Browse using the new Vinous website now. Launch →

Printed by, and for the sole use of . All rights reserved © 2015 Vinous Media

The Last Frontier: The Nebbiolos of Alto Piemonte and Valtellina

BY ANTONIO GALLONI | JUNE 22, 2018

Capable of expressing the purest essence of site, vintage and producer style, Nebbiolo is without question one of the world’s elite red grapes. Skyrocketing prices and soaring demand make it increasingly difficult for consumers to find the best Barolos and Barbarescos. But the glories of Nebbiolo stretch far beyond those prestigious appellations. Readers will find a bevy of striking, captivating wines in Alto Piemonte and Lombardy’s Valtellina. For the sake of convenience, I have grouped the Nebbiolo-based wines of Alto Piemonte and Valtellina in a single article. Perhaps one day these two very distinct regions will boast enough quality minded producers to merit separate pieces.

Alto Piemonte – An Introduction

With the exception of Carema, which sits close to Valle d’Aosta, in the province of Torino, most of Alto Piemonte’s wine production is centered in the provinces of Novara and Vercelli, in the northern reaches of Piedmont. Volcanic soils and generally cool conditions (with respect to Barolo and Barbaresco) yield bright, focused red wines that have the underlying minerality and acid profile to age effortlessly for years, and in many cases, decades. At times, the wines can be a bit severe, though. In this regard, Alto Piemonte has benefitted greatly from climate change and generally warmer seasons that give the wines a bit more mid-palate richness than was once the case without fundamentally altering how the wines feel.

Today, Alto Piemonte has become trendy as wine lovers and industry professionals look for alternatives to Barolo and Barbaresco. But Alto Piemonte’s suitability for making world-class wines is hardly new. It may seem hard to believe, but in the 19th century Gattinara and not Barolo or Barbaresco, was Piedmont’s most famous red wine. Sadly, a prolonged period of crises ranging from phylloxera and other vine diseases in the late 1800s to the rise of industrial expansion, specifically within the textile industry in the early 1900s, caused vineyards in Alto Piemonte to be abandoned in favor of more profitable economic ventures. Gattinara became a DOC wine in 1967 and then a DOCG wine in 1990, but that was not really enough to bring back the appellation to its previous era of glory. I wrote my first article on Alto Piemonte more than a dozen years ago, in 2005 in Piedmont Report. I can still remember how depressed and backward the region was then.

There is no question that the most exciting development in Alto Piemonte is Roberto Conterno’s recent acquisition of Nervi in Gattinara. Nervi is the oldest winery in Gattinara and owns several choice vineyards, including Molsino. Producers of Conterno’s generation are increasingly tempted by outside projects. These winemakers are young, ambitious and well traveled. It is only natural they want to expand their horizons. Rodolphe Péters and Etienne de Montille have both set up operations in Santa Barbara. Dujac’s Jeremy Seysses consults for Presqu’ile in Santa Barbara, Flowers in Sonoma and Roederer in Anderson Valley. Jean-Nicolas Méo, Louis-Michel Liger-Belair and Jadot have all followed the early lead of Drouhin in Oregon. These are just a few examples. Roberto Conterno could have done any project anywhere in the world. His bet is on Italy, Piedmont and Nebbiolo. That is such a strong statement. Moreover, Nervi, which Conterno will run with his two young sons, Niccolò and Gabriele, sets up his family with a diversifying asset for the next generation, which is quite forward looking in a world in which historic family-owned estates are now real businesses that are subject to market forces that did not exist up until very recently.

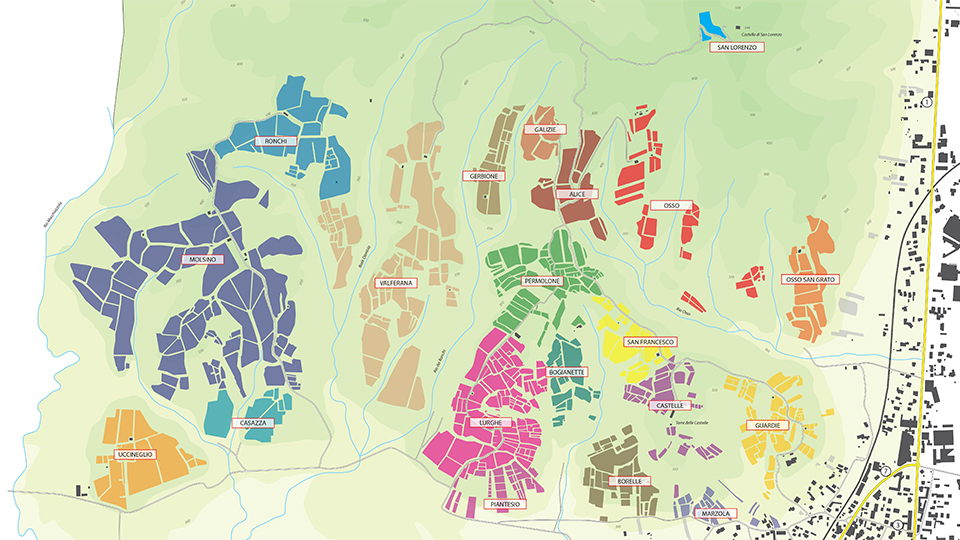

The vineyards of Gattinara are mostly concentrated on a single hillside. Excerpt taken from Gattinara DOCG: Vineyards and Cellars by Alessandro Masnaghetti, ©2016. Used with permission

The Grape Varieties of Alto Piemonte

Nebbiolo, known locally as Spanna, reigns supreme in Alto Piemonte and is the main grape in all of the region’s appellations. In the Langhe’s prestigious Barolo and Barbaresco production zones Nebbiolo is found alone, but in Alto Piemonte, Nebbiolo is almost always blended with other indigenous varieties such as Vespolina, Croatina and Uva Rara, which results in wines that can be quite complex and multi-dimensional. Although each of Alto Piemonte’s appellations is distinct, we can observe that Nebbiolo and Nebbiolo-based reds from Alto Piemonte are generally finely sketched, somewhat slender wines with more of an acid-driven nervosity than is found further south in Barolo, Barbaresco and Roero.

Vespolina is most often seen as a complement to Nebbiolo in many Alto Piemonte wines. In recent years, a small number of growers have begun to bottle Vespolina, which gives us an opportunity to see how the variety behaves on its own. Most Vespolinas are intensely floral, savory and lifted, with more of a dried (rather than fresh) fruit character and mid-weight structure.

Croatina is known for its deep color and intense dark fruit. Croatina is another variety that is most often seen as a complement to Nebbiolo in Piedmont (and also Corvina in Veneto), but that is increasingly bottled on its own. The best Croatinas I have tasted are fleshy, beautifully resonant, layered wines.

Alto Piemonte – An Overview of Appellations

Alto Piemonte can be broken into eight distinct appellations: Gattinara, Ghemme, Boca, Bramaterra, Carema, Fara, Lessona and Sizzano. As a reminder, ‘DOC’ (Denominazione di Origine Controllata) regulations set the geographic boundaries for each area of production, and also prescribe a set of conditions that govern the production of wines, ranging from permitted grape varieties, yields, minimum aging requirements and a host of the other variables. The ‘G’ (Garantita) in DOCG adds the further provision that wines must be tasted and approved by a panel in order to carry the DOCG designation.

Gattinara/Gattinara Riserva DOCG: minimum 90% Nebbiolo, maximum 10% Uva Rara (Bonarda di Gattinara), maximum 4% Vespolina.

Ghemme/Ghemme Riserva DOCG: 85% Nebbiolo, maximum 15% combined of Uva Rara (Bonarda Novarese) and/or Vespolina.

Boca/Boca Riserva DOC: 70-90% Nebbiolo, 10-30% combined of Uva Rara (Bonarda Novarese) and/or Vespolina.

Bramaterra/Bramaterra DOC: 50-80% Nebbiolo, maximum 30% Croatina, maximum 20% combined of Uva Rara (Bonarda Novarese) and/or Vespolina.

Carema/Carema Riserva DOC: 85-100% Nebbiolo, up to 15% other red grapes.

Fara/Fara Riserva DOC: 50-70% Nebbiolo, 30-50% combined of Uva Rara (Bonarda Novarese) and/or Vespolina, maximum 10% other red grapes.

Lessona/Lessona Riserva DOC: 85-100% Nebbiolo, up to 15% combined of Uva Rara (Bonarda Novarese) and/or Vespolina.

Sizzano/Sizzano Riserva DOC: 50-70% Nebbiolo, 30-50% combined of Uva Rara (Bonarda Novarese) and/or Vespolina, maximum 10% other red grapes.

Valtellina – An Overview

Nebbiolo finds entirely different shades of expression in Lombardy’s Valtellina, a thin strip of steep, terraced vineyards above the Adda river that has the town of Sondrio as its center. Known locally as Chiavennasca, Nebbiolo in Valtellina is capable of striking wines endowed with real personality. The heart of the appellation unfolds in the districts of Sassella, Grumello and Inferno, which produce many of the most pedigreed wines of the region. Valtellina reds are medium-bodied in structure and aromatically penetrating, especially those grown in some of the higher-altitude sections. Of the three main subzones, Sassella has a reputation for producing the most elegant wines, while Inferno is known for its richer, more enveloping reds. I am not sure those distinctions always hold as much as one might like them to, but there is no question that the finest Valtellina wines are deeply intriguing.

Whereas in Alto Piemonte each appellation has its own specific production guidelines, Valtellina is organized into a clear hierarchical qualitative pyramid of appellations that consists of the entry-level Rosso di Valtellina DOC, six DOCGs – a straight Valtellina Superiore plus the six subzone Valtellina Superiore DOCGs of Maroggia, Sassella, Grumello, Inferno and Valgella – and the top-of-the-line Sforzato DOCG. The varietal mix for all of Valtellina’s DOC/DOCGs is the same: 90% Nebbiolo and up to 10% other authorized red grapes. Naturally requirements with regards to yields, alcohol levels, aging and other variables become more stringent as one moves up the quality ladder. Sforzato sits at the pinnacle of the quality pyramid in Valtellina. For Sforzato, the fruit is air-dried, Amarone-style, for a few months before being crushed around mid-December, which yields a wine with the aromatic nuance and structure of Nebbiolo, but a level of textural richness that leans in the direction of Amarone without being as overt as those wines can be. Sadly, production for Valtellina’s reds is tiny, which means they will almost certainly remain of interest and accessible only to the most passionate of Italophiles. In a world where nothing is really private anymore, a little secret is not such a bad thing after all.

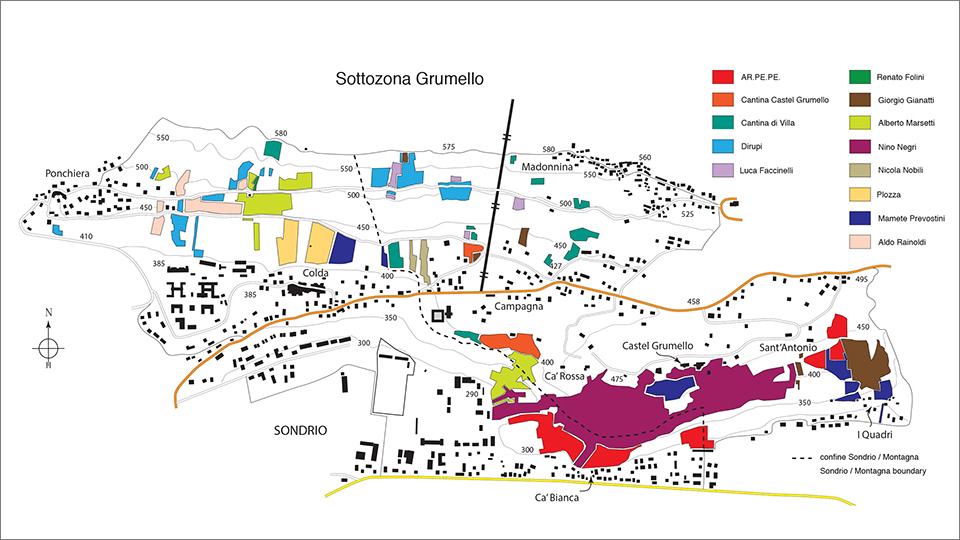

The Vineyards of Valtellina’s Grumello district as seen in Valtellina Superiore and its Subzones, by Alessandro Masnaghetti, ©2015. Used with permission

You Might Also Enjoy

Alessandro Masnaghetti Viticultural Maps

Piedmont’s Affordable Gems, Antonio Galloni, June 2018

2014 Barolo: Surprise, Surprise…, Antonio Galloni, February 2018

2014 Barbaresco: An October Surprise, Antonio Galloni, October 2017

1996 Piedmont: The Proof is in the Pudding, Antonio Galloni, October 2017

2013 Barolo: The Late Releases, Antonio Galloni, October 2017

Piedmont's Finest Eating Destinations: 2017 Edition, Antonio Galloni, October 2017

La Festa del Barolo 2017, Antonio Galloni, October 2017

Piedmont: Top Values and Everyday Gems, Antonio Galloni, February 2017

2013 Barolo: Sublime Finesse & Elegance, Antonio Galloni, February 2017

Show all the wines (sorted by score)

- Antoniolo

- Ar.Pe.Pe.

- Boniperti

- Cantalupo

- Cantina Produttori Nebbiolo di Carema

- Castello Conti

- Centovigne - Castello di Castellengo

- Colombera & Garella

- Davide Carlone

- Fay

- Ferrando

- Francesca Castaldi

- Giuseppe Rainoldi

- La Palazzina

- Le Piane

- Le Pianelle

- Mamete Prevostini

- Massimo Clerico

- Monsecco

- Nervi-Conterno

- Nino Negri

- Noah

- Proprietà Sperino

- Rovellotti

- Tenute Sella

- Tiziano Mazzoni

- Travaglini

- Vallana