Browse using the new Vinous website now. Launch →

Printed by, and for the sole use of . All rights reserved © 2015 Vinous Media

Vietti Barolo Rocche: A Historical Retrospective 1961-2011

Sometimes everything just works. That isn't always the case with older, artisan wines that can at times be moody, but on this night I had a feeling the late Alfredo Currado was looking down on us as we embarked on a search to understand the essence of his family’s iconic Barolo Rocche through seventeen vintages going all the way back to the inaugural 1961. Proprietors Luca and Elena Currado were on hand to add their invaluable insights as we travelled through the history of one of Italy’s most iconic wines.

The table is set

Dinner was at Vaucluse, Chef/Proprietor Michael White’s new French-inspired, upscale brasserie on New York’s Upper East Side. I have long believed that Italy is capable of producing world-class wines on a par with the best France, California and anywhere else has to offer. But Italian wines are often limited by the constraints of the Italian kitchen. For that reason, whenever possible, we host dinners featuring Italian wines outside of their more familiar habitat. That approach has never failed to produce stellar results. This night was no exception.

White and his team prepared a fabulous meal, while Wine Director Richard Anderson took great care of the wines. The bottles were left standing for a number of days before the event to allow sediments to settle naturally. We started opened the wines at 4:30pm. I tasted through every bottle myself. We had only one corked bottle. I chose to discard two other bottles that, while not corked, weren’t perfect. Everything was double decanted beforehand. Some of the wines from the 1980s needed more time in the decanter, but all the wines got a good bit of air. Provenance was as good as it can be. With the exception of the 1982, which was sourced from two different private collections, all of the wines were acquired from the estate. The only decade not represented, sadly, was the 1970s, only because of a lack of bottles. As is our custom, the wines were served in thematic flights rather than chronologically, which I feel keeps the palate engaged and makes for fascinating comparisons along the way.

Wine Director Richard Anderson prepares the wines

Historical Background

Vietti is one of Italy’s most historic wineries. Husband and wife Alfredo Currado and Luciana Vietti (Luca Currado’s parents) were pioneers in so many ways. They were among the first producers to bottle single-vineyard Barolo and to promote Piedmont and its wines abroad, especially in the United States. Alfredo Currado is also widely credited for rescuing Arneis from total obscurity in the 1960s.

I started drinking Vietti when I was a teenager. My parents had a wine shop and we sold many of the Vietti offerings. At the risk of dating myself too much, let me just say this was before prices for Barolo and Barbaresco exploded to levels that made them less accessible for a mid-week splurge. Later, as a struggling musician, I often turned to the Tre Vigne Barberas. The Scarrone and La Crena were reserved for special occasions. A few years later I had the opportunity to live in Italy. The dollar was strong and all the wines were readily available in the Vietti tasting room in pretty much unlimited quantities. To say things have changed since then is a massive understatement.

Alfredo Currado and Luciana Vietti, photographed the day Currado came home from the hospital after losing part of a finger to a destemmer

Today, Piedmont is living through a period of extraordinary prosperity. But it wasn’t always that way. In the 1950s, Piedmont was losing its young generation to the factories of Alba and Torino, where the lure of a stable income and an easier life away from the poor, decidedly rustic countryside proved to be irresistible for many. At the time, the price of a hectare of Dolcetto was roughly the same as that of a hectare of Nebbiolo designated for Barolo.

Inspired by the French concept of terroir, respected Italian journalist Luigi Veronelli urged Piedmont’s producers to recognize the distinctiveness of their vineyards. Up until the early 1960s, Barolo was made by blending fruit from different vineyards in the belief that each parcel had something unique to add to a blend; one site might contribute aromatics, while others might add structure, fruit and other desirable attributes. That approach, which is now, curiously, being rediscovered, yielded many spectacular wines, as readers versed in Barolo know well. But it was a different time in Piedmont. The goal of farming vineyards and making wine was quantity, not quality. Only a few estates bottled Barolo at all; most growers sold fruit to one of the large commercial firms such as Borgogno and Fontanafredda.

In 1961, Alfredo and Luciana Currado made their first single vineyard Barolo Rocche from the family’s prized hillside site in Castiglione Falletto. The same year, Beppe Colla also made a Barolo Bussia at Prunotto. Bruno Giacosa followed in 1964 with the first single-vineyard Barbaresco, his epic Santo Stefano Riserva. These three seminal wines changed the history of Piedmont forever.

The success of the early single-vineyard Barolos (and Barbarescos) brought considerable attention to Piedmont. Single vineyard wines would soon dominate over blends as the world discovered the Langhe and its endless shades of dimension. As interest in Barolo grew, especially through the 1980s and 1990s, a new generation of young growers began to estate-bottle their wines, mirroring a trend seen in Burgundy and other regions around the world.

Now in its fourth generation, Vietti remains very much a family affair. Winemaker Luca Currado, his brother-in-law Mario Cordero, along with their families and tightly knit staff, have taken the early groundbreaking work of Alfredo and Luciana Currado and built upon those successes, reaching an unprecedented level of consistency and quality across their entire range. Vietti is the only estate in Piedmont that owns vineyards in all eleven of the Barolo-producing villages. Many of the parcels are located in the region’s most historic and pedigreed sites.

Rocche di Castiglione’s steep incline. It’s easy to go down, but not so easy to get back up

Rocche di Castiglione

The village of Castiglione Falletto lies in the middle of the Barolo zone, where the soils from the two main periods – Serravallian and Tortonian – come together, often resulting in rich tapestries of soils that yield distinctive wines. One of the signatures of the best Castiglione Falletto Barolos is their ability to drink well relatively early and also age for decades. Castiglione Barolos are often intensely perfumed and have a silkiness to their tannins that is distinctive. All of those qualities find their highest expression in Rocche di Castiglione and nearby Monprivato. With the 2010 vintage, Rocche di Castiglione is known by its full name, but before then it was also often seen on labels as simply Rocche, which, among other things, caused confusion with other similarly named vineyards such as Rocche dell’Annuniziata in La Morra.

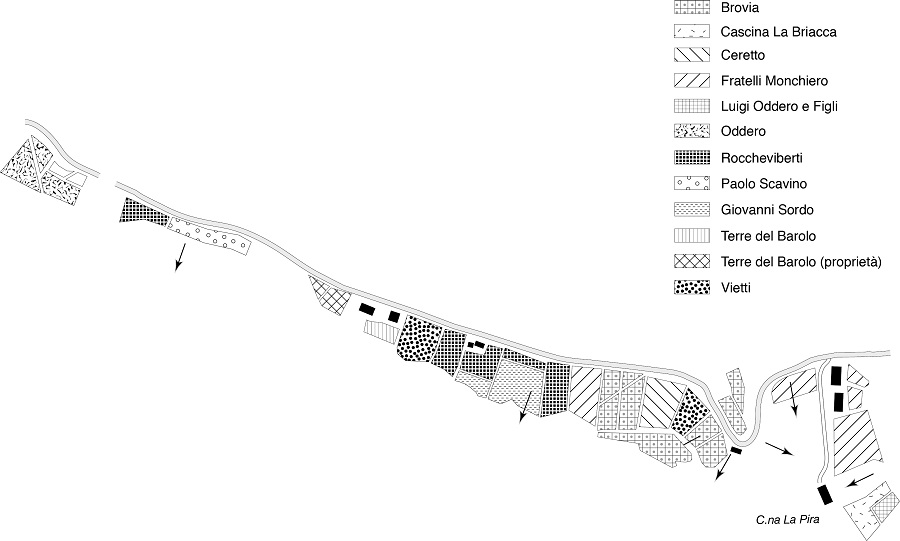

The Currado family owns two parcels totaling just under one hectare in Rocche di Castiglione, a steep, vertigo-inducing site outside the center of town. The original vineyard is the larger piece that lies in the direction of Monforte. According to Luca Currado, this parcel has been in the family for as long as he has records. Colloquially, the vineyard is still known as ‘Rocche di Natale’ after the farmer who previously owned the land.

Now shared between Vietti and Roccheviberti, this vineyard was formerly one large parcel. Currado observes that the clonal makeup in both holdings is exactly the same across the two large horizontal sections that run across the properties, which leads him to think the land was originally divided into upper and lower sections, but was later reconfigured to give both owners access to the main road above. The lower part of the vineyard is planted with an old variant of Michet, while the upper section is planted with a combination of Michet, Rosé and Lampia Nebbiolo clones.

In the mid 1980s, Vietti bought a second piece in Rocche that lies closer to Castiglione Falletto, near the bend in the road and nestled between Brovia’s holdings. It, too, is locally known by the name of its previous owner, in this case, Margherita. This parcel is also planted with an old variant of Michet, identified as such because the bunches have no wings. According to Currado, the soils are not markedly different between the two parcels; both are rich in the blue tufa/sand mixture that is typical of Rocche, with perhaps just a bit more sand in the vineyard on the Castiglione side.

Although Vietti’s Barolo Rocche has been an estate wine for some time, there was a period during which Alfredo Currado purchased grapes from his neighbors. Records are inexact at best (Piedmont is still Italy), but purchased fruit is almost certainly present in vintages through the mid 1990s with a production in excess of 5,000 or so bottles. For example, in 1986 Vietti made 5,300 bottles of the Rocche and that is after hail wiped out more than half of their crop. Similarly, production of the 1988 surpassed 7,000 bottles, while the 1995 came in around 6,500 bottles. Of course, none of the techniques that are used today such as green harvesting, bleeding and sustainable farming (which tends to naturally reduce yields) were common up until the 1990s, so information on labels alone can only tell part of the story. Today, Vietti makes closer to 4,000 bottles of Rocche, which is the norm for what is considered quality-driven farming and yields by present day standards.

Rocche di Castiglione, Castiglione Falletto, parcel by parcel. © 2016 Enogea, Alessandro Masnaghetti Editore. All rights reserved. Used with permission.

Vietti fans will also notice Cascina Briacca on the map. Briacca lies just off the road that leads to Roagna’s Cascina Pira. Alfredo Currado purchased grapes from this site for his Barolo Briacca from the 1970s through the early 1990s. The 1978, last tasted a few years ago, was still fabulous. One of the particularities of this site is that it was originally planted with the Rosé clone of Nebbiolo. In the late 1980s, the owner replanted the vineyard with clonal material that Alfredo Currado found less interesting. A few years later, he stopped working with the fruit.

The Four Periods of Vietti

In my view there are four distinct periods at Vietti going back to 1955, the oldest Barolo I have tasted from the Currado family. Up until the mid 1980s, the wines were made with the rudimentary tools that were available in Piedmont at the time. Alcoholic and malolactic fermentation were done entirely in cask and with no temperature control, an approach that led to distinctive, but at times also variable, wines.

Stainless steel tanks arrived in 1984. The ensuing wines were immediately more polished because of temperature-controlled fermentations in tank and the greater hygiene that steel allows. The shift can very easily be seen in this tasting by looking at the 1982 and then comparing it stylistically to the 1985, as well as the wines that follow.

The third period takes place in the mid 1990s as Luca Currado gradually introduced more modern techniques, including malolactic fermentation in French oak barrique, bleeding of the musts to obtain greater concentration, and a generally more extracted, oaky style.

Although Luca Currado grew up around the family winery, 1988 is the first vintage he was at the estate full time after having finished school. In 1990, Currado worked a harvest at Mouton Rothschild and spent the following year at Opus One in Napa Valley. It was a delicate time of transition at Vietti, as Currado’s sister, Elisabetta, was more involved at home than he was. Currado returned to the winery in time for the 1992 harvest, not exactly an auspicious beginning.

In his spare time abroad, Currado had done some marketing of the Vietti wines. Things were very different back then. “When I visited customers, they told me our Barolos were too lean,” Currado told me recently. “I saw things that are unimaginable today, like Conterno Monfortino being closed out in New York City. Our wines, along with those of Bartolo Mascarello, were being closed out in California.”

Back home, Currado wanted to experiment with more modern techniques. In 1992, Currado introduced French oak barriques for Barbera d’Alba Scarrone. A few years later, around 1996, Currado began using barrique for Barolo as well. “At the time, the 1990 vintage was all the rage. It was the beginning of the first Barolo craze. But it was the modern wines that were getting all of the attention. Like any young winemaker, I wanted to experiment. In 1994, we bought a large parcel measuring 2.7 hectares in Ravera. My father told me if I wanted to make a more modern Barolo, I could do it with the Ravera. Quite rightly, my father did not want me playing around with any of our signature Barolos. The relatively large size of Ravera made it more naturally suited to trying different things out.”

“I started to use the barrique for stabilization of color and also to give the wines more creaminess through stirring of the suspended lees,” Currado explains. “An added benefit is that CO2 acts as a natural preservative, so we need to add less SO2 during aging,” he adds. Most winemakers who do malo in barrique work with 100% new oak, which is considered more desirable for control and cleanliness, but at Vietti, Currado prefers to work with only a small amount of new oak. Over the years, the new oak and total amount of time the Barolos spend in French oak have both come down significantly.

Multimedia: A Conversation with Luca Currado

In 1999, Currado made his first Barolo from Ravera. I absolutely adored that wine. I tasted it when it was first released and bought it at the tasting room. Unfortunately, I drank all my bottles far too young, as was made painfully clear to me when I last tasted it a few years ago. “The Ravera was my most modern Barolo. It was vinified at slightly higher temperatures than was the norm, with less time on the skins than I was doing for our other Barolos. I left the wine in French oak for around 18 months, then finished the aging in cask, “ Currado told me.

I never thought the 1999 Ravera was an oaky Barolo. It may have been that the strong personality of the year and the site were both so prominent that they came through just the same. But by 2000, Currado was less enthusiastic. “I have never loved the 2000 Ravera, so after that vintage we stopped bottling it separately.”

Two thousand one is the next inflection point in a style that became more crystallized by 2004 and that continues today, naturally with further refinements along the way. Today, the Barolos see several weeks on the skins, with a classic submerged cap fermentation. Bleeding is used in vintages that are lacking natural concentration. Malolactic fermentations are still done in French oak, but with mostly neutral oak. The Barolos spend 2-3 months in barrique as opposed to the 8-9 that was common a 10-15 years ago. Curiously, the Ravera remains Currado’s most experimental canvas. In the late 1990s, it was the most modern Barolo at Vietti, today it is the most traditional because it does not see any French oak at all. Instead, all of the aging takes place in cask. This vertical provided a great opportunity to see all of those transitions firsthand and explore the full stylistic evolution that has taken place at Vietti over the last fifty years.

Pierre Péters’ 2008 Brut Cuvée Spéciale Les Chétillons

The Tasting

Reception – Passed Canapés

The just-released 2008 Les Chétillons is finally beginning to show something after a long period of being incredibly shut down. Bright and beautifully focused, the 2008 sets the mood for the night with its electric energy. The room is buzzing with anticipation.

Vaucluse Chef/Proprietor Michael White discusses the menu

Grilled Spanish Octopus; Chickpeas, Chorizo

To Start: 1986, 1988, 1995, 2011

The 1986 Barolo Rocche is superb. What a wine to start the night. Devastating hail in May wiped about two-thirds of the Barolo production and only a handful of producers bottled wine, but most of the wines that were made remain impressive. Bruno Giacosa and Bartolo Mascarello both told me they thought 1986 was a better vintage than 1985. Ever since then, I have actively sought out the wines. Vietti’s 1986 Barolo Rocche is an uber-classic wine for the vintage; dark, powerful and full of life. Conversely, I have never been able to get excited about 1988, mostly because the wines have developed unevenly. Vietti’s 1988 Barolo Rocche is a touch slender and the fruit is drying out, but, all things considered, it has held up fairly well. Any remaining bottles need to be finished.

One of the surprises of the evening, the 1995 Barolo Rocche is superb. Dark,

rich and intense, the 1995 comes across as a slightly gentler version of the

1996 that follows later in the evening. Luca Currado adds that macerations were

the longest-ever at Vietti at the time (50 days), yet there is something a bit

unpolished about the tannins that remains. The 1995s were greeted with a good

deal of fanfare when they were first released, no doubt partly because the

preceding four vintages were average to poor, but I have never found the wines

particularly exciting. Vietti’s Rocche is about as good as it gets. I am tempted

to say the 2011 Barolo Rocche is

another surprise, especially for attendees who had not tasted it yet. Soaring

aromatics, silky tannins and vibrant, saline notes all make the 2011 absolutely

delicious today. The 2011 will be even better in time, but it is a terrific

example of contemporary Barolo that does not need to be cellared for years or

decades to deliver pleasure.

Épaulettes; Rabbit & Reblochon Cheese Ravioli, Black Truffle

Years of Transition: 1996, 1999, 2001

All three wines in the next flight are terrific. The mid to late 1990s were a period of considerable change in Piedmont, as the differences between traditional and more modern-leaning producers were especially marked during this time.

The 1996 Barolo Rocche is dark, virile and imposing, all signatures of this super-classic vintage. Rose petal and tar notes give the 1996 much of its captivating appeal. The 1996 is the one wine in this tasting that did not respond well to aeration. In my view, the 1996 was never as beautiful as it was when the bottles were first opened. Readers lucky enough to own the 1996 are in for a fabulous experience, although I would suggest waiting another few years for the wine to come into its prime. The 1999 Barolo Rocche is the star of this flight, as it has all of the classicism of the 1996, but with a little more perfume and inner sweetness, both of which serve to flesh out the mid-palate nicely. What a vivid and utterly captivating Barolo the 1999 is. I have always had a weak spot for the vintage. When I taste the 1999 Rocche, I am once again reminded why.

Initially quite awkward, the 2001 Barolo Rocche takes a good few hours to come together. Now, fifteen years after the vintage, the track record for the 2001s is not as consistently brilliant as I had hoped. As a group, the wines are maturing faster and more unevenly than some of the surrounding top vintages, such as 1999 and 2004. Vietti’s 2001 Barolo Rocche is a good example of that. I very much like the wine’s demi-glace-like richness, but the bouquet only comes into focus after the wine has been opened for a number of hours. Even so, the 2001 gives the impression it will age faster than the 1999 tasted alongside it. These are pretty small quibbles, though, as all the wines in this flight are truly superb.

Épaulettes; Rabbit & Reblochon Cheese Ravioli, Black Truffle

Lotte Rôtie; Roasted Monkfish, Foie Gras Stuffed Morels, Potato, Red Wine

Modern-Day Icons: 2004, 2006, 2008, 2010

What a privilege it is to taste these four young, iconic Barolos side by side. Two thousand four is in my view, the first vintage that cements both Vietti’s present-day style and place among Piedmont’s elite estates. All four wines also show a clear thread that links them, something that is not evident in the surrounding flights.

The 2004 Barolo Rocche is pure silk on the palate. Like so many 2004 Barolos I have had recently, the Rocche is a bit subdued, but its class is impossible to miss. Sweet floral and spice notes give the 2004 its aromatic lift. This is Rocche at its most classic. I still remember tasting this wine from cask. It was striking back then and is every bit as captivating on this night. Structure and pure power are the signatures of the 2006 Barolo Rocche. This imposing Barolo is likely to take quite a bit of time to fully come together, but it is impressive tonight just the same. The wine’s explosive, vertical structure is the stuff dreams are made of. What a wine!

I have had the 2008

Barolo Rocche many times over the last few years and it has never been

anything less that impressive. Above all else, the 2008 seems to still be

growing. Intensely sweet and nuanced, the 2008 is utterly captivating. The

greatness of some vintages is immediately evident. Others take a bit more time

to fully reveal themselves. My impression is that the 2008 Rocche is still on

the ascent. Tonight, it is one of the most magnificent wines at the table. The 2010 Barolo Rocche is as alluring as it

has always been. Yes, it is young. Very young. But its greatness simply can’t

be denied. Vivid, precise and nuanced to the core, the 2010 simply has it all. Simply

put, the 2010 Rocche is an utterly profound wine that captures all of the nobility

of Barolo.

An unexpected surprise: attendees received this special Vietti boxed set (only 210 made) featuring Alessandro Masnaghetti’s Barolo MGA, The Barolo Great Vineyard Encyclopedia, plus historic information on the winery and the Barolo Rocche

Selle d’Agneau Grillée; Grilled Colorado Lamb Loin, Roasted Vegetables, Spring Onion, Mint Lamb Sausage

The Classics: 1982, 1985, 1989, 1990

These four stunning Barolos find Alfredo Currado at the peak of his powers. The 1982 is my favorite. A deeply expressive Barolo with captivating aromatics and remarkable nuance, the 1982 also the first glass I finish. I find much to admire in the 1985, although it is a slightly overshadowed in this flight. The 1989 and 1990 are a bit subdued relative to other times I have tasted those wines, but overall the flight is Magnificent. With a capital M.

What a treat it is to taste the four epic vintages of the 1980s side by side. The 1982 Barolo Rocche, from one of my favorite Barolo vintages, is stunning. An eccentric, wild Barolo, the 1982 possesses soaring aromatics, silky fruit and exceptional overall balance. There is something about the 1982 that is simply magical. I am not sure I can explain it with words, but this is my first glass I drink to the very last drop. The 1982 was one of the last wines at Vietti to be fermented in oak, before the arrival of stainless steel tanks. Today it is a gem from a bygone era. The 1985 Barolo Rocche seems to get a bit lost on this night, but to me it is a superb example of the year. Rich, ample and textured, the 1985 captures all the generosity and radiance of a vintage that most old-timers point to as the starting point as climate change brought about drier winters, warmer summers and less rain during harvest. The 1985 is one of my favorite wines for drinking now. A Vinous reader who enjoys the 1985 asks what current vintage is most likely to develop along the lines of 1985. For me, that vintage is 2007.

The 1989 Barolo Rocche is a bit reticent on this night. Although the 1989 is pretty, our bottles aren’t quite as explosive or intensely perfumed as the best examples can be. At its best, the Rocche is one of the finest 1989s. On this night though, the 1989 is merely outstanding. Much the same is true of the 1990 Barolo Rocche, which is very good, but also not quite as memorable as it has been in the recent past.

Selle d’Agneau Grillée; Grilled Colorado Lamb Loin, Roasted Vegetables, Spring Onion, Mint Lamb Sausage

Selection de Fromages

Back to the Beginning: 1967, 1961

Quite appropriately, the evening ends with two striking, fully mature Barolos from the 1960s. The 1967 Barolo Rocche needs quite a bit of air to show at its best. The bottles were opened a few hours before they were served, but that was not enough for the 1967. In the glass, though, the wine finds its balance pretty quickly. Next to the 1961, the 1967 has a bit more depth and slightly coarser tannins, but remarkable persistence for its age. The 1961 Rocche di Castiglione is faded in color but remarkably sweet, silky and nuanced on the palate, with an eternal finish and exceptional balance. It is in my view past peak, yet, all things considered, the 1961 has held up nicely. Interestingly, even sixty years ago, the label on this wine read “Rocche di Castiglione,” as the vineyard is known today, rather than the more generic Rocche, which was used until the revised names of Barolo vineyards went into effect with the 2010 vintage. Up until 1961, all Barolos were multi-vineyard blends. In 1961, Vietti and Prunotto made the first single-vineyard Barolos, wines that would go on to change the history of Barolo in the years and decades to follow. We are tasting an historic wine. And it is fabulous.

With the 1961 Barolo Rocche we come full circle to the beginning. I can’t think of a better wine with which to finish this truly moving and unique tasting.

See all the wines in the order tasted

You Might Also Enjoy

Article: Historic Piedmont: A Trip Back In Time, Antonio Galloni, November 2015

Article: 2004 Barolo: The Cream Rises to The Top, Antonio Galloni, May 2015

Article: Brovia – Barolo Rocche di Castiglione: 1982-2010, Antonio Galloni, January 2015

Article: Giacomo Conterno Barolo Riserva Monfortino 1970-2006 from Magnum, Antonio Galloni, May 2014

Article: Vietti: Barolo Riserva Villero – A Complete Retrospective 1982-2004, Antonio Galloni, August 2011

Multimedia: The Vineyards of Barolo – Rocche di Castiglione, Antonio Galloni, September 2014

Book: Barolo MGA, The Barolo Great Vineyard Encyclopedia, Alessandro Masnaghetti

-- Antonio Galloni