Browse using the new Vinous website now. Launch →

Printed by, and for the sole use of . All rights reserved © 2015 Vinous Media

Looking The Part: Pichon-Baron 1953 – 2015

BY NEAL MARTIN | JANUARY 30, 2019

There is a certain type of person who wears a bow tie beyond a tuxedo. It is a sartorial accoutrement that distinguishes its wearer from “the rest,” not dissimilar to those who wear a pince-nez rather than spectacles, or braces [suspenders] rather than a belt. The bow tie makes a statement about its wearer, something along the lines of, I got a bow tie and I’m gonna wear it. I came across the following quote on the Internet: “Wearing a bow tie is a way of expressing an aggressive lack of concern for what other people think.” “Normal” people who make do with common-or-garden neckties feel subconsciously challenged by the bow tie. What does it infer about that person? This man is eccentric. This man is old-fashioned. This man must be a university don. This man is a twit. This man is upper-class. This man is a narcissist. And so forth. These assumptions are all unfounded and doubtless incorrect. Just look at the eclectic bunch of bow-tie aficionados: Karl Marx, Stan Laurel, Charlie Chaplin, Sir Winston Churchill, Malcolm X, Keith Floyd, Hercule Poirot, Alfred Kinsey, Pee-wee Herman and Waylon Smithers. On reflection, whilst they lived wildly differing lives, maybe that “aggressive lack of concern for what other people think” is the common thread running through all those personalities.

Pichon-Baron's château building

Is that true with respect to Christian Seely? In the two decades that I have known him, I have never seen him without bow tie. It is synonymous with his name. Seely is to bow tie what Superman is to red cape. Maybe without it, he would lose his power and all his wines would turn to vinegar? On one occasion, I made an emergency stop at Pichon-Baron to ask if Seely could sort out my bow tie because, despite all instructions and “It’s So Easy” YouTube tutorials, I could not and cannot knot one myself. To me, Seely’s bow tie symbolizes a man who furrows his own path. Though salaried by AXA Millésimes, a subsidiary of a multinational insurance company, Seely calls the shots, a bridge between artisan winemaking and corporate worlds. With Domaine de l’Arlot in Burgundy, Quinta da Noval in the Douro, Château Petit-Village in Pomerol, Château Belles Eaux in Languedoc, Disznókő in Tokaj, Outpost in Napa Valley and Pichon-Baron under his aegis, he must adapt his approach according to the estate and market. AXA Millésimes’ policy was always to buy estates with unfulfilled potential, so the task set before any manager is manifold: reorganizing vineyards, investing in wineries, appointing the right people, keeping hold of the right people, dealing with foreign markets, repositioning the brand and setting prices, inter alia. Pichon-Baron is no exception. It requires a long-term strategy and a single person to see it through.

The journey that Pichon-Baron has taken in the last four decades has been truly remarkable. This article examines Pichon-Baron (and I will use its common name rather than “Château Longueville au Baron de Pichon Longueville”) and its sibling, Château Pibran, from the postwar period under the Bouteiller family to its purchase by AXA Millésimes and the tenures of Jean-Michel Cazes and Christian Seely. It covers its Damascene resurrection from perennial underachiever to bone fide star of the Left Bank. Underpinning everything are the wines, and so this report includes one of the most comprehensive vertical tastings conducted in recent years.

Christian Seely in the dining room at Pichon-Baron

History

As their names imply, Pichon-Lalande and Pichon-Baron are twins born from the same estate. Their genesis is the land that Pierre Rauzan purchased close to Latour, once known as L’Enclos Rauzan. It was here that Rauzan planted the first vines, just as he had done down south in Margaux. Three women – Rauzan’s daughter Thérèse, Germaine de Lajus and Maria Branda de Terrefort – were instrumental in building the foundations of the Pichon-Longueville estate. When Rauzan died in 1692, his 20-year-old daughter Thérèse inherited the land as part of her dowry to Jacques-François de Pichon. Her husband pursued a military career whilst Thérèse, already a dab hand at vineyard management, took over the running of the estate in 1697 and continued her father’s prescient strategy of acquiring adjoining parcels. Thérèse passed away in 1746, but within five years, the wife of her grandson, Germaine de Lajus, was at the helm of a productive, forward-thinking estate. With the barons seeming to fall like flies, Maria Branda de Terrefort ran Pichon from 1761 until 1777.

There was a male interregnum under Baron Joseph de Pichon-Longueville. During his tenure, the estate was relatively unscathed in the Revolution and subsequently its wines began to reach Deuxième Cru prices. However, the Revolution did impact inheritance laws. When the 99-year-old Baron died in 1849, his 50-hectare estate was split equally into five. Raoul was the only surviving son and inherited the baronetcy, plus two-fifths or 28 hectares of the estate, including the share allocated to Louis, a sibling who had died in 1835. Raoul’s three sisters inherited the other three-fifths. Despite this division, it continued to be run as a single estate. Raoul constructed the château in 1851 to replace the maison noble known as “La Baderne” that had stood for three centuries. It was only upon his death in 1860 that the wines began to be made separately (though legal separation was not until 1908). Raoul bequeathed Pichon-Baron to his identically named cousin, leading one to assume that there must have been a shortage of names in 19th-century France. The Pichon-Longueville dynasty lasted until 1933, whereupon the estate was sold to Jean Bouteiller, whose family were direct descendants of Louis XIV and whose brother, Hubert, ran Château Lanessan. Jean Bouteiller ran the estate until he died in 1961. I will halt the timeline at this point since this is where our exploration of wines will begin.

The Vineyard

The present vineyard includes 70 hectares of vine located between the château building and Saint-Julien. The composition of grape varieties includes 60% Cabernet Sauvignon, 35% Merlot, 4% Cabernet Franc and 1% Petit Verdot, although those figures are misleading because the final blend usually contains around 80% Cabernet Sauvignon, planted on the gravel croupe. Much of the Merlot, planted on more ferrous clay/sandy soils, is relegated to the second label. Seely once told me that for two years they had experimented with not applying copper sulphate in the vineyard, but the results were not as expected and so they just use the minimum amount.

I asked vineyard manager and cellarmaster Jean-René Matignon about the pruning method used at Pichon-Baron. “We use the Guyot Médocaine or Guyot Poussard method. All grapevine trunk diseases concern us: Esca, Eutypa dieback, etc. We try to reduce the inoculum sources by destroying diseased vines. This is what led us to incinerate the prunings. We are going to abandon that in favour of composting.” I also asked whether there had been changes in the vineyard in terms of grape varieties. “The varieties are planted according to the terroir: deep gravel deposits for Cabernet Sauvignon, cooler areas for Merlot and clay for Cabernet Franc. Petit Verdot is being tested in a top terroir. Alcohol percentage no longer being a constraint, Merlot, which tends to be richer, is less necessary than it was 20 years ago. We are testing a collection of Cabernet Franc, which could be expanded if we replace the Merlot. Rather than changing variety, we prefer the idea of adapting the way the vineyard is managed. There’s still progress to be made.”

Readers should note that a video of Christian Seely explaining the map of vineyards in Pauillac can also be accessed on the Multimedia page on Vinous.

The Winery

In the introduction to my Cos d’Estournel article, I declared that one of the most striking vistas in Bordeaux is the twin Pichons gazing at each other on the crest of the gravel croupe as you exit Saint-Julien. Constructed by Charles Burguet in 1851 in a neo-Renaissance style, Pichon-Baron vies with Palmer as the most fairytale in style, with its splendid slate witch’s-hat turrets. Its architectural symmetry is mesmerizing, not just horizontally but vertically, since the château is reflected in the rectangular ornamental pool out front. It seems difficult to believe that for half a century the château building was basically a shell, uninhabited by the Bouteiller owners, though for a period of time it was rented out to the Rotary Club of Pauillac. Upon AXA’s acquisition, the entire château was completely refitted and looks good as new, though nobody calls it home as such.

Pichon-Baron's pool

The winery hides below ground. I will detail the deplorable conditions of the former winery in the 1950s and 1960s later. Let’s just say it was unbefitting a Second Growth. In 1986, AXA announced that they would hold an architectural competition to design a winery, overseen by the Centre National Georges Pompidou. The winning design integrates discreet Egyptian flourishes that almost completely disguise the entrances from a frontal viewpoint. The chai lies underneath, a circular design like at Lafite-Rothschild, with columns supporting the roof. Apart from the hygiene and practicality of the design, the new winery simply offers more space. Matignon recalled that the old winery necessitated stacking the barrels four tiers high, whereas in the new winery they are stacked two high.

I asked Matignon about the harvest at Pichon-Baron and his opinion about optical sorting. “We tested sorting bunches both before and after de-stemming in 2002, a year with millerandage, and then fully introduced it in 2003. We have used optical sorting since 2009. We examined it in comparison with manual sorting, which is tedious work, and judged it to be at least equally efficient. The idea is to limit the number of affected grapes being vinified and to limit the use of sulphur. We prefer to adapt vinification to the terroir and to the vintage rather than to the state of the harvest!”

I then asked about the tenets applied to the alcoholic fermentation. “As with all our vineyards, we do not follow a formula,” answered Christian Seely. “I encourage our winemakers to use their professional judgement and their artistic instinct for the vinification of each parcel as it arrives on the winery.” As an aside, Seely emphasized this when tasting with Géraldine Godot, winemaker at Domaine de l’Arlot. Jean-René Matignon continued: “For the top terroirs, we prefer traditional vinification patterns for a three- or four-day period at 10–15° Celsius, followed by fermentation at 25–28° Celsius and a post-fermentation period at 26°C until running off. Extraction is by pumping over with one or two délestages mid-fermentation. At the end, and after fermentation, decisions depend on tastings. We are sparing with punching-down, which is reserved for the top terroirs vinified in wooden vats.”

Then I asked about the cooperages. “We work in collaboration with six coopers to define our requirements,” Matignon replied. “For us, a great barrel is defined by its low profile. The wine is the priority. Great origins [of barrels] are often the most interesting and the most costly, especially for extra-fine grains. The degree of toasting is adapted to the vintage, allowing us to refine our choices.”

Apart from the Grand Vin, the estate also produces their well-known second label, Les Tourelles de Longueville. There is also another cru, Les Griffons de Pichon-Baron, that was launched in 2012. “Since the strategic decision was taken in 2001 to make a much stricter selection for the Grand Vin, focussing on the grand terroir of the plateau at the heart of the property, we have produced a much higher volume of second wine than before, inevitably of very high quality since many of the parcels now making our second wines were previously used for the Grand Vin. We decided to launch Les Griffons in order to bring out the individual character of the various terroirs used to make our second wines. Les Griffons is our Cabernet Sauvignon–based second wine, tending to be a blend of around 60% Cabernet Sauvignon and 40% Merlot, whereas Les Tourelles tends to be around 60% Merlot, and the rest Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Franc, and Petit Verdot.”

Opening Act: Château Pibran

Let us take a quick break from Pichon-Baron. During my visit, I asked Christian Seely if we could include a tasting of Château Pibran. Gentleman that he is, he kindly obliged and opened the last decade of wines. He was pleased that I had requested an overview because Pibran lingers in Pichon-Baron’s shadow. That is a pity. Apart from representing great value for money, in my opinion, its quality punches above its reputation. Whilst not as complex as Pichon-Baron – with one notable exception, as I shall reveal – nothing suggests that Pibran cannot offer two decades of drinking pleasure in a good seasons.

The Billa family purchased Pibran in 1941, Paul Billa recorded as proprietor in the 1949 edition of Féret, where it is listed under Château La Tour Pibran, owned by the Gounel family for many years. Seely mentioned that the original proprietor was a military aviator. “AXA Millésimes bought Pibran in 1987,” Seely told me. “It consists of scattered parcels north of Pauillac, some neighbouring Pontet Canet and Grand Puy Lacoste. In 2001 we bought Château Tour Pibran, a direct neighbour, whose parcels intermingled with Pibran. After 2001, Château Pibran comprised a selection of parcels from both the original Pibran and Tour Pibran, since we found there are grade “A” and grade “B” parcels within each estate. We use “Tour Pibran” as the name for the Second Wine, though it is not sold en primeur.” Enquiring whether there is a difference between the terroir of Pichon-Baron and Pibran, Seely replies that Pibran has a colder terroir due to a higher percentage of calcaire. Pibran is usually aged for 12 months in one-year-old barriques, overseen by Jean-René Matignon.

The vertical affirmed my affection for Pibran and sprang up a couple of surprises, not least the outstanding 2007 Pibran that (whisper it quietly) challenges the supremacy of that year’s underperforming Pichon-Baron. Certainly, there are a couple of vintages that do not quite cut the mustard, such as the 2008 Pibran. And vexingly, three bottles of the 2010 Pibran were martyred before we found a bottle without taint. Recent vintages have been exemplary, the 2012 Pibran perfect for drinking now, the last three vintages of 2014, 2015 and 2016 all quite superb. All relevant tasting notes can be viewed in the accompanying link.

Main Act: Pichon-Baron

Technical Director Jean-René Matignon in the Pichon-Baron tasting room

Now back to Pichon-Baron. Last May I met with Christian Seely, Jean-René Matignon and communications director Corinne Ilic to undertake a vertical for which I put no limit on the number of vintages I would taste; that was left to their discretion. Seely was casually dressed: tweed jacket, off-duty jeans and regulation bow tie. He seemed to be itching to conduct a comprehensive vertical and had lined up an uninterrupted run from 1982 to the present day. The wines signpost Pichon-Baron’s journey, the twists and turns that have led to its present status, where it nips the heels of the First Growth. Crowning glories aside, it is important to include off-vintages, since they tell their own side of the story, and offer a more accurate litmus test than benevolent growing seasons of how the château is performing. Every now and again, less revered vintages deliver above the growing season’s reputation and represent great value, maybe better than in auspicious years. This was to be no different.

Quality never seemed to be at the forefront of Pichon-Baron’s mind during the postwar period. The château building might be pretty as a peach, and yet wines during the 1940s and 1950s were rustic fare, sorely lacking the nobility expected of any self-respecting Grand Cru Classé. During this period, the wine endured excessive maceration, and even up until the 1980s, machine harvesters were used when others had long progressed to hand-harvesting. The winery was run down and outmoded, whilst the château building was dilapidated. The real problems began when Bertrand Bouteiller inherited the estate from his father, Jean, in 1961. “Bertrand Bouteiller was just 18 years old when he took over Pichon-Baron after his father died in 1961,” Jean-René Matignon told me a few years back. “You can imagine, many of the workers had been here for a long time, so they could be difficult for him to manage.” Bertrand Bouteiller was at the beck and call of recalcitrant workers who supposedly knew better, notwithstanding a lackadaisical maître-de-chai happy to cut corners. Apart from machine-harvesting, there was little temperature control during fermentation, and the wines were bottled out in the courtyard, often in the warm sunshine. A vicious circle of poor, often coarse wine, low prices and lack of investment ensued.

Seely

opened three older vintages: the 1959, 1960 and 1961 Pichon-Baron, incidentally

all served blind. The 1959 and 1961 are perfectly respectable, provenance

obviously playing a key role. They have held up well, particularly the 1959,

which can be exceptional in magnum. Yet, I would not rank them within the top

tier in either year. Several comparable châteaux,

including Pichon-Lalande over the road, produced better wine in 1961. Their

quality stems from the benevolent growing season rather than the winemaking. In

an alternate universe, 1960 Pichon-Baron would be a revelation. In this universe, it is moribund and of

curiosity value only.

Let’s skip the 1970s, because frankly, you’re not missing much. In retrospect, the 1980s was a period when Pichon-Baron was the student summoned to the headmaster’s room, following a succession of poor reports. The headmaster asks why such a gifted pupil is content to languish in the middle of the class instead of striving for the top. “We might not have the authority to strip you of your Second Growth status,” the headmaster warns, bending his cane. “But rest assured, your reputation is suffering. Many of your fellow classmates are upping their game. You had better pull your socks up.”

So we commence with the 1982 Pichon-Baron. I have seen some professionals comment that 1982 is a great wine. Trust me, it is not. This benchmark vintage produced a raft of stupendous Left Bank wines and Pichon-Baron is not one of them. Just rack up the 1982 Pichon-Lalande alongside to measure the gulf between the siblings - it is more than the width of the road that separates them geographically. As if to ram home that fact, this was a rare example outside the appellation of Margaux where I find the 1983 Pichon-Baron more worthy than the previous vintage. It is not a fantastic Pauillac by a long shot, but it offers a soupçon more precision and length. The 1984 Pichon-Baron is interesting because a) it is rarely seen b) I have never tasted it before and c) it is 100% Cabernet Sauvignon. Apart from that, there is no reason to go out and hunt it down.

From left to right, Technical Director Jean-René Matignon, Communications Director Corinne Ilić and, in the bow tie, Christian Seely

In 1985, the first step towards its revival was made: the appointment of Jean-René Matignon. He has been the constant at Pichon-Baron, an immense asset behind the scenes, the lynchpin who has acted as technical director from 1987 to the present day. He began to address areas where the estate was lacking, including less-than-perfect storage conditions that affected some of the 1982s. Success would not come overnight, since there was much to do. Both the 1985 and the 1986 Pichon-Baron are also-rans, and the less said about the 1987, the better. That year was significant in terms of proprietorship.

Purportedly against Bouteiller’s wishes, the family shareholders voted to sell Pichon-Baron to AXA Millésimes, and they duly installed Jean-Michel Cazes as estate director. Cazes brought in his right-hand man, Daniel Llose, to work alongside Matignon as technical director and régisseur, respectively. This was a crucial and assiduous appointment. Cazes was entering his imperial phase, when both Pichon-Baron and Lynch-Bages not only challenged the supremacy of the First Growths, but in one or two instances, surpassed them.

We should pause to consider the context at that time. Pichon-Baron owned 33 hectares of vineyard in need of some TLC and an uninhabitable château building in dire need of refurbishment. I dug up an old article that I penned some years ago following a tasting at the Masters of Wine, where Seely shed some light on this transitional period. “AXA were experimenting with new ways to work the vineyard. The 1989 Pichon-Baron was vinified in old cement tanks and chaptalized by two degrees. Before they were pushing the Cabernet Sauvignon for higher yields, indeed, the 1989 vintage was cropped at 60hl/ha. The 1990 was a huge vintage. Even the stakes bore grapes! With potential yields of 65hl/ha, there was a lot of green harvesting. The 1990 Pichon-Baron was actually vinified outside and chaptalized by one degree.” The 1989 and 1990 served notice that Pichon-Baron was back. They are so superior to any previous vintage that they could come from a different property. In all but name, they do. I have tasted both numerous times over the years and in 2018 they both remain triumphant wines with half-century life spans. In particular, the 1990 Pichon-Baron is one of the wines of the vintage, a flip-reverse of 1982, as the 1990 Pichon-Lalande consistently underperforms.

The 1989 and 1990 altered consumers’ perceptions of Pichon-Baron. It was back in the game, and with the new winery at their disposal… bring on the good times! Not so fast. This vertical altered my opinion of Pichon-Baron in the 1990s. I once regarded that decade’s wines as the beginning of a high plateau. Now I see them as stepping-stones towards the 21st century. They have not aged as well as I presupposed, hampered by a succession of difficult growing seasons at the beginning of the decade. Time has been unkind to the 1991, 1992 and 1993 Pichon-Baron. The dark horse of the decade is probably the commendable 1994, which has held up well over the last 24 years. I am a little underwhelmed by the follow-up. “When the 1995 Pichon-Baron was young, it was tannic and dry on the finish. I always hoped that the tannins would soften,” commented Seely ruefully, since that dryness has never seemed to go away.

The decade peaks with the 1996 Pichon-Baron, as it does with Pichon-Lalande. “I remember it was a fresh season,” Matignon told me. “We had a very good September. The ripeness just before the picking looked good and we could see the potential. We had some good weather during harvest but it was not stable, so we had to be flexible about the picking.” If you are going to choose one Pichon-Baron from the 1990s, go for this vintage, the only one that can hold a torch to the heights of the 1989 and 1990 or the 2000s.

On January 1, 2001, when most of us were recovering from New Year’s celebrations, Christian Seely looked in his bathroom mirror, knotted his bow tie and clocked in for his first day’s work, replacing the outgoing Cazes, who could now focus on Lynch-Bages. Seely is an ambassador par excellence. English-born estate managers such as Seely and former Rauzan-Ségla director John Kolasa, tend to balance their insider’s view with an outsider’s perspective. On one side, Seely is the quintessential Englishman, dapper with a bit of rural chic, and well spoken, as you would expect from a Harrow-educated boy and a Cambridge-educated man. He graduated from the prestigious INSEAD business school with an MBA and after a period working in investment banking, entered the world of wine in 1993 upon his appointment as managing director for Quinta do Noval. Of course, wine had always been part of his life, since his father James Seely is a well-known merchant and author on Bordeaux. The younger Seely had no choice but to become a francophile and bon viveur. I remember when Seely was guest speaker at Vintners Hall, recounting how, when he was 16, his father gave him 1955 Dow to drink at breakfast on Boxing Day before a shoot, the catalyst for his love of Port. He also described a 1961 Palmer enjoyed with his father at a “sleazy hotel,” though I did not want to enquire further (apart from the address.) He has charm by the bucket-load and wry wit that counterbalances the austere corporate side of company ownership, to the extent that many consider Seely the de facto proprietor.

The turning point was Seely’s conviction that the vineyard at Pichon-Baron needed a completely new approach. Up until 2000 the vineyards had expanded in piecemeal fashion, a parcel here and a parcel there, most notably a large holding towards Batailley called Ste-Anne. However, this drive for expansion diluted quality. Not all terroir is equal. The resulting inconsistency was reflected in the performances of the Grand Vin throughout the 1990s. Seely was convinced that the “balloon” had to be gradually deflated, and he instigated a long-term reconfiguration of parcels so that the Grand Cru would refocus upon what he terms the Grand Terroirs. Anything that did not come up to scratch would be designated for the second label. To put figures on that, the vineyards that comprise the Grand Vin have been reduced from 80% of total acreage to 50%. That might not make the accountants happy, but it unquestionably improved the wine.

As a result, Pichon-Baron is more consistent and full phenolic ripeness more attainable irrespective of growing season, borne out by the fact that whilst chaptalization was almost part of the recipe in the 1980s and 1990s, no Pichon-Baron has been chaptalized since 2001. There is one black mark: the 2007 Pichon-Baron is a disappointing wine by the standards they themselves had set. I would probably opt for the 2007 Pibran. Another tricky wine, but more successful, is the 2003 Pichon-Baron. “The problem was that we had no winter rain,” Seely explained. “So whereas we usually have 700 to 800mm per year, in 2003 we had just 250mm. We suffered some millerandage from the heat. But the old vines performed well because of their deep roots, whereas the younger vines, especially Merlot, were quite grilled. We made two passes through the vineyard in order to root out the shriveled grapes.”

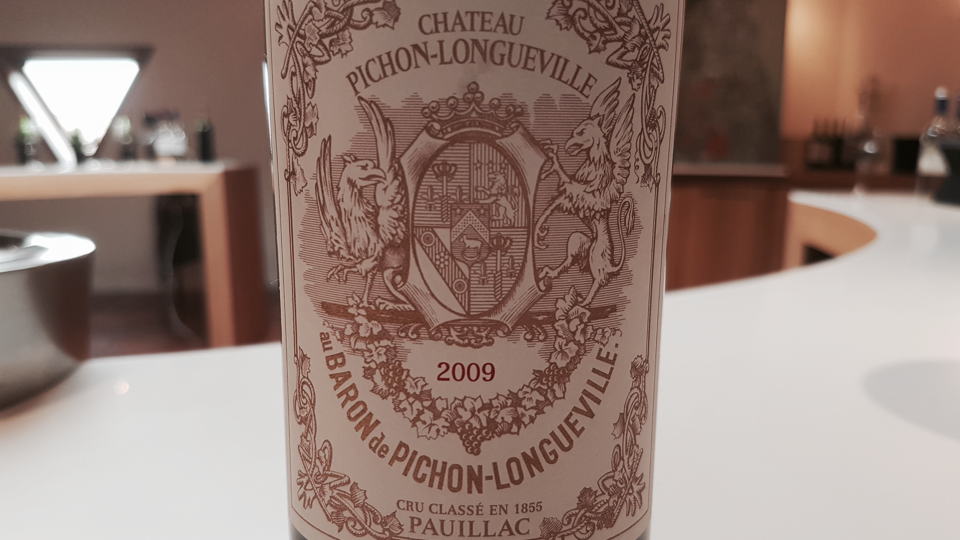

That aside, commencing with a deeply impressive 2000 Pichon-Baron, the decade is studded with a clutch of superb wines, not to mention a sense of reliability that has won Pichon-Baron a loyal fan base. A good example is the 2008 Pichon-Baron, which you would swear comes from a truly great vintage, equal to if not better than the high point of the 1990s. It is a precursor to the stunning 2009 Pichon-Baron. “It has gone back to its terroir in the bottle,” Seely commented, a smile on his face. In other words, it is losing its puppy fat. It is a magnificent Pauillac that will stand as one of the modern-day high points of the château. This is one of the few Left Bank wines where I prefer the 2009 to the 2010. The latter is a formidable beast of a wine that will last for decades, but the previous vintage has slightly better balance and more charm. It will be fascinating to see how they develop. The present decade has seen a continuation of Pichon-Baron as one of the most reliable performers; the triumvirate of 2014, 2015 and 2016 are all top-class.

Final Thoughts

Pichon-Baron is one of the lynchpins of Pauillac. Whilst the three First Growths might attract the headlines and glamour, the fact is that they are priced beyond the budgets of many wine-lovers. Despite price increases, Pichon-Baron is relatively affordable. This illuminating vertical clearly showed the stages of its renaissance. Without doubt, honing in on the gravel croupe for the Grand Vin (and relegating others to the second wine or Les Griffons de Pichon-Baron) is fundamental to its success, engendering a wine with greater purity, finer tannin, greater freshness and less rusticity. Now it looks the part. In many ways, perhaps alongside Grand Puy-Lacoste, it is the quintessential Pauillac. (Though Pichon-Baron is often compared with Pichon-Lalande, they are two very different wines that are perhaps beginning to merge a little more stylistically as Pichon-Lalande focuses more towards Cabernet Sauvignon.)

Naturally, I had to ask Seely where his affection for the bow tie comes from.

“My father always wore a bow tie, so I grew up associating normal ties with school, which I hated, and bow ties with my father, whom I loved. As soon as I was free to choose, I wore bow ties, always from Charvet in Place Vendôme, even when I could only afford one. They are the best by far. My father taught me how to tie one around my knee when I was about eight. I have never possessed a clip-on bow tie. For some years, I would occasionally wear normal ties just for a change, but people used to ask me if I was feeling unwell, and I realised that I had a duty not to disappoint expectations and abandoned that idea.”

Let us finish on that original quote. “Wearing a bow tie is a way of expressing an aggressive lack of concern for what other people think.” Of course, Seely and the team at Pichon-Baron care what consumers think about their wine, but at the same time, you need dogged determination to chart your own course and, from time to time, ignore what skeptics might think. When Seely proposed his paymasters relegate a swath of parcels that they themselves had green-lighted into the less-profitable second wine, I am certain that members of the board began to question their appointment. And I like to imagine that as the board considered voting down Seely’s proposal, they took one look at his bow tie, and then thought better of it.

See the Wines in the Order Tasted

You Might Also Enjoy

The DBs: Bordeaux 2016 In Bottle, Neal Martin, January 2019

Long Distance Runner: Brane-Cantenac 1924-2015, Neal Martin, January 2019

Enigma Variations: Lafleur 1955-2015, Neal Martin, November 2018