Browse using the new Vinous website now. Launch →

Printed by, and for the sole use of . All rights reserved © 2015 Vinous Media

Port Is For Life: Symington Vintage & Tawny Ports

BY NEAL MARTIN | DECEMBER 11, 2018

“Port is for life, not just for Christmas.” True, though I am sure sales figures would confirm that more bottles of port, in all its multifarious forms - Vintage, Ruby, Tawny, Single Quinta, Colheita, White or Crusted - are ceremoniously passed to the left over the festive period than at any other time of the year. So it would be remiss of me not to offer Vinous readers an early Christmas present in the shape of a port-themed article (and no, I have not got the receipt if you don’t like it.)

Paul Symington, discussing post-retirement plans following his last official tasting as chairman of Symington Family Estates

This article follows a tasting of Symington Family Estate’s Vintage and Tawny Ports, held within the medieval walls of the Tower of London. Outside, herds of excitable schoolchildren were shepherded into crypts to gawp at the Crown Jewels by a very Essex-sounding Henry VIII, while inside, port lovers gathered in the New Armouries Hall to see an equally excitable Paul Symington undertake his final official tasting as chairman before handing over to his 49-year-old cousin, Charles Symington. I am not being facetious or disparaging when I describe Paul Symington as “excitable” - quite the opposite. That is just the way he is. Cut from the same pinstriped cloth as Adrian Bridge at Taylor Fladgate or Christian Seely at Quinta do Noval, he is of good English stock, yet thoroughly European. Symington is voluble and animated, his Received Pronunciation interspersed with the odd expletive grenade. His untrammelled passion and almost boyish enthusiasm have been extremely important in reinvigorating Symington’s brands: Dow, Graham’s, Warre’s, Quinta da Vesuvio and, since 2010, Cockburn’s, not to mention their dry Douro white and reds. Charles Symington’s career has focused more on the hands-on winemaking side than Paul’s. Born in Portugal and growing up there until age eleven, Charles honed his craft in regions such as Rioja and South Africa before returning to the Douro. He is more reticent compared to his cousin, his conversation more measured, and perhaps not a raconteur like the outgoing (in both meanings of that word) chairman, but up to the task of leading Symington forward.

One aspect of the business that I did not know is that all family board members run their own estates and are obliged to sell the fruit to Symington Family Estate at the same price as contracted farmers. For this reason, on more than one occasion during the tasting, Paul Symington stressed the idea of the Symingtons not as shippers but as growers. Apart from the family’s own holdings, some 969 grape growers are contracted, 43% of them tending less than half a hectare, with much of the fruit destined for their commercial labels and Ruby Ports that are so financially important.

Paul Symington commenced the tasting with a candid assessment of the port industry and the challenges it faces. He cut to the chase by announcing, “We must adapt or die.” He remarked that the 43,000 hectares of vines in the Douro is larger than sherry production in Jerez, and much of it is located on mountainous terrain that necessitates costly picking by hand. That entails considerable labour, particularly during harvest. Oddly enough, many pickers now come from France, whilst Portuguese harvesters continue the tradition of migrating for seasonal work in Bordeaux, Languedoc-Roussillon and so forth. Thank goodness there is no Brexit on the horizon for those two countries.

Symington refuted the media portrayal of an industry in decline. “The good news is that port has managed to do something spectacular,” he enthused. “Last year 43% of sales was in the premium category. Since 2010, premium sales across all port houses increased by €29 million, and we believe that will continue. Around €21 million has been in the category of old Tawny Port. Furthermore, the last two declarations in 2011 and 2016 have been the most successful ever, both selling out by the end of July.” He also cited the secondary market as a barometer for success, pointing out that 2007 Vintage Ports are now double the price they were in 2013 and that their 2011 Dow is now three times its original value.

Symington continued by demonstrating how far the industry has progressed in the last 30 or 40 years, showing a silent black and white Ciné film shot in 1959 depicting rabelos, wooden boats laden with pipes of port being tossed by the rapids of the Douro River on their perilous journey to shipper’s lodges in Vila Nova de Gaia. It was the only means of transport, and this was not really that long ago. Not only has the infrastructure of the Douro radically changed, but there has also been progress in the vineyard in terms of trellising and reorganisation of vineyards - for example, replanting Tinta Franca close to the river facing eastwards has been found to favour that grape variety. “I think we are using better wines than ever,” Symington concluded, and given the quality of recent vintages, I concur.

Charles Symington joined the company in 1995. He recently persuaded the Symington board to invest in the development of a €500,000 machine that picks grapes efficiently, albeit more slowly, than conventional mechanical harvesters (not that they can be used given the rugged, steep terrain). Paul remarked that this new machine was undergoing trials, and to their chagrin, they found that it cannot pick bunches on the inside row of the terrace. But they are looking on the bright side, since many terraces in the Douro accommodate a single row and if a machine picks half the terrace, the harvest team can deal with the rest. That will be advantageous in growing seasons when the picking must be expedited or when labour is difficult to recruit, a constant though rarely mentioned challenge that Symington mentioned apropos of the 2016 vintage.

Ports Vintage and Tawny in all their array of colours, ready to be tasted

The tasting focused upon the Tawny Port category, though we commenced with Vintage Ports, including the recently released and quite outstanding 2016 Graham’s Vintage that showed exactly the same as it did earlier this year. The 1963 Graham’s is one that I had not previously tasted. Paul Symington described 1963 as the “Everest of ports,” a benchmark against which succeeding declarations are judged. On a personal level, he explained how 1963 was the first declaration since 1929 whereby the Symington family made any money, and quipped that it paid for his sister’s and his own schooling. So how was it? Well, the first bottle was corked and the second was decent enough, but did not achieve the ethereal heights of others that I expected. It came across thoroughly enjoyable yet a tad timeworn, suggesting that at 55 years of age, it may not have been born with the staying power of 1963s from other port houses. Indeed, in Michael Broadbent’s most recent note on the 1963 Graham’s, he wrote, “delicious but fading.” On this occasion I preferred the 1994 Graham’s Vintage. “You judge whether a vintage is truly great in its 20th year,” Symington opined. “There is nowhere to hide anymore and you can see whether it has made the grade.” The 1994 Graham’s has reached that mellow stage, moving into second aromas and flavours, quite spicy yet refined and persistent. It certainly suggests one of the greatest postwar Graham’s that I have tasted and comes highly recommended.

We then moved on to the Tawny Ports that are matured in Vila Nova de Gaia instead of the Vintage Ports up in the Douro Valley. Here there is less temperature variation plus a lower humidity level, which influences the rate of evaporation as reserves of Tawny Port mature. To give you an idea, Symington explained that around 35% of the Tawny Port evaporates over a 20-year period. This tends to concentrate the wine, rendering Graham’s and Dow’s Tawnies sweeter than their counterpart Vintage Ports. Symington is one of the only port houses with their own cooperage. In total they produce approximately 17,000 casks, including many barrels that have been used to mature red wine, since the Symingtons abhor the use of new wood. Most casks are around 80 to 100 years old and, in Paul’s opinion, will last another 80 or 100 years.

The tasting embraced both Graham’s and Dow’s Tawny Ports, and Paul Symington began with a reminder that, unlike Vintage Port, Tawny Port is designed to be drunk soon after release. The port house has already aged the Tawny for you, so there is no real upside to cellaring. For this reason, I have offered 5- to 10-year drinking windows to indicate that they will hold up, but to be honest, buy, open, drink and enjoy.

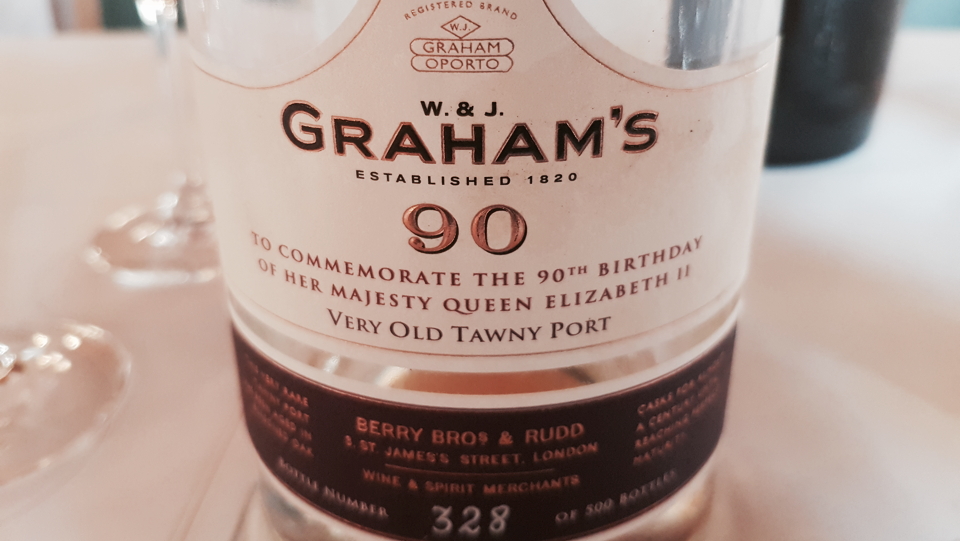

The 20-Year Old Tawny Port is a sweet spot in terms of price and quality, though I much prefer Dow’s with more concentration and presence. Of the older Single Vintage Tawny Ports, the 1994 showed very well. The reserves for this come from Quinta dos Malvedos, selected by Paul Symington, who was head winemaker at that time. Both the 1969 Cockburn’s Single Harvest Tawny Port and the 1972 Graham’s Single Harvest Tawny Port are impressive and quite spicy, particularly upon the aftertaste. The Cockburn’s has never been released – I hope that it will be in the future. I felt that the 1963 Graham’s Single Vintage Tawny lacked some vigour on the nose, though this was compensated by the complexity shown on the palate. We finished with Graham’s 90-Year Very Old Tawny, a blend of 1912, 1924 and 1935 reservas, limited to 500 bottles, made to celebrate the Queen’s 90th birthday. (I am unsure whether Her Majesty partook of a cheeky glass.) This is extremely fine: quite decadent and honeyed, surprisingly rich and vigorous, with a concentrated finish that belies its age. It sells for around $1,000 per bottle, so it is not cheap, but it is appropriately regal, and you could argue that it is not as expensive as the deluxe 19th-century releases that have become de rigueur for port houses in recent years.

That concluded the tasting. For completeness, I have supplemented these notes with one or two very old Graham’s and Quinta dos Malvedos ports to add to the Vinous database. Before leaving, I asked Paul Symington about his plans after retirement, and he replied that he is eager to spend more time in his own vineyard, not far from Pinhão. It will be interesting to see how Charles Symington takes Symington Family Estates forward over the next few years, though I am pretty sure that this is not the last we have seen of his indefatigable cousin. After all, port is for life.

See the Wines in the Order Tasted

You Might Also Enjoy

Vintage Port – The 2016 Declaration, Neal Martin, June 2018

Cellar Favorite: 1948 Taylor Fladgate Vintage Port, Neal Martin, June 2018

Cellar Favorite: Blandy’s Madeira – Recent Releases, Neal Martin, March 2018

Cellar Favorites: 1870 & 1970 Centenario Colheita Tawny Port, Neal Martin, February 2018