Browse using the new Vinous website now. Launch →

Printed by, and for the sole use of . All rights reserved © 2015 Vinous Media

Cellar Journal – Bordeaux to Start…

BY NEAL MARTIN | JULY 19, 2018

The Japanese have a custom called “fukubukuro”. It literally translates as “lucky grab bags”. Every New Year, department stores sell these bags giving no indication what they might contain. Such is the popularity of fukubukuro that people queue for hours in order to purchase a bag, take it home and see what is inside. In a sense, we see “Cellar Journal” as a vinous “fukubukuro”. Think of it as your lucky bag. Of course, there will be a theme, more often than not, Bordeaux or Burgundy, but the exact bottles contained within each article will be a surprise. These articles comprise miscellaneous bottles that do not merit standalone pieces, lest I bore readers with an article every hour. Almost every day I encounter fascinating wines, many of which serve to update old reviews and fill in gaps in the database, not least esoteric producers and forgotten vintages. They are all part of the tapestry of our vinous experiences and coverage of a region should embrace not just its historical highs but also the lows. Off vintages often have as much to offer as fêted seasons, often a truer test of a property’s performance than one where everything was easy.

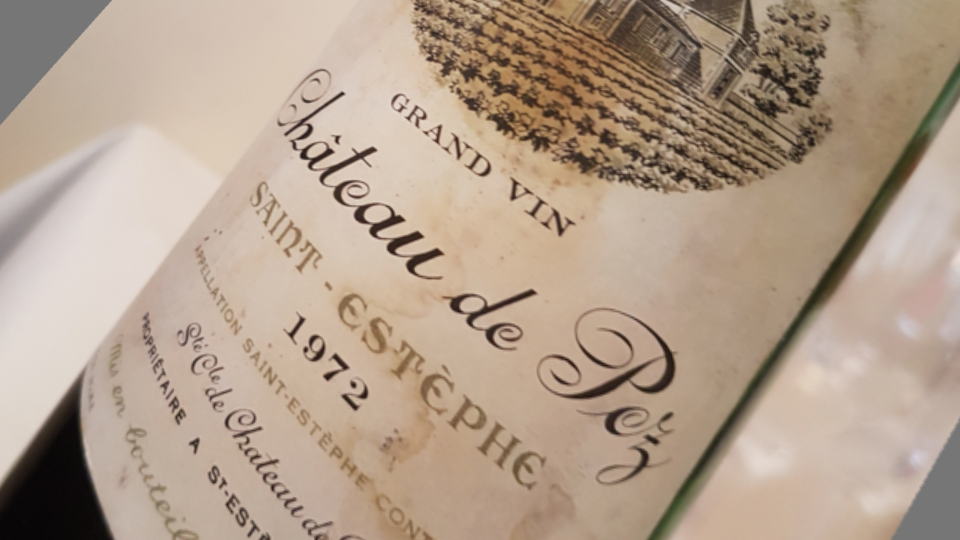

A good example here is the 1972 Château de Pez. It is a lesser-known Saint-Estèphe from a derided decade born in an appalling growing season. The chances of readers encountering the same wine are small, therefore, why record it now? Two reasons. Firstly, it is because nothing can be gained not recording my opinion for posterity. Secondly, because the wine was served blind and defied not just my own, but every participants’ expectations. That is something that should be shared with readers, whether these stragglers are mighty legends or complete unknowns. At the end of the day, this pick ‘n mix may include a bottle gathering dust in your cellar or about to appear at auction.

Venturing to vintages others dare not go

Before broaching the wines, readers should note that many of these bottles were tasted and reviewed blind, even some of the most expensive ones. This will always be mentioned in the note, just in case you might erroneously assume label or age swayed judgment. Also, I always note where the bottle was encountered because as time passes, the same wines crop up repeatedly and it is vital to differentiate one from another and account for any changes. Some might be tasted at the property and others, like the so-called “Philip’s Belated Christmas Lunch”, are more informal but just as informative (this particular blind tasting boasting a number of esoteric wines that I had not seen for a long time.) By noting the time and place of the review, if queries subsequently arise, then I can always explain how it might have been served, the provenance and so on.

This first “Cellar Journal” focuses on Bordeaux and depending upon what comes my way, I will try to alternate it with Burgundy down the line. I will not give context to all the wines, however I will pick out mini-verticals or bottles that do deserve attention. For example, you will find here five vintages of Haut Brion Blanc from 1964 to 2009. It comes from 3 hectares of vines more or less equally divided between Sémillon and Sauvignon Blanc. Though Haut-Brion Blanc is always offered for sale during en primeur, historically it was the Woltners’ private cuvée, ergo very few bottles ended up on the market. There is also another showing of the 1986 Bâtard Chevalier, the erstwhile mischievously titled deuxième vin of Domaine de Chevalier. Even though it was a well-meaning homage, apparently Vincent Leflaive was “not amused” and the name withdrawn by Olivier Bernard. This third bottle from a batch I bought last year was actually the best and even after 30 years remains fresh and vital despite the titular confusion about which region it belongs to.

Moving onto the gallimaufry of reds, the oldest included here is the 1945 Pontet Canet. I have rarely been impressed by venerable vintages of this Pauillac, when practically all the production was bottled by merchants and unlike today, quantity was prioritized over quality. Not until Alfred Tesseron began steering the estate in a pioneering and prescient direction in the 1990s did Pontet Canet begin producing wine worth talking about. This 1945 was fresh, but pause and consider what Baron Philippe created next door at Mouton-Rothschild that year. There are wines here that probably deserve an article of their own by dint rarity. You don’t encounter the 1959 Latour-à-Pomerol too often or 1952 Magdelaine. Ah...Magdelaine. Like Laville Haut-Brion, it has a fan club of oenophiles who still bristle that it ceased to exist after being absorbed into Bélair-Monange, after the Moueix family’s acquisition. Magdelaine’s final outing came courtesy of the 2011 vintage and yet its cult following has grown, not least because of a posthumous appreciation of this classically styled and age-worthy Saint-Émilion. Both the 1952 and a 1971 Magdelaine did nothing to dispel the idea that this was a great Saint-Émilion, always had a propensity to age better than most of its self-aggrandizing peers.

The apotheosis of fermented grape juice nestling amongst this tranche is undoubtedly the 1961 La Mission Haut Brion opened for a spectacular lunch at Howard’s Gourmet restaurant in Hong Kong. Alongside the 1961 Latour and 1961 Palmer, it ranks as one of the best examples of this epochal vintage. As I mention in my note, the only reason I refrain from a perfect score is because I have been privileged with an imperious 1955. That takes nothing away from this monumental and majestic wine that purrs like a Bentley. More up to date and possibly within the realms of affordability, I was also deeply impressed by a 2005 Pensées de Lafleur. Winemaker and proprietor Baptiste Guinaudeau handed me a bottle and asked my opinion of one of the very few vintages I had never tasted. Though not technically a second wine since it comes from a specific parcel of their sandier soils, I was still startled by its precision, intensity and complexity. It will easily give 25, possibly 30, years of drinking pleasure. (As an aside, readers should expect a Lafleur and Pensées de Lafleur retrospective in the future). Staying with Pomerol, I squeeze in a mini-vertical of Nénin back to 1959 with a couple of other bottles from my own cellar thrown in for good measure. Under the Despujol family, Nénin made sound and solid wines in the 1950s and 1960s before it lost its way. Nénin has been given a new lease of life under Jean-Hubert Delon who reorganized the parcels and cleaved away less propitious vines on sandier soils. You will find several other mini-verticals here, both from known château such as Batailley, Figeac, Grand Puy Ducasse and Château Margaux, and less well-known growths such as Château Haut Selve.

Stephane Derenoncourt, here pictured after the vertical tasting of Domaine de l’A in Berry Brothers & Rudd’s dining room

A couple more things. I maintain that the 2000 Mouton-Rothschild is an underwhelming First Growth whose quality goes little deeper than the eye-catching gold embossed bottle. Apologies for being so blunt. It was poured blind next to LVMH’s super-deluxe Chinese wine “Ao Yun” (passable but nowhere near that quality one expects from its asking price) and 2013 Opus One, the Californian easily the best of the trio.

I have also included here a vertical of Stéphane Derenoncourt’s Côte de Castillon, Domaine de l’A, back to the maiden 1999, which was raised entirely in new wood since he had no used barrels. Probably the best value of any wine mentioned here, presented by Derenoncourt at agents Berry Brothers & Rudd, evinced how well Domaine de l’A can age, though I prefer more recent vintages without the Cabernet Sauvignon. Derenoncourt explained how he practices a little carbonic maceration because it renders less dryness and makes the wine more homogenous and easier to extract. He also cited the 2005 as a turning point, when he added six-hectares on limestone soil to the original parcel to engender a rounder and more saline wine.

Last but not least – Sauternes! Everybody knows I get all starry-eyed over Sauternes. Over the years I have conducted a vertical tastings at all the major properties within this auric appellation and I will be furnishing Vinous with plenty of “golden” tasting notes that everyone will doubtless ignore. That will not prevent me from preaching the mellifluous brilliance of Sauternes, young and old. The 1949 Climens, served after a magnificent vertical of Christophe Roumier’s Bonnes-Mares, was an appropriate way to finish the evening, thanks to its breathtaking concentration and liveliness that was undimmed after almost seven decades, surpassing in my view, the much-touted 1947 Climens. If you want outstanding value, a bottle of 1971 Coutet that was astonishingly fine, so vivacious and full of intensity and tension that you could barely believe it to be 47 years old.

That’s all for this round up. The next Cellar Journal will shift towards Burgundy.

You Might Also Enjoy

Looking Back To Go Forward: Lafite-Rothschild 1868 – 2015, Neal Martin, July 2018

In Excelsis: Château Latour 1887 – 2010, Neal Martin, July 2018

Bordeaux In Excelsis, Neal Martin, June 2018

Last Man Standing: Bel-Air Marquis d’Aligre, Neal Martin, May 2018

A Century of Bordeaux: The Eights, Neal Martin, May 2018

Purple Reign: La Conseillante 1966-2015, Neal Martin, May 2018

The F-Word: Bordeaux 2017, Neal Martin, April 2018

Show all the wines (sorted by score)

- Batailley

- Bélair-Monange

- Beychevelle

- Calon Ségur

- Chasse-Spleen

- Château Margaux

- Cheval Blanc

- Climens

- Clinet

- Clos de Sarpe

- Coutet

- de Pez

- Domaine de Chevalier

- Domaine de L'A

- Figeac

- Giscours

- Goujon

- Grand-Puy Ducasse

- Gruaud Larose

- Guiraud

- Haut-Brion

- Haut Selve

- Lafite-Rothschild

- Lafleur

- La Louvière

- La Mission Haut-Brion

- L'Arrosée

- Latour à Pomerol

- La Tour de Mons

- La Violette

- Léoville Las Cases

- Lynch-Bages

- Magdelaine

- Meyney

- Montrose

- Mouton-Rothschild

- Nénin

- Pavie

- Pontet-Canet

- Siran

- Talbot

- Troplong Mondot

- Trotanoy

- Trotte Vieille

- Valandraud

- Vieux Château Certan