Browse using the new Vinous website now. Launch →

Printed by, and for the sole use of . All rights reserved © 2015 Vinous Media

Priceless: Roumier Bonnes-Mares 1945 - 2015

BY NEAL MARTIN | SEPTEMBER 11, 2018

The elation that follows your firstborn child is entangled with trepidation, roiling emotions, fear of the unknown and a level of fatigue you never knew existed. You survive the first night on a couple of hours kip and then the following morning it hits you... You have to go through it all again... without the novelty...for eternity. Life. Is. (Insert expletive). Over. Only the euphoria of parenthood sees you through. I vividly recall our first night of normality when my daughter’s sleep serendipitously coincided with dinner. It must have been February 2005 when we were living in a rabbit hutch-cum-terraced flat in South London. I told my wife that this was the first and perhaps last time we could raise a toast to our addition towards the human race and it demanded a special bottle. Diving into the disused coalbunker where I kept my small but useful stash, I surfaced and decanted the wine. “I picked up a couple of these for £80,” I informed, sloshing Pinot into the carafe. “It’s a bit expensive. But Roumier’s 1985 Bonnes-Mares should be drinking nicely...”

Thirteen years later. That tiny bundle of joy is now a teenager. We moved out of the rabbit hutch. Christophe Roumier became a superstar. He has gone from a highly respected vigneron to poster boy for a new generation of aficionados that have swarmed towards the Côte d’Or, fuelling demand that outstrips supply by unthinkable multiples. I recall tasting the 2005 Musigny from barrel during which Christophe Roumier divulged that a recent visitor had implored him to sell the entire production of one and a quarter barrels. All Roumier had to do was name his price. Any price. It was a portent. I checked the market price of that 1985 Bonnes-Mares. Today it would set me back over £3,000 and in the time it has taken me to write this sentence, it has probably gone up even further. Indeed, all of Christophe Roumier’s wines cost not just an arm and a leg, but all your limbs and those of the person sitting next to you.

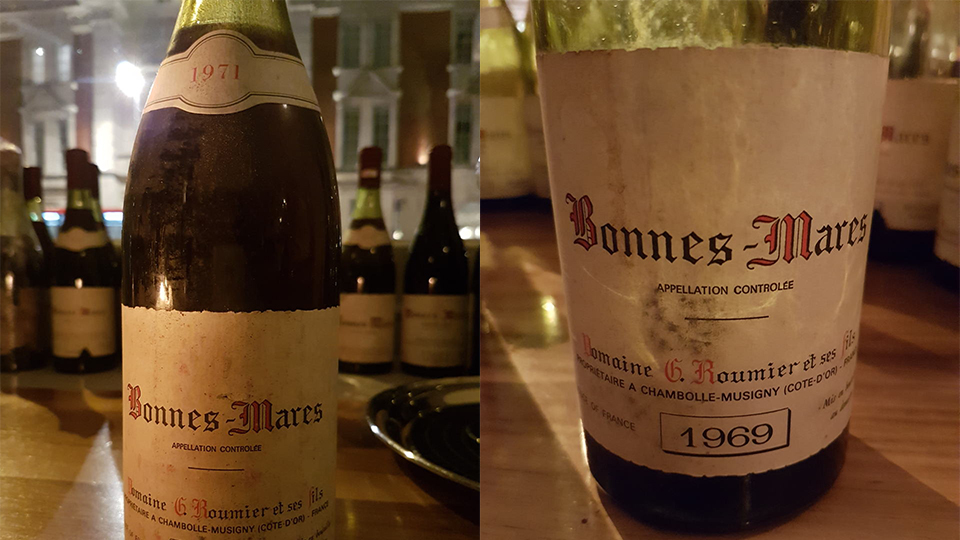

The Bonnes-Mares assembled at the London tasting

When a winemaker reaches status of a deity, as uncomfortably as that might fit someone as self-effacing and humble as Christophe Roumier, then too often their wines attain an unimpeachable air, their value inveigling wine-lovers and critics alike to overlook shortcomings. Sometimes it is vice versa and the chorus of approval becomes the bulwark against which to aim unfair criticism, to pull it down from its pedestal and preen about your recalcitrance.

This article seeks to take an objective look at the domaine and its wines, to adjudge where the wines deserve deification and where criticism is due. Do not expect high scores to rain down on everything that Roumier has touched. That does not reflect a winemaker who has been refreshingly critical of his own wines that articulate their respective terroirs and vagaries of growing seasons, warts ‘n all. It is built around one of the most comprehensive verticals of Bonnes-Mares you will ever read: more than 30 vintages spanning over 70 years and three generations of winemaking. The notes derive from two verticals, one in Hong Kong at the Mandarin Oriental Grill organized by the “crazy gang” of oenophiles. The other held in London, organized by Jordi Oriols-Gil last February, attended by Christophe Roumier himself. To whet your appetite, it includes a complete run of vintages from 1988 to 2002, the 1988 Bonnes-Mares and 1988 Vieilles Vignes juxtaposed not once but twice (both blind) with an explanation of their differences, a revisit of the aforementioned 1985, though this time comparing bottle against magnum, rare ancient vintages including two postwar gems from Roumier’s own reserve and one minor revelation. I add additional tasting notes including the 2002s tasted blind in Hong Kong and miscellaneous other notes culled from various recent dinners.

Basically this is the mother of Roumier articles.

So let’s set the scene and recount how Domaine Georges Roumier came to be.

History

Georges Roumier was born in Dun-Les-Places in 1898. In 1924 he married Geneviève Quanquin whose dowry contained vineyards in Chambolle-Musigny that included Bonnes-Mares. These crus were expanded via additional purchases, a métayage in Musigny and the Quanquin’s own independent négoçiant business. Crucially, he bought a third-share of Domaine Belorgey in 1952 that augmented another parcel in Bonnes-Mares, followed by two plots in Clos de Vougeot and the monopole of Clos de la Bussière in 1953. The Domaine was and still is located in the heart of Chambolle village next door to Frédéric Mugnier. The couple had five boys and two girls, which meant that even with the expanded vineyard there were no vacancies for all their brood and so the eldest son, Alain Roumier, began a successful tenure as régisseur at Comtes de Vogüé in 1955. Christophe Roumier told me that his own father, Georges’ third son Jean-Marie, began working at the Domaine around 1954/1955 (something to consider when you peruse my notes). Georges retired in 1961 and passed away four years later, upon which the siblings wisely formed a société civile in order to prevent the Domaine from splitting up.

Christophe Roumier in his barrel cellar in Chambolle-Musigny

Christophe Roumier was born in 1958. Like many of his contemporaries, he studied oenology at Dijon University and undertook a stage at the Carainne co-operative in 1980. Three years earlier in 1977 his father joined Charles Rousseau and Dr. Georges Mugneret in buying Ruchottes-Chambertin from Thomas-Bassot, the details of which you can find here in my account of Mugneret-Gibourg. Roumier’s involvement came via a métayage agreement with businessman Michel Bonnefond that continues to this day. The 0.10ha of Musigny was bought in 1978, the same plot the family has sharecropped since the 1920s. Only one pièce and one feuillette are normally produced, around 400 bottles, and although I have not tasted many vintages, Roumier himself admits that it can be inconsistent since he must accept whatever that barrel gives you. Imagine a vertical of Roumier’s Musigny. Could never happen, could it?

Christophe Roumier started working alongside his father Jean-Marie the following year although, like many father and son relationships, they did not agree on absolutely everything. Germane to this article is that Jean-Marie opted not to blend all the parcels in Bonnes-Mares into a single bottling, opting instead to produce a wine from terres rouges and one from terres blanches. This is new information to me and certainly timely, given that Roumier divulged this nugget of information just as we were tasting vintages from that era. With the exception of the 1959, we have no way of telling from which part of the Grand Cru it came from.

“I always wanted to blend the terres blanches and terres rouges together,” Roumier tells me. Up until 1988 the terres rouges went to [American importer] Château & Estate. However, there has never been any designation on the label. There is no way of telling which is which.”

Doubtless discretion was upheld to avoid importers demanding one or the other. It clarifies why Roumier chose to blend the two soils together in 1988 and divide by age of vine: to show his father that the marriage of the two soil types is more than a sum of its parts.

“The older vines are always picked later. In 1988 the younger vines had reached optimal ripeness in both terres blanches and terres rouges, but September was cool and the sugar accumulation slowed down. So, in this year I decided to treat the old and young vines separately and the older vines were picked some 10 days later but at the same yields, around 30hl/ha. There were three barrels of the Bonnes-Mares Vieilles Vignes [around 900 bottles]. The regular Bonnes-Mares was completely de-stemmed whilst the Vieilles Vignes included around 50% stems, though the rest of the élevage was the same.”

What are the differences between the two some 30-years later? Well, read on – the result might surprise you. What can be said is that from 1989 onwards, Roumier’s Bonnes-Mares comprised of all four parcels, terres blanches and terres rouges, though he keeps a few bottles of Vieilles Vignes and regular back for private purposes.

During the 1990s, Christophe Roumier became one of the most respected winemakers not just in Chambolle but in Burgundy. I have admired his wines from the beginning. He always comes across as one of the most affable and down-to-earth vignerons. Back in those days, his wines were not cheap but, as I mentioned, they were certainly affordable so that at one point a bottle of 1985 Bonnes-Mares and two bottles of the 1988 Bonnes-Mares Vieilles Vignes lay in my cellar (one, that turned out to be corked, exchanged for a vertical tasting and the other, some long-term Wine-Journal readers might remember, imbibed whilst listening to a marathon Led Zeppelin drum solo.

Christophe Roumier, here pictured by Johan Berglund way back in January 2007 when I tasted his 2005s from barrel; copyright Johan Berglund.

The turning point from Christophe Roumier was the 2005 vintage, as it was with many Burgundy winemakers. Then Roumier became one of the most sought-after winemakers. Secondary market prices subsequently reached stratospheric levels, something that Roumier sits uneasy with and as such, does his utmost to ensure that bottles are not simply flipped for quick returns. Today Roumier runs the Domaine with his sister Delphine and to be honest, he is just the same affable, sober man that he was when I first met him about 15 years ago. In terms of appearance he seems to have aged hardly a day, keeping trim with his passion for cycling and mountain walking. Approaching sixty he does not keep still, recently accepting a new challenge with a métayage shared with Arnaud Mortet in Echézeaux that debuted with a single barrel of 2017.

The Vineyard

I focus exclusively on the Bonnes-Mares vineyard here since it is the backbone of the notes and the domaine’s flagship label. The domaine owns 1.39 hectares of Bonnes-Mares, the third largest holding out of 22 proprietors after de Vogüé (2.7ha) and Drouhin-Laroze (1.49ha). There are four parcels: three located in the terres blanches on white marl that contains a larger quantity of fossilized oysters and one in terres rouges at the Morey end. When I asked Christophe Roumier the difference that each imparts, he told me that the terres rouges gives the power and concentration whilst the terres blanches gives the finesse and definition. The oldest vines date back to 1902.

The vineyard husbandry is close to organic although Christophe Roumier will use sprays as a last resort, and no chemicals with just occasional use of organic compost. The vines are pruned single-Guyot with a long “baguette” upon which half of the budding shoots are removed to enhance ventilation. He usually practices some de-leafing on the north side of the vines to again, maintain ventilation and improve anthocyanins. Although the vines are not selection massale, Roumier, having experimented without great success in 2000, instead aims for a maximum variety of clones. In his excellent Great Domaines of Burgundy, Charles Taylor MW points to a change from 113, 114 and 115 to clones such as 667, 777, 778 and 828 grafted onto 161-49 rootstock.

Of course, one of the key to success are the so-called “little steps in the vineyard”. Christophe Roumier spends a great deal of time amongst his vines. On a couple of occasions I have called in to visit and found him dressed in his work overalls – something you hardly ever see in Bordeaux.

Vinification

Christophe Roumier usually picks after others and tends to collect his older vines later, as he did in 1988 when he made two cuvées. He believes that there is less risk of over-maturity with older vines, whereas younger vines need more careful watching. The pickers do a selection in the vineyard, something I witnessed when chomping on a sandwich one year, only to find Roumier and his team pulling up to dispatch his vendangeurs into the vines. “The Bonnes-Mares takes one day to pick,” he explained at the London tasting. “We start in the morning. I chew the skins to check the ripeness but I don’t taste the pips. I will always pick before a rainy day is forecast.” The amount of stems used depends on the cru and the vintage and, to that end, I have recorded some figures of whole bunch percentages within the tasting notes. As a rule of thumb, the riper the vintage, the most stems Roumier uses and they normally come from the older rather than younger vines.

After a short pre-fermentation maceration at around 15° Celsius he does an initial pigeage followed by a gentle, long alcoholic fermentation for around 18 to 25 days in both epoxy-lined cement and stainless-steel tanks. “The way you extract the tannins is important,” Roumier emphasizes. During the process he gradually switches from pigeage to remontage to help oxygenate the wine and soften the tannins. Any vin de presse, if used, tops up the barrels. He is always prudent in his use of new oak, usually 20% for the village crus, 30% for the Premier Crus and around 40% to 50% for the Grand Crus. The wood is usually sourced from Vosges. He prefers a later malolactic fermentation. In order to have a spring conversion of the wines he keeps his cellar cool. He racks the wines the summer following the harvest. One thing to note with respect to the vertical of Bonnes-Mares is that he used to fine and filter the wines up until 1993, but not after that vintage.

The Wines

Although I include other tasting notes in this article, I focus on the vertical of Bonnes-Mares and broach the wines from youngest to oldest. (The Hong Kong tasting starts with four blind 2002s, that I am able to identify correctly only for Roumier’s ability to translate the character of each vineyard into the wine.) Also, I want to mention the 1999 Corton-Charlemagne that commences the London vertical in suitably audacious fashion. “I am impressed by the level of acidity,” Roumier remarks. “I was not expecting much when it was young, but I like the clean and pure fruit.” I completely agree – this is showing beautifully at the moment.

I usually narrate wines in chronological order but after much consideration, I am going to discuss the Bonnes-Mares from youngest to oldest.

The youngest vintage at the vertical is the 2007, however I have recently tasted three younger Bonnes-Mares that I include here. The standout is the electrifying 2012 Bonnes-Mares that is just so well-knit that you know there must be a master-craftsman behind its creation. It is going to be tempting to open these soon but wait a decade and you will have an exemplary Grand Cru on your hands. The 2011 Bonnes-Mares is a far more perplexing wine and has been variable on the three or four occasions it has cropped up, nicely structured but lacking the natural “flow” of the 2012. Is it just a gawky teenager? Time will tell. Better is the 2008 Bonnes-Mares with its almost peat-like bouquet mixed with earthenware and that trademark oyster shell-infused finish. You could probably start cracking these open now, though, personally, I would give it another 18 months or so.

The 2007 Bonnes-Mares is a great success considering that the wines were never supposed to age, words spoken by Christophe Roumier himself. It is a beautiful wine, not terribly complex when juxtaposed with others and yet it is equipped with disarming purity. The 2005 Bonnes-Mares, part of the astonishing Paris bacchanal that I recently wrote up, is denser and more extravagant than all the aforementioned vintages. Some growers dislike the rather rugged and forceful nature of this epochal season but this has wonderful incense aromas on the nose and a backward, structured and tightly-wound palate that has “long term” written all over it. The 2004 Bonnes-Mares is a perplexing wine. I always find the 2004 green and excessively herbaceous on the nose. Is this caused by the so-called “lady bugs” that infested the vats during fermentation? I just find this disjointed and herbal, missing Roumier’s usual flair. The 2002 Bonnes-Mares, from the Hong Kong vertical, is probably my favourite of the decade, utterly refined with filigree tannin and astonishing tension. It is a typical 2002: feminine, pure, transparent and bewitching. The 2001 Bonnes-Mares is shown at Sarah Marsh’s 2000/2001 horizontal in London. It is smooth and sensual, fresh and energetic if just exhibiting a slight bitter edge on the finish, whilst the 2000 Bonnes-Mares could be criticized for revealing too much of the stem addition, although I admire the marine-tinged finish.

Moving back to the 1990s, we commence with the brilliant 1999 Bonnes-Mares that is tasted three times in Paris, London and Hong Kong. All three showings evince a concentrated, exuberant and powerful wine with hints of kirsch, perhaps the most precocious of Roumier’s recent vintages. That is partly because he de-stemmed 80% of the crop and that remaining 20% is crucial in counterbalancing the intrinsic richness of this wine. Bottles should remain in the cellar long after you have broached the 2000 and 2001, possibly even the 2002. It might be the most Amoureuses-like of Roumier’s vintages and I must confess, I am a sucker for it, even though the 2002 is more my personal style. The 1998 Bonnes-Mares is poured at both verticals. The vintage might lack the acclaim of the 1999, but do not dismiss this 20-years-old because it is a huge success for Roumier, much more intense and opulent than expected with hints of eucalyptus cropping up here and there. Wonderful! The 1997 Bonnes-Mares, 50% de-stemmed, is earthier yet well delineated, although I find this bereft of the complexity expected from either a Grand Cru or a wine with Roumier’s name upon it.

“If you tasted the 1996 Bonnes-Mares in barrel, it was like the 2005 which soon shut down after bottling,” Christophe Roumier explains as he pours the wine. “I trust it. But it is not my favourite at the moment.” I concur. I cannot get my head around this rather introspective Grand Cru. In a nutshell it lacks that simple ingredient – charm. The highpoint of that decade is undoubtedly the 1995 Bonnes-Mares, a vintage I have been lucky enough to drink three times in the last 12 months. “Christophe just did not put a foot wrong in 1995,” a maven opined recently and he is completely right. This is just “singing” at the moment with a bewitching bouquet, a balance that warrants the word “symmetry” and a precision on the finish that is spellbinding. It is à point, but it will age gracefully over the next two or three decades. I find the 1994 Bonnes-Mares rather green; I am unsure whether it achieved full ripeness in that difficult growing season. Much better is the 1993 Bonnes-Mares, a growing season maligned on release but wow, how those reds have blossomed in recent years. This is a gorgeous wine with hints of Lapsang Souchong on the nose, quite burly and powerful on the palate with a captivating sapid finish. The 1992 Bonnes-Mares, which I encountered twice recently, is disappointing on the lean and herbaceous nose, redeemed by a commendable palate albeit with a stalky finish. Roumier explains that the 1991 Bonnes-Mares was affected by hail on 22 August and consequently it was cropped at just 15hl/ha. Yet it shows extremely well, like many 1991s, with impressive vigor on the bergamot tinged nose and a wonderfully balanced, quite substantial finish that comes as a surprise. The 1990 Bonnes-Mares, tasted both in London and Hong Kong, is a marvelous wine. I know that some dislike the vintage since it can translate more the warmth of the growing season than the terroir. But Roumier really managed to produce a voluminous and decadent wine that retains the essence of terroir and mineral tension. It combines hedonism and intellect to brilliant effect.

Moving back into the 1980s, the 1989 Bonnes-Mares is rather malnourished on the nose, afflicted by the same greenness that mars the 1994; I dislike the menthol character on the finish. As I already discussed in my introduction, the 1988 was unique in terms of two cuvées being bottled, the regular and the Vieilles Vignes. I was fortunate to compare them side-by-side and blind both in Hong Kong and London. I had only tasted the Vieilles Vignes several years earlier. Of course, on paper the 1988 Bonnes-Mares Vieilles Vignes should be better, right? Older vines equal better wine. Nothing complicated about that...except in Hong Kong when the identities were revealed, I preferred the regular 1988 Bonnes-Mares. Now, that was not in the script. I just find it more elegant and refined, heavenly on the nose and almost Musigny-like on the palate that shimmers with tension. The Vieilles Vignes is more opulent and slightly floral on the nose with wondrous salinity on the finish and yet, I still prefer the regular cuvée. Fast-forward to London and I tell Christophe Roumier the story. He looks at me with a little incredulity, quietly convinced that the Vieilles Vignes will triumph. Except that when the bottles are unveiled, yet again, I prefer the regular cuvée, likewise many of my fellow attendees.

The two 1988 Bonnes-Mares, regular and Vieilles Vignes, here pictured from the London tasting

But hold on a moment. One thing I learned from these tastings is that their differences are not simply a result of vine age. Have a quick read of my introduction again and there are differences in picking date by a considerable ten days, whilst the Vieilles Vignes contains 50% stems but none in the regular cuvée. This makes me think that Roumier did not intend for them to be compared ceteris paribus, but rather meant for each to be the best they possibly could, thereby persuading him to pick on different dates and vinifying with or without stems. Whatever he felt best. It transpires that the right decision was to pick earlier and use less stems. Thirty years later, the regular cuvée seems to be better, though both are stupendous.

The 1986 Bonnes-Mares is quite forward in style but I appreciate the crushed stone element on the nose and, in what was a tricky Burgundy growing season, it has commendable fruit intensity and a lovely sappiness. As I write in my note, it wears its heart on its sleeve. Now we come to the 1985 Bonnes-Mares and just in case you are not envious already, this is served out of magnum in Hong Kong and in bottle in London. It was the magnum that just left me lost for words. Perfection. Have a read of my “Bordeaux in Excelsis” article to remind yourselves of the criteria I look for on the rare occasion I am moved to give a perfect score. That is an apt word... I am “moved” by the magnum in terms of its ineffably complex bouquet, its purity, its finally sculpted tannin and length. Pinot Noir does not get any better. The 1983 Bonnes-Mares is far more mature than the 1985 and although it deserves applause for avoiding any scents of rot that besmirches many 1983 red Burgundies, I found the finish dry and a little mealy. The 1982 Bonnes-Mares is Roumier’s maiden vintage upon joining his father. I wondered to what extent it was chaptalized because it is difficult to discern the terroir here and feels a little ersatz and sweet on the finish.

Now we enter the era known as “B.C.”

Before Christophe.

Sadly, the 1980 Bonnes-Mares is compromised. It is not corked but it smells very yeasty, a shame because many 1980s are drinking beautifully. Moving into the 1970s, we enter a territory that I have no experience of and no means of comparison. The 1978 Bonnes-Mares is rejected as being corked. “Keep your glass,” I advised Roumier. “I think it’s just a bit of funk and might blow off.” Sure enough, that is exactly what happened and after a couple of hours it is showing very well, albeit in a much more rustic style compared to the 1985. And what an opportunity to actually compare them side-by-side. As expected the 1977 Bonnes-Mares is poor but strangely not undrinkable despite what must have been much chaptalization, whilst sadly the 1976 Bonnes-Mares is both oxidized and afflicted with TCA.

Maybe hereon in that bottles would not be representative and perhaps we should prepare for disappointments? That was not to be the case.

The 1971 Bonnes-Mares shows beautifully. Rustic, earthy and gamey on the nose, quite rich and forward in style, the fruit ebbing away with aeration but certainly robust. It is not the greatest 1971 Burgundy I have ever tasted by a long way but evinces a wine that might have been impressive in its day. The 1970 Bonnes-Mares comes from a more difficult growing season than the 1971 but it has held up well with remnants of red fruit on the nose. Roumier mentions that this was over-cropped, hence some dilution on the finish. There is certainly no dilution on the regal 1969 Bonnes-Mares, a wine that I have actually tasted once before. It is a stunning wine, testament to its provenance as this came from Don Stott’s cellar. Floral and captivating on the nose with a touch of humidor, the palate displays exquisite balance and precision, cut from a similar fine cloth as the 1985.

Now the 1959 Bonnes-Mares needs explanation. This is probably the only time you will ever see this wine, which came in the twilight of Georges Roumier’s career. This particular bottle is labeled “Ancien Domaine Belorgey”, indicating that it comes from the parcel within terres rouges that was sold to Roumier and Domaine Clair Dau in 1952. Christophe Roumier’s father kept it separate from his parcels in terre blanches until 1962, whereupon he blended them together. So, this is a fascinating insight into the wine and it delivers on the nose with a sublime bouquet of red fruit tinged with Turkish delight. The palate articulates the precocious growing season of that year, quite full-bodied and savory with hints of dried blood towards the finish.

That is the end. That represents all the bottles that Jordi assembled over the years. Time to go home...

“I brought a couple extra bottles with me, from my grandfather’s reserve,” said Roumier. “I will serve them blind and see if you can guess the vintage.”

Now, given the circumstances and what we have already tasted, you can imagine the anticipation in the room. What could he have brought?

My God. They are both astonishing, otherworldly, profound and delicious. I made my guess, 1955 and 1949.

I was correct on the 1955 Bonnes-Mares. It ranks in the top five red Burgundy wines that I have ever encountered. It is utter perfection. The aromatics are pixelated, HD in quality with spellbinding mineralité. The palate conveys a subtle marine influence and the silkiness of a Romanée-Saint-Vivant. I will probably never drink it again, certainly not from the Roumier family’s own reserve and I have no doubt I will pay for my fortune in the afterlife. I can deal with that.

No, the second is four years older – the 1945 Bonnes-Mares. It is a pinprick to the heart. A vintage loaded with meaning and historical significance guaranteed that it would be profound and thought provoking. I ponder the two bottles, the 1955 and 1945, tempted to give them both perfect scores but then the 1955 glistened a little brighter. Stupid, isn’t it? Awarding scores to rara avis like these but hey, at least when somebody asks which Burgundy have moved me to use the word “perfection”, then here it is for the record.

Final Thoughts

Here is the question. If I were younger and wanted to celebrate the birth of my first daughter, then would I still be prepared to open that valuable 1985 Bonnes-Mares at a time when we had barely two pennies to rub together? Is it not selfish to drink in monetary terms, her first year at university or first car? I’ve reflected a lot about that whilst writing this piece. It perfectly illustrates how perceptions towards Burgundy have changed and how money skews pleasure derived from the beverage we love (a topic recently discussed by Andrew Jefford in his monthly column). I suspect the guilt would dissuade me from fetching the corkscrew and plunging it in. Then again, I think of Christophe Roumier martyring last remaining bottles of 1945 and 1955, not so much a monetary sacrifice but a sentimental one. I guess that’s the fascination with wine. We derive enjoyment from its ineluctable destruction. Our enjoyment obliges its eventual extinction. How many bottles of the 1945 or 1955 remain? You know, I didn’t want to ask.

Without doubt the two verticals, in particular the one held in London, rank amongst the most memorable in my 20 years as a wine professional. Savoring perhaps slightly startled by the 1945 and 1955 that concluded the vertical, you could feel the sense of elation amongst the attendees. Some flew in across the Atlantic just for the occasion. Everyone must have had sky-high expectations, tinged with a little hesitancy given the age of some of the bottles. We were lucky because in both tastings an immense effort has been put into provenance and also, the 1980 excepting, we were lucky in terms of TCA and oxidation issues. The biggest smile in the room? That might have belonged to Christophe Roumier. “I have never seen a tasting like this,” he remarked. “It is almost impossible that it will ever happen again.”

That is true.

Whether it is celebrating your firstborn or attending a memorable tasting like this, you have to cherish the priceless moment when they do happen.

(Thanks to my friends in Hong Kong who organized the epic dinner at the Mandarin Oriental Grill, to Jordi Oriols-Gil for the epic, once-in-a-lifetime vertical in London, and to Christophe Roumier for his insights during the tasting.)

See all the Wines from Youngest to Oldest

You Might Also Enjoy

Plundering Burgundy Past, Neal Martin, July 2018

Mugneret-Gibourg: Ruchottes-Chambertin 1945 – 2014, Neal Martin, June 2018

Life Is Funny Like That: 1999 & 2015 DRC, Neal Martin, April 2018

The Magic of d’Auvenay: 1989 – 2011, Neal Martin, March 2018

The Glorious 1999 Red Burgundies, Stephen Tanzer, March 2018

Domaine Leroy: The 2015s From Bottle, Antonio Galloni, March 2018