Browse using the new Vinous website now. Launch →

Printed by, and for the sole use of . All rights reserved © 2015 Vinous Media

Outsider Looking In: Sociando-Mallet 1982-2015

BY NEAL MARTIN | MARCH 6, 2019

Bordeaux is built around an immutable hierarchy set in stone in 1855. As the ink dried on the classification, I suspect nobody believed it would still shape the region into the 21st century and beyond – and arguably more so now than ever before. Whether you agree with the classification or not, it inevitably creates winners and losers. Properties with exceptional terroir that underperformed at the time of assessment (the decade before 1855) pay the price in perpetuity. There are mundane reasons for exclusion. A négociant once told me that had Sociando-Mallet been located less north and, let’s say, closer to Calon-Ségur, then doubtless it would have been classified, given its enviable gravel soils and proximity to the Gironde. Unfortunately, Sociando-Mallet lay beyond the geographic purview of those assigned to gather data, and over subsequent decades this injustice left the estate reeling, to the point where it started crumbling into oblivion. Thankfully, one man saw its potential and single-handedly drove the regeneration that led to its current status as potentially the best non-classified growth on the Left Bank. I had not visited for several years, so I arranged to reacquaint myself with Sociando-Mallet and discover how vintages over the last four decades have matured.

History

The history of Sociando-Mallet can be traced back to March 17, 1633, the date of a document referring to Saint-Seurin-de-Cadourne, a propitious terre noble that belonged to a Basque nobleman named Sièvre Sociando. The estate passed through the hands of several owners until around 1850, when it was sold to a naval captain named Mallet. Hitherto the wine from this terre noble had been known as Lamothe, but Mallet renamed it Sociando and appended his family name. In the early 1870s, as recorded by the 1874 edition of Féret, Mallet’s widow sold the property to the Alaret family, who presided over the increasingly esteemed wine. The 1898 edition of Féret places it second behind Château Verdignan on their list of best Cru Bourgeois in Saint-Seurin-de-Cadourne. At that time, the proprietor was Léon Simon, who had bought the estate in 1878. Production was still comparatively small, at 45 tonneaux per annum. During the 20th century, the estate had a succession of owners that included the négociant Delor; Louis Roulet, in the 1940s and 1950s; and a former mayor of Saint-Seurin.

The lack of continuity in ownership hindered long-term investment, and Sociando-Mallet began treading water. Quality went off the boil, and the château building began to fall into disrepair. The wines’ reputation was nothing like its halcyon days at the end of the 19th century, even though it was included in the inaugural Cru Bourgeois classification of 1932. The estate finally found itself under the proprietorship of the Téreygéol family. I have read that François Téreygéol bought the property, although I believe it would have been his father Emile. But that is all by the by, because the Téreygéols decided to focus on their other property, Pontoise-Cabarrus, and put Sociando-Mallet on the market. Both were in dire need of investment and the family could not finance both. In 1969 a buyer was found. His name was Jean Gautreau.

Gautreau, born in 1927, had been employed as a salesman for the négociant arm of the Miailhe family and was escorting a Belgian client around the northern Médoc when he chanced upon Sociando-Mallet. According to Clive Coates, writing in his Grand Vin tome, Gautreau bought the estate for 250,000 Francs because he admired the vista across the yawning Gironde estuary. Some say he initially saw it as a mere holiday home, and only after encouragement from Jean-Paul Gardère at Latour and Jean-Michel Cazes at Lynch-Bages did he realize its potential as something more. At that time he had no practical experience of winemaking. The vineyard had withered to just five hectares and the buildings were in ruinous condition, without a cellar to speak of. However, as Gardère and Cazes explained to its new owner, the estate occupied a propitious gravel croupe, basically an extension of Montrose to the south. So Gautreau spent years restoring Sociando-Mallet with the ultimate aim of creating a vin de garde. By 1982 he had reconstituted the vineyard and brought it up to 30 hectares, installed temperature-controlled stainless steel and concrete vats, and made the château inhabitable. Part of the reason he was able to finance the reconstruction of Sociando-Mallet was that he continued to run his own independent merchant, through which he distributed the wine. Gautreau constructed a large balcony overlooking the vineyard and the estuary over to Blaye and beyond, to admire the view that had sparked his interest.

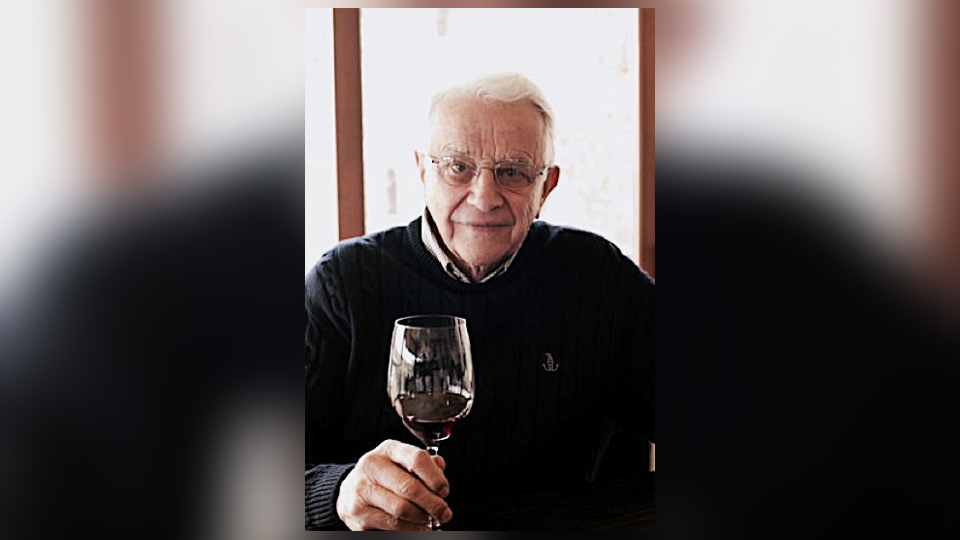

Jean Gautreau as seen when I visited the property in 2006.

I used to meet Jean Gautreau during en primeur visits, though I have not seen him for a few years now. He always welcomed me with open arms, often in sunglasses for some reason, happy that at least one writer had bothered to visit a château disadvantaged by its location far from itineraries of Grand Cru Classé. His pride in Sociando-Mallet was tangible and infectious. One could misinterpret his passion for arrogance, given that Sociando-Mallet was unclassified. Hubristically in some eyes, he refused to submit his wine for the Cru Bourgeois reclassification of 2003, when it surely would have become the tenth Cru Bourgeois Exceptionnel, and instantly torpedoed some of the classification’s credibility. This can be excused because of Gautreau’s unstinting dedication to what was an unfashionable location; because he turned a run-down estate into one of the best in the northern Médoc; and not least because of the quality of the wines. Now in his 90s, Gautreau lives in the town of birth of Lesparre, enjoying a well-deserved retirement. It was a pleasure to meet his daughter Sophie Gautreau, who currently runs the estate.

Sophie Gautreau, daughter of Jean Gautreau, has taken the reins from her father.

The Vineyard

Considering that the vines once occupied just five hectares, it is impressive that there are now 77 hectares in production. The current vineyard comprises 55% Cabernet Sauvignon, 40% Merlot and 5% Cabernet Franc, though in the past there was up to 5% Petit Verdot. The main plot is around the château, and there is a second 28-hectare parcel toward the village of St-Seurin-de-Cadourne, used for the second wine. The vines average 40 years of age and are pruned double Guyot and planted at around 8,333 vines per hectare. There is no de-leafing or green harvest as at many other properties; Gautreau vehemently disapproved of those practices and preferred to sort the bunches in the cellar, notwithstanding that their exposed vineyard needs protection by the canopy from the wind and sun. Ergo, the yields at Sociando-Mallet tend to be higher than those of its peers, often around 50hl/ha. It can be argued that this modus operandi imparts a greenness that can affect the wine in its youth. I will broach that later.

Looking over the main vineyard at Sociando-Mallet from the balcony, the banks of the estuary around 800 meters away. You might be able to make out the eyesore that is the nuclear power station on the opposite bank.

During the harvest, head winemaker Pascale Thiel and Sophie Gautreau enter the vineyard to choose which plots to pick, approached parcel by parcel using two teams of around 140 vendangeurs. “We spend all afternoon in the vineyard choosing the plot. We use two sorting tables before de-stemming, and then a vibrating sorting table,” Sophie Gautreau informed me as we chatted on the balcony. Harvest had begun, and in the distance, pickers worked through the vines. “We ferment the wine in cement and stainless steel vats (usually with a long cuvaison of between 20 and 35 days), maturing for 12 months in barrel before racking.” A high percentage of new oak is used here, at least 80% but often closer to 100%. Just over 30,000 cases are produced of the Grand Vin plus a second label, previously called Latigue de Brochon but now simply Les Demoiselles de Sociando-Mallet, that sees a modest 25% new oak.

I also undertook a complete vertical of the elusive Cuvée Jean Gautreau from the debut 1995 vintage. The first I heard about this cuvée was about a decade ago when I was invited to a vertical tasting in London. It has remained an insiders’ secret, perchance because it was intended as a one-off for private use. In fact, it has been produced every year since, and a few cases dribble out as late releases. The Cuvée Jean Gautreau is a specific barrel selection made in the winery, where some 80 barrels, matured in 100% new oak, are whittled down to just three of the best barrels, or approximately 900 bottles. Sophie Gautreau told me that initially the cooperage was only Seguin Moreau, although since 2000 they have used a mixture.

The Wines

One of my regrets is not being able to attend a complete vertical tasting of Sociando-Mallet a few years ago to celebrate 40 years since Jean Gautreau’s acquisition of the estate. I was eager to make amends and tasted most major vintages from 1982. In addition, I had the opportunity to taste a complete vertical of the Cuvée Jean Gautreau from the debut 1995 to the present.

This tasting proved that Sociando-Mallet has a strong case that it is a classed growth in all but name. One of its disadvantages is that it unequivocally requires bottle age – let’s give a ballpark figure of 10 years in a good vintage. It is true that there can be green traits in its youth, but these tend to ebb away as the wine matures, perhaps similar to the way some whole-bunch Pinot Noirs subsume stemminess that can transmute into attractive secondary characteristics. Sociando-Mallet vintages from the 1980s attest to a wine with inbuilt longevity that must surely derive from its gravel soils. The oldest vintage, the 1982 Sociando-Mallet, is still going strong and indeed, a few months earlier it had easily held its own among far more expensive Grand Cru Classé at a 1982 horizontal. The 1983 Sociando-Mallet has not fared as well; however, the 1985 and 1986 Sociando-Mallet continue to give drinking pleasure and reflect the character of those vintages, the former fleshy and polished, the latter fresh, ferrous and structured. I often find that Sociando-Mallet excels in a warm growing season, and the 1990 Sociando-Mallet proves that to be the case. It’s a gorgeous wine that is spicier than previous vintages, revealing a hint of curry leaf on the finish, and clearly à point.

In the mid-1990s we see a slight change as the wine is entirely raised in new oak. I am not completely sold on this approach. The aromatics on the 1996 Sociando-Mallet are rather dictated by the cooperage, unlike the slightly superior 1995. In a less ripe vintage such as in 1998, I find the new oak disproportionate to fruit that cannot quite give it the necessary support, perhaps one key difference between Sociando-Mallet and the First Growths that share similar terroir. The 2000 Sociando-Mallet was not shown at the vertical and has always been a controversial wine. I remember being impressed during en primeur, and yet subsequent encounters have revealed a nagging greenness that leaves a bitter/vegetal note on the finish. I dug out another bottle from my cellar, but it too was disappointing compared to other vintages. Perhaps this is one year when some green harvesting or de-leafing would have benefited the wine. Far superior is the 2001 Sociando-Mallet, which is more harmonious and fresher, showing no trace of underripeness. The 2003 vintage favored the northern Médoc and especially Saint-Estèphe, and while you can shell out for the touted Montrose and Cos d’Estournel, the best value for money might be the outstanding Sociando-Mallet. In this season, Jean Gautreau’s eschewing of effeuillage was advantageous; others cut back canopies and left exposed bunches to be grilled by the merciless heat that summer. Even better, perhaps, is the benchmark 2005 Sociando-Mallet, where everything comes together, sporting fine-boned tannins that are not always associated with this cru. This is the first vintage where I feel more bottle age will not go amiss. I must admit to finding the 2007 and 2008 Sociando-Mallet a little disappointing and too herbaceous for my liking. This is put into sharp relief by the outstanding 2010 Sociando-Mallet, destined to be one of the most structured and longest-lasting of all vintages produced to date. Readers can find more recent vintages already entered on the Vinous database from previous tastings.

Not on the database, at least until now, are notes for the Cuvée Jean Gautreau. Because of the way the barrels are selected, the blend can differ greatly. Readers will find details of all the assemblages within the tasting notes, but to give one example, the 1997 comprises 60% Cabernet Sauvignon while the 1998 includes 90%. That said, the wine is an expression of Gautreau’s predilection instead of an articulation of a specific plot of land; therefore, despite varying blends, there is a sense of stylistic consistency. Though rarely seen, prices are little different from Sociando-Mallet itself, partly because few people are aware of the Cuvée Jean Gautreau’s existence and partly because it is not implicitly superior. There are some excellent vintages, such as the 2001, 2009 and 2010 Cuvée Jean Gautreau, but they are as much a reflection of those great growing seasons as anything else. Stylistically, they would appeal to palates that prefer a modern style of Left Bank, richer and glossier than the regular Sociando-Mallet. At its best, the Cuvée Jean Gautreau can certainly mature over 15 to 20 years; in other vintages, especially those that experience weaker growing seasons, it seems burdened by the new oak and the results are less interesting.

Final Thoughts

We often talk about proprietors who have followed their own path. Few in Bordeaux personify this more than Jean Gautreau. Sociando-Mallet struck out on its own from the moment Gautreau acquired the property and commenced rebuilding it. Now it seems to occupy a no-man’s land. Received wisdom is that it ranks above Cru Bourgeois, a view shared by me and reflected in its higher market prices, yet it is destined never to be part of the “club of 1855.” It is an outsider looking in. There is no question that it occupies great terroir, but Sociando-Mallet has always had obstacles in its way: its distance from the city of Bordeaux; its high turnover of owners in the 20th century and concomitant decay; its omission from the 1855 classification and (voluntarily) as a Cru Bourgeois Exceptionnel in 2003. Furthermore, it has never been the most consistent of wines. Vintages like 2000 reinforce a sense of unpredictability, compounded by youthful greenness, which was anathema at a time when the vogue was for low yields and ripeness. Sociando-Mallet would have become an anachronism had the wines not cut the mustard.

Ultimately, the estate’s doggedness under Gautreau is its strength. Even without Jean Gautreau at the helm, Sociando-Mallet will always be blessed by the gravel croupe that elevates its wine above that of its peers, putting it neck and neck with Grand Cru Classé. One can argue that its site is even more advantageous thanks to the regulating affects of the Gironde estuary, which is wider here and thus more influential than farther south in Saint-Julien or Margaux. At least now there are one or two others in the area with the same vision and conviction, notably Jean Guyon at Haut-Condissas and Rollan de By farther north (see Aiming High: Haut-Condissas 1997–2015 for last year’s article on Vinous). For the imminent future, I see Sociando-Mallet continuing just as it has done over the last few years, punching above its weight, official status be damned.

See the Wines from Youngest to Oldest

You Might Also Enjoy

Looking The Part: Pichon-Baron 1953 – 2015, Neal Martin, January 2019

The DBs: Bordeaux 2016 In Bottle, Neal Martin, January 2019

Long Distance Runner: Brane-Cantenac 1924-2015, Neal Martin, January 2019

Enigma Variations: Lafleur 1955-2015, Neal Martin, November 2018