Browse using the new Vinous website now. Launch →

Printed by, and for the sole use of . All rights reserved © 2015 Vinous Media

Burgundy 2024: One Battle After Another

BY NEAL MARTIN | JANUARY 8, 2026

Côte de Beaune: Beaune | Chassagne-Montrachet | Meursault | Pernand, Aloxe & Ladoix | Pommard | Puligny-Montrachet | St. Aubin, Monthélie & Maranges | Volnay

Côte de Nuits: Chambolle-Musigny | Fixin & Marsannay | Gevrey-Chambertin | Morey-Saint-Denis | Nuits-Saint-Georges | Vosne-Romanée

The Deity Wine Circle is on its annual trip to Burgundy. This year’s merry band includes God, Zeus, Vishnu and Demeter, plus Rudolf Steiner and a dog, the gods of biodynamics and dyslexia, respectively. Mother Nature occupies the front seat, absorbed in her Instagram account, clips of her suggestively uncorking Burgundy accompanied by sultry remarks…

“You’re such a Grand Cru…”

“You saucy Amoureuses…”

Jesus is behind the wheel, His messianic vision impaired by torrential rainfall. Wishing to remain incognito, the group hired a black Mercedes people-carrier, aiming to blend in with dozens of others forming funeral corteges behind tractors tootling along at walking pace. However, the deities cannot help drawing attention from passers-by, what with their glowing robes, lightning bolts from fingertips, blue skin, etc.

“Can’t you do something?” whines Jesus. “I can hardly see, even with my halo on full beam.”

“Winemakers ‘ave been moanin’ ‘bout ‘eatwaves ‘n droughts, vines wiltin’ in the sun for bloomin’ ages,” counters Mother Nature.

“These downpours would have been edited out of the Old Testament for being far-fetched. Dad, can’t you do something about it?”

“Sorry,” God replies. “Mother Nature is in charge of the weather. She does seem to have lost control in recent years.”

“We’re here,” announces Jesus, pulling the handbrake. “Looks like a long queue.”

Indeed, stationary black vans snake from the cross of Romanée-Conti to the Porsche showroom in Vosne-Romanée that caters to local demand, offering designer detachable ploughs and even Stella McCartney atomisers. An hour later, the group is posing in their matching sou’westers in front of the cross. Jesus declines. Crosses conjure bad memories.

Next stop is a new producer, Domaine Next-Big-Thing, since that is the word on everyone’s lips. They punch it into the satnav, which directs them to a derelict piece of land between Domaine Under-the-Radar and Maison The-New-Coche. A portly man in a tailored pinstripe suit shelters under an umbrella and springs from a rickety wooden chair.

“Bonjour,” he cries, arms outstretched like a preacher. “Welcome to Domaine Next-Big-Thing.”

“Excuse me, but there’s nothing here but puddles,” God remarks incredulously. “The only person who can make wine from water is my Son.”

Jesus takes his flask of mineral water, points his finger, and it instantly turns into Romanée-Conti 1947. His phone rings. Some guy called Rudy.

“No vines yet,” the man answers. “But our tech-bro investors used AI to identify a boy-genius born to revolutionise Burgundy.”

He hands God a Polaroid of a bespectacled lad grinning at the camera. He looks like Harry Potter brandishing a pipette instead of a wand.

“He appears about ten years old.”

“Correct. His mother mixed Montrachet with his formula milk, read him passages of Enjalbert and Chauvet at bedtime, and by kindergarten he was reciting biodynamic preparations to his imaginary friend, Guyot.”

“I’m in,” interjects Rudolf Steiner, his root day brightened.

“We just need to buy the vineyard and err…build a winery,” he continues. “Then, charge prices that insult the laws of economics.”

At that moment, a party of influencers turns up and begins rating his non-existent wines based on vibes and coolness. The gods cannot wait a decade for Domaine Next-Big-Thing’s debut and depart.

The rain continues relentlessly. Vineyards make quagmires look like manicured lawns. Labourers toil through rows and spray during dry interludes, the sound of raindrops interrupted by wails of woe not dissimilar to those heard after the last Bordeaux primeur campaign.

“You are all-powerful,” says the dog. “Just click your fingers. You could make all this go away.”

God turns to dog.

“You are right. And sometimes I do answer prayers. However, winemaking is a gamble with nature. Some seasons are a walk in the park, others a minefield. Sometimes a vintage will take you to the brink with little clue about the end result. It can be worthwhile, even if you don’t feel that at your lowest ebb.”

And with that, the people carrier ascends into the dark clouds above in a flash of light that momentarily gets winemakers’ hopes up, before once again the land is shrouded in inclement gloom.

The Growing Season

The headline in 2024 was the four-letter word beginning with the letter “r,” and no, it’s not “ripe.”

Rain.

There was more rain in 2024 than in 2022 and 2023 combined. There is some nuance to that arresting headline. You must examine what transpired at ground level. Whilst no winemaker was completely spared, there were variations in precipitation. This predicated exponential divergences in terms of consequence and how winemakers addressed them. In fact, 2024 was one of the most storied and complex growing seasons that I have covered in over two decades.

Frost: The Forgotten Blight

Two thousand twenty-four was not frost-free. It put paid to Thibault Liger-Bélair’s Clos de Vougeot, and the winemaker asserted that he lost more to frost than mildew or flowering. Vincent Dureuil-Janthial also cited frost as a significant factor, primarily because Rully tends to be cooler than other appellations. There was no dramatic Arctic freeze like in 2016. Instead, there were three frost episodes around Santenay, Saint-Aubin and the Hautes-Côtes between April 18 and 23 when temperatures hovered around freezing. Already weakened vines resisted for the first three days and finally succumbed, yet it was only in hindsight that vineyard managers realised the damage. Marsannay was the exception, as temperatures there plunged to -5°C and damaged 80% of the most exposed parcels. In addition, this cold spell decreased the number of inflorescences, which would come to exacerbate low yields at flowering.

Anyway, by that time, growers had plenty of other things giving them sleepless nights.

Rain and Mildew

As I have written before, a growing season does not start the moment calendars flip on January 1. Apropos 2024, the purview goes back to when the 2023 harvest finished. October to December 2023 saw 88 millimetres (mm), 97 mm and 84 mm of rain, respectively. Though January and February were slightly drier, March witnessed 111 mm over 16 days of precipitation. Therefore, even before the growing season began, the land was already soggy, rendering it more difficult to undertake winter tasks. The only glimmer of hope was that budding took place in a rare spell of warm weather on March 30 and 31.

Henceforth, there was never a dry spell. Clouds were constantly plotting the next shower. Temperatures between April and July languished below normal. Mildew usually attacks in late spring when temperatures rise in humid conditions; however, in 2024, some winemakers reported that mildew pressure was building as early as vines’ third leaf. The Vitiflash report cited heavy rain on April 9 as a trigger, and more pessimistic vignerons were writing off any harvest before flowering. It felt permanently cool, overcast and rainy. Jeremy Seysses at Domaine Dujac reported 65 rain events that could potentially increase mildew. Though April saw average rain, May was soaked with 97 mm and June, 88 mm.

What I should press home is that it was not the extremely high level of precipitation that caused such damage. Instead of biblical downpours, it was the regularity of the showers, almost “every other day,” to quote some winemakers, so that they felt as if they were never off the hook. Even morning dew exacerbated the mildew. Vines were sapped of energy fighting these conditions, deprived of sunlight that might have revitalised them. It was prolonged meteorological torture.

The inclement conditions, oscillating temperatures and showers severely disrupted flowering, which was strung out over many days. There was a poor fertilisation of inflorescences (clusters of flowers on the stem) concurrent with a deterioration of sanitary conditions on the flatter parts of the Côte d’Or, where regional whites and reds are located. Parcels on the slope were less impacted. Clément Barthod at Ghislaine-Barthod, who tends farms in both the Côte de Nuits and Côte de Beaune, told me that flowering was better in the latter. “We had a beautiful week down there, whereas it started raining in the Côte de Nuits,” he explained. Coulure was widespread. Many winemakers echoed that this decimated yields more than mildew. Without wishing to sound facetious, in some areas mildew was no problem because there were no bunches for spores to infect. Conversely, those who did breathe a sigh of relief after being spared poor flowering had more to lose.

Before continuing, pause to consider the impact on the teams. Permanently dressed in waterproofs, battling to save what they could, they contended with glutinous, slippery, clayey earth underfoot that often made it impossible or even dangerous to drive tractors through the vines. Many had to be sprayed manually with heavy backpacks—slow and laborious. I even heard of a couple trialling the use of aerial drones. Is this technology that will become prevalent in the future? There were few dry windows to apply protection, and when those windows coincided with weekends, it raised the question of whether you could get the workers on that day—not easy with the 35-hour rule. If there was a window to spray, it would be washed off by the next shower within a few hours. It takes just 15-20 mm of rain to wash away sprays and render all that work null. That is exactly what transpired every other day.

In effect, many growers were playing catch-up with the spread of mildew infection. Mildew is a cryptogam, spread by spores that thrive in warm humidity. With a four-day cycle, mildew cannot be cured once it takes hold. Protective sprays are only effective if applied preemptively. Afterwards, you are just mitigating losses against the mildew’s exponential spread. Antoine Gouges put mildew spread into perspective, explaining, “If the vines grow quickly, then the mildew cannot keep up with the growth. But when the vine virtually stops [as it did in 2024], the disease progresses faster and infects more of the surface.”

The Divergence

At this point in the season came the divergence between Chardonnay, which populates much of the Côte de Beaune, and Pinot Noir in the Côte de Nuits. The earlier-ripening Chardonnay enjoyed not an even flowering per se, but certainly one less disrupted. Secondly, Chardonnay is more resistant to mildew than thin-skinned Pinot Noir, and even here, there were further divergences between field selections such as Pinot Fin and Pinot Droit, the latter reputed to be more resistant to botrytis pressure since the former has clusters that are less compact.

A storm in early June exposed these variations, exaggerating differentials between infection spread from one vineyard to another. This storm came at the most inopportune moment during flowering, but it struck the Côte de Nuits rather than the Côte de Beaune. Aside from the storm’s immediate impact, it also accelerated the explosion of mildew in subsequent weeks—the snowball effect—widening the gap north and south of Beaune ville. The most acute attack of mildew was between Beaune and Gevrey-Chambertin, with Marsannay suffering less. It is one of the major factors that split the growing season in two.

Why is the Côte de Nuits seemingly more beleaguered by precipitation than the Côte de Beaune?

There seems to be a trend in recent years. Whilst there is no conclusive proof, many cite the combes—the small valleys that cut into the Hautes-Côtes perpendicular to the north-south orientation of the Côte d’Or—as a landscape feature that foments cloud formation and rainfall. There is the Combe de Lavaux in Gevrey-Chambertin and Combe d’Orveau facing Clos Vougeot. Surely, it cannot be a coincidence that appellations exposed to these valley formations took the brunt of the rain?

Cover Crops

One important factor in 2024 is the use of cover crops. The planting of cereals or legumes between rows of vines has traditionally aimed to increase competition in the vineyard, to tweak the vines’ stress. However, several advantages and disadvantages came into play in this vintage more than any other.

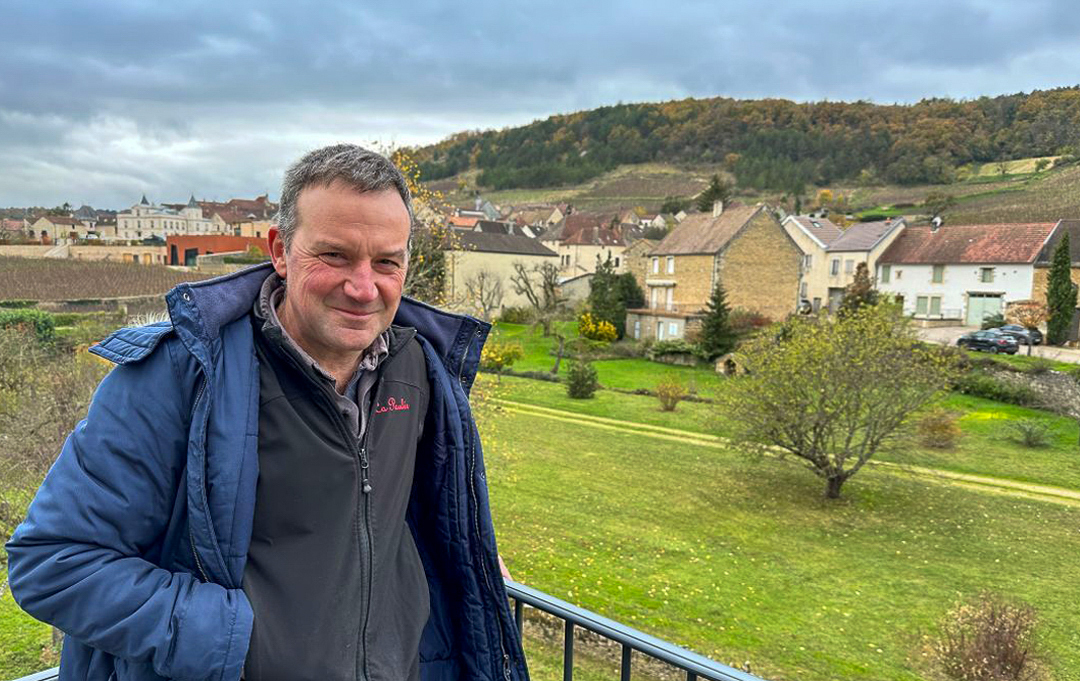

Posing on the rooftop terrace over the roofs of Vosne-Romanée, Mathilde Grivot used cover crops to help workers manoeuver around the vineyard.

Firstly, cultivating tall grasses and then flattening them—what is termed “couché l’herbe,” literally “sleeping”—gave vineyard workers more traction underfoot. This was crucial for enabling tractors to enter vines to spray ahead of mildew attacks, as well as making it easier for workers themselves. Mathilde Grivot used cover crops specifically for this purpose. According to Sébastien Mazzini, cover crops’ roots also enhance drainage. They can absorb some of the moisture in the earth while also preventing splashback onto the vines that can occur with bare ploughed soil. Additionally, cover crops can be mulched into the soil to increase nitrogen content.

However, growers had to be very careful in 2024 because these crops adversely increase humidity, which is precisely what you do not want in periods of extremely high mildew pressure. One of the defining factors that determined the success of wines in 2024 is how efficiently these cover crops could be controlled. With the constant rain, they grew quicker than normal, requiring constant cutting back so that they would not act as incubators for mildew or oïdium.

Rain, Rain, Everywhere?

Two thousand twenty-four is a vintage that exposes the most propitious terroirs. Sometimes there was a stark contrast between two adjoining vineyards, foregrounding the aforementioned difference from one red to another.

Let me present one astonishing statistic that epitomises the yawning disparities between locations. As explained, the constant deluge of rain is the headline, the defining factor that underwrites the shocking inequity of the vintage. Zoom in on the appellation of Chambolle-Musigny. The southern sector around Musigny/Clos Vougeot drowned in 50 mm of rainfall in a single day at the beginning of June. It would take you just ten minutes to walk from there to Bonnes-Mares in the north of the appellation. How much rain fell in Bonnes-Mares on the same day? Two millimetres. Such is twenty-four’s mordant wit.

Winemaker Jean Lupatelli has overseen a tangible improvement in the wines at De Vogüé.

I had just tasted the Bonnes-Mares and Musigny at Domaine Comte Georges de Vogüé when Winemaker Jean Lupatelli shared those figures, which really rammed home the polarities of the growing season. As a consequence, even within the portfolios of auspicious names in Chambolle-Musigny like Roumier or J-F Mugnier, there is unprecedented variation between cuvées. There are other examples of pockets with wide discrepancies. I mean, how did Sébastien Cathiard crop his Vosne-Romanée Malconsorts at 45 hectoliters per hectare when carnage lay around?

Organics Under Pressure

In 2024, some organic/biodynamic winemakers feared losing their entire crop and faced a conundrum:

Should they stick with non-synthetic sprays and risk wiping out the bunches struggling to fend off mildew day by day? Or, pushed to the brink, should they abandon organic principles and apply chemical treatments to salvage what remained?

These winemakers were caught between a rock and a hard place.

For Cyprien Arlaud, there was never any question about forsaking biodynamics, even in a season like 2024.

Those who are certified and have undergone the three-year transition process had all that to lose. Certified producers for whom organics or biodynamics are deeply ingrained—like Cyprien Arlaud, Pierre Trapet or Guillaume d’Angerville—told me that quitting was never an option. Those who practice organic/biodynamic viticulture without certification would lose nothing but self-imposed principles. This was a key factor in making that momentous decision. Consider the gulf between those blessed with deep pockets and no financial worries—not least those owned by luxury houses or wealthy outside investors—and those who are entirely dependent on income from their incipient vintage. Livelihoods were in jeopardy. Think of the countless producers, like Virgile Lignier or Arnaud Mortet, whose portfolios comprise a large percentage of fermage or rental contracts. Annual rents still have to be paid, however small the yield. Therefore, 2024 risked immense financial black holes.

Some domaines, such as Ghislaine Barthod, Jean Tardy, Bruno Clair, Laurent Fournier and Arnaud Mortet, could not countenance that risk and reluctantly applied chemical treatments. Mortet was particularly emphatic when he told me how he sensed trouble at the beginning of the growth cycle and unhesitatingly applied chemical protection. A common belief among winemakers is that waiting to take that decision until June, at the critical moment of flowering, was already too late.

Pierrick Bouley in Volnay stuck fast with his organic principles.

Opinions differed as to whether to abandon organic/biodynamics or not. Some winemakers averred that the inclemency was so extreme that how you treated your vines (biodynamic, organic, or synthetic) was moot. Ergo, what was the point in quitting? Pierrick Bouley in Volnay suggested that maintaining organic compliance only cost him 5-10% of his volume—a price worth paying. Mortet told me that he was only able to crop at 17 hl/ha because he applied chemical treatments early. Pierre Trapet, who farms biodynamically, got by with yields that languished between 5 hl/ha and 10hl/ha.

I sympathise with those forced into making that decision, particularly those who hold these principles close to their heart. It is unjustified to cast aspersions towards those winemakers who relinquished organics in 2024. A healthy working environment for vineyard workers is a goal to pursue, but viticulture has no bearing on my assessment of anyone’s wines. Indeed, most of those who applied chemical sprays did so frugally and, it must be stressed, immediately reverted back to organic or biodynamics in 2025, albeit without recertification. If 2024 taught winemakers one lesson, it was to keep their options open.

Before leaving this subject, there is the c-word…Copper.

As much as organic/biodynamic winemakers proselytise eschewing chemical treatments, the fact is that they must resort to spraying copper to protect their vines. Copper is non-soluble. Residues do not break down. They stay in the soil. There are concerns about its heavy use, even among the most ardent Steiner acolytes, so much so that restrictions limit copper use to seven kilos per hectare per year. French agency ANSES recently announced that 20 commonly used copper sprays will be outlawed beginning next year, and a new limit will come into effect, reducing use to an average of four kilos per hectare per annum. Any repeat of the 2024 growing season under these incoming limitations will force more winemakers to quit organic certification. Many find the proposal untenable and opine that it is actually likely to increase non-organic practices.

Lucie Germain at Domaine Henri Germain in Meursault, certified organic in 2024. There was no way that they would have applied chemical treatment.

Twenty-four was a psychological test. How long do you keep spraying for diminishing returns? Several winemakers mentioned the importance of holding out to the end. Jean-Marc Vincent in Santenay pointed out that if you can get to véraison, leaves become less sensitive to mildew infection as they contain less of the nitrogen that is then diverted into changing grapes’ colour. Vincent told me, “When the leaves feel like cardboard, you don’t have to spray anymore.”

This is a subject that deserves a standalone article. After 2024, there is growing acceptance amongst winemakers that instead of a black and white, organic or chemical decision, the goal should be to find an equilibrium that will balance the non-use of chemicals with maintaining a living—in other words, what is already termed “lutte raisonée.” Eschewing chemical treatments is a noble aim. However, when you are going in and out of your vineyard over 20 times in a year, considering all the petrol that uses, never mind the issue of soil compaction, an increasing number of producers are quite rightly thinking in less Manichean terms. That is why one should not evaluate wine based on agronomy.

Such was the fallout from all the rain that it is easy to overlook that there was some hail damage on May 20 that affected Marsannay (especially around La Grasses-Tête and Clos du Roy), as well as on August 1 that affected sectors in Chassagne (especially Les Vergers) and Puligny-Montrachet, Saint-Aubin (especially Charmois) and Pernand-Vergelesses (DRC lost 10% of their crop).

This photo was taken just before harvest as I drove back from a winery visit…and this was early September, supposedly when the Côte d’Or enjoyed its best weather!

The Saviour

The growing season thus far reads like scripture from the Old Testament, an annus horribilis like no other, according to some old hands.

What saved it?

Unquestionably, the sunny, warm August leading up to harvest galloped to the rescue. June and July saw 205 and 258 insolation hours (below average), but August saw 314. June and July experienced 112 mm and 75 mm of rain, while August received 24 mm. Average temperatures of 18.0°C and 20.4°C in June and July led to an August average of 21.0°C. The sun’s energy was channelled into surviving bunches hanging onto the vines, which by then could be 70% to 80% less than average. This clement weather nudged the berries towards phenolic ripeness and got fruit over the finish line. That would have been irrelevant had the weather deteriorated. Instead, it remained relatively benign and allowed winemakers to wait and pick, again, giving them a grace period to eke out grape maturity. It is for this reason that few 2024s taste vegetal.

The Harvest

By the time of harvest, winemakers just wanted to get it over and done with. Put the nightmare behind them and start anew. The new vintage is always less than 12 months away. This year, there was little difference between the starting dates of the whites and reds, around September 12 or 13 for the former, two or three days later for the latter, though several picked their whites after the more sensitive reds. That marks a change from the harvest firing gun sounding in August. Many pickings were completed in half the normal time because there was so little fruit. Those who sorted fruit in the vineyard took longer since they had to meticulously parse out mildew-affected berries.

There are markedly divergent opinions on whether sorting was necessary. Some winemakers, like Frédéric Barnier (Louis Jadot) and Mathilde Grivot, remarked that the fruit was healthy because mildew-affected berries had shrivelled and fallen to the ground. Others needed to ramp up sorting, fearing that mildew could lurk unseen inside bunches if it had attacked during fermeture, when the bunches close. You want to avoid what winemakers call “goûts moisis terreux,” or G.M.T., which, as Thibault Liger-Belair explained, is simply the taste of the mildew in the wine. It manifests as an unpleasant dustiness, as if someone had emptied their vacuum bag into your lovely Pinot Noir. Some domaines, like Château de la Tour, installed second vibrating tables or Mistral machines.

Vinification

Ask a winemaker how the vinifications went in 2024, and the default reply is: “simple.” Certainly easier than coping with 2023’s large volumes. But everything is relative, and I suspect it felt simple juxtaposed against the rollercoaster growing season. Though not affecting everyone, there were two fundamental questions regarding the vinification.

Filling Your Vats

The first, one doubtlessly foreseen as early as June, especially in the Côte de Nuits, was exactly how winemakers were going to fill their vats. If your vat room was already equipped with smaller tanks, you had an advantage. Some wineries, such as Mugneret-Gibourg, literally nipped down to the shops to purchase smaller-sized vats as harvest dawned. Vinifying wine in a half-empty vat poses all sorts of risks. Some winemakers simply vinified their smallest cuvées in barrel.

They all faced a dilemma: whether to blend regular cuvées together or keep them separate. Combine lieux-dits to create non-specific vineyard cuvées or retain the roster of Premier and Grand Crus your followers expect, albeit in minuscule quantities?

Thankfully, this is not the entire production from Ghislaine-Barthod in 2024. But I wonder if it might have been wiser to bite the bullet and blend the smallest cuvées?

Perhaps the most extreme example of this I encountered was Ghislaine-Barthod in Chambolle-Musigny, whose Premier Crus each comprise anywhere from two to six barrels in a normal year. In 2024, some of them were reduced to a feuillette—one-half of a barrel, or around 140 bottles. This was not the only case. Sylvain Pataille, Domaine d’Eugénie, Cécile Tremblay and Grivot are just a handful that could not countenance the idea of being down a cuvée. Some had no option. In the worst cases, winemakers eked out just two or three cases of fruit from some parcels, which verges on comical. Those who blended cuvées that were traditionally bottled separately include Duroché, Felettig, Comte Liger-Belair, Marquis d’Angerville, Maxime Rion, Mugneret-Gibourg and Simon Bize, amongst others. Suffice it to say that most Burgundy producers blend cuvées as a last resort. Knowing this all too well after 2016 and 2021, I never anticipated a significant reduction in the number of wines to taste.

However, the smaller the volume of must, the trickier it is to vinify, particularly for reds. The biggest challenge is controlling temperatures due to the lack of thermal inertia—maintaining temperature to control yeasts and prevent spoilage. Amélie Berthaut put a couple of barrels out in the sun to try and warm them up. Furthermore, as Carel Voorhuis at Camille Giroud explained, there is less weight of fruit, less pressure at the base of the vat, and this could induce more carbonic fermentation, which is not necessarily undesirable.

Vinifying a single barrel means you have no options, no flexibility to pick ‘n choose the best barrels. Funny how connoisseurs get weak-kneed contemplating single-barrel cuvées when notionally that is disadvantageous. Perhaps rarity is a more important virtue than taste. I have to say that when tasting through Ghislaine Barthod’s 2024s, I could tell the difference between cuvées reduced to feuillettes and those that still had two or three barrels. In tiny volumes, the wines themselves seem deprived of weight and depth, ephemeral wines that—attractive as they are—might blow away in the lightest breeze.

Knowing in advance that the fruit was lighter and more fragile compared to recent vintages, most maîtres-de-chai enacted a gentle extraction, eschewing punching down and conducting only light pumpovers. The one exception was at Domaine J-L Trapet, Pierre Trapet admitting that he went against the grain and dialled up extraction to compensate for any shortfall in concentration.

With Or Without Stems?

The second conundrum was whether or not to use whole bunches. If you always destem your bunches (Hudelot-Nöellat, Grivot, Méo-Camuzet inter alia), then there was no question. The increasing proportion of winemakers who do add stems had to consider the health of the bunches and to what degree they had been touched by mildew. If so, how confident were you in terms of eradicating these issues at the sorting table? There is no consensus. On one particular day in Vosne-Romanée, a winemaker confidently explained to me how he confidently used 100% whole bunch, while a second, barely an hour later, claimed that any stem addition was foolish since the juice did not have the mass to assimilate stems—unlike in 2020 or 2022.

Jae Chu is the new winemaker for Domaine d’Eugénie. We had an insightful exchange about the domaine’s use of whole bunch. She is also trialling Clayver in tandem with oak.

Who is correct?

Well, it really comes down to how well the stems appear subsumed into the wine and whether you are partial to those flavours. There is no hard and fast rule. I tasted 2024s with 100% stems where they were seamlessly interwoven, and others where the stems obscured fruit and terroir expression. The success of whole bunch is only ascertained in hindsight. You cannot go back and pull them out if you find their influence excessive, just hope and pray that they will integrate over time in a vintage that is not predisposed to long-term aging.

As a Burgundy lover with a penchant for whole bunch, based on tasting over 2,000 wines, 2024 was not a vintage to play recklessly with stems. A majority of winemakers concurred with that view and decided to eschew them. It was prudent to either lower the percentage of whole cluster, as did Gilbert Felettig and Cyprien Arlaud, or to avoid them altogether, like Jean-Marie Fourrier or the team at Rossignol-Trapet. That said, I admire the stand of those who refused to compromise, and in 2024, you can find some marvellous wines that use high levels of whole bunch. Winemakers such as Dujac, Lignier-Michelot, Chandon de Briailles, Hugo Bize and Armand Heitz used 100% stems across all their cuvées to varying degrees of success. Occasionally, the stems can dominate wines and leave them marked with vegetal or capsicum traits. Pascal Mugneret was one of the few who openly admitted that he took a risk; within his portfolio, there are hits and misses governed by stem assimilation.

This report includes the wines of Japanese winemaker Koji Nakada for the first time. He makes wine with his Korean-born wife, Jae Hwa. On the right, you can see the Clayver that they use in conjunction with traditional oak barrels.

“Don’t believe anyone who says that they did not have to add sugar in 2024,” Eric Germain told me, before several winemakers claimed they did not add sugar to the must. With alcohol levels lagging at around 11.5% to 12.5%, it is unsurprising that many did indeed chaptalize to bolster their wines and extend the length of fermentation.

Barrel Maturation

With respect to élevage, most winemakers dialled down the percentage of new oak. As several mentioned, that decision was made easy by the fact that many domaines had plenty of used barrels available after the 2023 vintage. Again, Pierre Trapet took the opposite view and used 100% new oak. Some winemakers, like Laurent Fournier and Benjamin Leroux, aged their 2024s in larger barrels. Then, there are glass WineGlobes and, more recently, the tentative introduction of ceramic Clayvers being trialled by the likes of Domaine d’Eugénie, J-L Trapet and Benjamin Leroux, albeit not the wholesale expulsion of traditional oak barrels à la Arnoux-Lachaux. Whilst I understand their use in tandem with oak, I find that these alternative vessels render Pinot Noir sterile and almost anaemic when used on their own. An enlightening comparative tasting of the same cuvée in Clayver and a one-year barrel reinforced my view, one shared with winemakers trialling ceramic vessels.

In terms of duration in barrel, some producers expressed a desire to bottle slightly earlier than usual, in December or January instead of spring. Others, like Sylvain Pataille, have been pleasantly surprised by how their gestating wines have gained weight in recent months and revised plans to now bottle later. Bottling is often the forgotten part of the winemaking process, but the 2024s are generally less robust wines, and timely/careful bottling will be absolutely crucial.

Olivier Lamy installed a new bottling line at the winery to ensure what he captures in the vineyard is also captured in the bottle.

How I Tasted the Wines

I tasted all the wines in this report between October 13 and November 21, 2025. I prefer not to taste later in the year, as cellars turn colder and barrel samples close up. I conduct this six-week “marathon” producer by producer, which is laborious and time-consuming. There is nothing more fascinating or fulfilling than amassing a wealth of information not only about the wines themselves, but the techniques and context behind them, never mind the multitude of on- and off-the-record discussions about goings-on behind the scenes.

Despite the raft of tiny yields in 2024, I anticipated that I would taste roughly the same number of wines as in previous years. The current tally of 2400+ will be augmented by three further days of tasting in Burgundy, including Roulot and Alex Moreau, plus tastings in London in January.

As always, I strive to embrace historical grandees such as Louis Jadot and Drouhin, the hallowed names like Domaine de la Romanée-Conti and Coche-Dury, and less-well-known producers from all appellations, regional to Grand Crus. It is impossible to include everyone, but I do my best. Readers will find Producer Commentaries attached to the tasting notes for every producer I visited—these are a trove of ground-level insight and information.

Like 2016 and 2021, 2024 is a complex vintage in terms of what was actually tasted. A missing tasting note is likely down to one of three reasons: 1) a wine was blended with another cuvée to make a non-vineyard-designated label, 2) volumes were too minuscule for producers to risk constantly opening the same barrel to draw samples or 3) the wine was not produced.

I have included explanations of what befell these missing cuvées within tasting notes. These lacunas are an integral part of the story, analogous to the spaces between musical notes. To put it prosaically, it will spare Vinous readers from searching for non-existent wines!

Finally, I did discern more instances of reduction amongst samples, which is to be expected, as some barrels were due to be racked. Perhaps this was compounded by a greater use of sulfur in the vineyards to fight oïdium, although I would have thought the rain had washed away any residues.

Arnaud Mortet demonstrates the new bottle size for his 2025s!

The Wines

We are really looking at two different growing seasons. Two fates. Never before have I encountered a vintage where there are such stark differences between the Côte de Beaune and Côte de Nuits, between white and red, to a lesser degree between limestone and clay soils. These differences extend beyond what is found in the wines and into the views expressed by winemakers and, indeed, how they look back on this infamous season.

Whites

The 2024 growing season favours whites over reds. Though the inclement conditions deprived winemakers of normal yields, they were not as pitiful as they were for Pinot Noir. Thanks to its inherent virtues—earlier ripening, thicker skin—plus its location in the less-rain-drenched Côte de Beaune, Chardonnay sidestepped the season’s pitfalls, exploiting the cooler climes to its advantage in terms of maintaining acidity and tension. Burgundy lovers lamenting the loss of acidic drive will love the 2024 whites due to higher levels of malic acidity. Boris Champy told me his 2022 and 2023 contained 1.2 grams per litre (g/l) of malic acid. In 2024, it was 4.5 g/l. These high malic levels infuse energy into the wines and could well safeguard a longer maturation in bottle than expected.

Several winemakers, including Champy, remarked that it was important to work with the lees, even using those from the previous vintage, in order to build more complexity into the whites. No single appellation rises above others, though clearly, vineyards located on the incline benefited from superior drainage to those in flat, humid areas. Theoretically, sites located on the incline had better exposure to the sun during those vital days in August.

Côte Chalonnaise – I only had time to visit three or four producers in the Côte Chalonnaise. Next year, I hope to dedicate a few days to the region. However, the 2024s here are well worth investigating since the region suffered less rainfall than the Côte d’Or. Of course, Dureuil-Janthial fashioned some exceptional wines, but there is a hotbed of talent taking root, partly as the Côte d’Or has become unaffordable.

Saint-Aubin – Saint-Aubin was severely impacted by precipitation, frost and hail. However, this is Chardonnay country, so winemakers were still able to squeeze out small quantities of splendid Premier Crus. Site and producer are particularly important for buying decisions in this inconsistent year.

Chassagne-Montrachet – Bolstered by Chardonnay and a plethora of winemakers at the top of their game, Chassagne-Montrachet is a trove of compelling whites that I find to be shaped quite Puligny-like in style, more tensile and malic compared to 2022 or 2023. The best 2024s tend to be from limestone soils on the incline: La Romanée, La Grande Montagne, En Cailleret, etc.

Benoît Riffault at Etienne Sauzet, presenting his 2024s on the first day of my trip.

Puligny-Montrachet – Twenty-four is a potentially great year for this appellation. Many overcame the challenges and exploited the cooler conditions, yielding sometimes razor-sharp, mineral/terroir-driven wines. This year, there is a tangible gap between Premier and Grand Crus. Bâtard-Montrachet excelled, likewise Premier Crus such as Les Folatières and Champ Canet.

Meursault – Like Chassagne, 2024 produced less weighty, less sun-kissed Chardonnays so that some err towards Puligny in style. The season heightened the mineral core of Les Perrières, whilst propitious climats such as Les Charmes and Le Porusot performed with aplomb.

Corton-Charlemagne – Zoning in on the hill around Corton, this is the usual hits ‘n misses. The challenge here was to obtain the texture and weight expected of a Corton-Charlemagne, what is referred to as “gras.” Without those, this Grand Cru can be rendered a bit nondescript, a fate that befell some growers.

Reds

The reds took the brunt of the tumultuous growing season. As such, they are ineluctably inconsistent, not only from producer to producer, but even within producers’ portfolios. A sensitive grape variety like Pinot Noir is born to translate the vicissitudes of any growing season, and it could not disguise what some described as “…the rainiest in living memory.” Perversely, I respect that this variety upholds a moral duty to reflect not only the positives but also the negatives.

The first thing that will strike you is the colour of the wines. These are some of the palest young Burgundy reds I can remember, though colour has no bearing upon my assessment. Some of the greatest Pinot Noirs I’ve ever tasted have looked anaemic.

The 2024s have very attractive aromatics. In fact, there is a strong case for the season disproportionately affecting the palate, where many of the Côte de Nuits wines lack depth, substance and length. At worst, they can seem hollow and attenuated, shorn of the flesh and weight commonly found in hot vintages like 2018 or 2022. The 2024s are occasionally a bit rustic with hard edges, though some will smooth out during their second winter in barrel or with bottle age. That said, these are not candidates for long-term cellaring.

Let’s look at the positives, because mildew does not directly affect quality. First and foremost, 20 years ago, most vineyards would have succumbed to such a torturous vintage. Winemakers would have thrown in the towel, and that is partly because back then, potential returns were much lower. Though the wines are inconsistent, there are remarkably few incidences of underripeness. Rarely did I jot the word “green” when tasting. That is primarily thanks to the fortnight of favourable weather leading up to harvest, coupled with the sun’s energy directed upon the fewer bunches hanging, which rewarded some wines with tantalising tension. In some instances, it led to surprisingly ripe wines that occasionally taste as if they were born in a completely different growing season. Some winemakers described their 2024s as “concentrated.” I disagree. That is taking it too far. That said, many at the top level achieved a purity of fruit that has much more intensity than predicted.

Secondly, how joyful to taste wines that resolutely reside in the red side of the fruit spectrum, where Pinot Noir reaches its apogee. Strawberry, cranberry, redcurrants, pomegranate and red cherries…how often did I type those fruit aromas and flavours? Behind them, glimpses of wilted rose petals, rooibos and bergamot. These are traits that I—and many Burgundy lovers—covet, and why the 2024s should not be dismissed before tasting.

Freshness. Unsurprisingly, in a season without prolonged heatwaves, acidity levels are relatively high, so these 2024 reds have plenty of freshness and zing. This derives from higher malic levels than tartaric, which surprised some winemakers. It gives the wines what the French call “buvabilité.” The wines are easygoing and untaxing to drink, especially at their lower alcohol levels, mainly between 12.5% and 13.0%, with a few reaching 13.5%. The knock-on effect is that this lends the best wines transparency and terroir expression. One intermittent trait is that some of the 2024 reds can give the false impression of containing stems when there are none—a tantalising pepperiness on the finish and aftertaste. Charles Magnien cited the high percentage of pip to juice that imparts this natural pepperiness, to which I am quite partial.

That in itself makes the 2024s fascinating to taste. The deficiencies and attributes kept my palate on its metaphorical toes, instead of encountering one extremely ripe wine after another.

Santenay – Jean-Marc Vincent told me that rainfall was just a little lower in Santenay than average, and this is borne out with some classy wines from this overlooked and competitively priced appellation.

Volnay – The appellation tends to be compared to neighbouring Pommard, and in 2024, I feel that Pommard fared a little better. The inclement conditions shorn the Volnay wines of their roundness and sensuality, so whilst there remain some that buck the trend, even my favourites felt sapped of joie de vivre.

Pommard – This is an appellation to keep an eye on. Though overshadowed by Volnay in recent years, when comparing the two together within growers’ portfolios of 2024s, I often preferred Pommard over Volnay. Out of the direct firing line of the worst rainfall excesses, there are some very worthy 2024s from this appellation.

Beaune – Connoisseurs turn their noses up at Beaune, presumably because of its association with négociants, a lack of superstar names, and market prices. The fact is that Beaune is a treasure trove in plain sight, and like Pommard, just outside of the worst rainfall. There are some delightful 2024s from Beaune’s more propitious vineyards, like Clos des Mouches and Les Grèves.

Savigny/Aloxe/Ladoix – A bit patchy, to be frank. Savigny, in particular, has a cluster (no pun intended) of growers who remained loyal to 100% whole bunch. If you like that style, growers like Bize and Chandon des Briailles are worth hunting down, although volumes are minuscule and many cuvées are M.I.A.

Nuits Saint-Georges – This appellation was severely impacted by the rainfall, which deprived even the most notable winemakers of either their usual quality or entire cuvées. However, Domaine Robert Chevillon proved it was possible to grasp victory in spite of everything.

Vosne-Romanée – It may be the most prestigious appellation, but it faced the onslaught of inclement conditions in 2024. This was counterbalanced by the fact that growers here have more resources and could afford to implement measures to fight mildew pressure, plus the equipment and wherewithal to rigorously sort at reception. Volumes are tiny. What survived can be glorious, but it is far patchier than usual. It should be said that Clos Vougeot actually fared better than expected in 2024, and there are several examples worth seeking out.

Chambolle-Musigny – The 2024 vintage hammered this appellation. It is very heterogeneous in quality, even within reputed growers’ ranges. This is compounded by the smaller parcels that tend to form Chambolle’s Premier Crus, which reduced many cuvées to single barrels or feuillettes and rendered some normally standout cuvées rather ephemeral.

Morey-Saint-Denis – In 2024, this appellation seemed to fare better than Chambolle-Musigny. The wines tend to be a bit stouter and denser, ergo they withstood the shortfalls of the growing season and in some cases come across less austere than usual. This is definitely an appellation to pay close attention to.

Gevrey-Chambertin – Again, this is a patchy set of wines whose quality depends on where you are located, on the plain or on the incline, Village or Grand Cru. It took the brunt of the rainfall, and vineyard teams had to persevere throughout the season. Like Chassagne-Montrachet, there is a roster of exceptional winemakers who faced the challenge head-on and almost miraculously made splendid, often elegant and refined wines. Perhaps in 2024, there is not a gulf of qualitative difference between Premier and Grand Crus.

Fixin/Marsannay – This is another appellation to examine closely because it suffered less rainfall than Gevrey to the south. Fixin is hampered by the lack of top-grade growers, but again, Amélie Berthaut showed what was possible. Marsannay is an appellation that is often unfairly overlooked, probably due to the lack of Premier Crus, but unlike Fixin, Marsannay is home to a number of talented winemakers, such as Arthur Clair, Laurent Fournier and Sylvain Pataille. Jean-Pierre Roty is an honorary addition, as a majority of his vineyard holdings are located in Marsannay.

Final Thoughts

The more challenging the growing season, the more there is to write about. My summary is lengthy because it is easier to list events that did not happen than those that did. The cavalcade of pernicious events tested the mettle of every winemaker. Paul Thomas Anderson’s brilliant movie, One Battle After Another, seemed apposite to the growing season.

That is what it was.

That is how it felt.

Each winemaker reacted differently. Indeed, one noted how the extremity of the season coaxed more contact with fellow beleaguered winemakers to find out how they were coping—anxiety partially assuaged by the thought of not being alone. Twenty-four was a battle fought by one and all.

Twenty-four can lay little claim to being a great Burgundy vintage. However, it is better than many envisaged as they trudged through the vines on yet another rainy day. That stint of sunny August weather was a silver lining that enabled some to capture the brightness and freshness of vibrant red fruit where Pinot Noir reaches its apex. It imbued many Chardonnays with razor-sharp tension and delineation that will attract admirers. Nevertheless, the reds do not possess tremendous substance or grip. In place of genuine depth is that coveted virtue of transparency, and as such, the wines will be catnip in the short term. Maybe they will fade after the first decade. Since longevity is a precept for quality, this is reflected in my scores.

Scores be damned! I like many of the 2024s. They will be compared to the 2021s, but I believe the 2024s are better.

One written quote on Domaine Joseph Voillot’s vintage summary struck home: “Wine gets better with time. But this year will only get better with wine.”

That sums up 2024. As Mother Nature corroded potential yields, many suffered the dispiriting feeling of working hard for no return. But eventually, winemakers came away with a small amount of wine they can be proud of, a testament to resilience and fortitude. The season reinforced the unsettling thought of contending with unpredictable and extreme weather. Winemakers pray that they never have to suffer a season like this again. That cannot be written off.

The vintage raised more questions about the implications for global warming. It challenged the viability of organic viticulture, the use of whole bunch, even the financial viability of making wine, not least for family-owned domaines, as outside investors wave life-changing amounts under their noses for slivers of land. Though the Côte d’Or survived 2024, its destiny might have shifted. During my time in the region, I got the palpable sense of winemakers still recovering from the growing season, a reminder of how nature can be merciless. This is concurrent with a shifting landscape—numerous domaines where batons are being handed to the next generation, their careers starting in a completely different environment from their parents’. Perhaps 2024 has steeled these newcomers against future malevolent seasons.

The bottom line is that 2024 is an endlessly fascinating vintage that will enamour the small number who imbibe the fruits of much labour.

© 2026, Vinous. No portion of this article may be copied, shared or redistributed without prior consent from Vinous. Doing so is not only a violation of our copyright but also threatens the survival of independent wine criticism.

You Might Also Enjoy

The Lord Giveth…Burgundy 2023, Neal Martin, January 2025

Burgundy 2023: The State of Play, Neal Martin, January 2025

Burgundy 2023 Videos, Neal Martin, January 2025

Now, For My Latest Trick: Burgundy 2022, Neal Martin, January 2024

Servants of the Season: Burgundy 2021, Neal Martin, January 2023

Dance the Quickstep: Burgundy 2020, Neal Martin, December 2021

Show all the wines (sorted by score)

- Albert Bichot

- Albert Bichot (Château Gris)

- Albert Bichot (Domaine du Clos Frantin)

- Albert Bichot (Domaine du Pavillon)

- Alex Moreau

- Alvina Pernot

- Armand Heitz

- Arnaud et Sophie Sirugue-Noellat

- Arnaud Mortet

- Ballot-Millot & Fils

- Benjamin Leroux

- Benoît & Jean-Baptiste Bachelet

- Camille Giroud

- Charles Boigelot

- Château de la Tour

- Château de Marsannay

- Château de Pommard

- Christophe Roumier (Domaine Georges Roumier)

- Cyprien Arlaud

- Domaine Agnès Paquet

- Domaine Alain Burguet

- Domaine Alexandre Parigot

- Domaine Aline Beauné

- Domaine Amiot-Servelle

- Domaine Anne Gros

- Domaine Anne Morey

- Domaine Anne Parent

- Domaine Antoine Jobard

- Domaine Antonin Guyon

- Domaine Arlaud

- Domaine Armand Rousseau

- Domaine Bachelet-Monnot

- Domaine Benoît Moreau

- Domaine Bernard & Thierry Glantenay

- Domaine Berthaut-Gerbet

- Domaine Berthelemot

- Domaine Bertrand et Axelle Machard de Gramont

- Domaine Bitouzet-Prieur

- Domaine Boigey

- Domaine Boris Champy

- Domaine Bouchard Père & Fils

- Domaine Bruno Clair

- Domaine Camus-Bruchon & Fils

- Domaine Cécile Tremblay

- Domaine Chandon des Briailles

- Domaine Changarnier

- Domaine Chanson

- Domaine Chapelle de Blagny

- Domaine Chevrot

- Domaine Christian Sérafin

- Domaine Claude Dugat

- Domaine Claudie Jobard

- Domaine Clos de Tart

- Domaine Comte Armand

- Domaine Comte Georges de Vogüé

- Domaine Coquard Loison Fleurot

- Domaine David Moreau

- Domaine de la Choupette

- Domaine de la Commaraine

- Domaine de la Folie

- Domaine de la Monette

- Domaine de la Pousse d'Or

- Domaine de l'Arlot

- Domaine de la Romanée-Conti

- Domaine de la Vougeraie

- Domaine de Montille

- Domaine Denis Bachelet

- Domaine Denis Mortet

- Domaine des Cabottes

- Domaine des Chezeaux

- Domaine des Comtes Lafon

- Domaine des Croix

- Domaine des Lambrays

- Domaine Desvignes

- Domaine d'Eugénie

- Domaine de Villaine

- Domaine Dominique Gallois

- Domaine Dominique Guyon

- Domaine Drouhin-Laroze

- Domaine Dubreuil-Fontaine

- Domaine du Cellier Aux Moins

- Domaine du Comte Liger-Belair

- Domaine du Couvent

- Domaine Dujac

- Domaine Dureuil-Janthial

- Domaine Duroché

- Domaine Elodie Roy

- Domaine Emmanuel Rouget

- Domaine Eric Boigelot

- Domaine Etienne Sauzet

- Domaine Fabien Coche

- Domaine Faiveley

- Domaine Felettig

- Domaine Fernand & Laurent Pillot

- Domaine Florence Cholet

- Domaine Follin-Arbelet

- Domaine Fontaine-Gagnard

- Domaine Fourrier

- Domaine François Buffet

- Domaine François Carillon

- Domaine Françoise & Denis Clair

- Domaine François Lumpp

- Domaine François Raquillet

- Domaine Genot-Boulanger

- Domaine Georges Glantenay

- Domaine Georges Noëllat

- Domaine Georges Roumier

- Domaine Gérard Mugneret

- Domaine Ghislaine-Barthod

- Domaine Gilles Morat

- Domaine Guerrin et Fils

- Domaine Guy Roulot

- Domaine Henri Germain

- Domaine Henri & Gilles Buisson

- Domaine Henri Gouges

- Domaine Henri Magnien

- Domaine Henri Rebourseau

- Domaine Heresztyn-Mazzini

- Domaine Hubert Lignier

- Domaine Hubert & Olivier Lamy

- Domaine Hudelot-Baillet

- Domaine Hudelot-Noëllat

- Domaine Humbert Frères

- Domaine Jacques Carillon

- Domaine Jacques Dury

- Domaine Jean-Baptiste Boudier

- Domaine Jean Chartron

- Domaine Jean-Claude Bachelet

- Domaine Jean et Jean-Louis Trapet

- Domaine Jean Fournier

- Domaine Jean-François Coche-Dury

- Domaine Jean Grivot

- Domaine Jean-Marc Boillot

- Domaine Jean-Marc Pavelot

- Domaine Jean-Marc Vincent

- Domaine Jean-Michel Gaunoux & Fils

- Domaine Jean-Noël Gagnard

- Domaine Jean Tardy

- Domaine Jérôme Fornerot

- Domaine Jérôme Galeyrand

- Domaine J-F Mugnier

- Domaine JJ Confuron

- Domaine Joseph Colin

- Domaine Joseph Drouhin

- Domaine Joseph Pascal

- Domaine Joseph Roty

- Domaine Joseph Voillot

- Domaine Koji et Jae Hwa

- Domaine Lamy-Caillat

- Domaine Launay-Horiot

- Domaine Legros

- Domaine Le Guelle-Ducouet

- Domaine les Astrelles

- Domaine Louis Boillot et Fils

- Domaine Maillard Père & Fils

- Domaine Marc Colin

- Domaine Marchand-Grillot

- Domaine Marc Morey & Fils

- Domaine Marc Roy

- Domaine Mark Haisma

- Domaine Marquis d'Angerville

- Domaine Méo-Camuzet

- Domaine Michel Bouzereau

- Domaine Michèle & Patrice Rion

- Domaine Michel Gros

- Domaine Michel Lafarge

- Domaine Michel Mallard

- Domaine Michel Niellon

- Domaine Morey-Coffinet

- Domaine Mugneret-Gibourg

- Domaine Nicolas Faure

- Domaine Nicolas Maillet

- Domaine Patrick Javillier

- Domaine Paul et Marie Jacqueson

- Domaine Paul Pernot

- Domaine Paul Pillot

- Domaine Pernot Belicard

- Domaine Perrot-Minot

- Domaine Pierre Gelin

- Domaine Pierre Labet

- Domaine Pierre Vincent

- Domaine Pierre-Yves Colin Morey

- Domaine Pierrick Bouley

- Domaine P&L Borgeot

- Domaine Ponsot

- Domaine Rapet Père & Fils

- Domaine Rebourgeon-Mure

- Domaine Rémi Jobard

- Domaine Robert Chevillon

- Domaine Robert Groffier

- Domaine Roblot-Marchand

- Domaine Rollin Père & Fils

- Domaine Rossignol-Février Père & Fils

- Domaine Rossignol-Trapet

- Domaine Simon Bize

- Domaine Sylvain Cathiard

- Domaine Sylvain Dussort

- Domaine Sylvain Langoureau

- Domaine Sylvain Pataille

- Domaine Sylvie Esmonin

- Domaine Taupenot-Merme

- Domaine Thibaut Liger-Belair

- Domaine Thierry & Pascale Matrot

- Domaine Tollot-Beaut

- Domaine Tortochot

- Domaine Xavier Monnot

- Domaine Y. Clerget

- Edouard Delaunay

- Henri Boillot

- Hubert Lignier

- Hugues Pavelot

- Icy Lui

- Jane Eyre

- Jean-Pierre Guyon

- JJ Archambaud

- Laroze de Drouhin

- Les Héritiers du Comte Lafon

- Louis Chenu & Fils

- Louis Jadot (Domaine)

- Louis Jadot (Domaine des Héritiers Jadot)

- Louis Jadot (Domaine Duc de Magenta)

- Louis Jadot (Domaine Gagey)

- Louis Jadot (Domaine Prieur-Brunet)

- Louis Jadot (Famille Gagey)

- Louis Jadot (Maison)

- Maison de Montille

- Maison Harbour

- Maison Henri & Gilles Buisson

- Maison Joliet

- Maison Lou Dumont

- Marchand-Tawse

- Marchand-Tawse (Vignes de la Famille Tawse)

- Mark Haisma

- Maume-Siblas

- Maxime Cheurlin Noëllat

- Méo-Camuzet Frère & Soeur

- Morey Blanc

- Olivier Guyot

- Patrice Rion

- Pierre Girardin

- Pierre & Louis Trapet

- Pierre & Marianne Duroché

- Pierre-Olivier Garcia

- Seguin-Manuel

- Seguin-Manuel (Domaine)

- Simon Colin

- Théo Dancer

- Vincent Girardin

- Virgile Lignier-Michelot