Browse using the new Vinous website now. Launch →

Printed by, and for the sole use of . All rights reserved © 2015 Vinous Media

Burgundy With (Plenty Of) Age: 1865-1999

BY NEAL MARTIN | MAY 14, 2019

“No one that has drunk old wine wants new; for he says, “The old is nice” – Luke 5:39

Four Bottles That Taught Me

The first part of this article examined vintages that many Burgundy-lovers will be enjoying at the moment, either in restaurants or at home, or perhaps at organized merchant tastings or off-lines. Hopefully you excused my loose definition of "mature" in the expectation that this second part would broach bottles with plenty of age. You want hand-blown bottles with wonky necks mummified in thick crusts of dust and mold; bottles that have seen history; bottles that are history. This article takes a rare journey back through nearly every decade to 1865. It is a one-off article, since I have never spent so long accumulating observations in dog-eared, Pinot-splattered notebooks, the backs of folded-up menus and my beat-up laptop. Trust me when I say that I have no intention of repeating the exercise.

There is no theme except region, age and wonderment.

Friday night Burgundy when a friend visited from Hong Kong in early January.

Before I go on, allow me to recount four bottles that were catalysts for my appreciation and understanding of mature Burgundy. The first was a 1937 Richebourg from Bouchard Père & Fils. Until then, I had been indoctrinated by Bordeaux and naively assumed it constituted the zenith of wine. That Richebourg, served over lunch in an oak-paneled dining room in St. James’s Street, opened my senses to the longevity and profundity of mature Pinot Noir and revealed the heights it could achieve. Sadly, I lost the tasting note. Second is a 1962 Grands Echézeaux from Domaine de la Romanée-Conti, from a bottle whose tatty label and alarming low ullage had discounted it into the realm of affordability. A computer-literate friend, who used to help code my fledgling website for remuneration in fine wine, came for dinner. Forewarning him that it was likely oxidized, but with nothing to lose, I delicately prized out the cork. Fragrant Pinot Noir filled my small kitchen. Time stopped. It was one of the most ethereal Burgundy wines I have ever tasted, and we still wax lyrical about it whenever we meet. Third is the 1990 Nuits Saint-Georges Clos de l’Arlot from Domaine de l’Arlot. It was my first trip to the region, in 1997, and I ordered it at Beaune institution Ma Cuisine. Like the aforementioned Richebourg, it articulated the beauty and purity of Pinot Noir and taught me that greatness was not exclusive to ancient bottles or Grand Crus. The Burgundy hierarchy is useful, but it is not the final word on quality. Case in point: the fourth illuminating bottle, a 1992 Grands Echézeaux from Domaine de la Romanée-Conti, opened for an old school friend chez moi. It was preceded by all the pomp and ceremony I could muster, and I poured the bottle in hushed reverence... It was rubbish. Distastefully green and stalky, it was drinkable but certainly not pleasurable. I learned that even the most hallowed domaines and vineyards are no guarantee of greatness. Nobody is infallible.

Since those four game-changing bottles, I have been fortunate to taste more than my fair share of mature Burgundy. I am thankful that the early days of my career and my burgeoning interest overlapped with what I call the “twilight of affordability.” In the late 1990s, I regularly bought bottles from Sylvain Cathiard, Denis Bachelet, Jean Grivot, René Engel and even Armand Rousseau as part of my education. They were not too expensive and easily accessible. I vividly recall opening Rousseau’s 1996 Chambertin with my cousin to accompany my tomato pasta, not because I wanted to impress, but simply because she fancied a red and I thought it would be nice; I could always buy another. Burgundy was for those who could ill afford Bordeaux, a niche, cultish wine for nerds who could recite the five owners of Clos Saint-Jacques. In retrospect, those were innocent times, and I miss them. The turning point was 2005. This vintage alerted a wider audience to Burgundy. Gatecrashing the party of Burgundy anoraks was an influx of oenophiles, some with genuine passions but many who latched onto the rarity and collectibility of the top growers. The chase was on to secure allocations of coveted and elusive cuvées. Consequently it has become almost impossible to open a mature Burgundy without being cognizant of its value and irreplaceability. What would it cost to replicate a tasting of the 200-odd wines in this report alone? In fact, it’s probably impossible at any price, since some bottles may well represent the last survivors. Yet it’s worth remembering that a vast majority were sold cheaply at the time – unlike these days, when more and more growers conscientiously position their new releases at price points designed to demonstrate that the contents are worth it. Sometimes they are; sometimes they aren’t. I guess that is the raison d’être of this article.

Grivot’s 1990 was the oldest bottle at a fascinating Clos Vougeot tasting last year.

How Do You Like It?

In Part One, I dwelled upon the mercurial nature of mature Burgundy and the challenge of recommending drinking windows.

Another variable is you. How do you like your wine?

Do you revel in primary fruit and tannin, body and grip? Or do you prefer the ritual of cellaring bottles to savor secondary aromas and flavors, to plot their evolution, to nurture your precious babies into adulthood and their dotage? Some weird Burgundy aficionados even have a penchant for exhuming bottles from the grave, and given some of the wines in this report, I must plead guilty. I acknowledge that there are many whose palates are not attuned to maturity. I often hear the comment, “I just don’t understand what people see in old wine.” I get that. Mature wine is less immediate for the banal reason that it is endowed with less fruit, less inclined to trigger the senses and frequently more difficult to understand. Young, fruit-driven wine is like reading a page-turning novella. Mature wine is like reading Dostoevsky... in Russian. You scratch your head, wondering what all the fuss is about, perplexed by others’ fixation with vinous necrophilia.

My argument is this: Surely, time must be allowed to gently sculpt fine wine.

No human intervention or winemaking technique can replicate the mysterious and enhancing effects of time. A majority of wine-lovers’ most magical experiences are the rewards of cellaring for the appropriate duration. Age does not vouchsafe quality; indeed, you might have missed the moment when a wine was at its zenith. But when you do encounter that tantalizing nexus of age and beauty, it can be an unforgettable transcendental experience, preferably one that is shared. Speaking for myself, as I hope I communicated in Part One, I have no qualms about cracking open a fine bottle when it has barely learned to walk. Pinot Noir is generally an approachable variety and, with few exceptions, does not obstruct enjoyment with unyielding tannins that need years to soften. However, nothing quite compares to a great bottle of Burgundy when it reaches an ethereal plain and manifests a kaleidoscope of secondary aromas and flavors. The way it can defy time and evolve such profound nuance and complexity is as remarkable as it is enigmatic.

The bouquet of this 1986 Richebourg direct from the cellars of Méo-Camuzet was ethereal. Henri Jayer made this wine.

A Different Landscape

The problem with Burgundy is that up until the 1990s, the number of quality-focused growers was small. Burgundy has always been well regarded thanks to its long history, yet it lacked the esteem and international renown of Bordeaux, not least because there simply was not the same quantity to establish reputations. As André Simon pointed out in his indispensible Vintagewise back in 1945, Bordeaux’s reputation was consolidated by trade links between the Gironde and Thames estuaries, whereas landlocked Burgundy was more difficult to access for all except the Low Countries. Even well-known growers and vineyards struggled to fetch a premium for their wines, and the region was hit hard during times of economic malaise. As already mentioned in my recent article, in the 1930s even Domaine de la Romanée-Conti had to be subsidized by the family’s farm in Moulins-sur-Alliers. Of course, there were pioneers who dedicated their lives to producing the best-quality wine possible. Off the top of my head, that roll call includes Henri Jayer, Lalou Bize-Leroy, François Raveneau, Jacques Seysses, Henri Gouges, Gérard Potel, Jean-François Coche, Dominique Lafon, Charles Rousseau, René and Philippe Engel, the Marquis d’Angerville, Georges and Christophe Roumier, Alain Roumier (régisseur at de Vogüé until 1986), Michel Lafarge and Pierre Ramonet. They were all trailblazers in the sense of aspiration, dedication and talent. But they still constitute a small number of growers and wines, so it’s no wonder demand focuses on this select group and renders their prices prohibitively expensive.

There is a counter-argument, one germane to this article and the reviews within. Historically, the industry was dominated by Beaune-based négociants/merchants. Their wines do not attract the same fevered demand as family-run domaines, partly because the notion of a corporate-run enterprise is less romantic. However, their wines can be just as good if not better than those of small domaines. One example in this report is the ethereal 1949 Chambertin from Bouchard Père & Fils, which is as profound as any Rousseau or Roumier I have tasted. Producers like Joseph Drouhin have long been ostensibly family-run enterprises that farm their own vines, many in some of the choicest locations in the Côte d’Or. It is not an “us and them” scenario.

One of the bottles from Louis Jadot’s cellar that was opened on a memorable night.

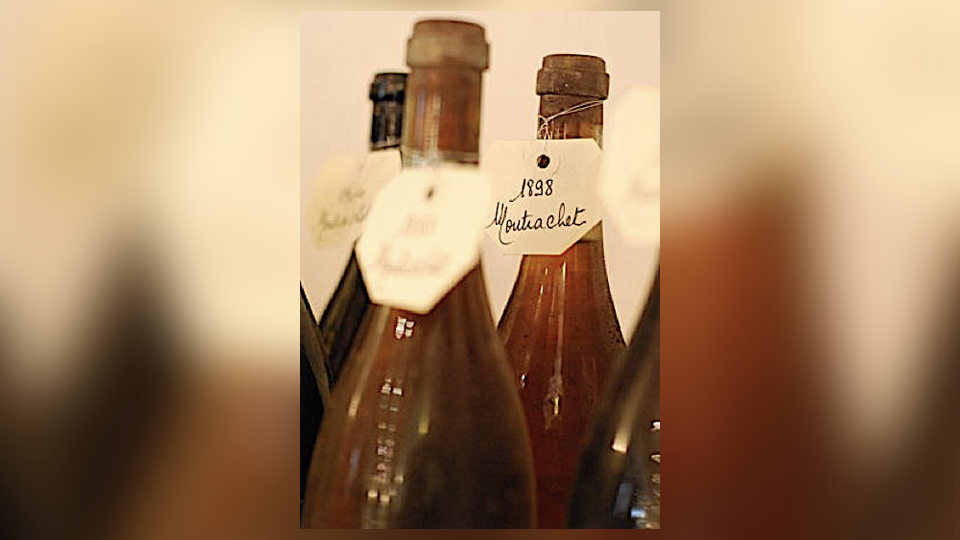

For this reason you will find a number of tasting notes from Louis Jadot’s 150th anniversary tasting that I recovered after mislaying them for many years. These include some of the oldest Burgundy wines I have tasted, including the 1865 Corton and the 1898 Montrachet. Of course, many small négociants proliferated across the region, and one of those was Seguin Manuel. The name disappeared until Thibaut Marion resurrected the name about a decade ago. To finance the deal, Marion auctioned a treasure trove of ancient bottles through Christie’s auction house. A few of my friends successfully bid for them and duly organized a tasting in London, with Marion in attendance. It turned out to be one of the most memorable tastings I have attended, and proof that with impeccable provenance, bottles from unfamiliar or unheard-of producers can provide remarkable experiences. Like the notes for Jadot, these notes were lost for many years and I resolved to recover them and publish them here. (Readers should note that I continue to cover Seguin Manuel's wines, and they often represent great value and quality.)

Don’t Fear Low Levels

One point I would like to make with regard to mature bottles of Burgundy: Don’t be frightened by low levels and don’t reject them out of hand. In my view, the shape of the Burgundy bottle exaggerates evaporation vis-à-vis Bordeaux, so that the level simply looks disconcertingly lower. Personally, I eschew bottles that have been topped up, even at the domaine, and would choose a Burgundy with its original cork and a low level over the same wine reconditioned. I find that topping up often discombobulates the wine, notwithstanding that the cork could be infected with TCA or simply not inserted properly. The most important determinant is clarity. Hold the bottle up to a light; if the contents look clear and without excessive browning, then I find that a majority, even those from less reputed vintages and/or vineyards, can provide a lot of drinking pleasure. A good example of this is the 1972 Chassagne-Montrachet Clos Saint-Jean Rouge from Château de Maltroye. I picked it up from a retailer in Beaune for 30 euros. What’s that worth? The price of a recently released Bourgogne Rouge? While no contender for “Wine of the Year,” it was delicious. You will find bottles in this report that were re-corked and performed extremely well, including some of those aforementioned ancient Jadot bottles, so of course there are exceptions. But generally I have had more positive experiences with bottles that have not undergone reconditioning.

The Wines

A vast number of tasting notes come from two private La Paulées in Beaune. I have attended this annual gathering of friends from both sides of the Atlantic for a number of years, and it never ceases to provide an array of remarkable bottles amid the bonhomie and chansons de boire. The wine selection tends to be esoteric insofar as it is not an endless run of large-format DRCs and Leroys, but rather a smorgasbord of fascinating growers and vintages. You never know what’s coming next. I never take notes on every wine, only those worth reflecting upon. La Paulée is always one of my highlights of the year but also one of the hardest tastings, a six-hour span during which I will fill up half my notebook with observations.

Bottles waiting to be opened at La Paulée.

This report also includes tasting notes that are simply gathering dust. They could probably be marshaled into separate articles, but I would be resigned to forever playing catch-up. In particular, the notes include the older vintages of Clos Vougeot from the tasting at Château du Clos du Vougeot in March 2018 (the younger vintages are covered in Part One) and a memorable dinner in Hong Kong that focused on mature white Burgundy without a single instance of premature oxidation, dinners at the 1243 Society in Beaune during Hospices week, bottles from my own cellar acquired when they were affordable…

There are over 200 mature Burgundies in this report. It would be remiss of me not to single out some of them.

A 1977 Corton-Charlemagne from Bonneau du Martray was my offering for La Paulée last November. The bottle’s clarity made it a risk worth taking, since it was born in one of the most derided vintages ever. And it turned out to be a gem. Off-vintages are often less expensive and, in my experience, less traded between merchants and therefore come with better provenance. Here you will find examples from excoriated vintages such as 1940, 1946 and 1956 that all had something to offer.

The 1973 Montrachet Grand Cru from Domaine Fleurot-Larose is an exercise in knowing your origins. Growing season, age and winemaking regimen at the time conspired to make this an ordinary Montrachet, enjoyable but frankly over the hill. So why bother? Well, this tiny 0.04-hectare parcel was acquired by Anne-Claude Leflaive in 1991 and became her elusive jewel. Hunting bottles like this is exactly the same as what vinyl junkies call “crate digging,” flicking through boxes of secondhand records in the hope of discovering a rare and coveted gem. The composition of Burgundy today is the result of countless divisions and amalgamations of domaines’ holdings governed by economic necessity, primogeniture, marriage and divorce. The region might appear unchanging but it is constantly shape-shifting in terms of ownership. Discovering how domaines built up their present holdings is a fascinating exercise, often revealing forgotten names subsequently erased from history. Perhaps the most famous is Charles Noëllat, whose vineyards became Domaine Leroy in 1988. Some are forgotten for good reason – they made awful wine – but even these bottles can lend insight, allowing you to drink a wine from the same parcel of vines farmed by a different winemaker, and often they can be cheaper because they are not investor catnip.

The 1980 Chambolle-Musigny Les Amoureuses was not the pinnacle of that great vineyard, but it prompted me to ask the question: Who made it? You very rarely see bottles from this era, so I assumed that a proportion of the production was sold off. In the early 1980s, Frédéric Mugnier was flying his Fokkers (sorry, I couldn’t resist writing that) for TAT airlines before his career change in 1988. Digging around, I eventually discovered that Bernard Clair, father of Bruno Clair in Marsannay, oversaw the wines during this period. It is always fascinating how old bottles reveal connections that would otherwise remain hidden.

The 1937 Chablis Fourchaume from Domaine Simmonet-Febvre is the oldest Chablis I have encountered. It was made during a very difficult period for the region, which was suffering a rural exodus of workers to Paris and the consequent abandonment of vineyards. After World War II, there was less than 500 hectares under vine. It was a pleasure to find that after so many years, this Chablis continues to give pleasure. This bottle was a rare thread connecting Chablis’s halcyon days in the 19th century to its current prosperity, a thread that ensured its survival as a wine-producing region. And it was still delightful. Bottles like this should be saluted.

This Montrachet was a precursor to Domaine Leflaive’s crown jewel.

The prize for the strangest wine in this roundup must surely go to the 1949 Puligny-Montrachet Clos de Cailleret 1er Cru Rouge from Domaine Chartron poured at a lunch with friends in Hong Kong. Yes, that’s correct: red Puligny. In fact, this cuvée continues to be made by Jean-Michel Chartron, although the quantity is only a barrel or two. It’s a reminder that as you go back through decades, the composition of vineyards was different. At one point, there were parts of Montrachet planted with red varieties and, who knows, maybe with Gamay instead of Pinot Noir. Unfortunately, this 1949 was pretty shot; however, I kept the note without a score to record its existence.

The 1928 Pommard from Domaine Leroy is a rara avis generously poured by a Belgian Burgundy-lover. Prior to Lalou Bize-Leroy’s acquisition of Charles Noëllat, Leroy was a highly successful négociant built up by Lalou’s father, Henri Leroy. Unlike his daughter, he comes across as more a mercantile man than a vigneron, and though I’m sure he was invited to purchase vines in the 1930s, he preferred to contract with growers to provide fruit for Maison Leroy. Only the very best would tempt him to buy land, which led to his 50% acquisition of Domaine de la Romanée-Conti. However, he did own a small patch of vines in Pommard, which is where this bottle originates. It came in a remarkable squat-shaped bottle and, to be honest, none of us were expecting much. Yet it was an ethereal Pommard, fragrant on the nose and showing vestiges of red fruit on the palate.

I single out the 1945 Charmes-Chambertin from Grivelet as an example of the dubious practices followed in Burgundy back in the day. Bernard Grivelet was one of the most notorious, and makes Rudy Kurniawan seem innocent. In 1979, Grivelet was indicted for mislabeling wines for the American market; he already had a record, having been jailed during World War II for selling wine to the occupying German army. Was this 1945 the real thing? Well, it was pretty unremarkable given vintage and vineyard. Who can tell after so much time has passed? I also had my doubts about a 1946 Charmes-Chambertin from Labouré-Roi that seemed pepped up with something beyond the Burgundy boundary. The shady background is always worth bearing in mind if you see bottles come up for auction. (As an aside, I recommend the recently published tome from Allen Meadows and Doug Barzeley entitled Burgundy Vintages, which offers plenty of useful information on counterfeit bottles or those suspected of being doctored.)

At the other end of the spectrum from Grivelet is winemaker René Engel, the professor of oenology at Dijon University who crusaded for legislation to guarantee that what’s stated on the label is really what’s inside the bottle. I have been fortunate to taste a number of bottles from the domaine, and in both Part One and Part Two of this Burgundy article, you will find several notes predating the untimely passing of Philippe Engel in 2005. The 1947 Grands Echézeaux is one of the oldest bottles from the domaine and would have been made by René Engel, who retired in 1949. It encapsulates everything that is so profound about mature Burgundy, and decades later it continues to glisten like a pearl in the sand.

The 1993 vintage is now fondly regarded, though that was not always the case and one or two commentators lambasted the vintage on release. The 1993s typify the unpredictable nature of Burgundy; they did not blossom for many years and were largely forgotten about. I include a dozen or so tasting notes, including the top three from Armand Rousseau that I was lucky enough to taste side by side. Antonio Galloni rightly feted the Clos-de-Bèze in his Ten Wines That Changed My Life article last year, and to be honest, there is only a cigarette paper between the three in terms of quality. Nineteen-ninety three is a vintage that consistently shines brightly in vertical tastings, and I have been lucky to taste a few bottles with friends at dinners and off-lines. They are becoming difficult to track down these days. Conversely, the 1996s continue to leave their early promise unfulfilled. Is it case of being more patient, or will those hard tannins and sultry personalities always make this a difficult vintage to love?

Mature white Burgundy is a tricky one. First and foremost, you have to play Russian roulette with post-1996 bottles afflicted by premature oxidation. The exact cause remains unknown, but years of denial did growers no favors, and some domaines’ reputations suffered as a result, along with the reputation of the entire white Burgundy category. (There are theories that premox is a passing phase and that if you leave affected wines long enough, they will eventually rectify. This is not a view that I concur with, and in any case, it would take a lot of hard-earned money to test this hypothesis.) Some bottles in this report rank among the finest white wines I have encountered anywhere in the world. The pertinent question is whether white Burgundy is worth cellaring long-term or whether you can derive as much pleasure by cracking it open young. Certainly, there are bottles such as the 1988 Bâtard-Montrachet from Pierre Morey and the 1989 Meursault Genevrières from Comtes-Lafon that were spellbinding and clearly offered great rewards for cellaring. But those rewards vary a great deal from bottle to bottle, and the whites that truly amaze are less prevalent than the reds. I guess what I want to say is that you should drink your white Burgundy whenever you want.

Personally, I always decant my white Burgundy, even with age. The consensus seems to be that the decanter should only be deployed for reds, but I find it is even more important to allow aged whites to breathe and settle. The 1971 Montrachet from Comtes-Lafon seemed lifeless for the first two hours, before its Damascene resurrection, and I have witnessed similar revivals many times. Even for younger bottles, decanting often allows the nuances to shine through.

You sometimes see old bottles from Grivelet, although they are always clouded by suspicion.

The Ethos of Sharing

Finally, not a single bottle among the 500 contained in Part One or Part Two was drunk in solitude. If I have no choice but to drink alone, I will make a cup of tea. Many of these bottles were enjoyed thanks to the generosity of friends around the world. The ethos of sharing is ingrained into Burgundy – ergo the tradition of La Paulée, the communal experience of taking a prized bottle and pouring it around the table, and the reciprocation. That ethos extends across the world, not least to Hong Kong, where so much mature Burgundy is now consumed. I can only speak about my own experiences and acquaintances, but it is unequivocally appreciated here as much as anywhere else, irrespective of cost or rarity. I would rather see such prized bottles shared and enjoyed than allowed to gather dust as totems of somebody’s wealth. I miss the time when my cellar was stocked with bottles of Grivot and Rousseau, which now lie beyond my financial means. Will the bubble burst? It is often predicted, but at this time I cannot see it happening. In any case, there are now plenty of alternatives to Burgundy, whether the Côte Chalonnaise, Hemel-en-Aarde or Martinborough. But nothing quite compares to a bottle of mature Burgundy in full flight.

See the Wines from Youngest to Oldest

You Might Also Enjoy

Burgundy With (A Bit of) Age: 2000-2014, Neal Martin, May 2019

Fermented Grape Juice: Romanée-Conti 1953-2005, Neal Martin, April 2019

This Is Not Morey-Saint-Denis, Neal Martin, March 2019

Bottles Never Forgotten - Burgundy Edition, Neal Martin, March 2019

Caught Somewhere in Time: Clos de Tart 1887-2016, Neal Martin, February 2019

The Picardy Third: 2016 Domaine de la Romanée-Conti In Bottle, Neal Martin, February 2019

2017 Burgundy: A Modern Classic, Neal Martin, January 2019

Ten Wines That Changed My Life, Antonio Galloni, May 2018

Show all the wines (sorted by score)

- Bouchard Père & Fils

- Château de la Maltroye

- Château de la Tour

- De Beauverand & De Poligny

- Domaine Alain Hudelot-Noëllat

- Domaine Armand Rousseau

- Domaine Armelle & Bernard Rion

- Domaine Blain-Gagnard

- Domaine Bonneau du Martray

- Domaine Boquenet

- Domaine Buisson-Battault

- Domaine Charles Mortet

- Domaine Chavy-Chouet

- Domaine Coche-Boulicault (Coche-Dury)

- Domaine Comte Armand

- Domaine Comte de Moucheron

- Domaine Comte Georges de Vogüé

- Domaine Confuron-Cotétidot

- Domaine d'Auvenay

- Domaine de la Bongran/Jean Thévenet

- Domaine de la Pousse d'Or

- Domaine de l'Arlot

- Domaine de la Romanée-Conti

- Domaine de Montille

- Domaine Denis Bachelet

- Domaine des Comtes Lafon

- Domaine Dubreuil-Fontaine

- Domaine du Comte Liger-Belair

- Domaine Dujac

- Domaine Etienne Sauzet

- Domaine Fleurot-Larose

- Domaine Fourrier

- Domaine François Gros

- Domaine François Lamarche

- Domaine François Morey

- Domaine François Raveneau

- Domaine Gabriel & Paul Jouard

- Domaine Georges Mugneret-Gibourg

- Domaine Georges Roumier

- Domaine Guy Roulot

- Domaine Henri Jayer

- Domaine Henri Noëllat

- Domaine Jacqueline Jayer

- Domaine Jacques Prieur

- Domaine Jean Chartron

- Domaine Jean-Claude Fourrier

- Domaine Jean-Claude Ramonet

- Domaine Jean-François Coche-Dury

- Domaine Jean Grivot

- Domaine Jean-Louis Trapet

- Domaine J-F Mugnier

- Domaine Joseph Voillot

- Domaine Leflaive

- Domaine Leroy

- Domaine Louis Carillon & Fils

- Domaine Louis Remy

- Domaine Marquis d'Angerville

- Domaine Maume

- Domaine Méo-Camuzet

- Domaine Mongeard-Mugneret

- Domaine Mugneret-Gibourg

- Domaine Passerotte-Battaut

- Domaine Pierre Morey

- Domaine Ponsot

- Domaine René Engel

- Domaine Robert Chevillon

- Domaine Rossignol-Cornu

- Domaine Rossignol-Trapet

- Doudet Naudin

- Grivelet Père & Fils

- Joseph Drouhin

- Jules Régnier

- Labouré-Roi

- Louis Jadot

- Louis Latour

- Louis Michel et Fils

- Louis Poirier

- Maison Boisseaux-Estivant

- Maison Champy

- Maison Leroy

- Morin Père & Fils

- Pierre Ponnelle

- Prince Florent de Mérode

- Remoissenet Père & Fils

- Seguin-Manuel

- Simonnet-Febvre

- Thomas-Bassot