Browse using the new Vinous website now. Launch →

Printed by, and for the sole use of . All rights reserved © 2015 Vinous Media

The Marital Margaux: d’Issan 1945-2015

BY NEAL MARTIN | JULY 24, 2018

Who doesn’t love a good wedding? Mothers-in-law locking horns over floral arrangements and whether or not “drunk” Uncle Raymond should be on the wedding list. The stag party that ended in a police caution. The hen party that witnessed Jägerbomb-fuelled banshees running amok on a rain swept esplanade brandishing giant inflatable willies. Blushing bride walking down the aisle whilst the groom fidgets nervously at the altar; bride’s father dabbing away a tear at the thought of his beloved marrying this buffoon. The solemnity of exchanged vows, you stifling giggles having spotted three-year old Timothy picking his nose (flush-faced Uncle Raymond doing likewise in the pew behind.) The pomp of the wedding march. The confetti still stuck in your hair days later. Speeches: too long, too dull, too unfunny or so shocking that Aunty Vera never looks you straight in the eye again. The leaning tower of wedding-cake. Tacky disco! Dance-floor swarming with dads demonstrating their moves in front of impressionable children wondering why these men are making synchronized pelvic thrusts to Taylor Swift (with Taylor Swift in their minds.) Uncle Raymond passed out under the buffet surrounded by a detritus of half-eaten chicken wings. The unspoken hope that the newly-weds’ life savings squandered on their honeymoon means they are too broke to divorce twelve months later.

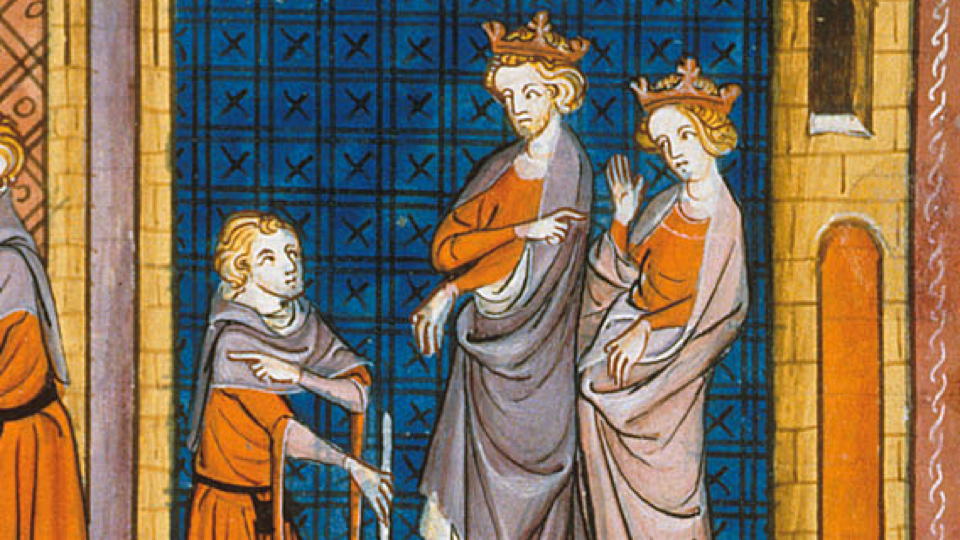

Henry, Duke of Normandy and Eleanor, Duchess of Aquitaine, depicted above, in the 14th century

This writer was never invited to the nuptials of Henry, Duke of Normandy and Eleanor, Duchess of Aquitaine, as depicted above, in the 14th century. Inconveniently, I was born a few centuries too late. Even if I were, I doubt a common rake like myself would have been invited to a royal wedding that united England and France with profound ramifications for Bordeaux and Europe, like a reverse-Brexit, but with less bloodshed. However, I like to think that their ceremony back on 18 May, 1152 was not too dissimilar to the one described. For certain I would have approved of the wine served at their reception before the lute quartet struck up “Come On Eileen”. That is because instead of pouring some fermented 16.5% “paint-stripper” discounted at the local cash ‘n carry, guests would have toasted the nuptials to a wine known as La Motte Cantenac.

You know it as Château d’Issan.

Amazingly, some 866 years later, visitors can still tour the château and imbibe the wine that Henry and Eleanor purportedly drank on their wedding day. D’Issan celebrates the occasion every three years and last May, on the eve of another royal wedding uniting England and the United States, I attended a dinner at the Palace of Westminster to raise a toast to Henry and Eleanor, accompanied by some large format bottles of d’Issan. But this article really focuses upon a comprehensive vertical that I undertook with Emmanuel Cruse a few weeks earlier that spanned the entire postwar period. First, let’s colour in the châteaux’s history, because it goes back a very long way.

Château d’Issan, with its drawbridge and moat, is one of the most evocative châteaux in Bordeaux

History

If you want to visit a fully functioning castle replete with drawbridge and moat, alas without any crocodiles (as far as I know) then head to Château d’Issan in Margaux. Unlike other châteaux, the facade of d’Issan does not gaze upon passers-by driving up the D2 artery. Instead, d’Issan nestles out of sight behind its ancient perimeter wall so that many visitors ignorantly zoom past one of the most aesthetically pleasing properties on the Left Bank. The interior reeks of history from its antique furniture to the heavy drapes, silver candelabra, framed sepia-tinged photographs of the Cruse family upon mahogany tables. The walls of the main stairwell are decorated with coats of arms, an array of animal skulls and a veritable herd of stuffed deers’ heads that together imbue d’Issan a gothic atmosphere. I would not believe you if you told me d’Issan is not haunted.

Château d’Issan is one of the most ancient estates in Bordeaux, and traces its history all the way back to the 12th century. Hosting the nuptials of the future King Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine in 1152 meant that d’Issan entered the lucrative wedding venue market early. At that time this maison noble was known as “La Mothe-Cantenac” and later “Théobon Manor”. It passed through the hands of several families including the all-powerful Ségurs before five generations of the Essenault family commenced their tenure in 1575, a period when heiress Marguerite de Lelanne married a Bordeaux parliamentarian, Pierre d’Issenhault. Renaming the estate “Issan”, they tore down the manor house and constructed the present château and chiseled their motto above the main arched entrance: “Regum Mensis Arisque Deorum” - “For the table of kings and the altars of the gods.” In 1644 the vineyard was surrounded by a stone wall to create one of the Left Bank’s few genuine clos. [There are three others in Bordeaux, one in each appellation. Answers at the bottom of this article.] The Issenault family’s proprietorship came to an end in 1760 when the property was sold to the Castelnaus and subsequently divided between Castelnau and the Foix de Candale family, the former owning the land and the latter the château building. The Candales eponymously renamed the estate, ergo for a period of time maps show it as “Château de Candale”, the title Thomas Jefferson refers to in his list of Third Growths in a letter written in 1787.

The vineyard was split by the two families and reunited upon Justin Duluc’s acquisition in 1825. In 1866 Gustave Roy took the keys to the property and as incumbent proprietor of Brane-Cantenac, he applied the same tenets of quality-focused winemaking, installing surely the first gravity-fed cellars in the region whilst tackling the scourge of phylloxera in the vineyard. Unfortunately after the First World War the estate fell into disrepair, like so many in Bordeaux suffering from a market malaise, lack of investment and a run of poor vintages, not to mention war itself. Ownership had passed to the Grange family and by 1931 production withered to just 70 tonneaux. The tumult of the Second World War brought d’Issan to the brink of extinction so that in 1945 a pitiful 2 tonneaux was cropped from just three hectares of productive vines. Would d’Issan be yet another casualty of the war? Almost. In April that year, Emmanuel Cruse, grandfather of the namesake current co-owner, bought d’Issan for a purported bargain price of five million francs and a new era began.

“In fact after the Second World War my grandmother put pressure on her husband to have her own private château,” Emmanuel explains. “This is because Pontet Canet, Rauzan-Ségla and the others belonged to the wine merchant company, Cruse et Fils Frères. After different attempts [to purchase a property] were made on the Right Bank, they finally decided to buy d’Issan, which was quite abandoned at the time. Nevertheless, it had been made a classified Third Growth in 1855 and it was very close to Rauzan. Since they bought d’Issan just after the war they had to rebuild the vat house and cellar, so vintages between 1945 and 1950 were vinified at Rauzan-Ségla.”

The restoration of such a large property is not something that happens overnight, although one can argue that its sister property, Château Pédesclaux has done exactly that in a short space of time. I ask Emmanuel when he felt that investments in d’Issan began to improve the quality of the wine.

“As far as I am concerned I started to work with my father in 1994 and officially began as general manager in 1998. The major investments started in 1995 with a complete new drainage system in the vineyard, the creation of Blason d’Issan as an experiment in 1994 and officially in 1995. This is a selection based on the age of the vineyard. Then in 1999 a new barrel cellar began construction and a complete new vat-house in 2002. This includes 37 temperature-controlled stainless steel vats ranging in size from 70- to 200-hectolitres for each parcel. In 2003 we introduced a new technical zone and a complete new system for the harvest in 2014.”

The long history of Château d’Issan turned another corner in 2013 when the descendants of Roland Cruse, Lionel’s brother, sold their 50% stake to Jacky Lorenzetti, who had made their fortune through the property group Foncia, and were already owners of Lilian-Ladouys and Pédescalux in Saint-Estèphe and Pauillac respectively. Emmanuel Cruse thus became co-owner and Managing Director of all three estates, as well as continuing his role as Grand Maître de la Commanderie de Bontemps, which amongst other duties involves a lot of dressing up in fancy cloaks and asking me if I can DJ at Fête de la Fleur (never say jamais, Emmanuel.)

The walls of the main stairwell decorated with stuffed deers’ heads that together imbue d’Issan a gothic atmosphere

Vineyard and Vinification

I asked Emmanuel Cruse to give more detail about the vineyard and vinification.

“Our Margaux vineyard is 44.8 hectares: 30 hectares in our “clos” inside the wall and 14.8 hectares in Arsac, between Giscours and Monbrison. Part of the wall fell down so we had to repair it and that was finished in January 2016. [There are also 5 hectares in Haut-Médoc and 10 hectares closest to the estuary classed as Bordeaux Supérieur.] The soil is composed of clay, gravels, and gravel with sand in the commune of Arsac. Grape varieties comprise 65% Cabernet Sauvignon and 35% Merlot. Pruning is in the classical Médoc style and the rootstocks are 101/14, 3309 C, and Riparia. Eric Pellon has been our technical manager since 1993. The harvest is entirely hand-picked by two teams, one a group of locals, and the second a crew of Danish students, approximately 120 pickers in all. With respect to the vinification process, from the reception of the fruit, we undertake a first selection on a vibrating sorting table, then the de-stemmer, then another selection on the berries on a second vibrating sorting table. The wine spends approximately one week in the vats for the alcoholic fermentation plus two additional weeks of maceration, and is then matured for 18 months in barrels using 50% to 55% new barrels for d’Issan and 35% for Blason d’Issan.”

I ask Emmanuel Cruse how he would describe the style of d’Issan.

“We definitely try to respect the authenticity of our terroir, with probably a better concentration and a better purity and precision and elegance on the nose,” he replies and with that, it is probably a good time to commence our discussion of the wines.

The Wines

This vertical is unique insofar that the estate possesses just a handful of ancient bottles. For example there are only six remaining bottles of the 1945. Therefore, tasting these vintages together is a privilege and hopefully provided as much insight for the team at d’Issan as it did for myself. On the other hand, my job is not to genuflect in front of rarity or age. My job is to describe each wine as I perceive it; assess its quality and then place it within the context of its peers.

The simple fact is that the finest bottles of d’Issan are not the oldest, nor the most reputed vintages. The finest bottles are the most recent. The truth is that World War Two ravaged the estate to such an extent that it required decades to fully recover. Brought to its knees by a lack of investment and care, production dangled by a thread and without a winery to actually make any wine, it is remarkable that the estate eked out a 1945 at all. The 1945 d’Issan does not rank amongst the great wines of that victorious vintage, many of which astonish to this day. After 73 years it is clutching onto its mortal coil by its fingernails, a Margaux that confers upon the taster historical significance rather than sensory satisfaction. To be honest, the ensuing vintages that proffered a rash of astonishing Clarets, witnessed wines from d’Issan that do not hold up to the greatest names (not dissimilar to Rauzan-Ségla in the same period.) The 1947 d’Issan is disappointing given the reputation of its birth-year and 1953 d’Issan, whilst easygoing and charming, feels as if it has lost much of its lustre. The 1955 d’Issan hints at recovery a whole decade after men put down their arms, albeit a little too “serious” for my liking. The commendable 1961 d’Issan suggests that recovery is imminent, even if that is no magnet for superlatives. Surely the estate would soon be firing on all cylinders, a long-term rehabilitation that would see it become one of the most respected Margaux crus by the 1980s.

That is not how the story unfolded. The 1966 d’Issan is an omen for things to come, two bottles opened and both suggesting that something went seriously awry during the vinification, perchance some bacterial infection? A period of malaise followed during which d’Issan became a Margaux also-ran. Few of the vintages from the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s matched my expectations, even taking into consideration that in this era of “old school” winemaking, d’Issan sort of “ambled” along and its ordinary wines only sullied its reputation. It is notable that Emmanuel Cruse himself felt that many bottles were not worth showing, hence no 1982, 1989 or 1990. Moulin d’Issan was introduced in 1988, a Bordeaux Supérieur from vines located just outside the Margaux appellation. The late Jacques Boissenot was appointed consultant in 1994. The following year saw the second label renamed Blason d’Issan, as well as a new drainage system installed in the clos whilst between 1996 and 2000 parcels were replanted at a higher density of 9,000 vines per hectare.

The 1999 d’Issan testifies that investments and greater selection began improving the wine, and frankly it surpasses every vintage back to the 1961. That is some achievement, especially considering 1999 was a mediocre growing season. It is not until this point that the post-war recovery really starts. Better late than never! Hereafter, the resurrection of d’Issan commences, made all the more possible by the new barrel cellar that Emmanuel Cruse mentioned earlier. The real turnaround is the 2005 d’Issan, a wine that attests to how the new winery immediately improved quality. Examining the figures, whereas up until the early 1990s the entire crop was dedicated to the Grand Vin, in 2005 it was just 67%, falling further in subsequent years to around 50% to 55%. Finally d’Issan could compete with its peers though, perhaps its non-participation in UGC events kept it under the radar. The 2008 d’Issan stands as one of the hidden gems of that vintage, the 2010 d’Issan one of its modern-day pinnacles even though it does require considerable cellaring. “It is the first d’Issan in the sense that it is the least technical vintage,” Emmanuel explains. I also draw attention to the over-performing 2012 d’Issan, which represents just 43% of the total production, and even the 2013 d’Issan is not half as bad as I bet you expected.

When I look back at this vertical, I perceive it as a very long recovery. It took decades for d’Issan to overcome the traumas of 1939 to 1945 and the estate lagged behind its peers in terms of investment. Quality has only caught up with modern-day Bordeaux over the last decade or so. Stylistically, I see some similarities between d’Issan and Brane-Cantenac, in the way if often captures a Pauillac-like graphite vein, with a little more structure than other Margaux. That inbuilt austerity needs to be counterbalanced by fineness of tannins, something that has only been addressed by Emmanuel Cruse and his team in recent years. Now d’Issan is a more polished Margaux, sleeker in style, certainly more approachable in its youth and yet full of breeding. “Now we are playing with more mature vines,” Emmanuel opines. “Today, we have more structure in the wine. We work for the next generation in terms of replanting. We are the lucky generation. In the future I think there will be global warming that will make better Cabernet Sauvignon and we may plant more Petit Verdot.”

I wonder if Henry and Eleanor appreciated the wine during their own nuptials? Did it turn out to be a marriage made in heaven? Pray tell, did they settle down in a semi-detached castle and rule their kingdoms in a state of unending marital bliss?

Well, on the plus side they sired eight children, three of which became kings, even if one of them led the Crusades that brought thousands of deaths. On the down side, there was in fact an “Uncle Raymond” and prior to marrying Henry, rumours of an incestuous relationship between them were rife, likewise an affair between Eleanor and Henry’s father, the Comte d’Anjou. Hmm...complicated. In fact, one medieval scholar observed: “She is more a whore than a queen.” Henry and Eleanor had a tumultuous relationship, with Henry a renowned philanderer who sired a number of illegitimate children. They became estranged and Eleanor relocated back to Bordeaux, where along with three of her sons, she connived a revolt against her ex-husband. Henry ordered her to be imprisoned as soon as she set her dainty foot back upon English soil in 1173. Despite that “minor” 16-year incarceration, Henry and Eleanor patched it up so that by the time of his death in 1189, his ex-missus was allowed to roam around under supervision. So it was not exactly plain sailing.

But hey, at least they drank well on their wedding day.

* The three other clos are in Calon-Ségur (Saint-Estèphe), Latour (Pauillac) and Clos du Marquis (Saint-Julien)

(My thanks to Emmanuel Cruse and his team for organizing this vertical tasting at the property, as well as the dinner at the Palace of Westminster.)

You Might Also Enjoy

Cellar Journal – Bordeaux to Start…, Neal Martin, July 2018

Looking Back To Go Forward: Lafite-Rothschild 1868 – 2015, Neal Martin, July 2018

In Excelsis: Château Latour 1887 – 2010, Neal Martin, July 2018

Bordeaux In Excelsis, Neal Martin, June 2018

Last Man Standing: Bel-Air Marquis d’Aligre, Neal Martin, May 2018

A Century of Bordeaux: The Eights, Neal Martin, May 2018

Purple Reign: La Conseillante 1966-2015, Neal Martin, May 2018

The F-Word: Bordeaux 2017, Neal Martin, April 2018