Browse using the new Vinous website now. Launch →

Printed by, and for the sole use of . All rights reserved © 2015 Vinous Media

A Century of…Fives

BY NEAL MARTIN | JUNE 17, 2025

My annual “Century of…” article revisits vintages on their decennial anniversaries. For many years, I tethered vintages to a contemporaneous timeline of music, since nothing evokes a sense of time like a melody. For a change, last year, I decided to tie vintages to FA Cup Finals. This year, it is literature’s turn—books published in years ending in five, Poe to Kafka via Tolkien and Murakami. The main wellsprings of tasting notes are 2005s opened at Burgundy domaines last autumn and then at Bordeaux châteaux during primeur. Older notes are culled from the Académie du Vin dinner and the “five” dinner held at Domaine de Chevalier. These are augmented by various other events, including Jordi’s 50th birthday lunch at Nando’s, a 1985 dinner at Noble Rot and Meerlust’s half-century anniversary, all in London. Readers can expect another tranche of 2015s from the South Africa blind tasting, but those will form a standalone piece. I hope you enjoy this as much as I enjoyed writing it.

1845 – “The Raven” – Edgar Allan Poe

Published on January 29, 1845, Poe’s narrative poem “The Raven” boils down to some bloke sitting by a fire moaning on about the loss of his love…to a bird. No need to tell you what type of bird. I empathise with the man who put the Poe into poetry. After a tough day in the office, I often return home and let off steam at the pet budgie. The Raven made Poe a celebrity, later inspiring Baudelaire, Nabokov and the American football team, the Baltimore Ravens. They are surely thankful to be named after Poe’s most famous poem instead of Nabokov’s most famous book, “Lolita.”

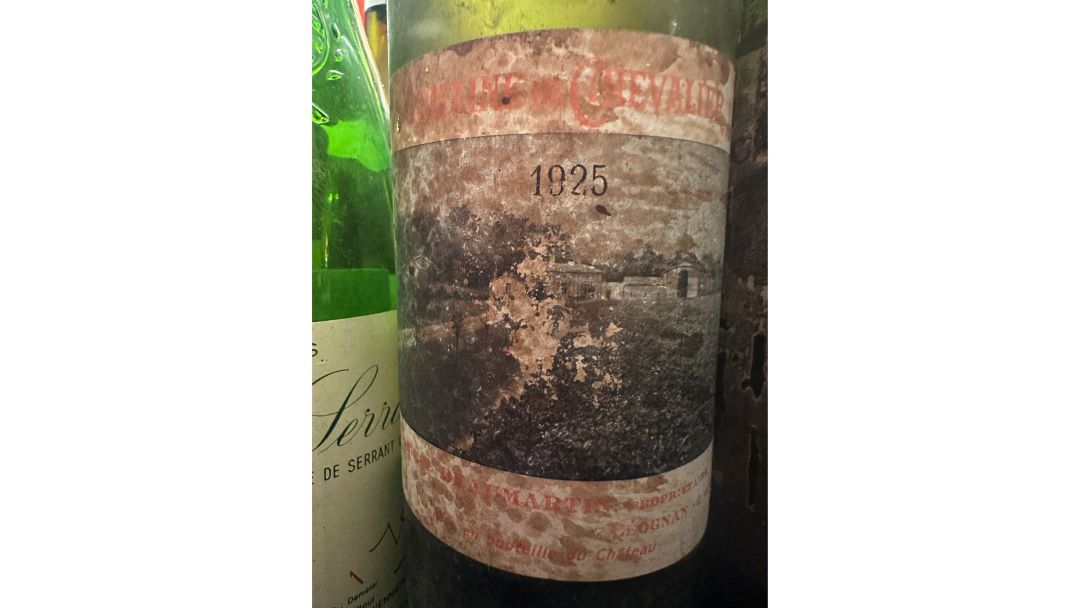

The

cavalcade of bottles ending in “five” lined up at Domaine de Chevalier, spanning

170 years.

Whilst Poe was racking his brain thinking of words that rhyme with raven (haven, maven, John Craven), grapes were being fermented for what eventually became a multi-vintage 1845 Bual Solera inside Cossart Gordon’s lodge. Vintages were added to that base wine, though which exact years are lost in the sands of time. Now, what are the odds that two invitees would bring the same Madeira? Sure enough, we had not one but two bottles, one stencilled, the other labelled. Of course, it is always a privilege to drink a time-defying Madeira, and both bottles had stood the test of time, one slightly more oxidized in style than the other, yet both with an inner core of sweetness.

1865 – “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland” – Lewis Carroll

Rowing up the Isis River with a friend and his three daughters, Oxford don Lewis Carroll ad-libbed a story about a girl called Alice who lived in the undergrowth. Three years later, in 1865, the most famous Victorian nonsensical novel hit the bookstores, its pages filled with white rabbits, Cheshire cats and the Madhatter’s tea party, a precursor to today’s wine dinners. “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland” has never been out of print since. I read it as a child. I found its surrealism unsettling and returned to the safe haven of Enid Blyton. At least the Famous Five did not play croquet with flamingos.

A tiny

handful of Bordeaux 1865s already exists in the Vinous database. This is a

legendary pre-phylloxera vintage on the Gironde, a favourite tipple of Michael

Broadbent. The vintage was equally revered in

Burgundy, hence my unearthing a single note from the epic La Romanée

vertical a decade ago, this one bottled by Bouchard Père & Fils.

1915 – “The Metamorphosis” – Franz Kafka

It must be a bit of downer to wake up and discover that you have transformed into a giant insect or monstrous vermin, however you interpret Kafka’s novella published in 1915. Imagine going to primeur tastings. It would be awkward. Like much of Kafka’s work, “The Metamorphosis” is not suitable as a child’s bedtime story, not unless you want to give them nightmares for life. Little did he know that he would inspire the title of my selected book for 2015.

Nineteen

fifteen is unusual insofar that it is renowned in Burgundy but an annus

horribilis in Bordeaux. Here, I’ve included a historical note for one of

the greatest Pinot Noirs that has ever passed my lips, however, the real star

of this article is a spellbinding bottle of 1915 Cheval Blanc that graced

the “Five” dinner at Domaine de Chevalier. After 110 years, this Saint-Émilion

was so vivid and refined, a humbling experience that elicited gasps of

incredulity. Consider that, aside from bloodshed in the trenches, at this time,

Cheval Blanc enjoyed a fraction of today’s renown, Saint-Émilion’s wines dismissed

as little more than early-drinking Merlot. Who would have thought that the

Château’s wines would be delivering sensory pleasure after a century? I have

drunk better vintages of Cheval Blanc, such as the 1934, 1948 and 1964, though

none have moved me as much as this warhorse.

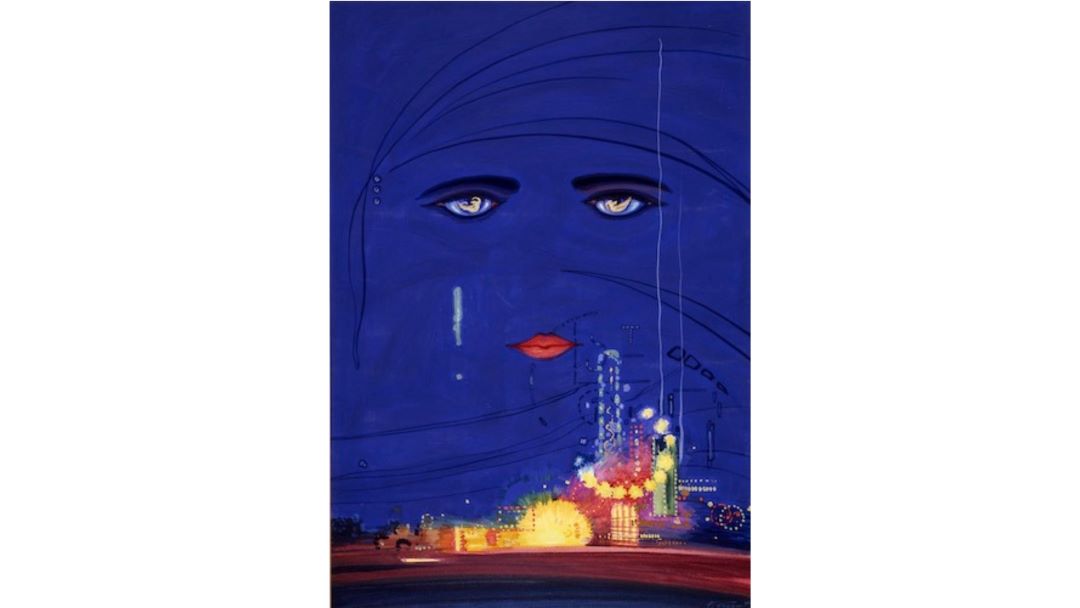

1925 – “The Great Gatsby” – F. Scott Fitzgerald

The story of a mysterious millionaire on Long Island was published in April 1925, replete with its striking “celestial eyes” dust jacket designed by Francis Cugat. Sales were sluggish after critics declared it a lesser work, and Fitzgerald died in 1940 convinced that “The Great Gatsby” was a failure. Popularity came posthumously when the novel was given away free to American soldiers serving during the Second World War. Ensuing scholarly reappraisal led to Gatsby becoming a standard school text. I remember studying it for my English O-level exams. It is the closest I have come to liking jazz.

Nineteen

twenty-five is the weak card in a fecund decade for Bordeaux vintages, an

inclement season that resulted in a late harvest and anaemic, low-alcohol wines.

It was a small crop, which is why 1925s are much less common nowadays than

coeval vintages like 1928. I had never encountered

a red until the Vieux Château Certan vertical last June, but Olivier Bernard

served a 1925 Domaine de Chevalier blind that, in no small part

due to impeccable provenance, was threadbare yet offered remnants of sensory pleasure

after a century.

1935 – “Death In the Clouds” – Agatha Christie

Most Sundays, I cycle up to Newlands Corner for a café latte with oat milk and admire the vista across the North Downs. Passers-by might spot flowers tied around a tree. This is where, at the height of her fame, the creator of Hercule Poirot and Miss Marple vanished like a character in one of her murder mysteries. Christie’s disappearance led to a nationwide hunt, and no less than Sir Arthur Conan Doyle took a break from writing Sherlock to consult a medium and divine her whereabouts. Christie reappeared 11 days later in a “fugue state” caused by depression after the discovery of her husband’s adultery.

“Death In the Clouds” is one of Christie’s “closed circle” novels insofar that the suspect must be one of the known characters, in this case, aboard a cross-Channel flight. That is much more romantic than basing it on the Eurotunnel train in a carriage full of bawling kids wanting to know when they are going to see the Eiffel Tower.

I add

three clarets and one Port to my gaggle of notes from 1935s, a year when the

world was amid the Great Depression, the Nazis ascendant in Germany. The first

dry white poured blind at the “five” dinner at Domaine de Chevalier was a fabled

wine I had heard about though never tasted. After floundering with guesses at a

20-year-old Loire, it turned out to be the 1935 Vin Blanc de Lafite. Purportedly,

this dry white was produced at the First Growth

until the 1960 vintage for private consumption, though inevitably a few bottles

leaked out. I do not know the blend, though it tasted like a Sémillon/Sauvignon,

perhaps more of the latter, like Pavillon Blanc? It

was remarkable in terms of freshness and complexity, not least its captivating

texture. The others include a slightly timeworn 1935 Malartic-Lagravière

Blanc at the Académie du Vin soirée, and a note I unearthed for the 1935 Domaine

de Chevalier poured at the same event a decade earlier that had gone AWOL.

Finally, a delicious 1935 Colheita Vintage Port from Niepoort

that carried its “boatload” of VA off in style, revealing a gorgeous caressing

finish that, to be honest, I preferred to the 1845 Madeiras.

1945 – “Brideshead Revisited” – Evelyn Waugh

“It is

a little shy wine like a gazelle.”

“Like a leprechaun.”

“Like flute by still water.”

“Like the last unicorn.”

Four descriptions of wine that you will certainly not find on Vinous, but you will find in Waugh’s famous 1945 novel about the landed gentry and teddy bears. Waugh authored the novel after a minor parachute accident while living on a diet of soybeans. He claimed this drove him to include the gluttonous references to food and wine that he later unnecessarily rued. These flowery descriptors are lifted from the scene when Charles Ryder and Sebastian Flyte raid the family cellar at their ancestral mansion. Nowadays, they would be arguing over points or whether it has Brettanomyces.

I must

have been saintly in my previous life to have

tasted most of the major Bordeaux 1945s over my career. Another six were added to the rollcall of wines that were beatified

by dint of birth in this année de victoire. One that really caught my

attention was the 1945 La Croix de Gay. I have found recent vintages not

coming up to muster, which I take no pleasure in, especially with cherished memories

of a vertical during research for my Pomerol tome that revealed the quality of

these wines in the postwar years. That vertical had started with the

magnificent 1947. This 1945 was in the same class, a jewel that glistens

brightly after eight decades. As expected, all the others performed remarkably

well, including a magnum of 1945 Domaine de Chevalier offered by Olivier

Bernard at the Académie du Vin black-tie dinner, even if, like some ‘45s,

passing time has abraded some gloss. When Bernard banged the gong to announce

that guests could fill their empty glasses, there was an inevitable stampede

for this magnum, incidentally one of only two that remained in the cellar. The 1945

Guiraudwas outclassed by the superlative ’55,

though the two divided opinion around the table. In a generous mood, I added a

long-lost note for the 1945 Château de Fargues, opened many years ago at

St. John restaurant. This wine remains significant for being my Sauternes

epiphany and coinciding with the precise moment when my first article on the

nascent Wine-Journal went viral. Sauternes-lovers might be unaware that,

though this 14th-century château connotes a deep sense of history, paradoxically,

vines were only planted in the 1930s, thus, de

Fargues debuted with the 1942.

1955 – “The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King” – J.R.R. Tolkein

Tolkien is synonymous with “The Lord of the Rings, The Return of the King,” the final installment of the trilogy. Tolkien was a fascinating man. Having lost his parents at a young age, the teenage Tolkien invented a fantasy language called Nevbosh, later fought in the Battle of the Somme, became a professor of Anglo-Saxon history at Oxford University, and delivered a seminal lecture on the Old English epic poem “Beowulf.” The first part of “The Lord of the Rings” was published in 1948, ten years after Tolkien’s first sketches of what became Middle Earth. Reading the trilogy was a rite of passage for any teenager. Nowadays, we just sit through Peter Jackson’s films. I don’t know which takes longer.

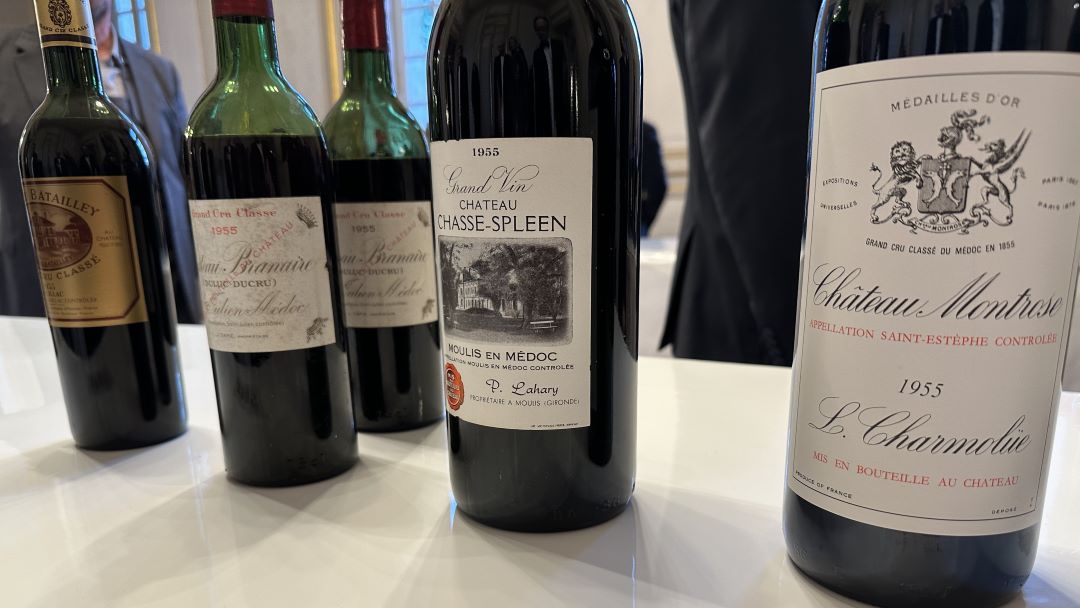

It

was a privilege to taste wines from the 1955 vintage, especially in large

formats direct from châteaux’s cellars.

Nineteen fifty-five is a vintage that has had a place in my heart ever since a Lynch Bages dazzled at a bacchanal many moons ago. It is a vintage that I eagerly look forward to drinking, though in recent years they have become thin on the ground. Nevertheless, I added another dozen-or-so Bordeaux wines here. Take away a decrepit 1955 Haut-Bailly that tantalised what a sound bottle could deliver, plus a 1955 Gazin and Corbin Michotte that were simply long in tooth, the rest have stood the test of time. They rarely hit the celestial heights of the ‘45s, yet the ‘55s have flourished in their dotage. The best were a sublime 1955 Branaire-Ducru and the redoubtable 1955 Montrose from magnum. The great virtue of this vintage is consistency throughout the Bordeaux hierarchy—the 1955 Trottevieille, Batailley and Poujeaux each tickle the tastebuds as they enter their eighth decade.

1965 – “The Man with the Golden Gun” – Ian Fleming

The James Bond film franchise had already made 007 a cultural icon by the time “The Man with the Golden Gun” hit bookshelves in April 1965. Fleming passed away eight months earlier. Ailing health meant that he was denied his usual practice of enriching the prose in its second draft and consequently, despite being another bestseller, it received lukewarm reviews. The film version starred Sir Christopher Lee as Bond’s adversary, the brilliantly named “Francisco Scaramanga.” Like all Bond baddies, Fleming named him after a real-life person, in this case, a fellow student at Eton College. Lee went on to star in Jackson’s “The Lord of the Rings” as another baddie, this time with a long white beard and supernatural powers, the only cast member who had actually once met Tolkien when he joined Lee’s group of friends at an Oxford pub. Perhaps, he wanted to practice his Nevbosh? If you like to connect the dots, Lee was Fleming’s step-cousin.

I crossed my fingers and toes that somebody would dare pour a wine from one of the most derided vintages of all time. One château did, though readers will find that in a separate article on Yquem. Predicting no-shows, I threw a curveball at Domaine de Chevalier and procured a 1965 Private Bin 721 from McWilliams, since Australia was one of the only countries to enjoy a decent growing season in 1965. True to form, this bottle delivered menthol-tinged perfume upon opening and remained quite lush. My only regret is that, though I advocate decanting mature bottles, in this case, the wine lost a little chutzpah by the time it was confusing guests around the table. I have also added two more notes from the archives apropos 1965, another from Australia and one from Spain, for those turning 60 this year.

1975 – “Il Sistema Periodico [The Periodic Table]” – Primo Levi

Like many, whilst I have forgotten most of the useless information crammed into my cerebral membrane at school, the two pieces of information indelibly printed are the formation of ox-bow lakes and the Periodic Table of Elements. “Il Sistema Periodico” is not a scientific textbook. It is Levi’s autobiography as an Italo-Jewish scientist in Mussolini’s Italy, including his arrest and internment at Auschwitz. The book begins with Levi’s childhood (argon) and finishes with carbon, though the most thought-provoking chapter is vanadium. By chance, Levi engages in business correspondence with a man who, as it transpires, was a supervisor at the Auschwitz laboratory and carries on as if to say, let bygones be bygones. The book is a clever mélange of fiction and nonfiction, chemical reactions as metaphors for life.

To my surprise, fewer bottles from this vintage were opened. Most châteaux preferred to open the seductive 1985s, or something older. Seventy-fives can be curmudgeonly on the Left Bank. A few reds did see the lights of day, though none that sent pulses racing. I would dearly love to retaste the 1975 La Mission Haut-Brion that has “evaded capture” for many years. By far the most astonishing was a 1975 Domaine de Chevalier Blanc that seemed preserved in aspic, remarkably pale and youthful to the extent that its retarded evolution bordered on shortcoming. Interestingly, you could argue the same for the 1975 Dom Pérignon P3. Juxtaposed against the original release and 1975 Oenothèque cuvées to commence Jordi’s birthday bash, some felt that the P3 shortchanged drinkers in refusing to offer secondary characteristics that are surely the reward for patience. Pomerol has always been the best Bordeaux appellation in 1975. I have enjoyed several bottles of the 1975 Petrus over the years, but this was the first time in magnum, a sublime Pomerol that oozes class and shows few signs of wear and tear, unlike a rather ragged 1975 Montrachet from Domaine de la Romanée-Conti, now too oxidative for my liking. Also, I must mention a splendid 1975 Château de Fargues at the Académie du Vin dinner that pipped the 1975 Rieussec.

1985 – “The Handmaid’s Tale” – Margaret Atwood

The degree to which the Canadian Margaret Atwood’s novel has become reality depends upon your political persuasion—not for debate here. However, one cannot dispute how it prefigures equality rights and #MeToo. Of course, the twist is that Atwood’s dystopian tale was based on historical fact. It is banned in several U.S. states and was removed from dozens of libraries, not under the 47th President, but the 46th. Both are male.

To the

best of my knowledge, I have never met anyone who dislikes the 1985 Bordeaux

vintage. More than 1986, more than even 1982 or 1989, the ‘85s are predestined

to seduce. A core of these tasting notes derives from a private dinner

organised at Noble Rot in London that featured four First Growths. I have

always adored the 1985 Château Margaux, the late Paul Pontallier

building on the success of his maiden 1983—sublime to this day. Also, the 1985

Haut-Brion is drinking gloriously, and it is a shame that our bottle of Haut-Brion

Blanc was slightly compromised, because previous showings have been sensational. At that

dinner, an ex-château bottle of 1985 La Conseillante stole the show with

its melted tannins and shimmering core of red fruit that is quintessential

Pomerol. Staying in that appellation, the 1985 Lafleur is sensational,

the first under Jacques and Sylvie Guinaudeau. Even after 40 years, it might benefit from further bottle age. There is a lot to

love about 1985 and, given market prices vis-à-vis en primeur, they look like extremely

attractive buys. Then again, so do many vintages.

1995 – “High Fidelity” – Nick Hornby

Did Hornby

base Rob Fleming on yours truly? The protagonist spends every waking hour

poring over his vinyl records and an unhealthy amount of time crate-digging in

manky old shops. Did he also have a penchant for old claret? The story is

really about Fleming working out his identity by reconnecting with old flames.

Nowadays, that would take just a few clicks of a mouse, but when “High Fidelity”

shot to the top of the bestseller lists, the internet was all dial-up modems

and AltaVista. The book sold over one million copies and inspired the

successful movie of the same name five years later. For the record, my vinyl

records are meticulously ordered alphabetically,

and I do occasionally ponder what happened to former paramours. No doubt

reading this and thinking “lucky escape.”

I would like to revisit this vintage more often and rue that more châteaux declined to show it, preferring their 2005s. Still, what I did manage to retaste proved that there were grounds for 1995’s rapturous reception following four lacklustre vintages and stumbling primeur campaigns. Time has taken a bit of shine off 1995, usurped by 1996, 2000 and 2005. One of the best and well worth seeking out if you are on a budget is the 1995 Phélan Ségur, opened on my first day during primeur, not to mention the excellent 1995 Grand-Puy-Lacoste. In fact, the best wine I tasted was not from Bordeaux at all, but California, the magnum of 1995 Madrona Ranch from Abreu.

2005 – “Kafka On the Shore” – Haruki Murakami

Murakami

is my favourite author, also that of Guillaume d’Angerville. “Kafka on the

Shore” was published in English in January 2005. Its

pages are littered with the usual tropes: talking

cats, music (Beethoven) and a young man living a humdrum life in the magical

reality world. No, no, no…it’s not about wine critics. Its publishers invited

readers to submit questions about the novel, and of

the 8,000 received, Murakami answered around 1,200. I bet Kafka did not do that

after “The Metamorphosis.”

Time slips like sand through my fingers knowing that two decades have passed since the 2005 vintage. Remember the hullabaloo surrounding its release? It was the first vintage propelled by Internet hype, though Parker’s scores were not as high as you might presume. I often return to this vintage in verticals, and a cluster of notes here derive from a 2005-themed dinner in London. Many châteaux opened this vintage during visits, though I cannot overemphasise the importance of decanting. I am grateful that estates opened these bottles, but frankly, far too many popped and poured, denying the wines the three to four hours of aeration they require.

One of the finest wines of the vintage, the 2005 Château Margaux was made by the late Paul Pontallier.

The 2005s tasted unapologetically “old school,” not least in terms of firm, almost obdurate tannins that manifest different wines than those of recent vintages with silky textures and lace-like tannins. To the uninitiated, the 2005s must seem brutish. It is a vintage that might put neophytes off claret for life. Readers will find around 50 Bordeaux 2005s that left more questions than answers. The 2005s often brought to mind vintages such as 1975 or 1986 insofar as they are dominated by tannins and fruit plays second fiddle, though 2005 is superior to both. These wines are often quite ferrous in style, the word “burly” appearing several times, yet they do possess substance and horsepower, akin to a team of rugby players rather than the ballet dancers to which palates have become accustomed. Personally, I would give the 2005s more time, but if you do want to enjoy them now, decant, decant, decant.

2015 – “The Story of the Lost Child” – Elena Ferrante

The final part of Elena Ferrante’s four-part “Neopolitan” novels completes the life stories of the frenemies, Lenù and Lina. Readers had been captivated by 2011’s acclaimed debut, “My Brilliant Friend,” which the New York Times declared the best book of the 21st century (“Wolf Hall”? “Overstory”? My personal pick? “My Absolute Darling” by Gabriel Tallent). The series traces the girls’ interweaving lives as they grow up in a working-class, politically charged neighbourhood of Naples, Italy and concludes with their somewhat embittered lives as older women. Ferrante is a pseudonym. Despite interviews, little is known about her real identity, the author arguing that a book has no need for an author if the story is good enough.

The

lineup of Burgundy white 2015s and 2005s was a fascinating look back at two

well-regarded vintages.

The 2015s are better served in my standalone retrospective article from earlier this month. Since this piece is a celebration of numerical vintages, this section shifts towards Burgundy 2015s courtesy of bottles tasted at various domaines in autumn last year, augmented by a handful of whites at a Southwold dinner in January. Indeed, I was mightily impressed by the performance of these Chardonnays, taken by their slow evolution and vitality. Perhaps overlooked by cognoscenti, these are well worth seeking out, especially the likes of Jean-Marie Guffens in the Mâconnais (despite some overinflated secondary market prices), Domaine des Comtes-Lafon, Arnaud Ente and Colin-Deleger. One alternative is a superb Oregon white, the 2015 Chardonnay Old Vines from Eyrie Vineyards, poured in January—as good as any Burgundy you will find that year.

Final Thoughts

I hope you have enjoyed this journey through time, signposted by books. The written word has entertained and educated since Gutenberg invented the printing press. Today, life hurtles at an unprecedented pace. Too often, we—myself included—forget to hit pause, pick up a book and whisk ourselves into an author’s world. The book is a brake made of ink and paper. To read words on a screen as you are doing now is one thing. To hold them in your hands is entirely another.

Reflecting upon my choices, I pondered whether literature has changed between 1845 and 2015. Not really. Certainly not like music that is predesigned to be mutable, constantly splintering into today’s kaleidoscope of sub-genres. Spare from the physical dimensions of a book that are virtually unchanged, there is the constant of language and grammatical rules. You might compare that to wine, where instead, a winemaker is constricted by vine, terroir, vinification and expectations of how it will all taste. Like literature, winemaking rules can be stretched, bent, >or perhaps (apropos natural wine) broken! But there is one uncontrollable variable: time. Whereas the written word is fixed as soon as any book rolls of the press, time is wine’s invisible sculptor that imbues secondary aromas and flavours to manifest an alternative realm of sensory pleasure. No other wine region does that with Bordeaux’s aplomb.

Time gifts us the profound act of consuming history.

Wine and words.

Perfect for nourishing the soul.

© 2025, Vinous. No portion of this article may be copied, shared or re-distributed without prior consent from Vinous. Doing so is not only a violation of our copyright, but also threatens the survival of independent wine criticism.You Might Also Enjoy

A Century of...Fours, Neal Martin, June 2024

A Century of Bordeaux: The Threes, Neal Martin, August 2023

A Century of Bordeaux: The Twos, Neal Martin, September 2022

A Century of Bordeaux: The Nines, Neal Martin, September 2019

Show all the wines (sorted by score)

- Abreu

- Angélus

- Barde-Haut

- Batailley

- Beychevelle

- Bodegas Vega Sicilia

- Bouchard Père & Fils

- Branaire-Ducru

- Calon Ségur

- Canon

- Cayuse

- Chasse-Spleen

- Château Margaux

- Cheval Blanc

- Clerc Milon

- Climens

- Clos du Marquis

- Clos Lafaurie-Peyraguey

- Clos l'Eglise

- Clos Rougeard

- Corbin Michotte

- Cos d'Estournel

- Cossart Gordon

- Coutet

- d'Armailhac

- de Fargues

- De Malle

- De Myrat

- de Rayne-Vigneau

- Doisy-Daëne

- Doisy-Védrines

- Domaine Amiot-Servelle

- Domaine Armand Rousseau

- Domaine Arnaud Ente

- Domaine Bernard & Thierry Glantenay

- Domaine Bitouzet-Prieur

- Domaine Bruno Clair

- Domaine Chandon des Briailles

- Domaine Claude Dugat

- Domaine Clos de Tart

- Domaine Colin-Deleger

- Domaine Comte Georges de Vogüé

- Domaine de Chevalier

- Domaine de la Romanée-Conti

- Domaine de Montille

- Domaine Denis Mortet

- Domaine des Comtes-Lafon

- Domaine des Croix

- Domaine d'Eugénie

- Domaine Dubreuil-Fontaine

- Domaine du Comte Liger-Bélair

- Domaine du Comte Liger-Belair (Morin)

- Domaine Faiveley

- Domaine Felettig

- Domaine Follin-Arbelet

- Domaine Fourrier

- Domaine François Buffet

- Domaine Gérard Mugneret

- Domaine Ghislaine-Barthod

- Domaine Guffens-Heynen

- Domaine Guy Roulot

- Domaine Henri Clerc

- Domaine Henri Magnien

- Domaine Jacques Prieur

- Domaine Jean-Claude Bachelet

- Domaine Jean-Claude Ramonet

- Domaine Jean et Jean-Louis Trapet

- Domaine Jean-François Coche-Dury

- Domaine Jean Grivot

- Domaine Jean Tardy

- Domaine Jérôme Galeyrand

- Domaine J.L. Chave

- Domaine Leflaive

- Domaine Macle

- Domaine Marquis d’Angerville

- Domaine Méo-Camuzet

- Domaine Michel Gros

- Domaine Michel Lafarge

- Domaine Michel Mallard

- Domaine Morey-Coffinet

- Domaine Mugneret-Gibourg

- Domaine Nicolas Faure

- Domaine Perrot-Minot

- Domaine Pierrick Bouley

- Domaine Sylvie Esmonin

- Domaine Vincent Dauvissat

- Dom Pérignon

- Felton Road

- Filhot

- Gazin

- Grand-Puy-Lacoste

- Gruaud Larose

- Guiraud

- Haut-Bages Libéral

- Haut-Bages-Libéral

- Haut-Bailly

- Haut-Brion

- La Conseillante

- La Coulée de Serrant/Nicolas Joly

- La Croix de Gay

- La Dominique

- Lafaurie-Peyraguey

- Lafite-Rothschild

- Lafleur

- La Mission Haut-Brion

- Lamothe- Guignard

- Langoa Barton

- Larcis Ducasse

- Latour

- La Tour Blanche

- Latour-Martillac

- Laville Haut-Brion

- La Violette

- Léoville Barton

- Léoville Las Cases

- Léoville Poyferré

- L'Evangile

- Lynch Bages

- Margaux

- McWilliams

- Montrose

- Mouton Rothschild

- Nairac

- Nénin

- Niepoort

- Ormes de Pez

- Palmer

- Penfolds

- Petrus

- Phélan Ségur

- Pichon Baron

- Pichon-Longueville Comtesse de Lalande

- Poesia

- Potensac

- Poujeaux

- Rabaud-Promis

- Rauzan-Ségla

- Rieussec

- Roc de Cambes

- Romer du Hayot

- Sigalas-Rabaud

- Siran

- Suduiraut

- Talbot

- Tertre-Rôteboeuf

- The Eyrie Vineyards

- Trotanoy

- Trotte Vieille

- Vincent Girardin

- Yquem