Browse using the new Vinous website now. Launch →

Printed by, and for the sole use of . All rights reserved © 2015 Vinous Media

Mugneret-Gibourg: Ruchottes-Chambertin 1945 – 2014

BY NEAL MARTIN | JUNE 5, 2018

“C’est un Chambertin vinifié à Vosne” – Henri Jayer describing Ruchottes-Chambertin

The trill of the telephone shatters the morning silence, shards of daybreak littering the bedroom and awakening the daughter. Drowsily she rubs sleep from her eyes, swivels her head to glance at the bedside clock. It’s early – nothing exceptional since her father’s practice means people call either before or after his surgery hours. The unanswered telephone seems to ring ever more urgently until syncopated footsteps are audible down the hallway and then her father’s unmistakable reassuring voice echoes up through the floorboards. On many occasions she has found herself eavesdropping upon his prognosis or advice, salving words spoken with almost paternal empathy. Her immediate thought is a medical emergency since he is one of the country’s most respected ophthalmic surgeons. Instead she recognizes the topic being that of the vine and not the eye.

“Bonjour Charles,” her father’s greeting spirals up from below. “Tout va bien? C’est un peu tôt, n’est-ce pas?”

“Georges, something has come up,” replies Charles, an old student friend from his days at University of Dijon. Charles is five years his senior, but they ran in the same circles, attended the same parties and chased the same girls. Georges nurtured a passion for wine, though his family is not winemaking royalty like Rousseau. Sure, the Mugnerets own a few plots here and there, though their wine sells for a handful of francs, part of the reason why Georges pursued a medical career to pay the bills. He can potter about the vines every Friday and Saturday; the occasional Sunday when the mood takes him.

Charles gets straight to the point.

“You often told me about wanting to add a Grand Cru to Clos Vougeot...”

“Correct,” confirms George with a tinge of resignation. “I’ve searched for years for a suitable plot, but it has never been right.”

“Always in Vosne-Romanée,” he chuckles. “You know, there are vines elsewhere.”

“And you know my father. He is born and bred in Vosne. He worked the land for many years. What is his expression? Vosne ou rien! I’m beginning to think that we’ll never find anything...”

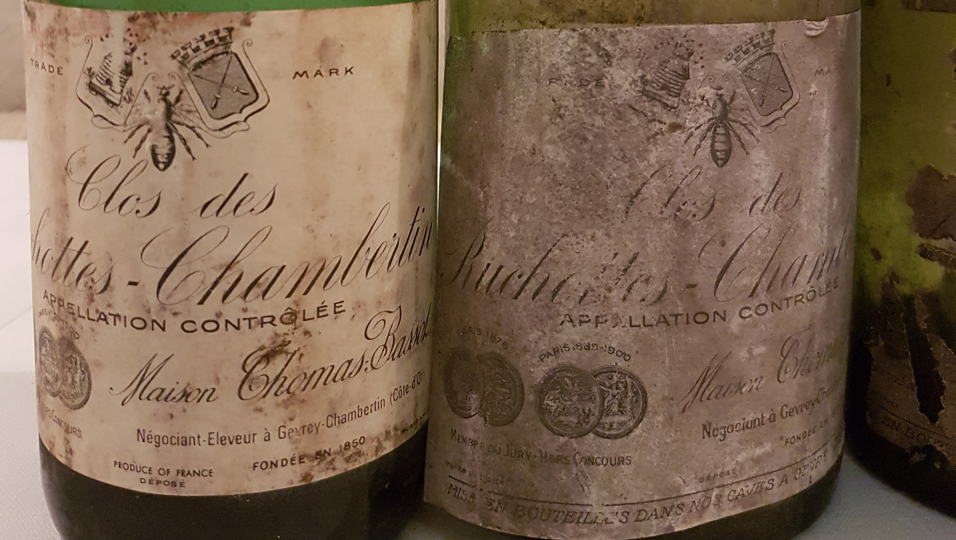

“Ah, well, that's exactly what I wanted to talk to you about. Something has come up,” Charles interjects excitedly. “You know Thomas-Bassot?”

“Yes of course. The négoçiant.”

“They are selling their monopole of Ruchottes-Chambertin. It is wonderful terroir. They made some terrific wines there in the 1940s and 1950s.”

“So are you going to buy it?” asks Georges, envious of his friend’s access to such a Grand Cru.

“That might depend on you.”

“What do you mean?” replies the doctor, a little startled.

“Well, it is a large area of vine. Over three hectares. I spoke to my wife and she’s always right. She said that it would be a lot for me to manage on my own, not just the money or tending the vines. I would need a bigger cellar to house all the barrels. What I am saying is that it is too much to take on myself. You’ve always said you wanted a Grand Cru. Would you consider sharing the purchase with me and one other interested party?”

The doctor pauses, his stomach roiling with excitement and trepidation. He ponders how his father, André, would react if the Mugneret family became winemakers in Chambertin. Like many, his father has always been hidebound to tradition and a parochial man at heart. Chambertin is renowned, but his father considers it another land, another country. It would be tantamount to treachery. Thoughts race through his mind with lightning speed.

“Charles. That is an interesting proposition but I need to discuss it with Jacqueline and my father.”

“Doctor. I need a quick answer. I only have two days to put together a proposal.”

“Two days? Seriously?”

Georges weighs up the proposal. It has come like a bolt out of the blue. Perhaps it is his only opportunity to acquire a Grand Cru. Is he really going to turn it down and disappoint one of his closest friends?

“So it would be a three-way division of the vineyard?” George enquires.

“Yes. The other person I intend to approach is a successful businessman from Rouen, Michel Bonnefond. He is also interested in buying a well-regarded vineyard and knows Georges Roumier who would take the métayage. My only request...”

“If I wish to proceed...”

“...if you wish to proceed, is that I would like the part known as Clos des Ruchottes. You probably know that it’s an actual stone walled vineyard with a pretty stone gateway. Perhaps you could take the lower section, Ruchottes du Bas. That’s an interesting vineyard with a lot of potential. But I need an answer.”

Upstairs his daughter listens to the exchange, a quicksilver mind crammed full of physics and chemistry. She knows that it would be a significant purchase.

“D’accord. Give me a few hours to find the money. I can’t promise anything. I need to speak to my father and the bank, see if I can gather the money at such short notice. The banks do not see vineyards as good investments. You only have to look at the pitiful prices of Burgundy wine to see that.”

“I understand. Maybe one day people might want a bottle of Armand Rousseau or Mugneret instead of Claret,” says Charles laughing. “Wishful thinking I suppose. Let’s speak later.”

“Tout à l’heure Charles.”

His daughter has held her breath the entire time and finally exhales. She wants to run downstairs and speak to her father but remains under the bedcovers, conjecturing what will happen if the bank agrees to lend them the money. What will be will be...

(...continued at the end of this article)

The above story is a dramatization of events in the Mugneret household, derived from my conversation with the aforementioned daughter, Marie-Christine Teillaud, when we sat down to discuss the origins of the domaine. A few weeks earlier I had attended a magnificent vertical tasting of Mugneret/Mugneret-Gibourg’s Ruchottes-Chambertin in London that had been organized by Daniel Johnnes with the assistance of Jordi Oriols-Gil: a remarkable and virtually unrepeatable retrospective that not only spanned almost the entirety of Mugneret/Mugneret-Gibourg’s tenure of the Grand Cru, but ventured further back to the Thomas-Bassot era. This article is based around that vertical and their Ruchottes-Chambertin vineyard, though I have added additional tasting notes from the domaine’s other holdings.

Stunning array of Ruchottes-Chambertin from Thomas-Bassot, Georges Mugneret and Georges Mugneret-Gibourg.

When we sat down to discuss the domaine, I began by asking Marie-Christine about the origins of the domaine. The proliferation of “Mugnerets” in the locale evidences multiple strands of the family over many generations, the etymology of the name from “meunier” or “miller”. According to Clive Coates writing in “Grand Vin”, the Mugnerets were so numerous and caused such confusion that Georges’s letterheads were headed by the words: “En raison des homonymes, prière de préciser noms et prénoms”.

“The beginning of the story starts with my grandparents, when my grandfather André Mugneret married Jeanne Gibourg in 1928,” Marie-Christine explains. “My father Georges Mugneret was born in 1929 and he was their only child. (In fact, Georges turned out to be the family’s last newborn boy until the X and Y chromosome matched again in 2016.) In 1930 André and Jeanne bought the house in Vosne and three-hectares of vineyards in Bourgogne, Nuits-Saint-Georges, Vosne-Romanée and Echézeaux. The maison was built in 1750. You can see the plaque mentioning the date of its construction when it was under ecclesiastical ownership by the Abbé de Citeaux.”

With a home in Vosne and a small scattering of vineyards, they duly appended their names to create Domaine Mugneret-Gibourg in 1933. The maison in Vosne-Romanée lay in the heart of the village next door to the Lamarche and Gros families. The large and quite imposing three-storey, L-shaped house overlooking the courtyard was sufficiently large to be divided into two: one part inhabited by the family of Jean Gros and the other by André and Jeanne. In 1953, aged twenty-four, Georges bought a parcel in Clos Vougeot from Léonce Bocquet when, as Marie-Christine commented, he was just a student. I wonder if he was motivated by his father selling the family’s original plot of Clos Vougeot in the 1930s, a desire to undo André’s decision, though in those dire times, André might well have been trying to make ends meet. Five years later in 1958, during his military service in Algeria, he met Jacqueline, a schoolteacher, and the couple married upon his return to France. They moved to Dijon with their firstborn daughter, Marie-Christine. Her father’s time consumed by his busy practice and her sister Marie-Andrée not arriving for another ten years, Marie-Christine was in short supply of friends her age. So she like nothing more than join her father at weekends in Vosne, playing in the courtyard with Jean’s children, Michel and Bernard Gros, or perhaps out in the vines. The closeness between the Gros and Mugneret families continue to this day. Marie-Christine’s grandchildren are friends with Michel and Bernard’s own.

“My father Georges found working in the vine very hard and since the wines were sold for little, he didn’t have much money. That is why he became an ophthalmic surgeon. But he loved the vineyard and the wines. He came down here most weekends. To my father, vines were very important and he always felt the urge to buy more parcels even though my grandfather told him he was crazy. He often sought advice from Charles Rousseau and looked up to him both because he was older and because of his reputation as a winemaker.”

In 1971, George Mugneret expanded his holding with an acquisition in Les Chaignots in Nuits-Saint-Georges. As we know, Ruchottes-Chambertin followed in 1977 thanks to Charles Rousseau, then later Nuits-Saint-Georges Les Vignes Rondes in 1982 and Chambolle-Musigny Les Feusselottes in 1985. Crus from parcels acquired by Dr. Georges Mugneret were labeled under “Domaine Georges Mugneret” whilst “Domaine Mugneret-Gibourg” applied to his father André’s holdings. They were essentially one and the same, a slightly confusing distinction that lasted until August 2009 when, following the retirement of Jacqueline, they were unified under “Domaine Georges Mugneret-Gibourg”.

The vineyard of Ruchottes-Chambertin looking south with some mesmeric oyster shell-like clouds above. Before you ask, this photo is untouched with no filter.

Marie-Christine told me that in the early days Georges Mugneret was always seeking to bottle around 40% of the total production in barrel but during the 1960s and 1970s it was difficult to find competent coopers. She remembers in the early days Georges pleading with them to purchase oak barrels, though in the end he managed to mature his new Grand Cru in around 50% to 65% new barrels. His maiden Ruchottes-Chambertin coincided with the inauspicious season of 1977. Sure, the great 1978 vintage lay around the corner, though it was not necessarily his favorite early vintage...

“My father was very proud of the 1979 vintage of Ruchottes-Chambertin,” Marie-Christine recalls fondly. “My mother said he was so happy with this wine that he always opened a bottle for friends and clients. One day she told him to stop because there were hardly any bottles left, about nine bottles. He was like a child. There was a small stash and she said he was not allowed to touch it.”

But there was another side to Georges Mugneret, a man restless and rarely contented with the quality of his wines, notwithstanding the 1979.

“My father was often not happy with the results [of his wines]. He was not an optimist. He would say: “I’m going to stop making this cuvée.” I remember the 1982 vintage was a large crop but he was unhappy with the wines. That was in the days when there was no green harvesting. My mother was more optimistic, so they were good together.”

Apart from expanding his parcels of vineyard, Georges Mugneret also felt that his label needed to be more visually attractive. The original of the painting that adorns the range hangs in their refurbished ground-floor tasting room. “We used the old label up until 1985, the one depicting a stained glass window. For us it was a bit serious and austere and we wanted to change the style. We spoke with a designer in Nuits-Saint-Georges and the only stipulation was that we wanted to keep Saint Vincent. After two hours of explanation, he understood what we wanted and told us we would meet up the following week. He came with this drawing and we said why not? I cannot remember his name. I remember my father asked Robert Parker what he thought of the label. We thought there was a lot of color and energy. Funnily enough, Japanese people see it as a Chagall.”

Everything seemed to be in place. Georges Mugneret had the Grand Cru that he always desired, his daughters had clearly inherited his gift for chemistry and medicine and he could easily commute between Dijon and Vosne. Indeed, by now his career and the attendant financial stability meant that he could retire from his practice and devote himself entirely to his vinous passion. However, tragedy lay ahead.

“My father gave up his medical practice in 1982, though it was just coincidence that he was diagnosed with cancer that year. He recovered and he went for check-ups every twelve months. After that he was working full-time at the domaine since, by then, his parents were too old. In February 1988 the cancer came back and so I stopped working as a chemist because we knew he did not have long. My father passed away in November 1988 so he still saw the vinification for that season. That made it a special vintage for us.”

I ask Marie-Christine how prepared she was at that time. Of course, her widowed mother Jacqueline stepped up to the plate and by all accounts, it is thanks to her resilience and fortitude that the domaine survived. But clearly the future security of the domaine depended on the next generation – Marie-Christine and later, Marie-Andrée. Marie-Christine had been awarded a doctorate in pharmacy in 1983, her thesis title: “Is Wine A Medicine?” Suddenly she was thrust from the philosophical side of wine to its practicalities and realities, all the time gaining valuable experience.

“Well of course I had been working as a chemist but I helped my father during the vinification and bottling, which was often at the weekend. I wanted to go out with my friends so sometimes I was not too happy. But I learned a lot working with him. The 1989 vintage was my first, when Marie-Andrée was still a student. I remember that it was so hot during the harvest and bunches were so warm. It was difficult. These were my first steps and there was no mother or father to help you at that exact moment.”

I ask Marie-Christine if she considered asking Charles Rousseau for help, after all, he was a family friend. His sage advice would have been priceless. Marie-Christine pauses and reflects, as if she had never entertained that option until now. Obviously it must have been a stressful time and it takes a moment for her to gather her thoughts...

“I suppose I never thought to ask him. Jacques Seysses (of Domaine Dujac) came and offered help for the first vintage because my father had helped him when he started. He was a good friend of my father. At that moment the 1987s were in barrel and there was a new vintage, the 1988. There was always something to do, day after day. Every day there was a crucial decision to be made. It was unrelenting.”

Despite Jacques’s assistance, I get the feeling that Marie-Christine felt alone at this point, despite the support of her husband Eric and mother Jacqueline. She must have felt besieged by circumstances triggered by the loss of her father, the instability that it wrought. Nature pays little heed and does not pause to sympathize when tragedy transpires, just ploughs into the next vintage that must be cared for and nurtured.

“Things changed in 1990,” Marie-Christine explains. “But the most important vintage was in 1993 because we changed the way of doing the harvest. We bought a sorting table and had to buy smaller baskets. There was no longer crushing of the grapes as they were bought into the winery and the quality of fruit was higher.”

From the left: vineyard manager Florent Lompré, who has worked at the domaine since 1999, Marie-Christine and younger sister Marie-Andrée.

Throughout the 1990s, the reputation of Mugneret-Gibourg began to rise. Marie-Andrée qualified as an oenologist and took some of the burden away from her elder sister. For many years she has been in charge of viticulture whilst Marie-Christine oversees the winemaking. Of course, her scientific background has always stood her in good stead. The vineyards are treated lutte raisonnée, eschewing the use of herbicides and insecticides. Instead of green harvesting they prefer ébougeonnage or de-budding early in the season. During Georges Mugneret’s time around one-fifth of the stems might have found themselves in the vat, but during the 1990s the entire crop was de-stemmed. Nowadays partial stem addition is used, depending upon the vintage.

Given the scientific leanings of the family they have not been averse to using clones in the vineyard, selected yeasts during the alcoholic fermentation or chaptalization at the end of fermentation added judiciously in two or three stages when necessary, not to increase alcohol but to prolong the conversion. Most of the barrels come from François Frères, Rousseau and Berthomieu, utilizing the first two more for the Grand Crus since their imprint is heavier upon the wine and the latter more for the Village Crus. The total élevage is between 18 and 21 months, blended into tanks before bottling when a light fining might be used. I remember Marie-Christine once advising me upon the importance of bottling insofar that a potentially great wine can be spoiled at the last moment, just before the cork is inserted, if you stop paying attention.

The Vineyard

Daniel Johnnes brought two rocks to compare the different terroirs. The whiter one on the left is oolithic limestone from Clos des Ruchottes owned by Rousseau. The sandy-coloured rock comes from the parcel owned by Mugneret-Gibourg, clearly containing less limestone that engenders a more deeper and powerful, perhaps less mineral-driven Ruchottes-Chambertin that that of Rousseau.

Before broaching the wines, we should pause to examine the vineyard that is the focus of our attention. Ruchottes-Chambertin covers 3.3036 hectares and can be seen as the first or most northerly of a spine of Grand Crus up to La Tâche in the south. It nestles just outside the village of Gevrey between Mazis-Chambertin to the south and the Premier Crus of Fonteny to the north at the base of the “Combe de Lavaux” that channels in cool air. It is a comparatively steep Grand Cru, especially in its higher reaches. Mugneret-Gibourg’s crown jewel is a 0.64 hectares parcel in Ruchottes du Bas where the soil is slightly deeper and not dissimilar to those in Clos-de-Bèze to the south. Despite the propitious terroir, of course, vines are mortal. “We pulled out part of Ruchottes-Chambertin in 1998 and replanted in 2000. The vines had just got very old and they were becoming unproductive. Plus there was another part with a lot of disease. The first production [from the replanted vines] came in 2002 and we decided to separate it from the Grand Cru, declassifying this section to make a Gevrey-Chambertin Village until 2007. In 2008 we classified it as Gevrey-Chambertin 1er Cru until the 2012 vintage when it was blended with the rest of the vineyard because the yields were so small. It was not worth bottling them separately. I think it is interesting to blend these old vines, around 60-years old now [actually planted in 1950] with the younger vines,” Marie-Christine explains.

The Wines

Our vertical tasting began in the final days of the Second World War, when Ruchottes-Chambertin was under sole proprietorship to Thomas-Bassot. I am unsure exactly when they assumed proprietorship although Camille Rodier notes at least partial ownership along with several others in his 1920 report on the Côte d’Or. I presume that during the economic doldrums of the 1930s Thomas-Bassot bought up growers’ holdings. I have been fortunate enough to taste some of these wines before, namely when I participated in a vertical of Ruchottes-Chambertin from Armand Rousseau back in 2013. Suffice to say that given their age, bottles can be a hit and miss. But when they do “hit” I can vouchsafe their brilliance.

Alas the 1945 Ruchottes-Chambertin had an odd nose, not corked or decrepit, but seemingly affected by some kind of bacterial infection. That would not be a surprise given what surely were unimaginably difficult conditions back in those days. The 1947 Ruchottes-Chambertin however, was a gem. You expect a richer style of wine given the warmth of that growing season, even after seven decades. I was astounded by its elegance and transparency, vivacious and vivid after so much time had passed. There was the lead-up to the transcendental 1953 Ruchottes-Chambertin, a wine destined to be in my top ten bottles of the year. The previous bottle in 2013 was faulty, but this was endowed with a captivating, concentrated bouquet undiminished by time, the palate following suit with fine tannins, sensual red fruit and ineffable complexity. The 1964 Ruchottes-Chambertin was dead on arrival, but the 1969 Ruchottes Chambertin was elegant, a little timeworn maybe, but clean and still willing to give drinking pleasure.

The modern era for Ruchottes-Chambertin begins in 1977 following the tripartite division following the sale of Thomas-Bassot to Boisset. The 1977 Ruchottes-Chambertin comes from a maligned vintage that most oenophiles ignore or revile. That is foolish with respect to Burgundy and this 41-year old puts in a creditable performance despite a touch of TCA on the nose. There is certainly satisfying depth and whilst not a complex Grand Cru, one can tell that this comes from a propitious vineyard. As you would expect, the 1978 Ruchottes-Chambertin is much better, with plenty of fruit, rustic, smooth in texture with graceful finish. It has the substance you expect from a 1978 and at nearly 40 years of age, would appear to have another decade in the tank. As we have discovered, Dr. Georges Mugneret always had a soft spot for the 1979 Ruchottes-Chambertin. Comparing the two side-by-side, I feel that time has been kinder to the 1978, although the 1979 remains an impressive wine for the vintage. It just does not have the same weight and fruit concentration, attenuating slightly towards the finish. Later on, I was lucky enough to encounter a magnum of the 1979 at a La Paulée in Beaune and this was much better than the bottle: fine tannin, more vigorous and with a beautiful pure, timeworn finish.

Throughout the 1980s Dr. Georges Mugneret oversaw the winemaking, intermittently helped by his daughter Marie-Christine. Taking the entire lifespan of Ruchottes-Chambertin under Mugneret into consideration from 1977 to the present day, I feel that the 1980s did not produce the most auspicious Burgundies. In fact, Clos Vougeot was the domaine’s best wine. Granted, neither the 1983 or 1984 Ruchottes-Chambertin emerge from great Burgundy vintages and yes, given the wretched reputation for the 1984 vintage, the doctor did well that year. The 1985 Ruchottes-Chambertin is splendid, as it ought to be given the benevolent growing season, although I would argue that subsequent vintages during the 1990s and 2000s ultimately matured into wines with more breeding. Wishing not to detract from the delicious 1985, it just does not quite express the mineralité and precision of later vintages. Part of the reason might be that the domaine still practiced what in retrospect was rudimentary winemaking without today’s painstaking meticulousness and more prevalent use of the vigorous SO4 rootstock out in the vineyard. The 1988 Ruchottes-Chambertin coincides with the passing of Dr. Georges Mugneret and his daughter, invidiously handed responsibility, suddenly had to make critical decisions. It seems mean to criticize the wine given the circumstances, but contrasted with other vintages, the 1988 and indeed, both the 1989 and 1990 Ruchottes-Chambertin are “capable” but not bona fide great wines. They pass muster without excelling, without aspiring to reach the heights of the 1978 or 1996 or 2005.

Moving into the 1990s, the key event is 1993 when the domaine introduced a sorting table and the quality of fruit entering the vat improved. The 1991 Ruchottes-Chambertin augured well for the future and might be Marie-Christine’s first genuine success, even if it does not quite match subsequent triumphs. Unlike the previous three vintages it conveys more terroir, more precision and simply ratchets up aromatic purity and complexity. The 1993 Ruchottes-Chambertin is the point where the wine improves to a level that I relate to recent vintage. We can see greater articulation of the terroir, greater clarity vis-à-vis earlier vintages, the recently acquired sorting table instantly meliorating the wine. The 1996 Ruchottes-Chambertin sees everything come together. Like so many Grand Crus from this vintage, it is evolving at a glacial pace and arguably it does not possess the grace and elegance of later vintages. But there is tremendous structure and it might simply be a case of waiting a few more years for it to dispense with a slight toughness. How much patience do you have?

The 1998 Ruchottes-Chambertin does not show well. I suspect there is something not correct with the bottle. This was compensated by the magnificent 1999 Ruchottes-Chambertin, a wine that successfully combines the horsepower of the growing season with the finesse of the terroir. It is firing on all cylinders, a bravura Grand Cru that is blessed with a wonderful sorbet-fresh finish that leaves you wanting more.

Marie-Christine drawing some of her 2016s from barrel.

Moving into the 21st century, I feel that the domaine’s wines improve further. Marie-Christine and Marie-Andrée fine-tuned every stage of the process from vine to bottling. The 2000 Ruchottes-Chambertin is a triumph considering the challenges of that up and down growing season, a Grand Cru that is beautifully balanced and tensile, nimble and as vivid as a crisp spring morning. It skips like a young and happy child across the senses. The 2002 Ruchottes-Chambertin was born in one of my favorite vintages in recent years and it revels in a growing season that brought out the best in Pinot Noir. Graceful and elegant, these 2002s are turning out to be ballerinas, pirouetting across the stage. As I comment in my note: peer into the glass and you can almost see the terroir. The 2005 Ruchottes-Chambertin is cut from a different cloth to the 2002 and serves as one of the highlights of the vertical. Here one can witness intensity and precision completely simpatico, a newfound sense of mineralité that infuses every atom of this wine. Some Burgundy winemakers have remarked that in retrospect they may have pushed the 2005s too hard, as they were wont to do in those days. Sometimes that is true – but not here. Looking back now it portends more recent vintages such as the 2010 and 2012. Finally, the 2009 Ruchottes-Chambertin is not dissimilar to the 2005 although without quite the same breath-taking symmetry; plusher as you would expect, yet utterly seductive.

Final Thoughts

Readers will already be aware of my appreciation towards Mugneret-Gibourg. I first visited the domaine in the late 1990s when I was received by Jacqueline and Marie-Christine. In my opinion there have always been two constants. Firstly, the sheer drinkability of the wines because you never see a drop left inside a bottle whenever a Mugneret-Gibourg is opened. They bestow so much drinking pleasure that they are irresistible from start to finish, a proclivity to blossom and evolve with aeration. In recent years, their sensory virtues have been accompanied by an increasing level of profundity, complexity and precision within their top crus. Inevitably this has meant that Mugneret-Gibourg has become one of the most sought-after domaines. The second constant is the affability of the family, always with a smile on their faces. I am probably not the only wine writer that wishes all winemakers were as friendly and charming as these two sisters, always so self-effacing and down-to-earth. It is reassuring to see the next generation playing an increasingly important part in the domaine as Marie-Christine’s eldest daughter Lucie has joined in my recent visits, clearly taking a more active role and being carefully handed the baton.

This vertical tasting enhanced my appreciation for the domaine’s Ruchottes-Chambertin. That does not infer that every wine touched perfection – far from it. These vintages narrate the vineyard and the unfolding story of the Mugneret family, with all the ups and downs that entails. Since the reunification of the younger vines with the older vines in 2012, the Ruchottes-Chambertin has achieved new heights, as attested by my laudatory review. Though my fascination lies with the older vintages, it is clear that the finest expressions of their Ruchottes-Chambertin, indeed their entire portfolio, has taken place over the last seven or eight years, partly because of the meticulous care and investment in recent years, partly because they gradually replanted the vigorous SO4 rootstock that was prevalent in the 1980s to less vigorous rootstocks such as 161-49. The domaine is in good hands under Marie-Christine and Marie-Andrée. I think their father would have been extremely proud to see how the domaine has progressed since his passing.

Before we go, let us complete the story of the Mugneret’s acquisition of Ruchottes-Chambertin. We all know that Dr. Mugneret agreed to Charles Rousseau’s proposal, however, as Marie-Christine related in our conversation, the doctor’s father André had to be persuaded...

(Continued from the opening story...)

It is November 1977 and Georges is down in the cellar underneath the house in Vosne-Romanée, joined by his father André and uncle. Georges has invited him to taste his new “baby”, the 1977 Ruchottes-Chambertin that has been pressed and transferred into barrel. To say that Georges is nervous is an understatement. His father only reluctantly acquiesced to invest into the Grand Cru. Deep inside, Georges knows that he would have preferred to hold out for a choice premier cru in Vosne-Romanée to come up for sale. Nothing can be done about that now. Georges dips the pipette into a barrel and fills his father’s glass with iridescent, nascent Pinot Noir. The arched brick cellar lacquered in black mold is eerily silent, only the sound of wine sloshing in mouths. Georges is on tenterhooks. “Say something, anything” he thinks to himself. Yet both his father and uncle do not utter a word. Finally, he asks what they think of his wine.

“Ce n’est pas un vin de chez nous,” comes André’s devastating answer. It is not a wine of ours? Diplomacy was never his forte. The words crush his son. He had anticipated at least a glimmer of enthusiasm, however, both his father and uncle are traditionalists, unable to countenance wine whose crime is not to be born in Vosne-Romanée. Georges gathers himself and undefeated, invites them to re-taste, explaining the style of Ruchottes-Chambertin. They reluctantly take another sip and this time there is a sense of understanding. They are just unaccustomed to Burgundy without the seductive floral scents of Vosne-Romanée and only gradually appreciate the facets of mineralité and the mouthfeel of structure. His father is laconic in the best of times, habitually offering just a terse “yes” or “no” when adjudging wine. Georges glimpses his father’s inchoate appreciation.

“Don’t worry,” his father assures. “I was the same when you bought Clos Vougeot. It took me a while to understand.” Sure enough twelve months later when he tastes the 1978 Ruchottes-Chambertin, he breaks into a grin, puts a hand on his shoulder and says: “My son. You were right.”

(My sincere thanks to Daniel Johnnes and Jordi Oriols-Gil for organizing this tasting, particularly to Marie-Christine Teillaud for both her time discussing her father and the domaine.)

You Might Also Enjoy

Life Is Funny Like That: 1999 & 2015 DRC, Neal Martin, April 2018

The Magic of d’Auvenay: 1989 – 2011, Neal Martin, March 2018

The Glorious 1999 Red Burgundies, Stephen Tanzer, March 2018

Domaine Leroy: The 2015s From Bottle, Antonio Galloni, March 2018

Red Burgundy 2016 and 2015: Two Terrific but Very Different Vintages, Stephen Tanzer, January 2018