Browse using the new Vinous website now. Launch →

Printed by, and for the sole use of . All rights reserved © 2015 Vinous Media

Grower Spotlight: Dick Steltzner

BY KELLI WHITE | JANUARY 11, 2017

It was January 7, 1976 and only eight days remained in duck season. Dick Steltzner and a friend had spent the better part of the day hunting in Chiles Valley, but had little to show for their efforts. They loaded their meager haul into Steltzner’s single engine plane and pointed back towards Napa, but Steltzner remained unsatisfied. Somewhere close to the east-facing slopes of the Vaca mountains, he decided to buzz some irrigation ponds, flying lower and slower than is recommended, in the hopes of spotting some ducks. Instead, he unbalanced his typically nimble little “flying jeep”, as he calls it, and smashed into the hillside, ending ‘wheels up’ in the worst way imaginable.

With his seriously broken legs framing the sky above him, Steltzner might have hardly considered that he had found himself, once again, in the right place at the right time. And yet, several thousand feet overhead, a skydiving plane was preparing to unload its passengers, an orthopedic surgeon among them. The pilot radioed in the crash’s location while the doctor jumped down to assist. It took the fire department six hours to cut a path through the thick mountain scrub, while the doctor worked to stabilize the two men’s injuries. If the crash had not been spotted immediately and a doctor not been on-hand, Steltzner’s probability of survival was almost certainly zero.

Steltzner spent the following 52 days in the hospital and, despite the severity of his injuries, his spirits remained high. Friends came and went constantly and almost always brought wine, which they gladly shared with patients and hospital staffers alike. Once he gained in strength, Steltzner would race around the hallways in a wheelchair. By the time he left, empty bottles lined all the sills of his room and Steltzner had formed the basis of a surgeon-studded mailing list for the wine brand he would launch the following year. The nurses said they’d miss him, and more than one confessed that they could practically find their way to his room with their eyes closed, drawn towards it by the smell of wine and the sound of constant laughter.

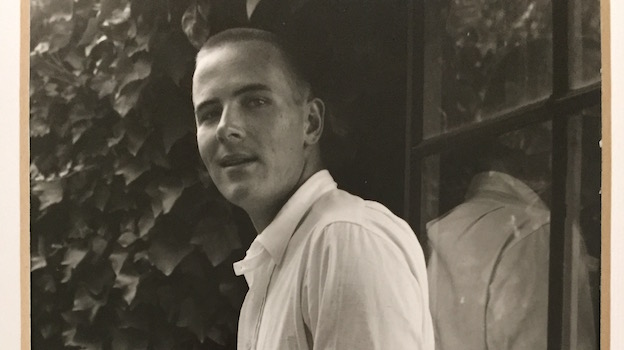

A young Dick Steltzner, shortly after his arrival in Napa Valley

Dick Steltzner was born and raised in Piedmont, California – just outside of Oakland. His mother was a member of the extended Schilling family of Schilling spices (now McCormick). Although this particular branch of the family had effectively run through their fortune by the time Steltzner came along, the name still carried weight within San Francisco society, and they retained a handful of aristocratic tendencies, such as regular travel to Europe and the drinking of wine with dinner. The Wente family of Livermore moved in similar social circles, and young Dick Steltzner spent much of his childhood playing on their ranch. Those bucolic summers instilled in him a love of farming and gave him a familiarity with viticulture, which would prove handy in the years to come.

After graduating college with a degree in the ceramic arts, Steltzner sought a quiet, inexpensive place to live where he could focus on his pottery. As he had family in Napa Valley (his uncle briefly owned La Perla on Spring Mountain, now a part of Spring Mountain Vineyards), he moved to Calistoga in 1960. Soon, however, he found himself drawn to the wine industry. A self-described Riesling fanatic, Dick worshipped Stony Hill, and convinced Fred McCrea to allow him to scour the vineyards after a harvest and keep any crop left on the vine. He scavenged enough fruit for one barrel, which he fermented in the caves at Schramsberg. When the resulting wine earned a nod from his father, Steltzner’s commitment to the wine industry was cemented.

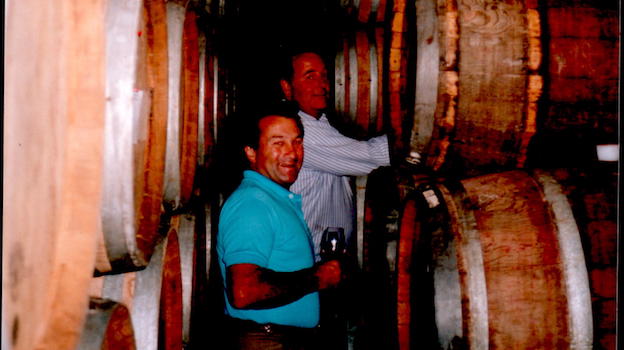

Steltzner (right) in the cellar, circa 1980

Shortly thereafter, Steltzner bought 40 acres on Diamond Mountain for $2,000. The property touched on both of his passions, boasting a World War II-era clay mine as well as a similar elevation and aspect to Stony Hill. Dick eagerly sketched out his dream Riesling vineyard, and began developing the property. The road that he built traced the edges of what would become Diamond Creek, and its owners, the Brounsteins, quickly befriended the would-be potter.

A turning point in Steltzner’s trajectory came when the initial plantings at Diamond Creek all mysteriously died. Steltzner stepped in to assist, drawing upon his childhood experience with vineyards, and was able to successfully redevelop the property, becoming the storied estate’s first vineyard manager in the process. This experience lit a spark in Steltzner, who examined the wave of investment in Napa in the 1960s with an entrepreneurial eye. Many of these aspiring new vintners were coming to Napa from outside the agricultural sphere, and were in desperate need of guidance. In addition, a good portion were small to medium in size, and the dominant farming companies of the day preferred to work mostly with larger scale operations. Steltzner’s artisan viticultural services fulfilled a real need at this fertile time in the valley’s history, and he would eventually grow to manage dozens of clients and over 400 acres of vines across Napa.

Dick Steltzner prepping his Stags Leap vineyard for redevelopment, circa 1991

In 1964, shortly after he had purchased his Diamond Mountain parcel, Steltzner was offered a handsome sum for the as-yet undeveloped land, which he gladly accepted. He took this money and moved his operation to the Stags Leap District, which at this point in time was relatively unpopulated. Over the ensuing decades, Steltzner would play a critical role in the development of the region. The fruit from his vineyard informed such legendary wines as the 1972 Clos du Val Cabernet Sauvignon that placed fourth in the Judgment of Paris (Clos du Val bought Steltzner fruit while waiting for their own vineyard to mature) and the inaugural 1974 Joseph Phelps Insignia. Heitz Cellars also vineyard designated a Steltzner Cabernet at some point during the 1970s. Beyond the confines of his own vineyard, Steltzner also developed and managed the vines at Clos du Val, assisted Joseph Phelps in securing his Stags Leap vineyard, and was instrumental in the formation of the Stags Leap District AVA. Steltzner’s own brand, which debuted in 1977, also did much to elevate the reputation of the region, although the quality faltered a bit in the 90s and early 2000s, when they built a winery and expanded their production. Burdened by the hospitality requirements of their size, the Steltzner family sold their winery and front half of their vineyard to the PlumpJack group in 2012, who founded Odette on the site. Newly streamlined, the Steltzner brand, which is now partly run by Steltzner's daughter Allison, has undergone something of a rebirth. Allison and her husband Sam Sharp have also launched Bench Vineyards, whose Red Wine and ‘Circa 64’ Cabernet are crafted from Steltzner fruit.

A close up of Vinous Napa Valley Vineyard Maps, Stags Leap

But as significant as his work in the Stags Leap District might be, it can be argued that Dick Steltzner’s most important contributions to the development of Napa Valley were his efforts surrounding rootstock and clonal diversity. When Steltzner first took up residence in Stags Leap, he purchased the land next to Nathan Fay and became only the second grower to plant Cabernet Sauvignon in the area. His heart, however, still belonged to Riesling. Gifted with a naturally curious intellect, Steltzner sought to learn more about his favorite variety, and sent himself to Geisenheim in 1968. There he met a man named Dr. Becker who took Steltzner under his wing. In addition to introducing him to a wide selection of Rieslings, Dr. Becker issued Steltzner a grave and prophetic warning: that AxR-1, the rootstock being promoted by UC Davis as a more productive substitute for stubborn old St. George, was widely known in Europe to be susceptible to phylloxera.

Steltzner pruning, circa 1996

Steltzner returned wary of the popular rootstock but didn’t begin actively campaigning against it until the mid-1970s when a Chilean man named Gallo McClean moved to the valley. Gallo was a vineyard developer with seven viticulture/enology degrees and a broad international experience; he had personally seen vineyards planted on AxR-1 succumb to phylloxera. His story galvanized Steltzner, as the trickle of development in the 1960s had become a flood by the mid-70s, and the majority of new vineyards were being planted on these faulty roots. In addition to alienating him from the establishment, Steltzner’s vocal anti-AxR-1 stance cost him a good amount of business. At this point in Napa’s history, a property owner wishing to develop a vineyard would likely call the Farm Advisor, who would inspect the site and make a series of recommendations that covered where to plant, what to plant, and which clones and rootstocks to utilize. A vineyard manager was then hired to execute the Farm Advisor’s vision. Steltzner’s constant clashing with the Farm Advisor’s suggestions confused and alarmed many proprietors, who often simply looked for a new vineyard manager rather than go up against such a respected authority.

Steltzner’s proselytizing, however, did occasionally land on welcome ears, and those who listened often benefitted greatly. Philip Togni was among the early Steltzner believers. “I first met Dick Steltzner in the early 1960s when we were both taking a class at UC Davis,” Togni recalls. “I remember being impressed by him when, in the middle of the class, he pulled out some studies and statistics from the Wall Street Journal. I thought here was an [intellectually] wider guy than I was used to seeing.” Togni saw Steltzner only rarely in the years that followed, until the mid-1980s when Steltzner was managing the vineyards at Keenan, which surrounds Togni’s property on three sides. Philip and his wife Birgitta had already planted half their vineyard on AxR-1, but a conversation over the fence with Steltzner convinced them to change their strategy, which ultimately saved them both the cost of a replant and the time and income that is lost while waiting for new vines to mature. Togni remains grateful for the advice, adding, “any time you meet Dick Steltzner you learn something of value.”

Steltzner Vineyard, Stags Leap District

As Steltzner’s business grew, so did his frustration with the tools available to viticulturalists, and his ire quickly moved upward from the rootstock to the scion. He blamed UC Davis in particular for the lack of clonal diversity in Napa’s vineyards, explaining, “I was part of a growing movement that thought Davis was moving in the wrong direction. There, the emphasis was purely on cleanliness, mostly lack of virus, over all other qualities including taste.” As early as 1979, Steltzner began exploiting loopholes in international and interstate agricultural shipping laws to sneak in his own plant material. California was especially strict; most roads leading into and out of the state still have agricultural checkpoints, and shipping anything directly resulted in a lengthy and often qualitatively compromising period of quarantine. Steltzner preferred not to wait and so had new vinifera clones, already grafted onto resistant rootstocks such as the then-uncommon SO4 and 110R, shipped to Canada. He would then go on his annual ski trip to Idaho, dart over the border to collect his contraband, and drive it nonchalantly into California in the bed of his pickup truck, concealed beneath layers of snow and ski equipment.

This gleeful lawlessness continued for several years, and in the mid-1980s Steltzner upped his game. He had begun travelling regularly to Europe, spending time at both the University of Montpellier and the famed Italian nursery, Rauscedo. Though by this time Napa Valley was becoming increasingly cosmopolitan, it was still a rare thing for a vineyard manager to spend so much time abroad. Steltzner struck up a close relationship with both institutions, and even got on the harvest rotation for Montpellier students, whom he enlisted in his mischief. Once his interns returned home after their harvest in Stags Leap, Steltzner had Rauscedo send them budwood that he had selected (mostly Merlot and some Sangiovese). The students would then wrap the sticks in plastic, hide them inside a board game or similarly benign vessel, wrap the package with holiday paper and ship it to Steltzner in the guise of a Christmas present.

Steltzner's self-imported Sangiovese clone

Though such an elaborate ploy may seem over-the-top today, Steltzner was doing what he thought necessary to improve not only his own product, but to enhance viticulture in Napa Valley at large. And he was not alone in his actions; John Caldwell also famously smuggled vines into California, and many producers admit with a wink to ‘importing’ their own cuttings in the bottom of their suitcases following trips to Bordeaux or Burgundy, though few are as willing to go on record with their antics. And while the vineyard managers of today have a wealth of government-sanctioned options to select from, many of California’s most beloved clones, many of them labeled as ‘heritage’, came in via these illicit channels.

In short, Napa Valley owes Dick Steltzner an enormous debt of gratitude. Though it could be argued that luck played as much a part in aligning Steltzner’s personal crossroads with the valley’s post-Prohibition awakening as it did in positioning an adrenalin-seeking surgeon above the site of his plane crash, that is but the smallest part of the story. It was a combination of savvy and fearlessness that enabled Steltzner, with no formal training, to carve himself a leading role in Napa’s rebirth of the 60s, 70s, and 80s. It was his tenacious intellect that sent him again and again to Europe’s leading viticultural centers in an endless effort to improve his craft. It was his distaste for bureaucracy and stubborn will that enabled him to rail against AxR-1, even when it affected his reputation and livelihood. And it was his rebellious side in hand with his commitment to quality that inspired him to skirt the law, when following that law meant settling for less. Although it seems to be the lot of those who prefer the field to the cellar to be overshadowed by winemakers and proprietors, their contribution to the greatness of wines and wine regions is just as essential. This is especially true of Dick Steltzner who, at more than one critical juncture in Napa’s history, broadened the valley with his breadth.

Allison and Dick Steltzner, celebrating a vintage release

You Might Also Enjoy

Multimedia: A Conversation with Dick Steltzner, Kelli White, January 2017

Vinous Napa Valley Vineyard Maps

Meet the Mahers: Two Premier Grape Growers in One Household, Kelli White, June 2016

Old Vines, Deep Roots: Calistoga's Frediani Family, Kelli White, March 2016

Dry Times in Napa Valley, Kelli White, September 2015