Browse using the new Vinous website now. Launch →

Printed by, and for the sole use of . All rights reserved © 2015 Vinous Media

Juxtapose With You: Pétrus, Lafleur & Le Pin

BY NEAL MARTIN | FEBRUARY 23, 2018

During the countless days researching my Pomerol tome there were inevitably periods between visits when I had to face the fact there is absolutely nothing to do there. Not even a café to buy a half-decent reviving espresso to keep me awake. As a consequence, I would sit in my rented car observing the wide expanse of etiolated nothingness of mid-winter Pomerol and mentally assemble what the ultimate Pomerol tasting might look like. I imagined dining at El Bulli, re-opened just for one night, the sommelier pouring ex-cellar magnums of postwar vintages such as 1945, 1947 and 1949. And at this phantasmal dinner, invitations to all male attendees had mysteriously been lost in the post so that only two invitees turn up, namely Salma Hayek and Margot Robbie.

Then I thought, hold on old chap. There is a higher probability of Salma and Margot turning up at this dinner than those bottles. Let’s be realistic. Upon further contemplation this Pomerol ne plus ultra shindig was obvious: a comparison of the Pétrus, Lafleur and Le Pin triumvirate as seen through the prism of the most revered vintages. Following the publication of my book, a friend Omar Khan, who founded the International Business & Wine Society, happened to ask what my dream tasting might be. So, I confessed (missing out Salma and Margot – I presumed Omar would take that as a given.) “Leave it to me,” he replied, and I forgot all about it. Two years later he called to advise that he had finally assembled all the bottles and could I propose a suitable date. He apologized for taking so long, the culprit, the 1982 Le Pin. You cannot simply phone up Jacques Thienpont and ask him if he could spare a coupe of bottles because he does not have any himself. Finally, one was found, albeit at considerable expense. I just prayed that it would not be corked.

The private dinner was held over a weekend with just a handful of attendees. Pétrus, Lafleur and Le Pin all served side by side, vintage by vintage commencing with the 2005, followed by 1998, 1995, 1990, 1989, 1982 and 1975, the last excluding Le Pin since it only debuted in 1979. I would be able to observe the wines over the course of three or four hours, crucial for bottles such as these. Like many, I remembered Robert Parker’s remark in his Wine Buyers’ Guide that only millionaires would be drinking the 1989 and 1990 Pétrus side-by-side. I was a long way off becoming a millionaire. But for this night I would feel like the richest man in the world.

Juxtapose With You

I want to stress something before continuing. The motivation of this dinner was not to divine who might be best. It was no beauty pageant. Yes, I know that you could average out my scores, numerically deduce which I prefer. That was not its raison d’être. Rather the idea was to see if we could ascertain the style of each wine, their differences and similarities, their respective evolution in bottle in terms of secondary aromas and flavors, in order for me to use this insight in my next edition of the book.

Before examining the vintages, we should remind ourselves of the basics. Firstly, we should examine their histories. The genesis of both Lafleur and Pétrus dates back to the late 19th century when Pomerol was simply an unknown backwater of Bordeaux. The seeds of Lafleur were sown in 1872 when Henri Greloud bought a small parcel of vines while it was the Arnaud family that assembled Pétrus. (My one failure in the first edition of the Pomerol book was to discover the amalgamation of these parcels after the publishing, but the second edition will include this information as a friend has filled in this crucial missing piece of the jigsaw.) Le Pin is a comparative arriviste, debuting with the 1979 vintage after widower Mme. Loubie sold her single hectare of vines to Gérard Thienpont in March that year, whereupon Gérard handed it to his nephew Jacques to run.

In terms of size, Pétrus is the largest at 11.5-hectares, followed by Lafleur’s 4.5-hectares and Le Pin at just 2.7-hectares, the latter a piecemeal expansion since only 0.6-hectares were in production in its first three years. Geographically, Petrus and Lafleur lie in close proximity, contiguously in the southeast corner of the vineyard, whereas Le Pin is located further south, just outside the village of Catusseau. However, soil matters more than map co-ordinates. Even though Pétrus and Lafleur are virtual neighbors, the terroir differs. Pétrus lies on the so-called “buttonhole” of blue clay called smectite. You will have to refer to my book for a molecular explanation of the advantage it gives to vines, but essentially smectite is supremely gifted at water absorption and retention. Lafleur does not possess any vines on blue clay, but sits on the gravel plateau. However, it is not homogenous, the land a veritable “mosaic of geological profiles” consisting of gravel, clay, silt and sand.

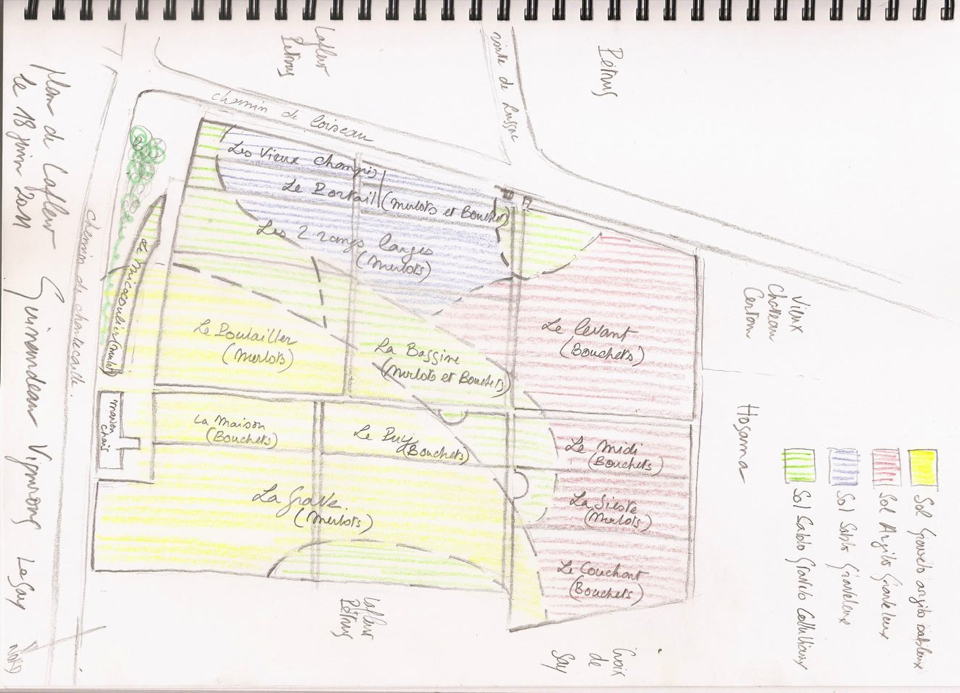

A little gift for Vinous readers. This is the original “cartographic masterpiece” sketched by Jacques Guinaudeau for my book. He painstakingly colored in the mosaic of soil profiles, only for the printed copy to be in black and white. So, for the first time, here is the original version replete with the ring bindings on the sketchbook that housed all the growers’ maps. Sadly, it went missing.

Perhaps the most significant difference are the grape varieties. Pétrus and Le Pin are pure Merlot. Old vintages of Pétrus intermittently included a sprinkling of Cabernet Franc, although it was never more than a couple of percent if any at all. Lafleur is divided equally between Merlot and Cabernet Franc. The final blend varies from year to year, but I always feel that it is the Cabernet Franc that defined Lafleur’s character. There is a historical connection between Pétrus and Lafleur that stems from the devastating spring frosts of 1956. The redoubtable Mme Loubat, proprietor at Pétrus, refused to pull up her vines like others. Instead she pruned surviving vines back down to a nub (known as recépage) and prayed that a shoot would sprout from the trunk the following season, thereby maintaining original vine stock. Marie and Thérèse Robin, the spinsters at Lafleur, were a bit naive in matters viticultural and could not countenance the prospect of pulling up and replanting the vineyard. So, they just copied Mme. Loubat.

Pétrus undergoes a short pre-fermentation maceration (although there are variations in accordance with the growing season that I will signal in my explanation of the vintages). Malolactic fermentation is done in concrete tank, a central tenet of Jean-Claude Berrouet who dislikes malo in barrel as it tends to detract from terroir expression and homogenize the wine from year to year. It is matured in around 50% new oak from Demptos, Seguin Moreau and Taransaud. Le Pin is fermented in stainless steel tanks, occasionally with a little saignée, and then matured in new Seguin-Moreau barrels, though Jacques has also used Taransaud after the new winery was rebuilt in 2013. Jacques Guinaudeau told me that he would stop the post-ferment maceration “when its taste no long pleases me.” Because of the heterogeneous composition of the soils and dual grape varieties, there is much trialing of blends before the final one is chosen (a process now undertaken with Jean-Claude Berrouet.) Here they use around 50% new oak, the same as Pétrus, from the Darnajou cooperage, although in the 1980s they would have used around one-third new wood. There is no second wine made at either Le Pin or Pétrus, though the excellent Pensées de Lafleur comes from a finger of sandier soils that runs through part of the vineyard.

The Guinaudeau family pictured in 2012 for my Pomerol book: Jacques and his wife Sylvie, Baptiste and Julie.

Finally, we can also compare the winemakers themselves. Though actually owned by his brother, it is Christian Moueix who oversaw Pétrus in the period in which these wines were born, Jean-Claude Berrouet the genius behind each and every one and, as we will discover, not only Pétrus. Jacques Guinaudeau, the second cousin of Marie and Thérèse Robin, began making the wine at Lafleur from the 1985 vintage, eventually buying the property with his wife Sylvie in 2002, their son Baptiste and partner Julie taking the reins in recent years. Le Pin has always been Belgium-born Jacques Thienpont’s “baby” since its inaugural vintage, buying out his Gérard’s shares in 1987 so that Le Pin is a joint-ownership between him and Alexandre Thienpont at Vieux-Château-Certan.

The Wines

Though we approached the wines from youngest to oldest, I will narrate the wines the opposite way around to tell this interwoven story between the three growths.

We begin in 1975. Le Pin does not exist, so we just have the 1975 Lafleur and 1975 Pétrus to compare. The Robin sisters made the 1975 Lafleur under a very different regime than others included in this tasting. Whereas others abided by contemporary techniques of viticulture, the 1975 was “old school” winemaking little changed from the war. They were rather indifferent to winery hygiene as evocatively described by Parker who recalled poultry clucking around the barrels. (Incidentally, 1975 was the year that Parker first visited the château.) I have only encountered this vintage once in 2004 when it was very deeply colored and very tannic on the palate. This bottle had a fabulous, complex, rustic bouquet that stopped you in your tracks, the palate aptly described in my note as a “heavyweight bruiser”. It is not the subtlest of Lafleurs and yet you had no choice but to stand back and admire this “monument”. Whereas the 1975 Lafleur could be regarded as a fortuitous success, the 1975 Pétrus was more a result of Jean-Claude Berrouet’s accumulation of empirical knowledge, learning each vintage. The 1975 has always been his favorite of this era, the vintage where he felt everything came together in terms of praxis. The best bottle I have drunk was shared with Mrs. M. to celebrate her “Big four zero”. I remember it being so rich and seductive with sloes, black olive and leather, the palate underpinned by filigree tannin, satin-like texture and gorgeous black fruit. This bottle was the only one that was off-kilter at the tasting. It just did not sing aromatically with traces of leather and brown sugar, the palate finally revealing the luxuriant nature of previous bottles with hints of bay and curry leaf. (Fortunately, I have tasted the 1975 Pétrus since then and I will report on that separately.)

This is the famous photograph of Jacques Thienpont that adorns the Le Pin chapter in my book. It took several attempts for Johan Berglund to get this shot.

To compare side-by-side the 1982 vintage from Le Pin, Lafleur and Pétrus constitutes a pinch me moment. If you are wealthy and money is no object then you can find Lafleur and Pétrus on the secondary market. Try finding a bottle of 1982 Le Pin. Flapping a wad of cash in the air will do little good. It is like looking for a needle, or maybe that should be a “pin”, in a haystack since only around 1,800 bottles were ever made. It is this wine alone that delayed this tasting in order to find a bottle that was a) real b) of sound provenance c) not priced equivalent to the GDP of a small equatorial country. After all that, keep in mind folks that the 1982 Le Pin hit the market at a whopping ten pounds a bottle. Upon release, nobody really noticed or cared. In fact, I know a merchant in the UK who reckoned he was sitting on about half the production after its initial release and that sales were sluggish for many months.

The three 1982s side by side. I have noticed that old bottles of Le Pin often have this mottled staining on labels.

For the purpose of this article, I beg you to put the fact that these three bottles alone could fund your kids through college to one side because it is so fascinating to compare where each of these Pomerols were in 1982. Pétrus was revered as one of Bordeaux’s greatest wines with a track record stretching back to the 19th century Cocks & Feret guides. Lafleur had more of a cult following; far less known apart from being a rather rustic, rough hewn but intermittently magical wine that tended to take years to mature. Le Pin was just another Pomerol with miniscule production, a large proportion of vines only in their fourth leaf, made in the basement of a rather disheveled farmhouse by a funny Belgium chap. Thérèse and Marie Robin were old and frail and asked Christian Moueix and Jean-Claude Berrouet if they would mind making their Lafleur (and Le Gay) in 1982. Curiously, having tasted both several times over the years, there is no question that they produced a stellar wine at Lafleur whilst the Pétrus has its attributes but has never lived up to the billing and certainly not its market price tag. Juxtaposing these two bottles simply provided more evidence: Lafleur demonstrating greater density and complexity, a genuinely perfect wine because you cannot fathom how it could be any better. The 1982 Le Pin is a sui generis. It is cut from a completely different cloth to Pétrus and Lafleur. This was the third time I had tasted a bottle and it delivered as expected: an outrageous, exotic, lush, opulent wine with veins of blue fruit. It feels almost viscous in texture yet retains astonishing balance. Maybe Lafleur is the noble and profound wine but who can deny that the 1982 Le Pin is just a damn sight more fun, not to mention that it has aged remarkably well. Some might find it garish however, if the raison d’être of wine is to elicit sensory pleasure, then the 1982 Le Pin is a total success.

Since the two vintages are always compared together, let’s tackle the 1989 and 1990. Firstly, the triplets born in 1989 outclassed 1990. This reaffirms my view that whereas a decade ago they were neck-and-neck, the 1989 Pomerols appear to be ageing with more style. The 1989 Pétrus is sublime and profound, an example of fermented grape juice that truly merits a perfect score. It encapsulates everything you desire from this iconic estate and after almost thirty years it seems to continue improving year upon year, putting a gap between itself and the 1990. The 1989 Lafleur was perhaps the surprise of the entire tasting, though if I had recalled my half-a-dozen effusive previous notes, maybe I should have expected it. It is more dense and structured than the Pétrus, but here I was gob-smacked by its clarity and precision, perhaps a facet I have overlooked. It is worth remembering that when Jacques Guinaudeau made this wine he was not the de facto owner and with France’s convoluted inheritance laws, it was not guaranteed that he and Sylvie would be able to buy the property as and when Marie Robin passed away. The 1989 Le Pin is a wine that I have encountered three times, the last in Hong Kong when it was utterly gorgeous. Here it performed extremely well, borrowing some of the leftover luxuriance from the 1982, opulent and lavish yet with stunning balance.

As I mentioned already, the 1989s are a step ahead of the 1990s. Although the 1989 now offers more complexity and renders you speechless, the 1990 Pétrus is still a truly great wine and the best of the three. There is more volume, a little more swagger about this Pétrus but it just does not quite have the same breeding and je ne sais quoi as the 1989. Perhaps the 1990 Lafleur was the one showing that underwhelmed vis-à-vis previous encounters with this wine and against the 1989. Unlike the previous vintage, it seemed to translate more the warmth of that growing season instead of the terroir. It took 30 to 40 minutes to really start revving its engines but never quite clicked into fifth gear. The 1990 Le Pin has always been a seductive, harlot of a wine that you cannot help falling for. I remember drinking this from a magnum a decade ago and you could almost describe it as “orgiastic”. It is now fully mature, more feral and animally on the nose compared to either Lafleur or Pétrus, yet with great depth and roundness. As I wrote in my tasting notes, it reels you in with its “giddy plushness”. If I had bottles in my cellar I would be popping them open now because this wine will not improve further.

We move on to 1995, incidentally a flight that we opted to taste blind. Here I feel that Lafleur and Pétrus vie for first place. Certainly, the Lafleur might be held up as the best wine of the decade for Jacques Guinaudeau. I have probably tasted this a dozen times now and it always delivers the traits you expect: the structure, the density, that backbone, secondary notes of fennel and mint. With respect to this bottle I remarked upon a little more blue fruit in the mix and a slightly tertiary finish. You could broach bottles now after 20 years although personally I would give it a couple more in bottle. The 1995 Pétrus might be seen as its “comeback” after a fraught first half of the 1990s, where cool and rainy growing seasons prompted Christian Moueix to take extreme measures in the vineyard, famously using plastic sheeting to allow the rain to run off in 1992. The 1995 Pétrus is a magnificent return to form although I must confess that I mistook it for Lafleur because of its savory palate that I erroneously attributed to Cabernet Franc! But I love the density and length of this Pétrus and even if it does not offer the same brazen audacity of the spellbinding 1998, it should continue to drink well for a couple of decades. The 1995 Le Pin has always been a curious wine. I remember first tasting it blind around 2004 and being rather unimpressed, unlike the 1994 Le Pin that I have long considered a great success for Jacques. I remember asking Alexandre Thienpont why the 1995 did not perform well and he quipped that Jacques was busy woo-ing his wife-to-be! That said, this was actually the best example of the 1995 Le Pin that I have encountered, appreciating (blind) the mineralité and the purity of fruit, that subtle, marine influence surfacing towards the finish. Perhaps it is a Pomerol that just decided to take many years to come around?

Christian Moueix, pictured here at this home. Though he was not the actual owner of Pétrus, he was the man at the helm from the early 1970s until three or four years ago.

On to the 1998, a vintage renowned for its Right Bank wines. Let’s cut to the chase: the 1998 Pétrus is possibly the greatest Bordeaux of the decade (closely followed by the 1996 Château Margaux in case you are wondering). It is a Pétrus that rivets you to the spot: the control and precision of the aromatics, so intense but never overbearing, the manner in which it unwraps those floral scents. The palate has a sense of symmetry that staggers belief and a length that leaves you feeling bewildered. This is Jean-Claude Berrouet at the peak of his powers. To be honest, it shades both the Lafleur and the Le Pin. The 1998 Le Pin is a delicious, velvet-textured, decadent wine that if I am to quibble, just nods a little too eagerly towards Napa for my own liking. The 1998 Lafleur was broody and obdurate by comparison, to the point where it seemed to quash hopes of actually enjoying it. Maybe it will soften at 25 or 30 years of age but at the moment it just forgets that oenophiles would like to enjoy their wine.

The most recent vintage on the table that night were the three 2005s. Unfortunately, the 2005 Pétrus was our one corked bottle, although I was fortunate to taste the same wine at a private dinner a few weeks later. This might be considered Jean-Claude Berrouet’s last great Pétrus before handing over the reins to his son Olivier. The word that describes this wine is “crystalline” although I observed that it remains quite backward and reserved, certainly in need of another four or five years in the cellar. The 2005 Lafleur, which was made by Jacques and his son Baptiste and partner Julie, is typically evolving at a glacial pace. My God, anyone opening this Pomerol before it reaches adulthood is making a mistake: such concentration and structure, a behemoth that only time will abrade and soften. I felt that the 2005 Le Pin is not quite in the same league as those two. It has an almost Burgundy-like purity on the nose although I felt that the winemaking just spoke a little too loudly on the palate. Hopefully that will ebb with time in bottle, but it does not possess the same structure and depth as either the 2005 Pétrus or Lafleur.

That bought us to the end of a remarkable evening. As I mentioned already, this was not a tasting to see what is best. You might argue that my sentiments towards Pétrus and Lafleur seem to contain more ardor than Le Pin, on the other hand, neither of those have ever created as wine as decadent and luxurious as the 1982. In terms of style, Le Pin is clearly the sweeter, lush, velvety and opulent. I tend to like Le Pin more in cooler vintages, especially in recent years, because it offers more mineralité courtesy of the gravel. If you have a penchant for wines that express purity of fruit then Le Pin might be your pick. Even though both are 100% Merlot, there are tangible differences between Le Pin and Pétrus and that must surely be down to the soil: blue clay at Pétrus, more gravel at Le Pin. I have always said that the smectite lends Pétrus that extra something. That is not to say that it will be superior by rote however, in some vintages it just goes that extra unimaginable step that turns 99 points into 100, such as in 1989 and 1998. Also, one cannot ignore that Pétrus has had two magicians at its helm: Christian Moueix and Jean-Claude Berrouet. The latter made every vintage from 1964 to 2007 – that kind of experience, familiarity with every square foot of the vineyard, is something that cannot be learned at school. Lafleur is the most introspective, challenging and occasionally enigmatic of the three. It often performs poorly in blind tastings and requires at least a decade, preferably two in bottle, before revealing its true personality. It can achieve a level of complexity that is difficult to translate into words, the fruit blacker than Pétrus and Le Pin, often earthier and a little grittier in texture. Yet the 1982, 1990, 1995 and 2005 demonstrate that Lafleur can flirt with perfection when the wind blows favorably.

I commence research on the second edition of Pomerol this year. It was always my intention to publish a second edition ten years after the first. This tasting was invaluable being able to assess first-hand the stylistic difference between the three wines. Hey, maybe one day that fantasy tasting of postwar magnums of Pomerol will come true.

Hey...hang on a minute...Salma on the phone...

(I am indebted to Omar Khan of the International Business & Wine Society (www.businessandwine.co) for organizing this incredible dinner at the Four Seasons Hotel in London. Map of Lafleur, the Guinaudeau family and Jacques Thienpont copyright The Wine-Journal Ltd/Johan Berglund.)

You Might Also Enjoy:

2008 Bordeaux: A Day In A Life, Neal Martin, February 2018

So Neal, What Can I Expect?, Neal Martin, February 2018

Pichon Longueville Comtesse de Lalande 1921-2016, Antonio Galloni, October 2017

Larcis Ducasse Retrospective: 1945-2014, Antonio Galloni, March 2017