Browse using the new Vinous website now. Launch →

Printed by, and for the sole use of . All rights reserved © 2015 Vinous Media

Bordeaux In Excelsis

BY NEAL MARTIN | JUNE 26, 2018

WARNING: The article you are about to read contains more perfect wines and perfect scores than any published throughout my entire professional career. Readers with nervous dispositions or phobias towards rare, legendary and priceless wines are advised to stop reading immediately. Do not go any further. Press “Back” on your browser and read about delicious Sauvignon Blanc from New Zealand or Provençal Rosés. Forget this report exists. The evening described never happened. That’s right. It’s just a work of fiction. Just an infantile wine writer fantasising about his ultimate Bordeaux tasting like everyone in idle moments.

But you see, the event I am about to describe did occur. Me, one of a dozen attendees that bore witness to one of the greatest line-ups of Bordeaux ever assembled. An evening bejeweled with more “perfect” fermented grape juice imaginable under my own strict criteria. Suffice to say, it is unlikely to be repeated. I kept pinching myself. Was this really happening? Did I just drink that? Is that really the next bottle?

The theme was simple. As part of his International Wine & Business program of events, Omar Khan showcased the five mature First Growths at the peak of their powers – epochal wines that represent the snow-capped peaks of the 20th century. Bordeaux in excelsis. They were served not as thimblefuls that evaporate in seconds, rather as full glasses that were marveled, observed, juxtaposed and discussed over the duration of an entire evening. On paper, given château and vintage reputations, the wines would surely not match expectations.

True. These wines did not match my expectations.

They surpassed them.

Two germane questions must be discussed before broaching the wines:

What is a First Growth?

What is a perfect wine?

If any article is going to answer those questions, then you are reading it now. Skip the discussion if you wish and scroll down to my exaltation of the wines, however, in doing so you will not fully understand the criteria applied and my sentiments when making a statement as bold as: “This is perfection”.

What is a First Growth?

To this writer a First Growth is more than the quartet bestowed top ranking in 1855: Lafite-Rothschild, Latour, Margaux and Haut-Brion, joined by Mouton-Rothschild in 1973 after years of petitioning by Baron Philippe de Rothschild. The origins of the 1855 classification is something as perfunctory as a marketing strategy to promote Bordeaux as part of the Great Exhibition, the hierarchy determined by something as banal and yet crucially, as indisputable and objective as average prices over the prior decade. The immutable nature of the classification cemented its hierarchical sway over the Left Bank, becoming its foundation that exists until now and forever more. Nowadays, a First Growth is simply interpreted as “the best”. That isn’t implicitly true, as anyone who has tasted blind will confirm. However, if you examine their track record over decades then you must accept that there is much veracity in the classification, especially at the very highest level, to the chagrin of everyone gazing up enviously from below. The gap between the First Growths and “the rest” is vast, if not in quality per se, then certainly in perception. The gap has grown since fine wine reinvented itself as a luxury item; after all, the first rule of a luxury brand is to be considered “the best”. This has manifested an “us and them” scenario, an exclusive club where entry is barred for all but four, then five.

The bottles served on one memorable evening. One of those instances when you need a wide angle lens.

Personally, I seek a definition that goes beyond a one-dimensional concept of being the best. What qualifies that exactly? Surely more than whatever cost the most in the mid-19th century or what ticks more boxes. A sage friend once opined: “A true First Growth must produce a wine that transcends everything, including the other First Growths, once every decade”. Think about that: 1945 Mouton-Rothschild, 1953 Lafite-Rothschild, 1961 Latour, 1989 Haut-Brion and 1996 Château Margaux. For this writer, the stipulation is far more meaningful than a pecuniary value that can be manipulated and skewed/exaggerated by investment motives. In these days of “haut couture” vineyard husbandry, state-of-the-art wineries and limitless money, the First Growths are expected to create nothing short of excellence. Yet in my experience there is often one born with that indefinable edge, that intangible “je ne sais quoi” that warrants an additional but crucial point and maybe that magic three-digit number that denotes...

...perfection.

Ah, perfection. I disagree with those whose scale ends at “99” and/or renounce the existence of perfection. If you drink, let’s say, 1870 Lafite-Rothschild or 1945 Mouton-Rothschild and afterwards declare: “You know those two wines could have been better...” then please explain, exactly how? In my opinion, though refuseniks would deny it, their recalcitrance is little more than a self-aggrandizing point of principle rather than objectivity.

Their “99” is just “100” dressed in different digits. Both represent the highest number a wine can achieve.

Assuming perfection does exist then what are the criteria? Writer Andrew Jefford once wrote a perspicacious column that proposed some professionals interpret perfection/100-points as a plateau whilst others interpret it as a snow-capped peak. Picture those landscapes. The former perceive perfection as a platform that can be occupied by a number of high-performing wines, a priori, a vintage can potentially manifest a large number of perfect wines. The latter see perfection as the pointed summit where there is only room for a solitary wine, one that imperiously peers down on everything else.

That fits my idea of a perfect wine.

I want to qualify my viewpoint with one other condition that I expounded a few years ago. A perfect wine must not provoke one iota of doubt. If there is just one speck, then regretfully, it is not perfect. That sounds nitpicking and ridiculous. However, on rare occasions that I have encountered bona fide perfection, then I experience a paradoxical sense of clarity in judgment. Such wines are unequivocally perfect and that word is employed with an almost embarrassing rock-solid confidence.

So let us be clear. In my view...

A perfect wine is not complex but profound.

It redefines all previous notions.

It defies logic. It breaks rules.

It engages not just a euphoric sensory reaction, but transports you to a spiritual nirvana that no other beverage could ever comprehend.

A perfect wine is indelibly etched upon your memory, a benchmark against everything is judged henceforth.

A wine meriting a perfect score is not by dint of power, elegance, precision, length, longevity or even complexity, though it may possess all those virtues. It is an alignment of all those factors that unlocks something deep inside: an innate reaction akin to gazing up in awe at the Sistine Chapel, Glenn Gould playing The Goldberg Variations and falling in love.

Last but not least, there is no such thing as a perfect wine, just a perfect bottle. That maxim still rings true. Tonight, Bacchus was smiling upon us, since there was no TCA and a majority of bottles fired on all cylinders.

So let’s discuss them.

The Wines

Omar Khan had been assembling the wines over a long period of time, not least because sourcing a legitimate 1945 Mouton-Rothschild with sound provenance takes patience. Naturally, this is one article where you have to keep a lookout for possible fakes. I inspected as many of the bottles, labels and corks myself. I also had the luxury of tasting around one-third of these wines several weeks earlier at verticals of Lafite-Rothschild and Latour (Vinous readers with either be elated or horrified to know that these will follow as parts two and three of this First Growth “triptych”.) In addition, I had encountered many of these wines previously, often on multiple occasions including ex-château examples and therefore I was vigilant to anything that might be awry.

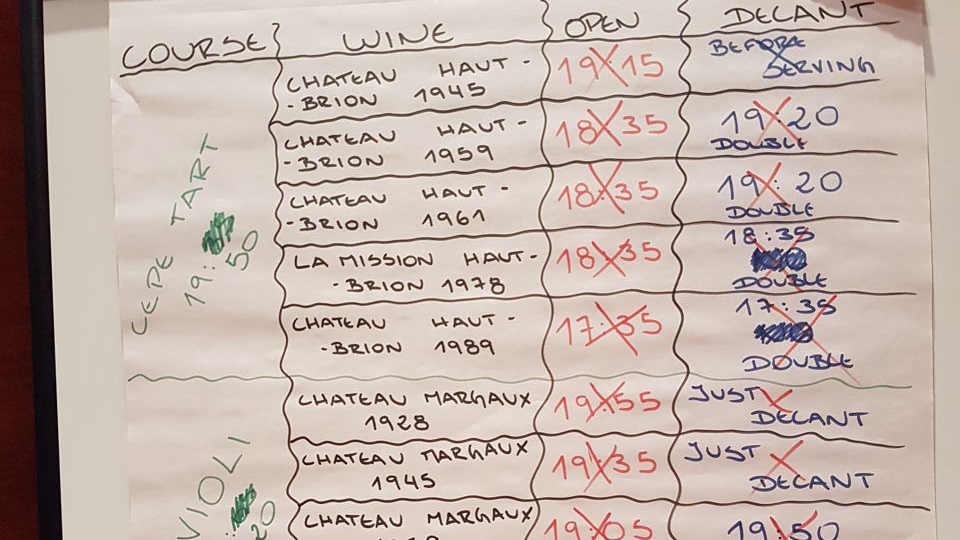

The meticulous detail for serving each wine so that sommeliers knew when to open and/or decant bottles. They did a fantastic job handling such rarities.

Château Haut-Brion

After a glass of exquisite 1973 Dom Pérignon, the first flight entered the Bordeaux city suburbs for a visit to Haut-Brion. This venerable First Growth, the only one located outside the Médoc, is often the pet-favourite of many oenophiles, attested by a recent thread that I instigated on Your Say, the Vinous reader forum. If a First Growth were measured by the sheer pleasure it gives (and many would argue “what else counts?”) then Haut-Brion would be top of the list. That is because it offers the best of two worlds: the structure and nobility of the Left Bank with the sumptuousness and sensuality of the Right. At its best, Haut Brion (and for that matter its sibling La Mission Haut-Brion) is more than a sum of its parts, an apt expression with respect to the majestic 1989 Haut-Brion.

The fact that the 1989 Haut-Brion was poured first gives you an idea of the epic scale of this momentous evening. Jean-Bernard Delmas, father of present winemaker Jean-Philippe, oversaw a sensational wine, one of the few that unites professional critics and consumers in a chorus of praise. I have been fortunate to drink this over a dozen times, around half worthy of that emotive word: perfection. In fact, this was one of the best bottles I have encountered despite one or two quibbles about an initial greenness that was subsumed as it morphed in the glass. It is a monumental, multi-faceted wine... Should I opine here that the 1989 La Mission Haut-Brion is snapping at its heels and may ultimately surpass it? No, I will leave that for another time.

Second up, the 1961 Haut-Brion, Jean-Bernard’s maiden vintage after succeeding his father as régisseur and the same year that the château took the revolutionary decision to dispense with the old wooden vats and became the first Grand Cru to install stainless-steel. Jean-Bernard remained adamant throughout his career that stainless steel was better than wooden vat. The 1961 Haut-Brion ranks amongst the top five of that epochal vintage, a wine of immense depth and structure, astonishing complexity and, at 57 years of age, life-affirming freshness and vitality, yet with a breeding before which you must genuflect. This was juxtaposed against the 1959 Haut-Brion, one of the final vintages made by Jean-Bernard’s father Georges Delmas in the original wooden vats. This stunning companion to the 1961 is perhaps not quite as riveting since it does not possess the same awe-inspiring grandeur, yet it is so sumptuous, exotic and sensual that you cannot help but grin. To complete the quartet: the 1945 Haut-Brion, another gem also courtesy of Georges Delmas who made every vintage from 1921. This is like the only previous bottle that I have encountered, a spellbinding and bewitching wine once it opened in the glass. Sure, the 1945 Mouton-Rothschild is the most famous wine that year. However, one could argue that the 1945 Haut-Brion is more sublime and perhaps nuanced.

So, 1989, 1961, 1959 and 1945...I did warn you, didn’t I?

Château Margaux

We move up the D2 and reach the Médoc. Château Margaux has the most seductive and perfumed bouquet, with a signature scent of crushed violet. It possesses some of the finest tannins amongst the First Growth and a beguiling purity. It is also perhaps the most sensitive First Growth and, as such, in my experience more prone to the vagaries of the growing season. André Mentzelopoulos purchased the property in 1978 but tragically died two years later, whereupon his daughter Corinne took over and took Château Margaux to the position it enjoys today.

The 1982 Château Margaux predates the arrival of the late Paul Pontallier by one year. A famously high-cropping vintage, such was the volume that there were insufficient vats to ferment the fruit upon arrival, necessitating an almost first-in, first out approach, which prompted Pontallier to request for a renovated and expanded vat-room. Often compared against the 1983, this is one of the finest 1982s that I have encountered, replete with that signature violet scent, astonishing precision and so much concentration that it ridicules that dog-eared notion that high yields cannot engender great wine in particular growing seasons. The highlight of this second flight comes courtesy of the 1959 Château Margaux, which, mirroring Lafite-Rothschild, has always been superior to the 1961. Pierre Ginestet had spent years investing in the estate and it paid dividends here. There were in fact two château bottlings in November 1961 and May 1962, so the different durations of élevage rendered different wines. This was a common practice at the time and, as far as I know, it is impossible to tell the two bottlings apart. Ginestet oversaw a wine that is still pixelated in terms of clarity, with breath-taking delineation and a poised yet intense finish that is impossible to put into words. It stands as one of the greatest 1959s, the last great Margaux before a slump in fortunes during the following two decades. (Incidentally, many people blame Pierre Ginestet for the decline although I heard another story that shines a very different light – I shall relate it another time.)

The 1945 Château Margaux serves as a reminder that this haloed vintage did not produce a royal flush of brilliant wines. Do not forget that in 1945, the perfect growing season coincided with many under-nourished vineyards, a lack of investment, out-dated and sometimes decrepit wineries and a lack of expertise on the ground. Fernand Ginestet who had been accruing shares since 1935, completed by his son Pierre in 1949, owned a majority of the château. The 1945 Château Margaux has held up well but is surpassed by other wines this vintage and personally, I have fonder recollections of the 1947. Bottles should be consumed in the near future. Completing the line-up, the 1928 Château Margaux, was born in one of the most fêted vintages of the century, notorious for its masculine wines that took years to come round. This is a wine that I have not encountered previously and dates back to a period where the First Growth was under the proprietorship of a syndicate headed by Pierre Moreau. Mavens such as Michael Broadbent MW have regaled this wine and its formidable reputation was testified by this almost stocky, masculine, Pauillac-like Margaux that shrugged off its age and frankly, showed up the 1945. In a word - immense.

Château Lafite-Rothschild

Next is the so-called “First of the Firsts” since it headed the original 1855 classification: Lafite-Rothschild. Lafite-Rothschild is the most nuanced of the First Growths, rarely a wine of fireworks, but one of grace, elegance and sublimity.

The 1986 Lafite-Rothschild has garnered a strong reputation though personally I have never considered it to be a perfect wine. I will not dwell too long as a slightly better ex-château example will be included in a forthcoming vertical. It is typically masculine and structured like many 1986s, though it did respond to decanting then aeration in the glass, mellowing after a couple of hours. If you do not mind, I will skip the 1966 Lafite-Rothschild because it is the only bottle that falls short of expectations and I was fortunate to encounter the same wine from a pristine bottle just three weeks earlier – part of the forthcoming Lafite-Rothschild retrospective.

The 1959 Lafite-Rothschild has long had the upper hand over the 1961. It is the vintage that succoured the rivalry between Lafite and Mouton, between cousins Baron Guy de Rothschild (co-owner of Lafite with Baron Elie de Rothschild) and Baron Philippe de Rothschild at Mouton-Rothschild. Baron Philippe had written to Daniel Lawton to advise avoiding gamesmanship to extract a higher price over the other as a mark of supposed superiority. In a fascinating exchange of letters, he accused his cousin of stalling until after he had released the 1959 Mouton-Rothschild, only for the 1959 Lafite-Rothschild to be released at 15% higher! Elie de Rothschild rebuffed any bad sportsmanship and wrote to Baron Philippe: “I have always sold wine without worrying about anyone else...” It was a family feud that simmered until the 1970s. So what about the wine? Again, you will see another note in the forthcoming vertical but both attest a stupendous 1959 Lafite-Rothschild, perhaps more conservative than its peers, yet pure and bewitchingly nuanced. The best example I have encountered is an ex-château magnum but both bottles suggest the 1959 continues to give pleasure from bottle.

To put the 1959 into context, ladies and gentleman, behold the 1953 Lafite-Rothschild! Following three previous bottles over the years that were in chronological order “corked”, “corked” and “probably stored next to a kitchen over for most of its life”, the 1953 finally did what I always expected...

It blew my mind. It was one of the highlights of a memorable evening - an absolute pearl, redefining my expectations of Lafite-Rothschild because with the exception of the 1870, it occupies an altogether different realm to practically every other vintage I have encountered. I will leave my tasting note to describe the wine but I will declare that amongst the pantheon of great 20th century Claret, the 1953 Lafite-Rothschild stands at the pinnacle.

The final vintage was the 1945 Lafite-Rothschild. This was an excellent bottle but if you don’t mind, I will deify another bottle encountered in Hong Kong that represents the finest example I have ever encountered.

Château Latour

Moving from the northern limit of Pauillac to the southern, Château Latour is the most aristocratic of the First Growths, more structured than Lafite-Rothschild and less flamboyant than Mouton-Rothschild. It is the quintessential Pauillac and perhaps the quintessential Bordeaux.

How many times will a 1961 Latour be poured and it is fighting for the limelight? This is embarrassing, but it is the fourth bottle I had drunk in almost as many months. Over numerous encounters it flirts with perfection and this “flirts” rather than “achieves” simply because the prior bottle that I had encountered in Hong Kong had that extra level of precision. It is still as regal and blue-blooded, as damn impressive as it always shows, just not perfection on this occasion. The 1959 Latour is a wine that I have less experience with compared to the 1961. It is always a more carefree, sumptuous, decadent wine than the 1961 thanks to a blisteringly hot July and August and an Indian summer the produced concentrated musts. According to château records, the 1959 endured a “tumultuous fermentation” because vat temperatures were difficult to control. Perhaps in recent years it has just slipped down a notch, lost a bit of lustre compared to say, the Lafite-Rothschild, and yet it still to this day almost overwhelms the senses with its precocity and charm. The 1949 Latour is a particular favourite of mine. The château records describe it as a year of "climatic accidents": an exceptionally dry season with drought that caused hydric stress and a very small crop, the juice so concentrated that it was difficult to vinify in these pre-temperature controlled times. Nevertheless, as the proprietor Comte René de Beaumont wrote in his annual statement, the 1949 reawakened interest amongst the Bordeaux trade that had been in the doldrums after the war. It has almost been one of the most refined and elegant Latour wines, perhaps the one that nods to Lafite-Rothschild in terms of its transparency and tannic structure. Classic Claret in every sense, it boasts a symmetry and poise that has been rarely captured again, here the growing season dictating the style as much as the terroir.

Last but not least, the 1929 Latour. Wow. Having tasted around sixty vintages of Latour to date, this ranks amongst the very greatest. This was one of the final vintages overseen by Daniel Jouet, the régisseur who presided over 48 vintages between 1883 and 1932. A total of 62 tonneaux were originally produced and interestingly, its en primeur price was actually less than the previous three vintages. Given the euphoric praise that Broadbent confers upon the 1928, I presupposed that the 1929 would be shaded by that “Everest of a wine” to quote the great man. Well, that might not be the case now. In fact, on my last visit to the château I broached Frédéric Engerer on the subject. I enquired whether I was showing temerity suggesting that the 1929 Latour is better than the 1928? He immediately concurred and seemed as enraptured by the 1929 as myself. (Incidentally, for those that follow my notes and never spotted one for the 1928 Latour, don’t worry, it’s coming up in the Latour vertical. In magnum.)

Château Mouton-Rothschild

We finished with the odd-man out, the First Growth only since 1973 since it was unfortunately suffering some malaise in the run-up to the 1855 classification and was overlooked. Mouton-Rothschild is the “pop star” of the First Growths, renowned for its artist labels that in some periods over-shadowed the contents inside. It is generally the most flamboyant and richest of the First Growths though that has changed under Philippe Dhalluin in recent years as it has harnessed more sophistication and nobility. The 1982 Mouton-Rothschild is variable. I have enjoyed astonishing bottles and magnums that deserve perfect scores and the adulation from the likes of Parker that did a great deal to enhance its reputation after a rather rum period during the 1960s and 1970s. Unlike the 1982 Latour, it is not a predictable wine. Sometimes it comes across as rather ostentatious and unrefined, a First Growth showing off, and First Growths never need to do that.

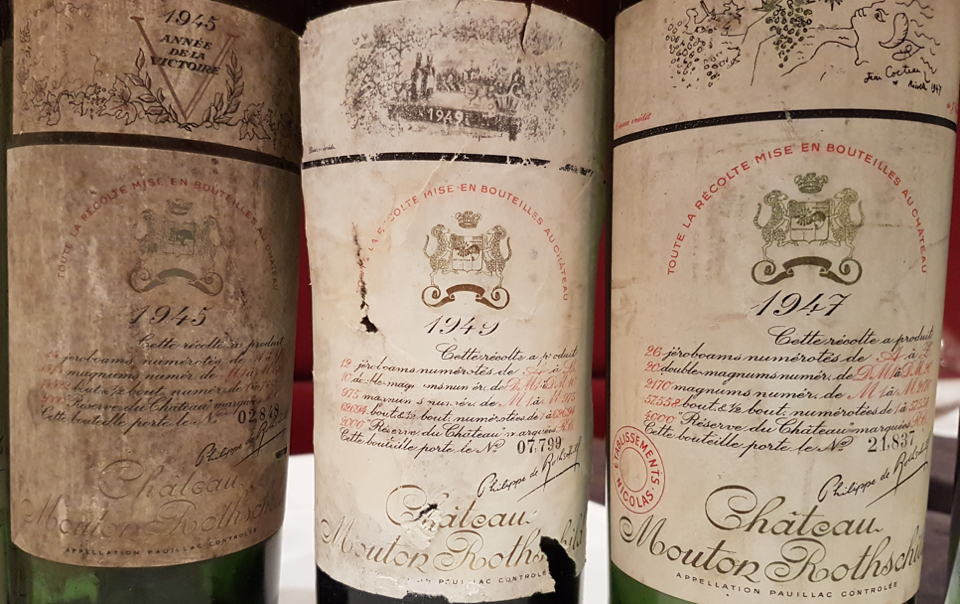

I finished this journey with the greatest trio of wines from a single château that I have ever imbibed: 1945, 1947 and 1949 Mouton-Rothschild. When I saw wine writers sprinkling perfect scores here, there and everywhere, I would have liked them just to sit down and taste these three wines so that they may experience genuine perfection. Perfection is the 1945 Mouton-Rothschild, the famous victory year, an emblem that France was still France after German occupation insofar that it could rebound from the war and immediately produce immortal, extraordinary wine that decades later, continue to dumbfound and amaze. Here is an example of a wine that defies logic and rules...that extraordinary eucalyptus/mint scent on the nose. Where does that come from? The lasciviousness of the palate, the velvety texture, purity and intensity undimmed after so long. How is it possible? This is a virtual repeat of the only other bottle that I encountered a decade ago. Omar mentioned that he paid through the nose to guarantee provenance and it clearly shows on this sui generis that has entranced so many over the years.

Then the 1947 Mouton-Rothschild... Again, this defies all expectations because this vintage produced an array of rich, decadent, fruit-driven wines that to be honest, have not lasted quite as well as either the 1945 or 1949. Yet this 1947 is cool, calm and collected, brilliantly poised, exuding those Pauillac leitmotifs of graphite and tobacco, pixelated to the n’th degree on the finish. It is easily the best Left Bank 1947 that I have encountered. In any other circumstance I might have been tempted to give it a perfect score. Finally the 1949 Mouton-Rothschild. Here is a nugget of information for those who dismiss wines of low alcohol. I was recently perusing an interview that I conducted with Michael Broadbent back in 2004 in which I asked that old chestnut: What is your most memorable wine? This man could choose just about anything from the 19th and 20th centuries. "The 1949 Mouton-Rothschild," he replied unhesitatingly in his headmaster-like tone. "Did you know something? Baron Philippe once told me that it was just 11.3° alcohol. Imagine that!" Almost seven decades later, the 1949 Mouton-Rothschild is an otherworldly, life-affirming, jaw-dropping masterclass in mature Claret. Just a suggestion of menthol on the nose, though not close to the degree displayed on the 1945, filigreed tannin, an unbridled sense of tension and mineralité - it is utter perfection. In some ways, you could argue that its typicité renders it an even greater expression of Bordeaux than the more outrageous 1945 but I will not enter that contentious argument. I’m just privileged to have beholden both.

Is that enough? Are you sick of reading this article yet? I would be. Hopefully I can offer some vicarious enjoyment and context, but no more. If I mention that one Sauternes finishes the evening and it happens to be 1945 d’Yquem, is that just too much? Maybe.

Final Thoughts

So let’s wrap this up. This was one of the most memorable vinous evenings of my life. It confirmed that the First Growths deserve their reputation as “the best” whilst also evidencing that the 1855 classification has its imperfections, the original omission of Mouton-Rothschild being the most glaring. The 1945, 1947 and 1949 are all technically Second Growths. No wonder Baron Philippe was a bit miffed.

This evening could have been disastrous because the stakes were so high, lofty expectations that surely cannot be met. But as I mentioned, these bottles surpassed everyone’s wildest expectations. People were just speechless by the end. Kudos to Omar Khan who spent many months sourcing the bottles and checking provenance - it paid dividends on the night. As I reminded attendees, we had witnessed an evening that might never happen again since you could reassemble all those bottles and vintages and the odds of matching the quality throughout the evening are very slim.

Catching my train home from Waterloo, I must admit that I was still pinching myself. Did that really happen? I can remember when I started in the wine trade, wondering if I would ever drink a First Growth. I would not have believed you if you had told me back then that I would drink such wines in one sitting. Was it too much? Not in my opinion. It was sufficient number to enjoy the wines but crucially, a unique chance to contrast them side-by-side, an expensive but always illuminating experience that I am grateful for.

I had climbed up to the very summit of wine. The view was amazing.

(My sincere thanks to Omar Khan at “International Wine & Business” who outdid himself on this evening and also to the team of sommeliers and chefs at the Park Lane Four Seasons.)

You Might Also Enjoy

Last Man Standing: Bel-Air Marquis d’Aligre, Neal Martin, May 2018

A Century of Bordeaux: The Eights, Neal Martin, May 2018

Purple Reign: La Conseillante 1966-2015, Neal Martin, May 2018

The F-Word: Bordeaux 2017, Neal Martin, April 2018

A Beautiful Stay: Beau-Séjour Bécot 1970-2015, Neal Martin, April 2018

Life Is Funny Like That: 1999 & 2015 DRC, Neal Martin, April 2018

Mother & Child: La Lagune 1962 – 2015, Neal Martin, April 2018