Browse using the new Vinous website now. Launch →

Printed by, and for the sole use of . All rights reserved © 2015 Vinous Media

Setting Sail - Malartic-Lagravière 1916-2013

BY NEAL MARTIN | APRIL 2, 2019

Growing up in a sailing family, I spent many a Sunday crossing the Thames Estuary with my father and any conscripted siblings. It was fun clinging to the rigging with legs dangling over choppy, foaming waters, even if I never did persuade Dad to sail all the way to France. Nowadays, much of my life centers upon another estuary, the Gironde in Bordeaux. Here, one can find a property whose history is nautically entwined: Malartic-Lagravière. But the voyage of this Pessac-Léognan has not always been plain sailing. Over the years, it has encountered rough seas as well as periods when it drifted aimlessly through the doldrums and almost ran aground. Thankfully, in the 1990s the property found a fine Belgian captain who has navigated a safe passage to calmer waters, and Malartic-Lagravière is presently one of the finest vessels among the fleet of Bordeaux châteaux. Last year I visited the estate to find out about its history and conduct a vertical tasting. So let us cast off and begin by looking at its origins.

Château Malartic-Lagravière.

History

The origins of Malartic-Lagravière stretch back to a time before the French Revolution when the estate was known as Domaine de Lagravière, for its gravel soils. In 1803 it was bought by Pierre de Malartic, the nephew of Comte Hippolyte de Maurès de Malartic, an admiral who scored a famous victory over the British at the battle of Quebec in 1756 and later became governor of Mauritius. Some time in the 1840s, Pierre de Malartic’s son Jean Ernest Malartic sold the estate to Auguste Thibaudeau, whose tenure lasted only a couple of years. Here, facts become sketchy. Clive Coates MW believes that Mme. Angele Ricard, who took over the estate in 1850, was born Thibaudeau, since Auguste's ownership was so brief. It does seem more likely than her purchasing the property outright, since those were misogynistic times. Then again, Mme. Ricard was known as "le grand homme de la famille," so maybe not. Two facts that are true: she prepended the surname of the estate’s erstwhile proprietor, changing Domaine de Lagravière to Malartic-Lagravière; and in 1860 her son Jean Ricard acquired Domaine de Chibaley, which became Domaine de Chevalier.

Strangely, I can find no mention of either Malartic-Lagravière or Domaine de Lagravière in the 1874 edition of the Féret guide, though in the 1898 edition, Jean Ricard is listed as owner of three Graves crus: Malartic-Lagravière, Domaine de Chevalier and de Fieuzal. Malartic-Lagravière is recorded as a 35-hectare vineyard producing 45 tonneaux per annum, the same as Domaine de Chevalier. In 1908, Jean Ricard passed away and the estate went to his son-in-law, Lucien Ridoret, whose family came from Cambes. They were mariners, which is why Ridoret’s galleon, the Marie-Elisabeth, was depicted on the label. Ridoret’s seafaring life meant that in all likelihood, his wife looked after daily running of the vineyard and oversaw the oldest wine included in this article.

André succeeded his father in 1929, and his only child, Simone, eventually married Jacques Marly, who became proprietor in 1947. (One interesting aside – again courtesy of Clive Coates – is that Marly's ancestors once owned a vineyard now occupied by Merignac airport.) Marly’s main business was manufacturing mirrors, and this inspired the labels of the 1962 and 1964, both decorated with mirror images of the name. Authorities banned its continued use, since apparently some customers thought it was written in Russian, which is easy to understand if you examine the image below.

The "mirror labels" were used in just two vintages.

Jacques Marly was a deeply religious gentleman who considered everything to be a gift from God, from his large brood of offspring to bountiful fruit on the vine. Consequently, notions of contraception and low yields were anathema. There is a telling passage in Hubrecht Duijker's book The Great Wine Châteaux of Bordeaux in which Marly is quoted as saying, “We are always the odd ones out, refusing to go with the crowd!” He then propounds that quantity and quality can go hand in hand, ruing having to declassify when he exceeds the legally permitted yield. Indeed, yields in Marly’s time were excessive. The white was picked at 11° alcohol by rote and chaptalized, while both white and red were routinely aged in 100% new oak. At that time the chai was located elsewhere, in the center of the village, which would have caused more disturbance to the wine. Marly had ten children, and his youngest, Bruno, took over running the estate in the 1980s. The former accountant had to be coaxed back into the family business, suggesting that winemaking did not exactly course through his veins; ergo, many bottles from this period are distinctly run-of-the-mill. In 1990, Marly retired and the estate was sold to the de Nonancourt family, owners of champagne house, Laurent-Perrier, a precursor to the Rouzaud family of Louis Roederer's acquisition of Pichon-Lalande in 2006. Unlike the Rouzauds, their heart was never really in it and in retrospect they should have appointed a dedicated technical director instead of allowing Bruno Marly to continue.

Alfred and Michèle Bonnie.

Inevitably, Malartic-Lagravière was put on the market. In September 1996, a Belgian couple, Alfred-Alexandre and Michèle Bonnie, took a second tour of the property, having already viewed around 50 estates. They wanted to be sure of their choice, and so they brought along their son Jean-Jacques, who was waiting to do his military service. On February 6, 1997 the Bonnies signed the contract and opened a new and more settled chapter of Malartic-Lagravière. I have only met Alfred-Alexandre Bonnie a couple of times, but I do remember an entertaining evening at the château with an ongoing joke about James Bond; God knows exactly how that came about. I asked his daughter-in-law Séverine Bonnie whether her father-in-law had always harbored an interest in wine. "When he was a child, Alfred spent time with his father putting the family cellar in order. He became fascinated by fine wine: Burgundy, Champagne and Bordeaux. Traditionally in Belgian families there is always a good bottle of wine for Sunday lunch. Alfred and his eldest brother Edgar were given permission to drink one glass and they found it was like nectar. Chez Bonnie, the wine of choice was good Bordeaux, and Alfred recalls a fabulous bottle of 1961 Cheval Blanc. After what you might call his first career, he had the idea to change his life and come to Bordeaux to make wine. Alfred and Michèle Bonnie started to look for a vineyard around 1995 and finally fell in love with Malartic-Lagravière, a sleeping beauty."

Philippe Garcia soon replaced Marly, while Denis Duboudieu consulted for the whites until 2000, Michel Rolland for the reds. Laurent-Perrier had only invested in the vineyards, so architect Bernard Mazières, who had designed d’Yquem and Château Margaux, was hired to oversee the new winery, which became operational in 1999 (see below for details). Alfred Bonnie also redesigned the label and continued the maritime theme. From 1996 onward, the Marie-Elisabeth was replaced by La Minerve, a vessel that had belonged to the Comte de Martillac.

Séverine, Jean-Jacques and Véronique Bonnie. Judging by Jean-Jacques' teeth, this must have been taken after our vertical.

In 2003, Jean-Jacques Bonnie and his wife Séverine joined his parents in running the estate. That same year, they also acquired a neighboring property, Gazin-Rocquencourt. "I was born in Paris, just like Jean-Jacques," Séverine Bonnie told me. "My parents are not involved in the wine business, although my father has a country house in northern Burgundy. Jean-Jacques and I met in 1994 at a business school in Champagne, and we graduated in June 1996 when my parents-in-law were about to buy Malartic-Lagravière."

The Bonnie family have expanded their horizons beyond Bordeaux, looking further afield and introducing a Mendoza wine, DiamAndes, from Clos de Siete. In the last three years, Alfred and Michèle Bonnie have stepped back from daily management, although they keep a careful eye on the property. In 2006, Jean-Jacques’ younger sister Véronique joined the team, and she now runs the financial and administrative side while her brother focuses on the technical, commercial and winemaking parts of the business. Véronique’s husband Bruno arrived in 2010 and works on the commercial side of Gazin-Rocquencourt and the Argentinean wines, while Séverine herself is responsible for communication and marketing. I can think of few other Bordeaux estates that proactively promote their wines around the world.

Vineyard

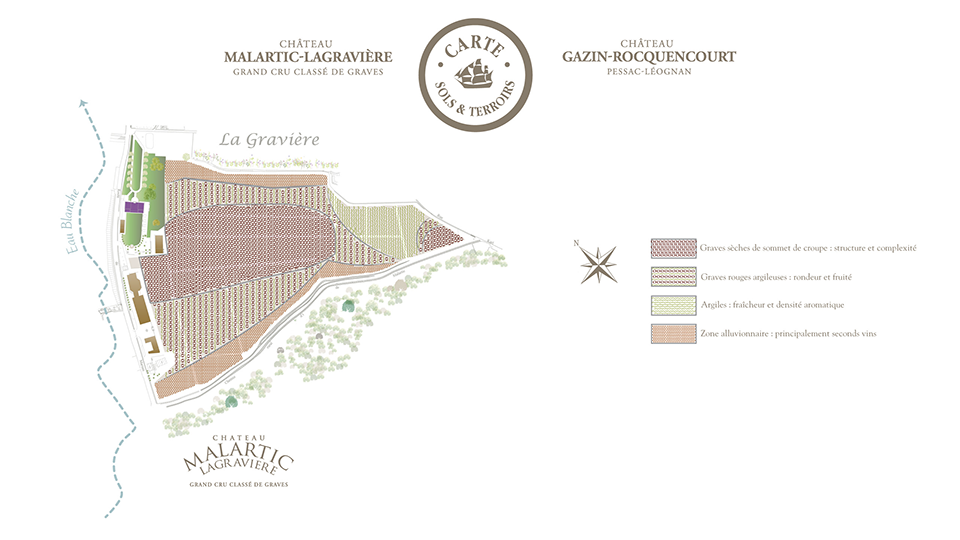

Located just south of the town of Léognan, the vineyard covers a total of 53 hectares – 46 hectares of red and 7 hectares of white. As the map illustrates, the vines are not in a single block. However, all the parcels are in the commune of Léognan, within a 750-meter radius of the village. The vines populate an eight-meter Quaternary gravel terrace formed by the Eau Blanche creek. Underneath lies limestone subsoil high in fossil content, with veins of clay that are beneficial in drier growing seasons because they retain moisture. Benoit Prévoteau, chef de culture since 2003, approaches the vineyard plot by plot. "In terms of breaking down the parcels, the first criteria are the nature of the soil and subsoil, as you see on the map," Séverine Bonnie explained.

The vineyards at Malartic-Lagravière.

The proportions of grape varieties are 45% Merlot, 45% Cabernet Sauvignon, 8% Cabernet Franc and 2% Petit Verdot for the red, and 80% Sauvignon Blanc and 20% Sémillon for the white. The Bonnie family introduced Sémillon when they reconstituted the vineyard in the late 1990s, something to bear in mind with respect to the older vintages, which are pure Sauvignon Blanc. In addition, some parcels use high-density plantings of up to 10,000 vines per hectare. The vines average around 30 years old and are pruned double-Guyot, except for the Sémillon, which is taille à Cot. They grow on three rootstocks: a majority of 101-14 due to its quality and the penetration of its roots deep into the soil, plus some Riparia and 3309.

I asked Séverine Bonnie to tell me about pest control in the vineyard, mitigating disease pressure, tackling esca and so forth. "Since the family arrived, the environment has become a major concern. Alfred and Michèle Bonnie initiated this work, and when Jean-Jacques arrived in 2003, he took it further. We earned the sustainable certification in 2008 and HEV in 2015. Since then, the entire team has been deeply involved in this process." Jean-Jacques Bonnie explained how the vineyard sprayers are fitted inside tunnels that surround the vines in order to confine the spray and let any unused spray drain back into the tank. This system took three years to develop, but it has enabled the vineyard team to decrease the use of sprays by 30%. These days, around 80% of the sprays are organic. "The investment is huge, but it’s worth it for our vineyard, for our neighbors and consumers, and for us,” Bonnie told me. “Last year we also initiated a plan to be certified ISO 14001. That should happen in June 2019."

Although vineyard husbandry is divided into individual plots, this does not dictate how the fruit is picked. Instead, it is harvested according to soil type, vine age and so forth. This is partly because of the shape of the vineyard. In order for the vine rows to be straight and easy to tend, individual parcels are shaped like interlocking parallelograms that do not correlate to the differences in terroir. "For the reds, we usually have between 80 and 100 people for the harvest," Bonnie told me. "We harvest the whites only in the morning. The tannins must be ripe – it’s difficult to make good wine with green tannins. Fortunately, our vineyard is plowed, forcing the roots to go deep, and this promotes more stable hydric assimilation throughout the vegetative period. When it’s too rainy, the gravel soil drains out the surplus of water, and when it’s dry, the depth of the roots keeps providing freshness to the vines. Analysis shows that two or three weeks before the tannins are ready, there is an increase in sugar and an evolution of pH, as if these two parameters are stabilized before the tannins are ripe. So tasting the berries frequently, together with the vineyard manager and winemaker, tells us when the fruit is ready to be picked – when the greenness and angular sensation of tannins are gone, the fruit and concentration are present, and acidity maintains all of this high in the mouth.”

The modern vat room at Malartic-Lagravière.

Winemaking

The château was built in 1850 and has been fully refurbished with a Tuscan aesthetic. It houses an indoor swimming pool that I have nearly walked into on several occasions (apparently a waiter did walk straight into the pool in the past). The winery itself is located in a separate building. Bernard Mazières created an octagonal design that accommodates 20 stainless steel vats plus 10 wooden vats. The wine is transported within the winery entirely by gravity, using hoists to transfer the fruit from one place to another, in what is known as a douil system. Bonnie provided me with details on their winemaking approach.

"Since 2001, the fruit undergoes double sorting on a vibrating table de tris. We cool down the grapes in order to have them at around 10°C for a short pre-fermentation maceration, which usually lasts around five days. Then we let the temperature rise, which wakes up the native yeasts, but we keep it below 28°C. The idea is to extract as much as possible at the lowest alcoholic degrees and minimize extracting at higher levels of alcohol that can be more violent and give you undesirable rustic and solid compounds. We only conduct pumping over. We usually do around four per day, so that equals about one volume [of the vat]. When the alcoholic fermentation approaches completion, we just wet the cap, no more."

The vin de presse is graded into three to five different levels and usually comprises around 2–3% of the final blend, and never more than 5%. The wine is transferred into barrels that mostly come from Tronçais and Allier forests in central France, Fontainbleau and Jupilles in La Sarthe, and also a small forest, de Bercé, which is populated by sessile oak trees. The estate works mainly with the Taransaud and Demptos cooperages, but also Baron and Boutes, and there are ongoing trials of Surtep. The Grand Vin is matured in around 60% to 80% new oak.

"We produce about half Grand Vin and half deuxième vin," Bonnie told me. I asked whether a parcel or a barrel selection governs whether a particular lot will end up in the Grand Vin. She answered, “It’s a bit of both. Some plots are based on a less ‘deep’ terroirs and will always produce second wines. Some plots are top terroir but the vines are still too young for the roots to go deep enough and produce grapes with the density and complexity we look for. There are some terroirs that will occasionally enter the Grand Vin, depending on the growing season.”

As we worked through the white wines, I asked Bonnie about their modus operandi."We press at the lowest pressure possible, to maintain freshness. We apply very long pressurizing programs, usually around six hours for one press. Next, we put the must in barrel, where we do the debourbage as well as the fermentation. Then the wines age for about 12 months in barrel. Usually 100% of the Sémillon is matured in new oak, and about half of the Sauvignon Blanc. With respect to the Sauvignon Blanc, we use about one-third Bordeaux barrels, one-third Burgundy pièces and one-third 500-liter barrels. This is to impart structure and therefore longevity without oak aromatization. The relationship between Sauvignon Blanc and new oak can be complicated, which is not the case with Sémillon."

The Wines

This tasting focused on recent releases under the Bonnie family’s tenure, augmented by more mature bottles from their cellar and a handful of very old bottles that I encountered at the Académie du Vin dinner in Bordeaux.

One of the most profound bottles from the early 20th century that I have encountered.

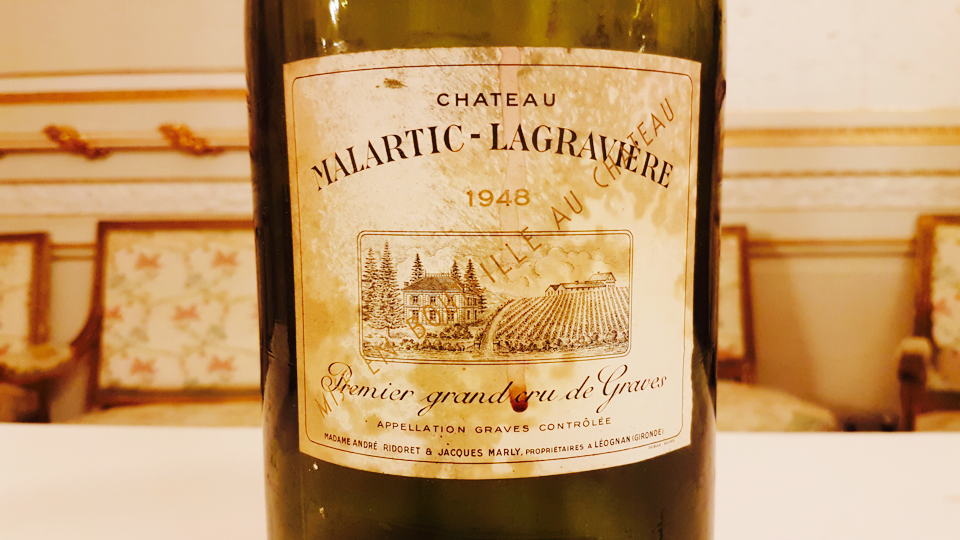

The oldest bottle here is the otherworldly 1916 Malartic-Lagravière, produced when Lucien Ridoret was proprietor. Considering it was made amid World War I, it is a testament to the fortitude of those laboring in the vines at that time, making do with rudimentary materials. I vividly recall gawping in disbelief and hesitating to inhale the nose, an intoxicating mélange of Bordeaux and Burgundy that shows incredible purity. Maybe it was a one-off, since another bottle was not of the same caliber, but the experience is indelibly printed on my memory. The handful of wines I have tasted from Jacques Marly’s tenure in the 1940s and 1950s have been reasonably good, particularly the whites, as demonstrated by the sublime 1948 and 1953 Malartic-Lagravière Blanc. The wines never reached their full potential in great vintages like 1945 and 1961, which dented the estate’s reputation, despite being bolstered by the Graves classification in 1953. Malartic-Lagravière never “kicked on” and strove higher like Domaine de Chevalier, which was a much more consistent château in that era.

From the 1960s to the 1990s, great wines are few and far between. Publications like this one should always advise readers on what to avoid as well as what to seek out, and certainly this period saw a significant drop in quality. The 1970s can be excused because of the succession of poor growing seasons, but the 1980s provided ample opportunities to craft far superior wines. Yet subpar releases continued and the estate fell behind the pack of evolving Pessac-Léognan properties. Right into the 1990s, I find the wines ordinary, and they occasionally betray faults suggesting wrong decisions in both vineyard and winery, as evinced by a woeful 1995 Malartic-Lagravière.

The golden age of Malartic-Lagravière is not in the past – it is now. In particular, the long-overdue new winery gave the estate equipment befitting its terroir. Under Alfred-Alexandre Bonnie and now Jean-Jacques, there is an aspiration to create a top-performing Pessac-Léognan and achieve far greater consistency. The whites often have a scintillating acidity, a sense of brightness and vivacity that distinguishes Malartic-Lagravière from its peers, often with a trace of honey toward the finish that reduces the risk of shrillness. The turnaround for the reds began in the late 1990s. The wines often develop black fruit infused with bay leaf and tea leaf scents, and they are predominantly classic in style and predisposed to cellar aging. For the whites, there seems to be a propensity to knock the ball out of the park in even-numbered vintages: 2006, 2008, 2010 and 2012 Malartic-Lagravière Blanc are all wonderful dry white Bordeaux that will give two decades of drinking pleasure, possibly more. Prior to that, as I mentioned, you have to go back to the 1940s and 1950s, although the 1987 proves that the Marly family could create good wines when they wanted to. With respect to the reds, the 2009 and 2010 Malartic-Lagravière excel; likewise a sterling effort in 2012 that compensates for a rather lackluster 2013. The 2005 Malartic-Lagravière is good but rather foursquare and, in my opinion, surpassed by subsequent vintages.

Final Thoughts

Malartic-Lagravière has weathered rough seas in its history. Nowadays, as proven in numerous blind tastings, they are producing excellent wine both here and at neighboring Gazin-Rocquencourt. Furthermore, as with many Pessac-Léognan wines, prices have remained reasonable, and in terms of value, Malartic-Lagravière comes highly recommended. The investments under the Bonnie family have transformed the estate from one that lagged behind its peers into one of the front-runners not just within the appellation, but in Bordeaux. My one unfulfilled wish is that they would reintroduce that ingenious "mirror label" they used in the 60s. Please? Just for Vinous readers?

See the Wines from Youngest to Oldest

You Might Also Enjoy

What Nectar!! Suduiraut 1899-2015, Neal Martin, March 2019

A Test Of Greatness: 2009 Bordeaux Ten Years On, Neal Martin, March 2019

Outsider Looking In: Sociando-Mallet 1982-2015, Neal Martin, March 2019

Looking The Part: Pichon-Baron 1953 – 2015, Neal Martin, January 2019