Browse using the new Vinous website now. Launch →

Printed by, and for the sole use of . All rights reserved © 2015 Vinous Media

An Introduction to Piedmont Report

December, 2004

Welcome to the first issue of Piedmont Report, the Consumer’s Guide to the Wines of Piedmont. My goal is to provide not only extensive tasting notes of current releases, but also to take you into the vineyards and cellars of this incredibly fascinating region. For many consumers, the large number of producers and vineyard designations in Piedmont makes gaining a familiarity with the region a daunting task. I hope to make that easier. From time to time I will also write about thematic vertical tastings that explore one particular dimension such as the wines of a specific vintage, vineyard, or producer.

Piedmont is often viewed as one winemaking region, when in

my opinion, it is a collection of small regions, each with its own

characteristics. I will examine the

differences between Barolo and Barbaresco, take a closer look at the wines from

the area around Asti, the Dolcettos from Dogliani, and the Nebbiolos from the

northern Piedmont towns of Gattinara and Ghemme. This journal is written for people who love

the wines of Piedmont and those who have an interest in learning more about the

region.

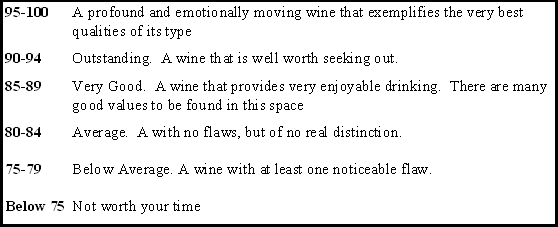

The Scoring System

I assign points to each wine on a 100-point scale. My score is an overall score which reflects a

wine’s expression of its varietal, vintage, terroir, aging potential, and

distinctiveness. I am also looking for

structure, length on the palate, persistence of the finish and overall balance.

Some of these qualities are difficult to articulate, but I believe the

experienced taster can discern the differences between wines that are good,

from those that are outstanding from those that are truly memorable. No scoring system is perfect, including mine,

but I do feel that an overall score best captures both my tasting approach and

my impressions about a given wine.

Scores are intended to reflect a wine’s potential at maturity. Wines tasted from barrel are scored within a

range, reflecting the reality that these wines are not finished products. Scores for wines tasted from barrel are

indicated in parentheses.

Assessing young Dolcetto and Barbera is admittedly not

terribly difficult in relative terms.

Tasting young Barbarescos and Barolos is another thing altogether. The high alcohol levels and tannins these

wines often present when young can make the wines very challenging to

evaluate. In addition, Barolo and

Barbaresco are richly structured wines that are made to accompany similarly

rich dishes. Wines can sometimes appear

to be very austere and closed in a blind tasting but then are fantastic when

paired with the right cuisine. By

definition, a focused tasting removes these wines from their natural habitat,

so tasting notes and scores should be taken as a general indication and not as

gospel. In short, Nebbiolo is very tough

to judge when young and what I offer is only one opinion. I tend to be conservative, so my scores

should be interpreted as a lower bound.

Ultimately, the tasting notes will tell you much more about what I

thought about a wine, especially compared to wines of the same type and/or

vintage. I rate every wine I taste, so

if a particular wine is not included under a producer, I simply did not get a

chance to taste that wine. In

conclusion, the best way to learn about the wines is to taste them as often as

possible, preferably in a setting organized around a theme, such as vintage,

cru, or producer. The most rewarding

aspect of a passion for wine is learning to trust your own palate.

Readers should note that I am personally responsible for all

of my travel expenses, including lodging, transportation and meals. I do accept sample bottles for the purposes

of tasting. I have no interest, either

direct or indirect, with any winery in Piedmont Report, nor am I personally

involved in any aspect of the wine trade.

How I Conduct Tastings

I feel it is important to visit the wineries, and to taste

each producer’s wines in the traditional order, which is from most accessible

to most structured. Visiting the estates

is crucial to learning about the winemaker’s philosophy and about the specific

terroirs a producer works with. I also

find it instructive to taste wines from barrel, to walk through the vineyards,

and to taste harvested fruit. I want to

get inside the wines as much as possible.

Recognizing that tasting with the producer can influence a critic’s

opinion of a wine, I also feel it is essential to conduct tastings in

single-blind conditions, so, where possible, many of the wines in this report

were grouped together for peer group blind tastings at my home. Scores, if they were different in the two

settings, were averaged and rounded to the higher number.

I do not participate in trade tastings, mostly because I need a calm work environment and I like to control the amount of time I spend with each wine. Barolos and Barbarescos in particular often require a great amount time and patience from the taster. For Barolos, Barbarescos and other richly structured wines it is my practice to re- taste each wine at least once and often more than once.

A Note on Barrel Tastings

Whenever possible I take the opportunity to taste wines from

barrel. Barolo in particular, with its

minimum of two years wood aging and one year of bottle aging affords a unique

opportunity to see how a wine develops over time. While tasting barrel samples is a valuable

component of understanding a given wine, I offer the following caveats to

readers in interpreting my notes: The

first of these regards temperature.

Wines tasted directly from tank or barrel are often colder than normal

serving temperature so the full range of aromas and flavors may be muted. Cellars are dark places and color is hard to

gauge accurately. For wines aged in

barrique, a barrel sample is really only representative of that specific

barrel. Given that the final wine will

be a blend of many barrels, the bottled wine may differ from that which was

tasted from barrel. Wines that have been

recently racked may also be showing the temporary negative effects of being

moved. Most importantly, fining and

filtration during the bottling process may negatively affect a wine.

Nevertheless, I find barrel tasting to be a critical aspect of assessing the quality

and evolution of the wines of a given producer and/or vintage. I do not give

drinking windows for wines tasted from barrel as the wines are not finished

products.

A Note on Drinking Windows

My drinking windows should be interpreted as the window for

peak drinkability and not how long specific wine might last and be in good

shape. My own preference is to drink

wines while they are still on the upward trajectory of their aging curves. In opening a bottle I prefer to err on the

side of youth rather than on the side of excess age. There is nothing worse than carefully

cellaring a wine for years, only to open a bottle and find it over the

hill. Some palates may prefer wines

with more age on them than I do.

While it is relatively easy to have some idea of when a wine

might start to drink well, it is much more difficult to know how long a wine

will stay at its peak. It is hard enough

for producers themselves to estimate how long their wines will age, let alone

for an outsider such as myself. Based on

over 15 years of experience in tasting these wines I have provided my best

guess as to when the wines will show at their best but readers should keep in

mind that any attempt to assign drinking windows is much more an art than it is

a science.

In general I prefer to drink Dolcettos within two to three

years of the vintage, while the wines still have the freshness that is their

chief attribute. For Barbera, I think

the wines show best when consumed five to seven years after the vintage. As they age, Barberas start to lose their

inner core of fruit, and my experience has been that most of these wines

decline rather quickly. There are

exceptions of course, but the number of sublime, aged Barberas I have tasted is

very, very small.

Evaluating drinking windows for Barolo and Barbaresco is

much more challenging for several reasons.

The first is that the state of winemaking has improved significantly

over the last fifteen years. As one

producer told me recently, “1990 was a vintage where the wines made themselves;

we had no idea what we were doing. There

wasn’t the attention to detail and level of care, both in the vineyards, and in

the cellar, that we have today.” Thus

tasting a given producer’s wines from an older vintage is not a terribly

reliable way of telling how today’s releases might age. To make matter more confusing, the area is

full of many small producers who have only been making high quality wines for a

few years, and have no long-term track record.

Most importantly, though, is that personal taste plays a

huge role in determining when a wine will be at its best. I enjoy Barolos and

Barbarescos both when young and old and find that following the evolution of a

given wine over the years can be a fascinating as well as rewarding experience. In general terms, Barolos start to become

approachable around age 7-10 and the best wines will age gracefully for

decades. Wines from hot vintages like

1990, 1997, 1998 and 2000 are typically ready to drink sooner while those from

more classic vintages like 1989, 1996, 1999, and 2001 take longer to reach

maturity, although other important variables such as terroir and the producer’s

style are also factors. I find that the

‘sweet spot’ for Barolos, the age where secondary and tertiary flavors have

developed, but the wines still have plenty of fruit, seems to be around age

15-20. Barbaresco is a wine that is

generally ready to drink earlier than Barolo, and I have found that most wines

are at their best within 7-12 years after the vintage. Lastly, proper cellaring conditions are

critical in insuring that Barolos and Barbarescos age properly. With good storage the wines can keep for many

years, even after reaching maturity.

There is a misconception that wines aged in barrique are

more accessible and immediate than wines aged in cask. This is a myth, or at least a gross

oversimplification. The readiness of a

wine is in reality much more producer-specific and vintage-specific. Thus there are some wines aged in barriques

which are approachable when young and others that require more patience, just

as with wines aged in cask. Critics of

modern-styled Barolos like to claim that wines made with short fermentations

and aged in barrique are not age-worthy, but as the first of these wines have

begun to enter maturity, it has become clear that ageability is a result of the

winemaker’s skill and not of the tools he or she uses.

Traditional versus Modern

Much has been written about “traditional” versus “modern”

wines in Piedmont. I am often asked my

opinion on the subject and the short answer is I have no bias towards one

approach or another. I appreciate the

merits of both styles of wines. In

reality there are many more subtleties in Piedmont than the overly simplistic

“traditional” versus “modern” framework can capture. Over the next few issues of Piedmont Report I

will explore in detail the many dimensions that define winemaking in both

styles, with the goal of shedding some light on the topic and moving the

discussion forward, away from rhetoric and hopefully towards a real

understanding of the wines.

Purchasing Strategy

As most everyone knows by now, Piedmont saw an unprecedented

string of fantastic vintages from 1996 to 2001. At the same time the region’s two main

export markets, the US and Germany, have stumbled and are importing much less

wine than just a few years ago, when estates had all their production not only

reserved but paid for in advance. What

is clear is that under the current macroeconomic conditions, there just isn’t

enough worldwide demand for the wines of the region. Cellars in Piedmont are literally full of

unsold wine. The situation is especially

acute in Barolo, which releases its wines a year later than Barbaresco, and

therefore has one more vintage’s worth of production in the cellars. Many producers have told me that their

importers simply skipped over the 1999 vintage after the Wine Spectator’s

perfect rating of the 2000 vintage. This

all adds up to a significant amount of unsold wine in the pipeline.

In Italy producers have been reluctant to lower prices,

because they feel consumers will feel they were being overcharged in the past,

so locally prices have remained fairly stable.

To sell wines in export markets, however, producers have had offers free

cases with orders to stimulate demand, effectively lowering the per bottle

cost. Hopefully the end consumer will

at some point start to benefit from this trend.

In the US, the continued weakness in the dollar rightly

worries anyone buying imported wines as well as other goods. My own view is that things are not as bad as

might be expected, at least for the private consumer. No estate has been immune

to the economic downturn. Except for a

few collectible wines or those with very high ratings, the vast majority of

wines will be available at some point at a favorable price. In fact, the reason

I don’t specifically identify wines that are good values is that a value-priced

wine purchased at full retail may actually cost more than a premium wine

purchased on sale. As always, it pays to

shop around and to be opportunistic as there are many great deals to be had.

In terms of Barolo and Barbaresco, my suggestion for

consumers is to purchase wines from hotter, riper vintages such as 1997, 1998

and 2000 vintages for near-term consumption while looking for wines from more

classic vintages such as 1996, 1999, and 2001 for cellaring. Among recent vintages of Barbera I think 2001

is truly special, with many wines possessing great balance and elegance while

2003 appears to be have very good potential for super-ripe wines. Dolcetto is a bit trickier in 2003, it pays

to taste before buying, as many wines are overly hot and alcoholic. I will address vintages in more depth in

Issue 2 of Piedmont Report.

About the Author

I have been involved with wine in one way or another for

about as long as I can remember. I grew

up in a family where food and wine were very important; there was often a

bottle of wine on the dinner table. My

grandfather was passionate about French wines and he introduced me to the wines

of Bordeaux, Burgundy and the Rhone, which he loved so much. I recall writing a paper on French wines for

my high school French class…..a sign of things to come.

Later, my parents opened an Italian food and wine shop

(which they have since sold) and it was there that I really became interested

in Italian wines. I spent many weekends

and holidays working at the shop and I had the chance to taste many of that

country’s best wines on a regular basis.

We also spent many family vacations in Italy, discovering the cultures

of various regions. It was a great education. After college I spent some time waiting

tables at a few of the better restaurants in the Boston area. During this period I had the opportunity to

further my knowledge of wine, especially American wine.

The first time I visited Piedmont I immediately fell in love with the region, its culture and its people. I was especially struck by the passion and dedication of the winemakers I met. A few years later, my career in the financial services industry took me to Milan, where I lived for three years. I spent most of my free time touring the winemaking regions of Italy. Much of that time was spent in Piedmont, visiting with producers, learning about the vineyards and tasting as much as possible.

-- Antonio Galloni