Browse using the new Vinous website now. Launch →

Printed by, and for the sole use of . All rights reserved © 2015 Vinous Media

The Margaux Paragon: Rauzan-Ségla 1900-2015

BY NEAL MARTIN | APRIL 16, 2019

Terroir. Terroir. Terroir.

Terroir. Terroir. Terroir…

That’s all you hear. It’s all about terroir.

Another statement in vogue amongst winemaker brethren is: “I’m not a winemaker.”

My heart always sinks a little when I hear this.

Take the most impeccable terroir imaginable. Without man turning fruit into wine, all it will bestow is bird food and rotting grapes. Imploring that you are not a winemaker when your job is to make wine is surely an abdication of responsibility, an abnegation of a noble vocation since time immemorial. Based on my own experience, I would rather drink a wine made by a passionate, talented, quality-focused winemaker dealing with average terroir than an indifferent, lackadaisical winemaker from outstanding terroir. Which brings me to Rauzan-Ségla – a case example of the critical importance of the winemaker.

Rauzan-Ségla is blessed with some of the finest terroir in Bordeaux. This is a constant; it does not and will not change, and you’ll learn all about it in this article. However, from 1661 to the present day, the story of Rauzan-Ségla has been determined by the dedication and skill of the people who call the shots. Here we will meet some of those people: Pierre de Rauzan, Jean de Rauzan, Anne-Marie de Briet, Catherine Jacquette Clémentine, Eugène Durand-Dassier, John Kolasa and Nicolas Audebert. Through the ages, they have one goal in common: To create the best wine possible. But we will also meet others with different priorities who ran roughshod over this prime terroir, the consequences tangible in the wines.

For some reason there is always a cloudless blue sky whenever I visit Rauzan-Ségla.

This is a château retrospective that I have been itching to do for many years. Rauzan-Ségla was one of my ports of call on my first trip to Bordeaux, and I have visited countless times. I conducted one vertical tasting in Paris several years ago, but upon joining Vinous, I resolved to undertake another retrospective and author a comprehensive article that not only appraises multiple vintages, but tries to get under the skin of this important Grand Cru Classé.

Early History (1661-1899)

Rauzan-Ségla’s genesis as part of the Gassies estate played a crucial role in the evolution of viticulture in the Médoc. I have delved deep into its history, gleaning details from the monograph given to me by former estate manager John Kolasa many years ago, entitled “Château Rauzan-Ségla: La naissance d’un grand cru classé.” Like many similar texts, it burgeons with minutiae, though it was clearly edited during a coffee break, since it’s a jumble of information. Translating the complex French prose and reordering the meandering chronology took many hours. Hopefully it was worth it in the end.

There are no prizes for guessing that Rauzan-Gassies and Rauzan-Ségla are consanguineous. In medieval times, the land was part of a maison noble called Gassies, within the seignerie de Margaux. In the 16th century, the écuyer or squire was Gaillard de Tardes; in 1615 it was Bernard de Faverolles, who lived in the parish of Margaux. According to the monograph, Pierre Desmezures de Rauzan rented out properties to produce their respective wines, ostensibly multiple fermages that included no less than Latour (1679 to 1692/93) and Château Margaux (1658 to 1663). He gained intimate knowledge of the land and in many ways incepted the notion of terroir. On September 7, 1661, he himself became a landowner, acquiring Gassies and land in Pauillac that eventually begat Pichon-Baron and Pichon-Lalande. Unfortunately, there are no records of the boundaries of Gassies, though it must have been extensive, since surviving documents show that the sum paid was 2,641 livres. Pierre Desmezures de Rauzan died in 1692, and his widow, Jeanne de Moncourier, passed away eight years later. There followed a rather convoluted series of litigations between his 11 children, for – unusually in this age of high infant mortality – all his offspring lived into adulthood. In April 1700 his daughter Thérèse became the owner of vines in Pauillac upon marriage, whilst Simon-Jude de Rauzan inherited the vines in Margaux. Deeds of sale indicate that Gassies comprised some 65 parcels and some 234 presses, suggesting that the estate was assembled via piecemeal purchases over many years; this is supported by the monograph, which details numerous acquisitions between 1705 and 1747. In 1728, Simon-Jude bequeathed the land to his sons Jean-Baptiste (known as simply “Jean”) and Simon de Rauzan.

By now the Rauzan family was firmly installed as aristocrats and parliamentarians, and their wine earned a reputation befitting a noble family. Jean de Rauzan expanded the château building by adding an extra wing and cultivating its gardens. Bernard Ginestet, in his book Margaux, recounts a wonderful vignette, describing how de Rauzan sailed to London in order to auction his wine from a boat moored in the Thames. His ploy failed to drum up interest, so he ordered his crewmen to throw one barrel into the turbid, putrid waters of the river, prissily declaring that he would rather throw it away than sell it cheaply. Onlookers looked on, bemused. So he ordered the crew to throw in a second, then a third and a fourth barrel. Aghast at seeing precious wine go to waste, buyers finally began bidding. You might argue that today’s en primeur follows similar lines.

Around this time, the estate was divided to form Rauzan-Ségla and Rauzan-Gassies, but the details of the division are sketchy. The two estates were split up and reunited over decades, like young lovers bickering and then reconciling, and therefore it is difficult to pinpoint a year of separation. A letter from the future proprietor Comte de Castelpers, dated 1844, states that the division transpired more than a century earlier. My own deduction is that Jean de Rauzan’s widow, Magdeleine Roullier, began a dispute with her relatives that lasted for 30 years. The monograph states that from the 1730s, “Domaine Roulliers” and Rauzan began to dissociate themselves, though it was only after 36 years of litigation that they became separate legal entities. Later on, sections of Rauzan were cleaved away as parts of dowries to form Desmirail and then Marquis de Terme.

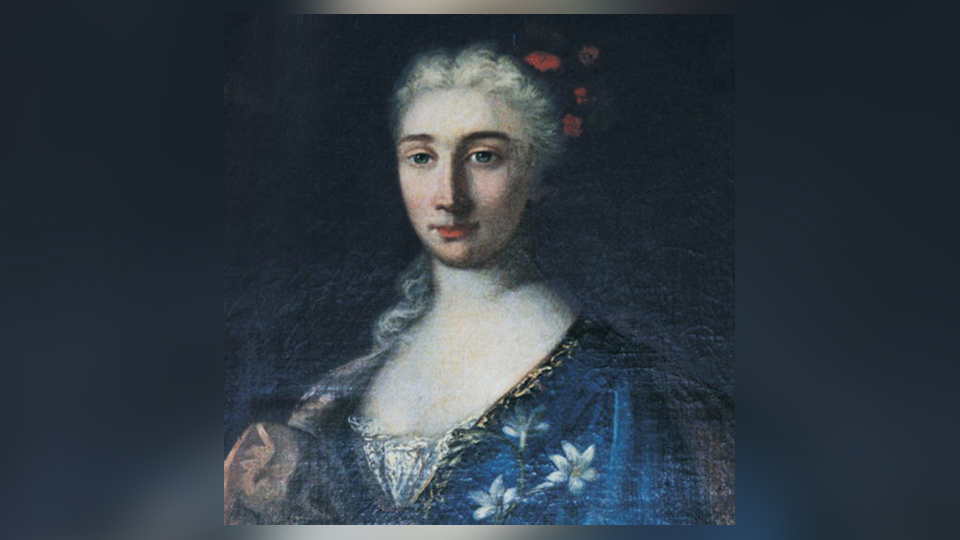

Marie-Anne de Briet, who lived from 1736 to 1816.

For a number of decades, Rauzan-Ségla was managed or passed through the hands of the female members of the family. When Jean-Baptiste (Jean) de Rauzan died on August 1, 1780, his son-in-law Philippe Simon de Rauzan inherited the land, though in reality it was Marie-Anne de Briet, his wife since 1760, who became the “mistress” of Gassies. She ran its affairs from her rented apartment in Rue du Hâ in Bordeaux, traveling up to the estate to oversee the harvest and even becoming an unofficial spokesperson for the Second Growths in terms of pricing their wines vis-à-vis First Growths long before the 1855 classification. It was she and not her husband who engaged in an exchange of letters with Thomas Jefferson, both a fan and a client of the wine. It seems clear that de Briet had plenty of gumption, and though in fact divorced from her husband, she seems to have maintained control. A stone plaque commemorates both her tenure as “La Baronne de Ségla” and her love of growing hydrangeas.

Rauzan-Ségla stone

plaque.

The elder of Jean de Rauzan and Marie-Anne de Briet’s two daughters, Catherine Jacquette Clémentine, married Baron Pierre-Louis de Ségla on August 10, 1785. This was an important union, since her husband appended his name to the cru. Alas, just four years later, he died from a gunshot whilst standing at a library window at his family estate, Château Monbardon. His young widow decided to remain at Monbardon to raise her three daughters. The youngest daughter became Madame Descages when she married the proprietor of La Louvière, whilst the middle daughter married Louis Jean Marie de Castelpers and continued to run Rauzan-Ségla with her mother. In terms of pricing their wine, they pegged their price against the First Growths, or at least tried to. Poitevin, régisseur at Latour, wrote: “Madame de Rauzan at Margaux, whose wines, being the first of the Second Growths, are much sought after and esteemed, sold her 1803 and 1804 crops nearly two months ago at 600 francs per tonneau, though she always differed by only 200 or 300 francs from Latour.” However, Latour had sold for 1,200 francs, so they were a bit short in that respect.

Baron Pierre-Louis de Ségla painted in his infantry uniform.

When Marie-Anne de Briet passed away in 1816, ownership passed to Catherine and her sister, although they would only stay at the property during harvest. Meticulous records of stocks were maintained during this period, and it’s fascinating to see how they stocked barrels of aged wine up to 10 years old. Catherine became the sole proprietor in July 1826 when her sister passed away, and since none of her three daughters wished to join their aunt as co-proprietor, Catherine bought their 50% share for Fr 275,000. Henceforth, management passed to her husband. He embarked upon a reorganization of the estate and began by accusing the cellarmaster of dishonesty and having him swiftly replaced. The Baron de Castelpers was adamant that Rauzan-Ségla should fetch the highest price on the market, though documentation suggests that he was motivated not simply by pride in his wine but also by his desire to sell the estate at a considerable profit.

As it turned out, that sale took longer than he expected. His wife, the last of the de Rauzan lineage, passed away on July 11, 1847. From 1847 until 1866, the proprietorship of Rauzan-Ségla was divided: half apportioned to Baron de Castelpers and his son-in-law, Baron d’Adeler, and half shared among Catherine’s grandchildren. This period of dual ownership includes the 1855 classification when, thanks to the historical efforts of Marie-Anne and the Baron de Ségla, it was classified a Second Growth. Not only that, but Rauzan-Ségla was listed second only to Mouton-Rothschild, which theoretically puts it at the top of the list since Mouton’s promotion. Despite this accolade, the estate remained for sale, the vendors doubtless pessimistic about the viability of winemaking in the Médoc due to the ongoing oidium crisis.

In February 1866, the 34.25-hectare estate was sold to pastor of the reformed church and financier Eugène Durand-Dassier for Fr 730,000. Was he the real purchaser? Documents reveal that in fact the funds came from his wife, Julia-Augusta Dassier. Presumably in that misogynistic era, the owner of a prestigious classed growth ought to be male. Whoever was in charge, they would have to contend with phylloxera, which came knocking on their door on November 17, 1879, when the pernicious louse was first reported by régisseur Etienne Legras. As at many estates, their immediate recourse was to inject the ground with carbon sulfur. It could not cure phylloxera, though it kept it at bay and saved their sacred French rootstock... for a time. As I shall explain in my outline of the composition of the vineyard in 1900, they embarked upon a reluctant, piecemeal adoption of resistant American rootstock. In any case, what is often forgotten is that at the time, the more impactful problem was not the “slow creep” of phylloxera but mildew, which ravaged the vines between 1882 and 1892, so that in many years only around half the average volume of wine was produced.

Despite the twin specters of phylloxera and mildew, the late 19th century was seen as a golden age for the estate, their wines highly esteemed vis-à-vis those of their peers. Is it because they were relatively proactive in combating the encroaching diseases? I have never tasted any bottles from this century, so I must enjoy them vicariously. Editions of the Féret guide from 1878 and 1893 rank Rauzan-Ségla as second in Margaux, with Rauzan-Gassies one place behind. Here I will stop the clock, since 1900 coincides with the oldest bottle served at the vertical, and continue the history in tandem with the wines, after we examine the vineyard and current practices.

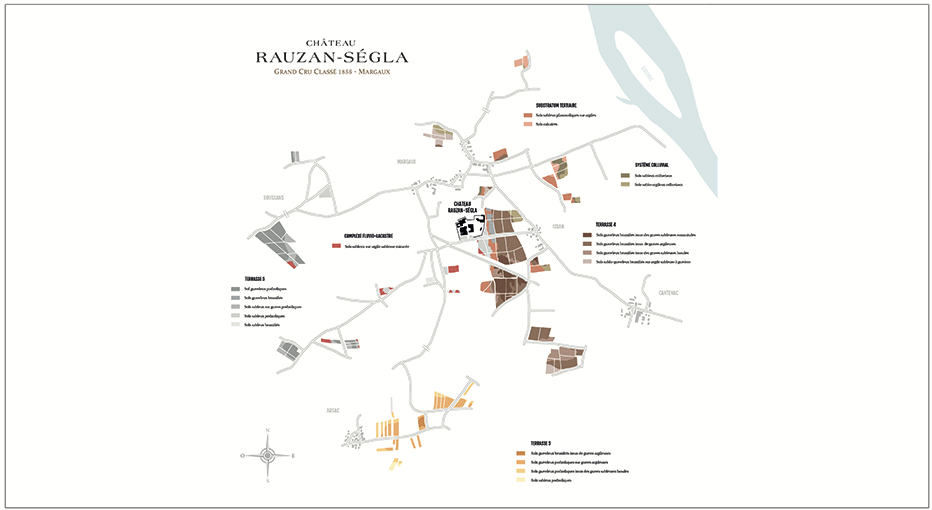

Vineyard

The estate covers 74.9 hectares in total, planted with 72 hectares of vine, of which 70 hectares are in production. This includes eight hectares bought in the commune of d’Arsac in 2008 and a further eight hectares from a lieu-dit known as Boston two years later. What you might call the heart of the vineyard lies east and southeast of the château, on the other side of the D2 road from d’Issan. There are three distinct parts to the vineyard, which lies on glacial alluvial terraces, mainly gravel, sand and large stone from the Pyrenees, that are referred to in ascending numerical order from one to six as you travel southwest to northeast. Margaux is the only Bordeaux appellation to occupy all six terraces, and Rauzan-Ségla is home to three. First, there is a large gravel terrace (Terrace 4) that runs parallel to the estuary and rises 18–20 meters. This is where around 30 hectares of Pierre de Rauzan’s original estate were located; today the vines are mainly Cabernet Sauvignon, although some Merlot is also planted. The second part is composed of clay-limestone soils that include blue, grey, brown and red clay, which are said to give the wine its freshness, and is planted with more Merlot. The third part consists of fine gravel and sand (Terrace 3 and 5), courtesy of parcels acquired from de Labourgade and Boston. These are hydromorphic soils that are reactive to the climate and reflect the vintage, planted with Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot plus a tiny amount of very old Cabernet Franc. In terms of the Grand Vin and Deuxième Vin, Ségla, the latter comes mainly from satellite parcels that have expanded in acreage in recent years, though there is no formula that predetermines whether each parcel will end up in either.

The vineyards at Rauzan-Ségla.

François Baudoux is the current chef de culture. Médoc-born Baudoux actually began his career as a decathlete in the late 1980s before moving into vineyard work, starting at Château Barreyre in Arcins before joining Philippe Bascule’s team at Château Margaux. He worked at the First Growth for 12 years, making his way up the ladder and leaving in 2004 to manage Cambon la Pelouse. In 2011 he was appointed vineyard manager at Rauzan-Ségla, where he has applied a sense of viticulture raisonée and encouraged biodiversity, especially in terms of the soil ecosystem.

The current plantings include 62% Cabernet Sauvignon, 36% Merlot, 1% Cabernet Franc and 1% Petit Verdot (reintroduced by John Kolasa to “add a bit of seasoning”). The main rootstock is 101-14 with some 3309, 420A and Riparia. Just under 60% of the vineyard is planted at a density of 10,000 vines per hectares, the remainder at 6,666 vines per hectare, with an average vine age of 41 years for those used for the Grand Vin. Nicolas Audebert explained that they break the vineyard down into 21 separate plots. “The differentiation is made by the soil type between each terrace, vine age and orientation, and by observing the vegetal growth. We then refine the selection by zoning in upon different parcels. Tasting berries is an essential factor in identifying maturity. The 2016 vintage is a good example. Tasting the berries from Merlot vines oriented east–west on the plateau, we noticed a tangible difference in taste between the first row of clusters directly exposed to the sun and the others. Therefore, we harvested these parcels in two passages through the vineyard in order to fine-tune the vinification in terms of temperature [during fermentation] and extraction to suit their respective aromatics and structure. The results were convincing. We have gained precision and clarity of fruit and in the end we used both in the final blend. The vines are pruned double Guyot with a yield in accordance with vine vigor. The new plantings are at 10,000 vines per hectare with orientations modified so that the bunches are kept facing towards the sun.”

I asked about the vine

disease esca because it is a constant menace that should not be overlooked.

“We have vines touched by esca and there is no treatment against this disease. If the vine is infected, it has to be pulled up, so preventive work is critical. We take particular care concerning the selection of plant material and quality of rootstock since in the past they were not chosen with the same meticulousness.”

Since Thomas Duroux has guided Palmer towards complete biodynamic conversion, I wondered whether Steiner’s philosophy is something that Audebert is interested in pursuing. He replied, “At Rauzan-Ségla we take global ecological responsibility and look for inspirations in terms of different practices. This holistic approach is germane not only to the treatment of fungal diseases but also water management, waste treatment, our carbon footprint and so forth. The property will be certified Haute Valeur Environnementale (Level 3) in spring 2019. Biodynamics is an interesting methodology but one we don’t follow, since it’s just one of the ways you can rethink the impact of viticulture on the environment. Viticulture is essentially not a natural practice since we constrain the vine (something that winemakers like Lalou Bize-Leroy obviate by allowing tendrils to grow through the season). One of the interesting elements of biodynamics is the stimulation of the vine and soil vitality. The reduction in mechanical work in the vineyard is an objective and it has resulted in more activity of microorganisms and more earthworms. We fertilize using fresh manure and natural weed-killers, avoiding systematic use of phyto-pharmaceutical products for several years now. By using organic products and managing the vineyard as an interdependent ecosystem, we strengthen and stimulate the vines’ natural defenses. There is ongoing research that may influence the direction we take in the future, including experiments using ozonated water to protect the vine against cryptogamic attack and more precision in terms of fighting ver de la grappe (cochylis or grape worm) using puffers that act at night when the moths are most active.” Though Audebert did not mention it, they also use sexual confusion techniques as a natural defense barrier against cochylis.

Audebert then outlined how they approach the harvest. “We have a large team of pickers, 80 to 100 from France and Europe, split into four teams that go into the vineyard to inspect bunches for maturity. This has been done for the last four years and it has made a big difference in terms of precision. Having one, two, three or four teams on hand gives us flexibility in our daily work. We are able to approach the vineyard zone by zone and it enables better sorting on the spot. This first selection in the vineyard is crucial. We have different teams for Canon and Rauzan-Ségla, each supervised by permanent staff. Parcels are picked either entirely or not at all, according to our observations. Since 2012 we have used 6-7kg crates to transfer bunches and avoid crushing and oxidation, reducing the time it takes to transfer the fruit to the vat. Two sorting lines then inspect the incoming fruit at the reception, using two vibrating sorting tables, the first for the whole bunches and the second after de-stemming. We use human optical sorting – in other words, eyes and hands.”

The Rauzan-Ségla château building.

Vinification

Rauzan-Ségla can certainly lay claim to being one of the most picturesque estates on the Left Bank. Perhaps my impression is skewed, since my visits seem to coincide with sunny weather, but even so, it’s hard to resist the chartreuse-styled two-story building with mullioned windows and wisteria-clad walls, quaint turrets and half-exposed beams, bell-shaped curbstones and red antique roof tiles, all surrounded by ornate gardens decorated with palm trees. This estate seems perpetually tranquil, a place where you could easily idle away an afternoon absorbing the calm, hidden from the world outside this enclosed space.

As general director, Audebert is the decision-maker and face of Rauzan-Ségla, although in my articles I try to name-check “unsung heroes” working behind the scenes. One of them is Henry de Ruffray, cellarmaster for over 30 years. He helped with the élevage of the 1986 before joining Rauzan-Ségla in 1987 – not the easiest growing season for a debut. De Ruffray has been behind many of the new techniques introduced at the property. His wingman, Didier Larue, has been second in charge for 20 years. The scion of a winemaker at Château Latour, he commenced his career at Lagrange and then joined Rauzan-Ségla in the mid-1990s. Larue certainly deserves a mention, since he stepped into the breach when de Ruffray broke his leg in 2016. Eric Boissenot is the consultant, having taken over from his father.

Nicolas Audebert explaining something or other with Henry de Ruffray on his left.

There are presently 60 vats, ranging from 10 to 150 hectoliters in size in order to practice a more precise parcel-by-parcel vinification. The fruit is transferred into vat by gravity using cuvons, large stainless steel vessels hoisted manually above each vat, which is much more gentle than using pumps. The alcoholic fermentation is conducted using locally selected yeasts. There is no pre-fermentation maceration. The temperature increases to 26-27°C for the Cabernet Franc and Merlot, 27-28°C for the Cabernet Sauvignon and 25-26°C for the Petit Verdot. The duration of cuvaison is around 20 days for the Merlot and 22-24 days for the Cabernet Sauvignon. “For three years, we’ve done a co-inoculation that allows us to complete the malolactic before the wine is run off,” Audebert told me. “Running off and pressing are essential because the vin de presse is an important ingredient for the blending of the Grand Vin and Deuxième Vin. (The winery uses a horizontal SUTTER press. The vin de presse for each grape variety is graded before consideration for use in the blend.) All our oak comes from Tronçais and Limousin through seven cooperages: Taransaud, Sylvain, Nadalié, Berger, Demptos, Saint-Martin and Darnajou. The barrels undergo a light, slow, deep toasting in order to extract delicate wood tannins. We do around five rackings for Rauzan-Ségla and four for Ségla during the élevage over 18 months for the Grand Vin, using 60% new oak and 40% one year old. Ségla is aged for 16 months in 20-25% new oak. The satellite vineyards (where Ségla usually comes from) tend to impart the freshness we seek in Ségla. Even though it undergoes a slightly different élevage, we apply the same care and attention.”

I asked if they have been tempted to use alternative-size barrels such as demi-muids or clay amphora. Audebert said that they have not thus far, although he is interested. The wines are still racked traditionally by candles and fined with egg white before bottling.

The Wines

The vertical tasting was conducted at the château in May 2018. It was a small group that included just one other journalist, alongside Audebert and senior members of his team. Around 25 vintages were opened from their cellar, not just from the the well-known growing seasons but also several esoteric vintages that I rarely see. We tasted from youngest to oldest, though I describe them chronologically in order to interweave the story of the estate from 1900 to the present day. The notes are augmented with ex-cellar bottles poured at Bipin Desai’s vertical in Paris a few years ago, plus several from my own cellar, and one or two, such as the 2000, acquired from the market. For picking dates, blends and production, readers should refer to the individual tasting notes.

The vertical tasting in progress with de Ruffray in the foreground.

The oldest vintage that came direct from the cellar was the 1900 Rauzan-Ségla, a bottle that had lain unmoved for 118 years. It is a legendary growing season and the few 1900s that I have encountered have all lived up to expectations. This was no different. It was the final great vintage under Eugène Durand-Dassier; 1901 and 1902 were poor growing seasons and the estate was sold to Durand-Dassier’s son-in-law Frédéric Cruse in 1903. Cruse made two important decisions. First and foremost, he conducted a survey of his new estate with his manager, Charles Skawinski, whose family had been régisseurs at Pontet-Canet. From those records we can glean insight into this 1900 Rauzan-Ségla. Sixty-four percent came from ungrafted vines on their original roots, since at that stage only 20.1% had been re-grafted onto phylloxera-resistant American rootstock. The remaining vines were in poor condition and half were missing wooden stakes, so it’s no wonder Skawinski spent many years reconstituting the vineyard. What grape varieties did it comprise? Well, we can refer to Skawinski’s analysis of the vineyard in 1904, which showed 58.6% of plantings constituted Cabernet Sauvignon and Gros Cabernet (Cabernet Franc crossed with an indigenous Basque variety to create Hondarribi Beltza, then crossed with Fer), 6.6% Petit Verdot (a figure higher than I would presume), 1.2% Malbec and just 0.8% Merlot. The remainder was called a vieux mélange française – i.e., a hotchpotch of other French grape varieties. This 1900 was so remarkable that I quipped to Audebert that it is the best Rauzan-Ségla until the 2015. That was the truth. The wine exudes riveting precocity, richness and exoticism, the sucrosity offset by a killer line of acidity and almost honeyed on the finish.

Cruse’s second decision was to rename the wine “Rausan-Ségla” with an “s” instead of a “z.” Why? Well, he wanted to distinguish it from Rauzan-Gassies and reflect the “s” in his family name. To my mind, this change merely confused drinkers. The name reverted back to the “z” spelling when Chanel acquired the estate in 1994; however, late-released vintages that predate 1994 were stored unlabeled and will have a “z” in the name even though some of their corks might be stenciled with an “s.” I mention this just in case readers have bottles and fear they are counterfeit.

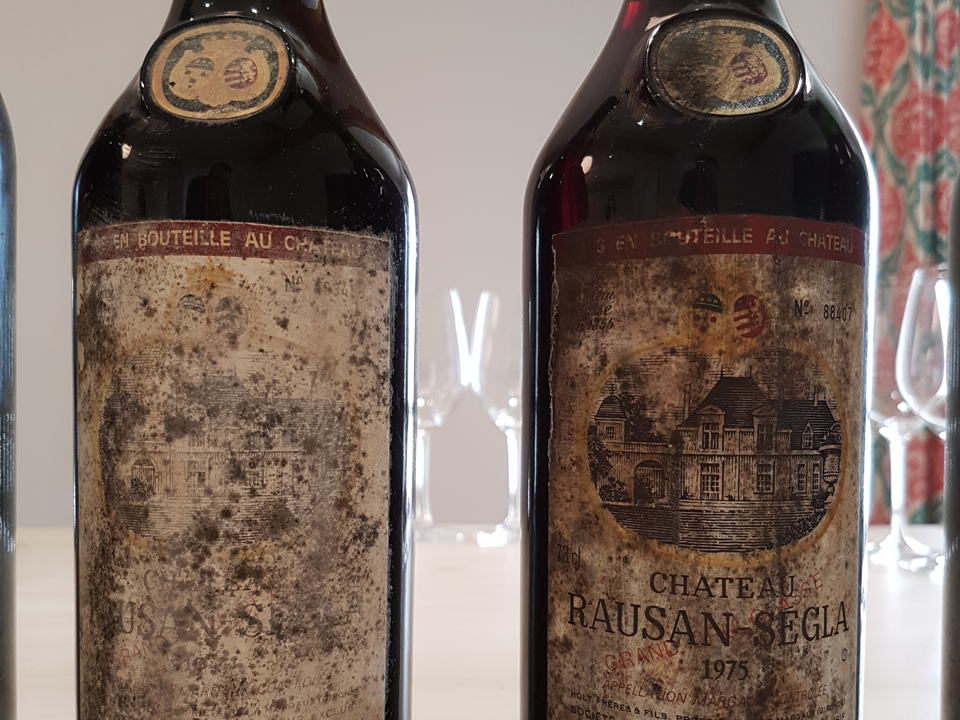

The most ancient bottles of Rauzan-Ségla served at the vertical.

The 1920 Rauzan-Ségla came from the Bipin Desai vertical in Paris and was the most venerable vintage shown on that occasion. It was the year that Frédéric Cruse finished construction of an observation tower, the small turret that hangs on the side of the main crenellated tower and where visitors taste the new vintage. It is rather light and serious, perhaps not quite equal to the best 1920s that I have tasted, though bottles with good provenance or in large format may still drink well. The 1929 Rauzan-Ségla, the second oldest at the château vertical and made by Charles Skawinski, was eclipsed by the 1900. Audebert seemed quite struck by the 1929, though I do not rank it among the best ‘29s that I have encountered. This may be because – as Clive Coates points out – the vineyard had begun to deteriorate, not receiving the care and attention necessary to perform at its peak. The impact of poor growing seasons and economic malaise can be seen in the breakdown of land use. A document from June 1937 shows that out of a total surface area of 55.46 hectares, just 12.9 hectares were dedicated to vines. Some 28.62 hectares were crops and wasteland and the remainder woods, pasture or gardens. There were two examples from the 1930s, but neither the 1938 nor the 1939 Rauzan-Ségla comes from benevolent vintages. These days you hardly ever see either in verticals, so I welcomed their inclusion. The former was moribund but the latter was better than expected, quite Burgundy-like in style with dried blood on the finish. Two postwar examples suggest that the division of proprietorship after the death of Frédéric Cruse caused the property to lose its way. The 1947 Rauzan-Ségla, tasted at the Paris vertical, was picked September 15–30. It was surprisingly leafy and suggests premature harvest, perhaps a panicked picking following such a hot summer and autumn. Better is the 1948 Rauzan-Ségla, which is quite stocky and serious, like many Left Bank 1948s, not complex but refreshing on the finish with a touch of brine.

By 1956 the vineyard had withered down to 20 hectares. Amongst all of Cruse’s estates, Rauzan-Ségla had been the most severely devastated by that year’s infamous Arctic winter, when temperatures plunged to –15°C. In a sorrowful letter to proprietors, he noted that the 1956 season produced 40 instead of 150 tonneaux. Cruse decided to sell the property to Bergerac-born Philippe de Meslon in December that year for Fr 15 million – a significant discount, since it had been put onto the market for Fr 25 million. Then again, considerable repair work was necessary. Meslon made the critical error of replanting vines using Merlot, the variety promulgated by authorities at the time (Château Giscours adopted the same policy and it also took them many years to address). His priority was quantity over quality in order to recoup his investment, to the inevitable detriment of both wine and reputation. There was a complete lack of investment in the winery, and apparently they continued to tread bunches by foot, the last major Bordeaux Cru Classé to do so. Meslon’s interest soon waned, and he sold the property four years later. The new owners were British, representing the first foray into wine by John Holt & Co., a company subsequently absorbed into Lonrho. At the same time, Holt purchased the distributor Eschenhauer, which remained Rauzan-Ségla’s exclusive distributor into the 1980s. This might be beneficial in terms of controlling markets and prices, though whenever a château is taken off the Bordeaux Place, it tends to disappear from general conversation and risks being forgotten.

The 1957 Rauzan-Ségla comes from a tricky growing season, so I can forgive its rather insipid showing. The 1959 Rauzan-Ségla, however, has no such excuse. To all intents and purposes, 1959 was the easiest growing season for years. The small crop filled five (or, more accurately, four-and-a-half) vats, reaching 11.8° alcohol in what was a warm and benevolent season. This bottle was cursed by a malodorous rubbery aroma on the nose, and to my surprise and disappointment, the palate was all over the place, riddled with volatile acidity. There is a question mark against my score: surely it could not have been this poor! And did that half-filled vat upend what would otherwise have been a fine Margaux?

In 1960 Jean-Pierre Joyeux became régisseur, taking over from his father, who had begun his tenure in 1937. In fact, Joyeux was born at the property and had worked at Rauzan-Ségla since 1944. The 1961 Rauzan-Ségla, which came from an ex-château bottle poured blind at a private dinner in Bordeaux, is better than the 1959: rustic and lacking finesse, a Margaux that might have undergone an excessively long élevage, but nonetheless retaining a fresh, marine-influenced finish. Bottles of sound provenance will still give immense pleasure. On the other hand, considering what Château Palmer achieved in 1961, there is no contest. Incidentally, readers should note that this was issued in a commemorative label to celebrate the tercentennial of Pierre Desmezures de Rauzan’s acquisition of the Rauzan estate. The 1962 and 1964 Rauzan-Ségla are a pretty lame pair, although the former has a redeeming nose. Take a look at the production figures that I include in the tasting notes: 688 barrels of the 1964 were produced, compared to 140 barrels for the 1959. Clearly, the owners were aiming to maximize production. Better is the 1966 Rauzan-Ségla, tasted at the Bipin Desai vertical, which is elegant and ferrous, fully mature but more vigorous than other vintages from this era.

Bottles from the 1960s and 1970s came in an unusual square bottle.

Alas, this did not improve the taste of the wine.

The 1970s is a poor decade for Rauzan-Ségla despite the old wooden vats being replaced by 12 epoxy-lined stainless steel vats in 1970. The 1970 Rauzan-Ségla is disappointing; consultant oenologist Emile Peynaud apparently complained at the time that it contained too much vin de presse. One of the biggest surprises during the tasting was the 1971 Rauzan-Ségla, which echoes the impressive performance of Palmer that year. Maybe the growing season benefited Margaux more than other Left Bank appellations. The 1975 is better but rather short, and the 1979 Rauzan-Ségla ran out of steam a while ago.

The 1980s is where Rauzan-Ségla should have left its troubles behind and begun to modernize. However, the owners were only now recognizing their long-term problems. In 1983 Jacques Théo was appointed to run Rauzan-Ségla. He finally began replacing the Merlot vines planted by Meslon in areas more suitable for Cabernet Sauvignon, though their benefit would not be exploitable until the vines reached maturity. The 1982 is missing because it does not boast a great reputation and I could not track down a reasonably priced bottle. My singular encounter some years ago was disappointing. The 1983 Rauzan-Ségla ought to have put the name back on the map, since it was a great Margaux vintage, but it is rather ordinary compared to Brane-Cantenac and Palmer, coming across somewhat soft and attenuated. Basically, it pays the price for the preceding years of underinvestment. Better is the 1986 Rauzan-Ségla. This benefited from a new cuvier equipped with eighteen 220-hectoliter and two 115-hectoliter temperature-controlled stainless steel vats and a second-year barrel cellar. There is more energy and cohesion on the nose compared to the 1983, and the solid, almost Pauillac-like finish is in keeping with the style of the Left Bank that year. Bottles should be broached now, as the 1986 will not improve further, though I suspect well-stored examples will give another 10 or 15 years of drinking pleasure.

One thing I never knew until researching this article is that the entire 1987 crop was declassified, a bold decision indicative of a resolve to improve quality to a level befitting a so-called “Super Second.” I reevaluated the 1988 on Vinous last year, so readers will find that in the database. The 1989 Rauzan-Ségla would be my pick from the decade, an indication that the estate was finally getting back on track. It exudes more elegance on the nose and palate, and after three decades it continues to show immense breeding and class. Market prices remain reasonable, though it is becoming more difficult to find these days. The 1990 Rauzan-Ségla benefits from a warm, dry growing season and a newfound resolve to create better wine than in the past, yet the dismal-to-ordinary vintages of 1991 to 1994 lay ahead. John Holt & Co. threw in the towel in spring 1994 and sold the estate to luxury brand Chanel.

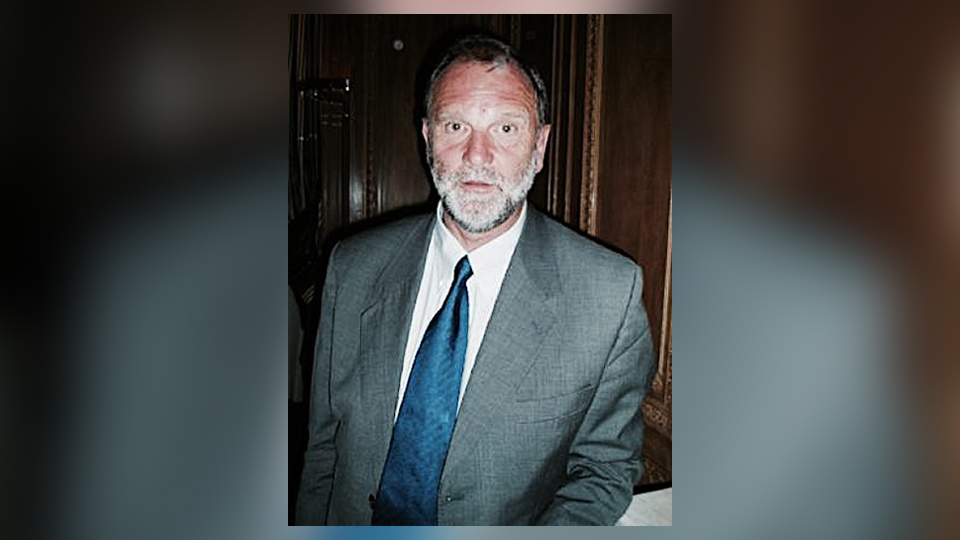

John Kolasa, here pictured around 2006/2007. He would always tell you how it is.

Chanel’s most significant decision was appointing John Kolasa, not just to run but to rejuvenate Rauzan-Ségla – and that he did. Kolasa received me at the property when I first visited in the late 1990s. Born in Dumbarton, Scotland, he initially trained as a French teacher and moved to France in 1971. After a brief period working on the Right Bank, he was commercial manager at Latour from 1987 until 1994, whereupon he took up the challenge of reinvigorating both Rauzan-Ségla and, two years later, Canon. Wisely, the Wertheimers, family owners of Chanel, gave Kolasa carte blanche to do as he saw fit. He was the perfect man for the job. He knew Bordeaux inside and out and yet, as a no-nonsense, straight-talking Scotsman, he could view the region from the outside, always a crucial asset. Many a primeur visit was extended just to absorb Kolasa’s wisdom (along with juicy, unprintable gossip). In 1995 he expanded the chai and constructed a new building to house the de-stemming and crushing machines, as well as a permanent bottling line. The number of vats was increased to 35 and at smaller and more varied sizes, ranging from 40 to 220 hectoliters. There was also a long-term reorganization of the vineyard: two hectares of Cabernet Sauvignon replaced by Petit Verdot in 1996 and three hectares of Cabernet Sauvignon re-grafted with Merlot two years later. This was in tandem with a much-needed new drainage system throughout the vineyard.

Kolasa not only improved the quality of Rauzan-Ségla, but also introduced much-needed consistency. This is clearly seen in subsequent vintages, not so much the rather masculine and charmless 1996 Rauzan-Ségla, but certainly in the superior 1998 Rauzan-Ségla,the first vintage that challenges the limitations placed upon it by the growing season and reasserts Rauzan-Ségla’s status as a bona fide Second Growth. Now at 20 years old, the 1999 Rauzan-Ségla is a decent wine for the vintage, a bit stocky and missing a little length, yet charming. It will not improve in bottle, so enjoy it now and over the next decade. The 2000 Rauzan-Ségla was not included in the vertical, and so, given the importance of the vintage, I bought a bottle. That was a good move, because the millennial vintage is just beginning to bloom and is, I feel, underrated by the cognoscenti. It is starting to drink beautifully: a quintessential Margaux with a disarming floral bouquet and gorgeous pure fruit on the palate. The 2001 and 2004 Rauzan-Ségla express a sense of sophistication that was missing in previous vintages. The 2003 Rauzan-Ségla is a misfire, forgivable considering the merciless heat that summer. (As an aside, I remember tasting the 2002s at the château that June, seeking shelter from the oppressive warmth outside.) The 2005 Rauzan-Ségla represents another step up in quality, fanning out with more conviction on the finish. The follow-up 2006 never quite slips into fifth gear. But the 2010 Rauzan-Ségla is turning into a fabulous, benchmark wine with newfound structure and a complexity that finally translates the propitious terroir. The 2011 and 2012 Rauzan-Ségla maintain the momentum.

Winemaker Nicolas Audebert of Rauzan-Ségla.

During en primeur in 2014, Kolasa confided that he would probably be

leaving his two Chanel-owned charges, Rauzan-Ségla and Canon. I must admit to

being surprised. He has so much energy and has been so proactive in promoting

his wines, such an integral part of the Bordeaux landscape, that I could not

imagine him countenancing retirement. Then again, French laws are stricter than

those of other countries in terms of making way for new blood, and in June 2015,

Kolasa officially stepped down and relocated to Arcachon. Stepping into his big

shoes was Nicolas Audebert. Born in Toulon and, annoyingly to us aging writers,

still in his 30s, he has a CV that includes Moët & Chandon, Veuve Cliquot

and Terrazas de los Andes and Cheval des Andes in Argentina. In 2014, Audebert

moved with his large family to Bordeaux in order to open a new chapter for

Canon and Rauzan-Ségla. He made an immediate impact, building on the work done

by Kolasa and elevating both properties to levels that would not have been

conceivable just a decade ago. Certainly the 2015 Rauzan-Ségla is a brilliant wine; together with the 1900, made

115 years earlier, it bookended this vertical in considerable style. Rauzan-Ségla

is finally back where it belongs – at the highest level in Bordeaux.

Final Thoughts

Rauzan-Ségla is a crucial Cru Classé within the Margaux appellation. For me, it occupies a sweet spot in terms of value: it can touch the quality of Château Margaux and Palmer and yet it remains affordable to most wine-lovers, a virtue too often lost within the pecuniary mindset of the Bordelais, where price is the barometer of success. (Then again, as this article has proven, that has been the case through the centuries.) The appellation would be cut adrift if it suddenly lost Rauzan-Ségla, a paragon of Margaux.

This vertical confirmed that throughout the decades there have been two Rauzan-Séglas, and I don’t mean one spelled with an “S” and the other with a “Z.” I refer to the splendid quality of recent vintages juxtaposed with the variable and too often disappointing quality of older vintages that sullied the estate’s reputation up until the 1990s. There are lengthy periods when the wine did not pass muster and relied upon classification and reputation to gloss over the undistinguished contents of the bottle. The fabulous showing of the 1900 highlighted what could have been made in great vintages such as 1929, 1947, 1959, 1961 or 1982, and offered a tantalizing glimpse of an alternate reality wherein Rauzan-Ségla challenged Palmer or even Château Margaux. The truth is that a combination of undemanding and misguided proprietors, a mis-planting of Merlot and a lack of investment conspired to make mediocrity the norm. Recovery began in the 1980s, but it was slow. It needed owners who cared about quality at any price, like the Wertheimers, and a manager to see it implemented, like Kolasa. They only arrived in the mid-1990s and even then, these things take time.

Nicolas Audebert has certainly given both Rauzan-Ségla and Canon a higher profile in recent years, taking quality to a new level and giving both crus an edge that was hitherto missing. He deserves all the plaudits that have come his way. I asked Audebert what the future hold. “In the long term, our goal is to continue to raise the quality of wine year after year so that Rauzan-Ségla becomes a reference point for the appellation in terms of the emotion it arouses, for professionals and consumers alike.”

Underpinning that goal is, of course, the t-word.

Terroir. Terroir. Terroir.

Terroir. Terroir. Terroir.

Yes, it is vital. But what we drink and love and share is wine. And finally, thanks to John Kolasa and now Nicolas Audebert and their teams, we can say that Rauzan-Ségla is truly a great one.

See the Wines from Youngest to Oldest

You Might Also Enjoy

An Education: La Dominique 1989-2015, Neal Martin, April 2019

Setting Sail - Malartic-Lagravière 1916-2013, Neal Martin, April 2019

What Nectar!! Suduiraut 1899-2015, Neal Martin, March 2019

A Test Of Greatness: 2009 Bordeaux Ten Years On, Neal Martin, March 2019

A Century of Bordeaux: The Eights, Neal Martin, May 2018