Browse using the new Vinous website now. Launch →

Printed by, and for the sole use of . All rights reserved © 2015 Vinous Media

Mirror Image: 2016 & 2017 Chablis

BY NEAL MARTIN | AUGUST 9, 2018

Chablis articulates terroir with greater transparency than any other wine region. That is quite a bold statement. However, in my view Chablis translates the nuance of land through the prism of wine with a degree of clarity that is its strength and its weakness. Reliant on a single variety from vines precariously perched on the northern latitudinal boundary of viticulture, at constant risk of frost and spontaneous hail, with a proclivity to eschew wood for stainless steel – Chablis gives winemakers little room for error. It is winemaking on a knife’s edge. Yet the benefits are there for wine-lovers to relish. Aromas bursting with scents that evoke images of dew-dappled Granny Smith apples emitting an audible “crunch” when you bite into them. That tang of struck flint. The tension and energy sprung-loaded into great Chablis, the subtleties between various Premier and Grand Crus and mineralité suffused into every mouthful. In talented hands Chablis can satisfy both the senses and the intellect. As I have written before, a friend once opined that Chablis should not kowtow in front of the wine-lover, do whatever it takes to please. “Chablis should be mean,” he averred, implying that the finest Chablis wines are uncompromising, challenging and cerebral. I concur. The world is full of fabulous Chardonnay but only few of them can call themselves Chablis. So why not be different? Why not ask questions? Why not encourage the oenophile to pause and reflect upon what they are drinking? Where else offers a mirror image of land and season like Chablis?

Looking up towards the Grand Cru of Les Clos

I adore Chablis. As soon as I turn off the autoroute and the land spreads out into endless nothingness I feel instantly at ease. I leave my troubles behind. Upon entering the quaint, picturesque and slightly timeworn town of Chablis, I pass by the River Serein and gaze towards the slopes of Grand Crus. I am immediately soothed by the tranquil atmosphere. Everything in Chablis is just bijou. On my first day when I awoke at my hotel, I spent the morning tasting at the BIVB offices and then visited four growers (Raveneau, Eleni Vocoret, Patrick Piuze and Vincent Dauvissat) leaving my car in the hotel car-park because it takes about three minutes to walk from one to another. There’s no other region I think I could do that, and yet Chablis always feels a bit “empty”. It might be contentious to say, but I feel that cognoscenti have overlooked Chablis in recent years, their horizon stretching little beyond Puligny-Montrachet or Meursault. Chablis is so entrenched in people’s minds and so universally recognized, that it is taken for granted, it has almost become a peripheral part of Burgundy. How many pilgrims to the Côte d’Or actually drive up the A6 to Chablis? It only takes an hour.

Why bother?

It will still be there next year.

Hail nets used in Les Clos; this photo was actually taken in May, prior to the INAO’s authorization of the use of hail nets

As a consequence, Chablis land prices remain lower than the Côte d’Or, a boon to cash-strapped younger vignerons who are now beginning to migrate north and bit-by-bit, rebalancing a region that for many years was dominated by co-operatives. For consumers, prices have always languished below its peers in Meursault or Puligny-Montrachet, at least beyond the Raveneau/Dauvissat axis. It means there are bargains galore if you know where to look, especially since more and more winemakers have upped their game to create an expanding choice of growers currently making seriously fine wine. This report takes a look at the two most recent vintages from a week of tasting in the region: visiting growers and tasting blind at the BIVB. I hope that it conveys the essence of a region that is really becoming one of the most exciting in Burgundy, a region that currently offers value-for-money that lies in stark contrast to some of the inflated prices down in the Côte d’Or. Basically, if you are thinking of getting into Chablis, of maybe reigniting your interest, then the time to do it is now.

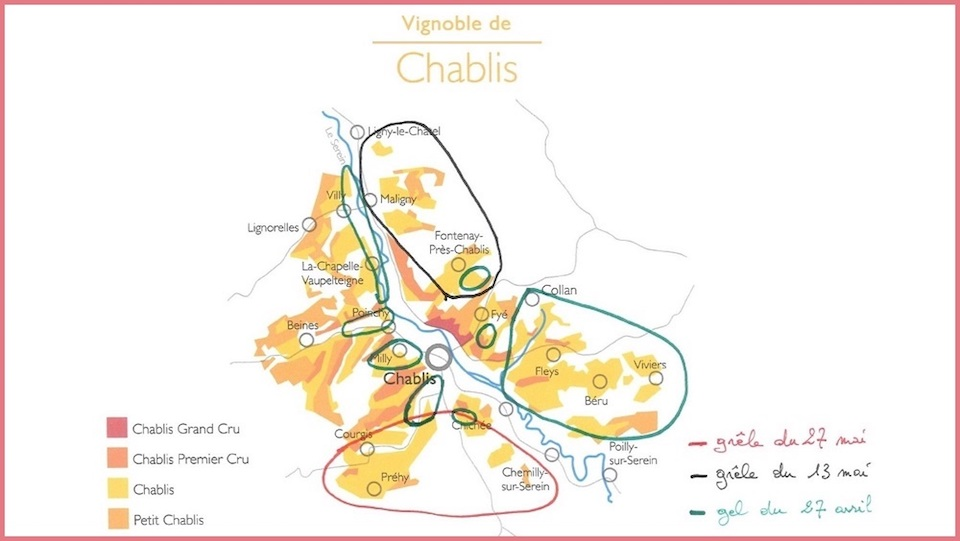

Didier Séguier, William Fèvre’s winemaker, drew this map, which depicts areas that were damaged during the hail and frost episodes of 2016

The 2016 Growing Season

The 2016 growing season commenced with a warm January and February, but by March warning bells began to toll as temperatures plummeted to around 30% below average. The cold climes continued into April when temperatures lagged 15% below normal. Then on 26 and 27 April, an acute frost struck and affected parts of Chablis that were presumed to be risk-free. Furthermore what the BIVB described as a “glacial wind” compounded the damage. “Candles”, the gasoline-fuelled heaters placed across vineyards to raise the ambient temperature of the vineyard were positioned in mostly Grand Crus, whilst many sought to spray the vines with water so that the buds would become encased in ice and thus protected. With several consecutive nights of frost, this was only partially effective and of course, many growers simply exhausted their supply of candles. This was followed by hail on May 13 that wrought damage through Chitry, Corgis, and Préhy then diverted towards Chichée, instead of heading toward Montée de Tonnerre. Patrick Piuze recalled that the vineyards looked like winter after pruning. Then a second hailstorm arrived on 27 May, on the route from Ligny-La-Châtel down to Maligny and towards Chichée. Chablis also suffered more rainfall than in the Côte d’Or. For example, BIVB statistics show that in May 236mm fell in Chablis, as compared to 139mm in Beaune and just 126mm in Mâcon. In fact, 85% of the rainfall in Chablis fell in the first six months. This made it difficult to find dry windows to spray and protect the vines from mildew. Sunlight hours were also up to 40% lower than average between February and June.

Then the weather changed volte-face. July and August enjoyed average sunlight hours and September temperatures were 15% higher than normal. This was the saving grace for 2016, since it allowed the bunches to reach full maturity, albeit later than usual. That said, being later in the season the sunlight hours are shorter and so the longer you have to wait, the less beneficial a clement day will be. Sugar accumulation in the final week of August was around 3.9gm/L per day, falling to 1.5gm/L by mid-September. In the end the maturity level was said to be not dissimilar to 2011.

The 2017 Growing Season

Two thousand and seventeen began with a cold January, but then February and March were abnormally warm. It was a false dawn. From 18 to 29 April, a biting cold period settled all over France, putting Chablis in the direct firing line of frost. It took a direct hit. Again. According to the BIVB, the hardest hit sector were those vineyards located in the north: Maligny, Lignorelles, Ligny-Le-Chatel, Villy and La Chapelle-Vaupelteigne. “Like everyone, we had frost damage in 2017,” Isabelle Raveneau rued. “It lasted about a week and the temperature was low and the humidity made it worse. If it is just one or two nights then it doesn’t do too much damage. It was problematic in the Grand Crus and in Montée de Tonnerre, basically everything on the Right Bank – different areas to 2016. For example, in 2017 Valmur was badly damaged but in 2016, not at all. The 2016 was more like a winter frost and 2017 more like a spring frost.” Patrick Piuze lamented the 11 consecutive days of frost that at its worst plummeted to -7° Celsius, depriving him of some of his regular labels (though fortunately supplemented by others.)

Isabelle Raveneau inspecting her samples of 2016 Chablis

Thereafter, unlike the previous year, the growing season was less traumatic. Sunlight hours were around 10% above average in May, June and July. Mi-fleuraison was on 5 June, much earlier than in 2016. Sugar accumulation was steady but very gradual. In terms of precipitation, most growers spoke of getting a splash of rain just when they needed it. By the time of harvest, most vineyards were in healthy sanitary condition. All that was missing was the quantity due to the frost; some parcels were 80% to 85% down compared to a regular millésime. The one critical difference that distinguishes 2017 from 2016, a difference mentioned by Isabelle Raveneau, is that 2017 hit the Grand Crus heavily as well as “Right Bank” Premier Cru vineyards, those north and east of the Serein such as Montée de Tonnerre, Montmains inter alia. Whereas in 2016 you could argue that frost hit the quantity of Chablis, that is to say, mostly the Village Crus, the following year Mother Nature turned her ire upon the more valuable, propitious vines. Had it only been one or two nights of frost, then winemakers might have been able to cope and militate against damage, but the protracted nature meant that quantities were unavoidably affected. It was a relatively early vintage with many growers picking up their secateurs (or turning the ignition on their machines) around 4 or 5 September, some three weeks earlier than the previous year. This graced them with a less time-pressured, almost “leisurely” harvest that really benefits those who pick by hand, since they need that window to organize picking teams and laboriously work they way through the vines. Coupled with the depleted quantities, perhaps the one silver lining was that there was less to pick and so growers could be even more meticulous if they wished.

Patrick Piuze, a winemaker who opted to forge enviable fruit contracts rather than acquire vineyard holdings, a strategy that has worked extremely well in recent years

Hail! Hail! Hail Nets

Looking upon Grand Cru Les Clos on one morning, I noticed an incongruous patch of vines covered in grey-ish colored material and so I traipsed up to investigate... Hail nets. Enfin! A quick perusal of recent growing season summaries makes it clear that hail has become not some random meteorological hazard, one whereby any loss is simply something growers must take on the chin. It has become a potential catastrophe that must be anticipated every season. Such is the localized and spontaneous nature of hail that it is impossible for growers to do anything but look on as spectators to destruction, unlike frost, where at least you can pre-emptively distribute candles or spray moisture onto the vines. So why were they forbidden? Firstly, because there is no doubting they are a bit of an eyesore. More importantly though, some suggest that it interferes with the mesoclimate: shading the vines and retarding the vegetative cycle. Such has been the damage in recent years that the authorities experimented on 30-hectares of vine and concluded that anti-hail nets did not interfere with the mesoclimate of the vine. On 20 June the INAO finally authorized their use. This has massive implications for a hail-prone area like Chablis and at least gives growers an effective weapon to protect their vines if the forecast shows a threat to both vines and livelihoods. Plus, it would not surprise me that as technology advances, they will become perhaps thinner and more transparent.

Vincent Dauvissat at his domaine in Chablis

Premier Versus Grand Cru

I am going to put this contentious debate out there...

There is a debate that questions the inherent superiority of Grand Crus over Premier Crus in Chablis. It might be sacrilegious after all, thou shalt not speak against the classification! However, I know a number of experienced mavens who forego Grand Crus and delight in the vast range of Premier Crus that they see as the apotheosis of Chablis terroir. There is a sound argument for that case. Firstly, if one takes the view that true Chablis eschews ageing in barrel, then growers’ propensity to employ oak for their Grand Crus and mature their Premier Crus in stainless steel means that the latter adheres more to what Chablis ought to be – unfettered by winemaking/human intervention, to wit, a mirror-image of the soil. Secondly, you could argue that with global warming, the more exposed Grand Crus will reach maturity quicker than Premier Crus and therefore the latter may enjoy a longer hang-time that engenders greater complexity. Of course, this is countered by the fact that we are talking about a marginal climate. A cursory glance at my own scores will reveal that I have no hesitation in awarding more favorable reviews and attendant scores to Premier Crus over Grand Crus if I find it merited. When you factor in prices then perhaps the best Premier Crus such as Montée de Tonnerre and Montmains represent Chablis’ choicest cuts?

Benoît Droin, surely one of the most impressive winemakers in Chablis at the moment

Cooperative Versus Artisan Grower…

The word I dislike in the above sub-heading is “versus” since I like to think it is not a case of one or the other. In the past, Chablis leaned heavily towards large-scale cooperatives that rather undermined its reputation as further south, the Côte d’Or spawned more and more individual domaines with personalities at their helm. It made Chablis a bit...faceless? That is certainly changing. It is by no means a revolution, however, there are certainly more and more growers venturing out on their own, allowing contracts with cooperatives to expire and gain autonomy over how they approach their winemaking. Even during my visit, several winemakers commented how the largest cooperative, La Chablisienne, will lose some 200-odd hectares of prime vineyard in forthcoming months due to expiring contracts.

I want to retain some balance here. I certainly want to see more and more winemakers go it alone because that encourages better wine. You cannot simply rely on the pre-agreed price with the cooperative and wait for the machines to arrive and pick your grapes. Chablis needs more personalities and in particular, it needs younger personalities. They are the lifeblood and the future of any wine region. The reality can be different. As one vigneron told me, whilst they have fulfilled their dream of establishing their own winery, farming their own vines how they see fit, the romance of this vocation is tempered by the realities: constant fear of hail and frost, dealing with diseases such as Esca, the drudgery of administrative work (bills of lading, dealing with importers and not least, France’s penchant for bureaucracy and paperwork.) Ultimately I believe very few regret realizing their dream, but it is not easy and not a guaranteed success. Furthermore, I will happily defend cooperatives and especially La Chablisienne. Sure, they might represent the antithesis of the artisan winemaker with dirt under their fingernails. But the truth is that when I totted up the result of my blind tasting, I was impressed how well their wines performed in their various categories.

At the end of the day, Chablis needs to reach equilibrium between individual growers and cooperatives. Do not assume that a cooperative cannot potentially make better Chablis than an individual grower. If you hold that view then you are blindsided by the romanticism of wine rather than the reality in the glass. An individual grower can make decisions that make their wine distinctive and unique, particularly in terms of viticulture and Chablis has seen a rise in organic and biodynamic winemakers such as Thomas Pico and Alice and Olivier de Moor. If you read their entries below, you will also see the risk of their approach, in my opinion, a risk worth taking when judging the quality of their wines, at least when not victims to frost and hail. Conversely, cooperatives provide the reach. Most consumers will not know Chablis through Raveneau or de Moor or Samuel Billaud. They will judge Chablis by a bottle they pick up at the supermarket and so it is imperative that cooperatives maintain a level of quality that upholds its name.

It is always a pleasure to visit with Laurent Tribut and taste through the wines

Cork Versus Alternative Closure

The truth is that only a small percentage of Chablis is cellared and even the greatest names are difficult to resist in their youth (a crying shame since Vincent Dauvissat’s wines regularly require several years in bottle.) If much of Chablis is being consumed in its youth, and for the record I have absolutely nothing against that, then why not obviate the danger of TCA by using alternative closures such as ScrewCap or Diam. Certainly growers, most notably Benoît Droin, now bottle their entire range under Diam. Tasting his wines blind against others every year, I see absolutely no influence using an alternative to cork. And frankly, I am waiting to be convinced that there is a difference after cellaring bottles long-term. Hopefully we will see more growers moving towards alternative closures, even ScrewCap for entry-level wines, because the stigma surrounding their use is declining and, at the end of the day, it is always the consumer that suffers a corked bottle. Certainly the stigma towards alternatives to cork are decreasing and likewise consumer resistance depending on country. I asked Toby Morrhall, buyer at “The Wine Society” and a major purchaser of quality Chablis about the UK market. “We have had no resistance to Diam. We have the 2007 vintage of William Fevre’s Premier Cru Vaulorent under Diam 5 and its in excellent condition. If you adjust the free sulphur you can avoid reduction whether using Diam 5, 10 or 30.” This is an important point. Certainly throughout my tastings at the BIVB, I encountered a number of wines that were suppressed by what felt like fixed sulphur that no amount of aeration will dislodge, and there are times when that can be attributed to a misjudgment of using SO2 under alternative closures.

Fabien Moreau, looking quite happy considering that I overlooked booking an appointment at the Domaine

The Wines

Chablis has been battered by recent vintages, but not broken. However, the ineluctable truth is that the growing seasons will influence wines for the reasons that I set out in my introduction. The pair of vintages under question in this report comes after a rather “middling” 2013 vintage, followed by a benchmark 2014 and a 2015 that is good but perhaps a little too ripe for those seeking “real” Chablis.

Generally speaking, I find the 2017 vintage to hold more promise than the 2016. The frost and hail impacted the quality of the resulting fruit – that cannot be denied. What also cannot be denied are the herculean efforts the winemakers made in overcoming hurdles thrown in their way. I know that many winemakers in conversation are quite positive about the 2016 vintage; several commenting that there was a hidden mineralité that revealed itself only after the wines began their ageing in barrel. But that is more a case of their initial pessimism turning into relief. When intensively tasting through 2016 and 2017, I discern more brightness and clarity in the latter while producers rather put the previous vintage into sharp relief.

I wrote before that the 2016 vintage was difficult to fathom from barrel. Now that I have tasted the wines in bottle, I feel that the traumas of frost and hail were just so severe in the early part of the growing season that the splendid July and August, coupled with the efforts of winemakers in the vineyard, helped avoid what would have otherwise been a disastrous vintage. It is as if the impact early in the season expended the vines’ energy – like running an 800-metre race where somebody throws hurdles on the first lap. The second lap becomes much more difficult – your reserves are sapped. That said, in 2016 some growers did manage to exploit the final clement days in September to reach full ripeness levels therefore it is a season where you really want to hone in on the best growers. Compare that with 2017, where several growers described the harvest as stress-free, like in 2014, and that makes a difference. Sure, there are some particular vineyards that are a step behind others depending upon grower. It is not a vintage that offered every producer a royal flush of great Chablis, but overall it is a vintage that may end up being the best since 2014.

You Might Also Enjoy

Burgundy Under the Radar, Neal Martin, July 2017

Red Burgundy 2016 and 2015: Two Terrific but Very Different Vintages, Stephen Tanzer, January 2018

Chablis 2016 & 2015: Quality Over Quantity, Stephen Tanzer, August 2017

The Undiscovered Burgundy, Antonio Galloni, June 2017

The 2014 White Burgundies: What’s Not To Like?, Stephen Tanzer, September 2016

The 2015 White Burgundies: A Year of Sunshine, Stephen Tanzer, September 2016

Chablis Gets the Côte de Beaune Treatment from Mother Nature, Stephen Tanzer, July 2016

Show all the wines (sorted by score)

- Albert Bichot (Domaine Long-Dépaquit)

- Céline & Frédéric Gueguen

- Domaine Alain Besson

- Domaine Alain et Cyril Gautheron

- Domaine Alain Mathias

- Domaine Alice et Olivier De Moor

- Domaine Barat

- Domaine Beaufumé

- Domaine Bernard Defaix

- Domaine Billaud-Simon

- Domaine Chanson

- Domaine Charly Nicolle

- Domaine Christian Moreau Père et Fils

- Domaine Christophe Ferrari

- Domaine Clotilde Davenne

- Domaine Daniel Dampt/Jean Defaix

- Domaine de Mauperthuis

- Domaine Denis Pommier

- Domaine Des Marronniers

- Domaine des Miles

- Domaine de Vauroux

- Domaine Di-Blas Frères

- Domaine Dominique Gruhier

- Domaine Drouhin-Vaudon

- Domaine du Chardonnay (Etienne Boileau)

- Domaine du Château de Fleys

- Domaine Duplessis

- Domaine Edmond Chalmeau & Fils

- Domaine Eleni & Edouard Vocoret

- Domaine Fourrey

- Domaine François Raveneau

- Domaine Gilbert Picq

- Domaine Guy Robin et Fils

- Domaine Jean-Claude Courtault

- Domaine Jean Collet et Fils

- Domaine Jean Dauvissat Père et Fils

- Domaine Jean-Marc Brocard

- Domaine Jean-Paul & Benoît Droin

- Domaine Jolly et Fils

- Domaine Laroche

- Domaine Laurent Tribut

- Domaine L&C Poitout

- Domaine/Maison Louis Jadot

- Domaine Millet Père et Fil

- Domaine Nathalie et Gilles Fevre

- Domaine Pattes Loup

- Domaine Roland Lavantureux

- Domaine Samuel Billaud

- Domaine Sébastien Dampt

- Domaine Seguinot-Bordet

- Domaine Servin

- Domaine Solange Tribut

- Domaine Sylvain Mosnier

- Domaine Ternynck

- Domaine Verret

- Domaine Vincent Dampt

- Domaine Vincent Dauvissat

- Domaine Vrignaud

- Domaine William Fèvre

- Jean Moreau et Fils

- La Chablisienne

- Les 7 Lieux - Julien Brocard

- Le Vendangeur Masqué (Alice et Olivier de Moor)

- Louis Michel et Fils

- Louis Moreau

- Maison Mathias

- Maison Olivier Tricon

- Maison Stéphane Brocard

- Marsoif SCEA

- Mauperthuis

- Olivier Leflaive Frères

- Pascal Bouchard

- Patrick Piuze

- Simonnet-Febvre

- Stéphanie & Vincent Michelet