valley set that includes Bennett Valley, Sonoma Mountain, Los

Carneros (Sonoma) and the Central Corridor. © Vinous, 2025.

A Brief History

Much of this terrain dates to the original land grants given by Mexico to California’s early settlers. The first privately owned vineyard was planted in 1832 at what today is Bartholomew. Hungarian Count Agoston Haraszthy purchased this land in 1857 and built Buena Vista Winery, widely considered to be California’s first premium winery. In 1879, John Drummond planted his first vines using cuttings from France in vineyards that would later become part of Wildwood. The ruins of Drummond’s original Dunfillan Winery are still standing and remain a poignant reminder of California’s early days. Emmanuel Goldstein and Benjamin Dreyfus planted their Mount Pisgah (later Monte Rosso) estate in 1882.

A period of significant challenges followed. Phylloxera took a considerable toll on many vineyards in the late 1880s and 1890s. Prohibition, which was in effect from 1920 to 1933, caused most estates to cease production entirely, but a few were able to survive by farming grapes for sacramental wines. There was not much activity during World War II, for obvious reasons. It was not until the late 1960s and 1970s that interest in farming grapes for wine began to pick up.

The term “Moon Mountain” in reference to a specific place was only formally adopted in 2007, but cultural references to the name go back to at least the early 1900s. Jack London’s 1913 novel, “Valley of the Moon,” a literal translation of the word Sonoma, is taken from the language spoken by Indigenous Pomo, Wappo and Miwok tribes. London was one of the most influential American authors of the late 1890s and early 1900s and an important figure in the early history of Sonoma, as we will explore in several maps within this collection. Moon Mountain Road (previously Goldstein Road), which runs through Monte Rosso, was once an important thoroughfare at a time when options for travel were quite limited. More recently, fire events in 1996 and 2017 have changed some of the natural landscape.

Geology & Soils

Moon Mountain is a collection of distinct microclimates that are heavily influenced by a combination of soils, altitude, exposure to sun, and winds coming in from the San Pablo Bay. As mentioned above, the western exposures, terrain and vegetation are at times quite similar to those found on the eastern side of Napa Valley in places such as Oakville, except that the Sonoma side is naturally more heavily influenced by its closer proximity to the ocean and the cooling effect of wind coming off the water.

Subsoils are Sonoma volcanic, a formation that was created approximately 2.5 to 5 million years ago during the Pliocene era when the Pacific Plate picked up the North American plate, generating a series of eruptions and landslides over many centuries. The resulting mosaic of topsoils is quite complex and is predominantly composed of red, iron-rich soils, whiter ash deposits of alluvial origins, and a range of loamier terrains. Soils are heavier on the lower slopes, because of erosion over long periods of time, and are more varied moving into the higher elevations.

No discussion of Moon Mountain soils and vineyards is complete without a mention of the profound impact viticulturalist Phil Coturri has had on the region. Coturri was an early champion of biodynamic and sustainable farming practices decades before they gained mainstream approval. His work in many of the region’s top sites has profoundly influenced the methods with which soils are worked, and consequently, the potential results for the wines that are made here.

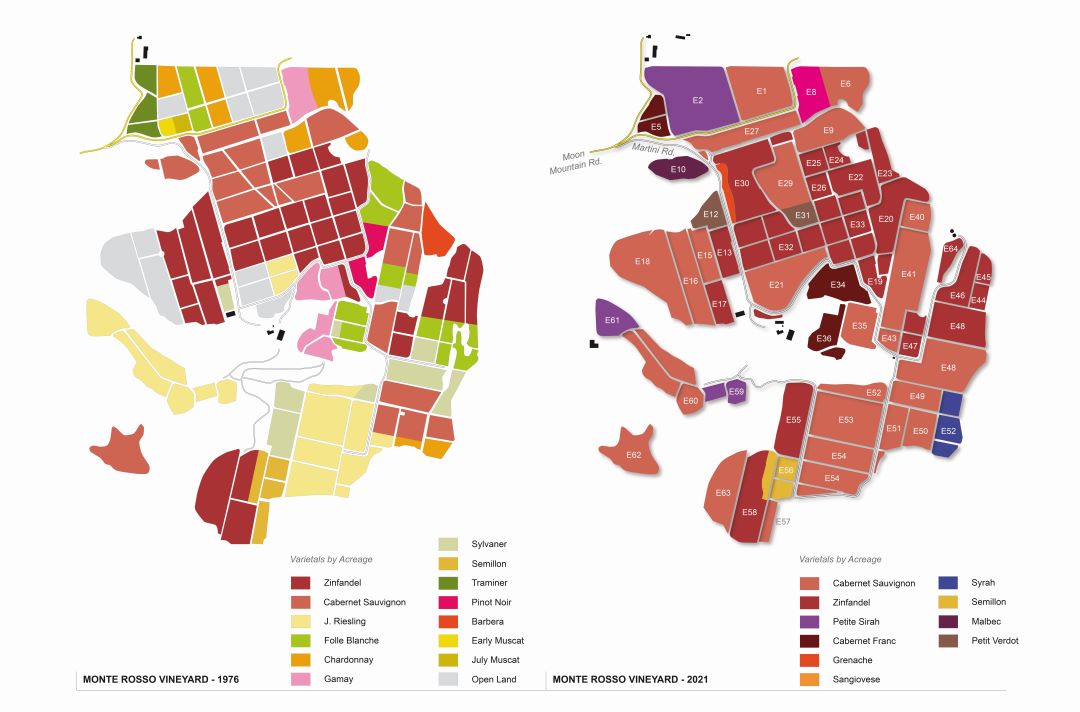

Surveying the Viticultural Landscape

Like many parts of California, the viticultural landscape here was once quite varied. Bordeaux red varieties comprise most of the planted acreage today, although in earlier times white grapes played a more prominent role, as can be seen in the 1976/2021 comparison of Monte Rosso shown below. Among red grapes, Cabernet Sauvignon and Zinfandel represent the lion’s share of plantings. One of the more recent developments is a greater focus on Cabernet Franc, which is yielding interesting results. Pinot Noir is less commonly found, Hanzell being a notable exception, while Rhône varieties play a minor but increasingly interesting role.

Moon Mountain Chardonnays have long been distinctive. Kistler, Mid-Slope (formerly Chuy) and Hanzell are among the sites with a long track record of producing incredibly unique Chardonnays. Sauvignon Blanc and Sémillon can also be quite interesting. Sadly, there is not much left in the way of old-vine white grapes, except for one or two historic plantings.

This comparison of varietal breakdown at Monte Rosso from

1976 and 2021 shows a move over time towards Cabernet

Sauvignon and Zinfandel and the near extinction of white grapes. Excerpt taken from The Vinous Map of the Vineyards of the Moon Mountain District AVA by Antonio Galloni and Alessandro Masnaghetti. © Vinous, 2025.

Wines & Vintages

Moon Mountain wines run the gamut stylistically. Those made by younger producers tend to emphasize greater focus and energy than those made by older estates. That’s not too dissimilar from Napa Valley, but here concentration and heavy extraction are the norm at quite a few wineries, especially those based within the appellation. Some estates, not necessarily covered in this report, make potent, super-opulent wines. Perhaps producers feel they need to make a statement, that they need to make showy wines. But they don’t. The land speaks for itself, when allowed. I think there is a real opportunity for the wines to be a bit more contemporary and more closely aligned with a region whose history goes back to the 1800s. I would not say that of newer viticultural regions like Paso Robles or the Santa Lucia Highlands, where there are no multi-generational historical precedents. But in Moon Mountain, a more site-driven style would almost certainly bring these estates and wines greater prominence, especially on the global stage.

Recent vintages in Moon Mountain largely track those in nearby Napa Valley. The 2023 whites are bright and nervy, very much in the style of this cool, late-ripening year. Two thousand twenty-two was especially challenging here. Sugars soared to unprecedented levels, which required considerable adjustments in the cellar. Even so, many wines show the strong imprint of a growing season marked by intense heat and drought. The degree to which this is accentuated by some producers’ preference to pick late is hard to say with precision. What is obvious is that the 2022 reds are very ripe, with angular contours that are a telltale sign of stress in ripening. Some wines were not bottled at all. Two thousand twenty-one, on the other hand, is very strong across the board.

Other Notable Moon Mountain Wines

Bedrock – Cabernet Sauvignon Montecillo, Zinfandel Monte Rosso

Beta – Cabernet Sauvignon Montecillo Vineyard

Di Costanzo – Sauvignon Montecillo Vineyard

Kistler – Chardonnay Kistler Vineyard, Chardonnay Kistler Vineyard Cuvée Cathleen

Louis M. Martini – Cabernet Sauvignon Monte Rosso Vineyard, Gnarly Vine Zinfandel Monte Rosso Vineyard

Limerick Lane – Zinfandel Monte Rosso Vineyard

Newfound – Mourvèdre, Grenache, Syrah Maus Vineyard

Reeve – Sangiovese Monte Rosso Vineyard

Turley – Cabernet Sauvignon Montecillo Vineyard, Zinfandel Fredericks Vineyard,

Zinfandel Monte Rosso Vineyard

You Might Also Enjoy

Sonoma and Neighbors 2022 & 2023: Opposites Attract, Antonio Galloni, January 2025

2022 Sonoma: A First Look, Antonio Galloni, January 2024

Sonoma’s Sensational 2021s, Antonio Galloni, August 2023

California North Coast: Eyes Wide Open, Antonio Galloni, January 2022

Sonoma: 2021 New Releases, Antonio Galloni, January 2021

Show all the wines (sorted by score)

- B. Wise Vineyards

- Charlie LaRue

- Charlie LaRue Wines

- Far Mountain

- Gail Wines

- Hanzell Farm

- Hanzell Vineyards

- Hill of Tara Winery

- Kamen

- Korbin Kameron

- Lasseter Family Winery

- Liquid Sky Vineyards

- Monte Rosso Estate

- Moon Hollow

- Mountain Terraces Winery & Vineyard

- Muscardini Cellars

- Repris

- Robert Biale Vineyards

- Sojourn Cellars

- Stone Edge Farm Estate Vineyards & Winery

- Winery Sixteen 600