Browse using the new Vinous website now. Launch →

Printed by, and for the sole use of . All rights reserved © 2015 Vinous Media

72 Henry Street

Brooklyn, NY 11201

BY NEAL MARTIN | APRIL 25, 2025

The Food:

New Orleans turtle soup

Goose liver mousse with pistachios and honey

Squab potstickers with chilli garlic sauce

Pappardelle with Buffalo oxtail ragu

Stuffed quail with cornbread and sausage stuffing

Kangaroo with gratin dauphinois and Burgundy jus

Elk chops with mushroom bread pudding

The Wines:

1997 Nicolas Joly Savennières Clos de la Coulée de Serrant – 90

1978 Burgess Cellars Cabernet Sauvignon Napa Valley – 89

1961 Giuseppe Mascarello Barbaresco – 91

1980 L’Eglise-Clinet – NR

2005 Domaine Georges Roumier Morey-Saint-Denis Clos de la Bussière 1er Cru – 93

2002 J. Rochioli Pinot Noir West Block – 92

1999 d’Arenberg Winery The Ironstone Pressings – 92

1927 Pereira d’Oliveira Bastardo Madeira – 94

Neighbourhood institution. That phrase can be interpreted in two ways. On the one hand, it implies that over time, a restaurant became part of the local fixture and fittings. Its heyday might be long gone, yet there continues to be a steady stream of regulars that covet familiarity, whose taste buds are indifferent towards quality. The epitome is an Italian bistro near my parents’ home that has existed in the same place, serving the same clichéd dishes and cheap Chianti from the local cash and carry since time immemorial. The irony is that this bistro has outlived every other restaurant within a 10-mile radius.

On the other hand, neighbourhood institution connotes a restaurant where high standards and passionate, talented chefs with attention to detail have sustained it through the years, a restaurant that stands as a beacon of quality. A restaurant that becomes a constant in a turbulent world. It is irreplicable and irreplaceable. Now, I never dined at Henry’s End when it opened in 1973 because (a) I was two years old and (b) I lived in Leigh-on-Sea, not Brooklyn. Nevertheless, invited by friends preceding this year’s Vinous Icons event in New York, my tastebuds immediately confirmed that Henry’s End falls into the latter category of neighbourhood institutions. In other words, it might have opened over half a century ago, but standards remain high and people still love it.

Proprietor Mark Lahm posing in front of the neon signage above the stairs.

The name Henry’s End comes from the restaurant’s location up until 2019, when it sat two blocks north of Henry Street, ergo, at the “end” of Henry. Bustling on a Wednesday night, the restaurant brims with history, character and above all, delicious food. “I have worked here since 1980, starting as a dishwasher, then server, manager, cook and chef,” Co-owner Mark Lahm told me. “In 1984, I enrolled in the Culinary Institute of America, and when I graduated in 1986, I purchased the restaurant from the previous owners. Our annual ‘Game Festival’ is now in its 39th year and runs from approximately October to April. It is done in three phases, two months for each phase, with the selections changing for each.”

To be honest, I wasn’t sure that I was in the mood for their Wild Game Festival, however, the quality of the first dishes immediately changed my mind and I was happy to go all-out carnivore. “We have used many different farms over the years,” Lahm explains. “Currently, our major suppliers are The Broken Arrow Ranch, Fossil Farms, d'Artagnan and Cervena.” In this case, I don’t need to analyse every dish, because they are all fairly straightforward. They highlight well-sourced ingredients and a kitchen that knows how to cook them perfectly. What I really appreciate is that despite the bias towards meat, no dish could be described as heavy—no excessive richness or pointless sauces. The United States is a country renowned for portions that could feed a small country, but here the portions are modestly sized, just right for a multi-course meal.

The New Orleans turtle soup is quite charmingly served in a coffee mug.

I must point out the New Orleans turtle soup. It is the first time I’ve eaten this dish, here made with 15 spices. It has real depth of flavour and just the right amount of spicy kick. A small cupful is just enough.

The goose liver mousse is topped with pistachios and honey and served with charred bread.

The goose liver mousse is sweet and creamy in texture and needs the accompanying charred bread to offset the richness. I have to resist eating the entire portion and mopping my plate. Next up, the pappardelle with Buffalo oxtail ragu is well cooked but perhaps could benefit from a little more of the nicely seasoned oxtails.

The stuffed quail was my favourite course of the evening.

The stuffed quail with cornbread and sausage stuffing is my highlight. Delicious and tender, the cornbread lends texture and sweetness, and the stuffing adds strong herbal flavours that marry perfectly with the quail.

Kangaroo made for an unusual but exquisite main course.

The kangaroo was imported from Australia (I did ask whether they are reared in the US—apparently not) and served with gratin dauphinois and Burgundy jus. This is tender and moist, and the jus has a light acidity that helps the dish maintain balance. I prefer this to the elk chops, which are slightly tough, especially following the kangaroo.

The wine list… I mean, you don’t see ‘em like that anymore. Many of the choice items come from the proprietor, who owns a vast personal cellar and negotiates favourable rates from private sources. The list is particularly strong in mature vintages from California, Bordeaux and Italy, especially esoteric vintages that you don’t typically see. This is a list for the wine-lover, not the label-hunter, and to cap it all off, most are sold at prices that would be three or four times as much elsewhere, if listed at all.

We actually begin with a very old sherry. You would expect sherry at the end of the meal, but its dagger-like acidity cleanses the palate. Apologies, but I did not write down the exact name, though it was extremely old.

The 1997

Savennières Clos de la Coulée de Serrant from Nicolas Joly is a

burnished golden hue. The nose is a little smudged, leaning more towards the

richer side of Savennières with dried honey, candlewax and lanolin. The palate

has fine weight and just a very slight touch of oxidation, though it complements

this wine. With just a touch of desiccated orange peel and some resinous notes

towards the end, this is definitely one of the better mature bottles I have

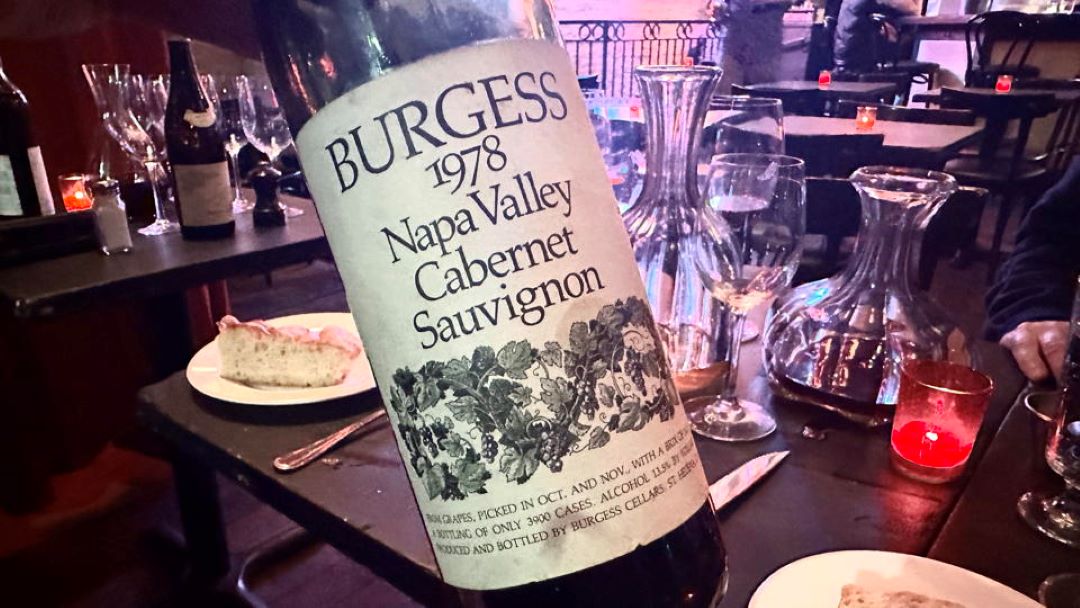

encountered from a wine that, in my experience, has been hit and miss. The 1978

Napa Valley Cabernet Sauvignon from Burgess Cellars is a delight.

Fully mature on the nose like many Cabernets from this era, it is a

doppelgänger for a Médoc, with sous-bois and light tobacco scents that

tinge vestiges of black fruit. The palate does not deliver the complexity of

the ’77 Diamond Creek Volcanic Hill imbibed the previous evening, though this

does retain balance and finesse. It’s perhaps a little simple or rather…unassuming

towards the finish, as if it has done its job well and now it’s time to leave.

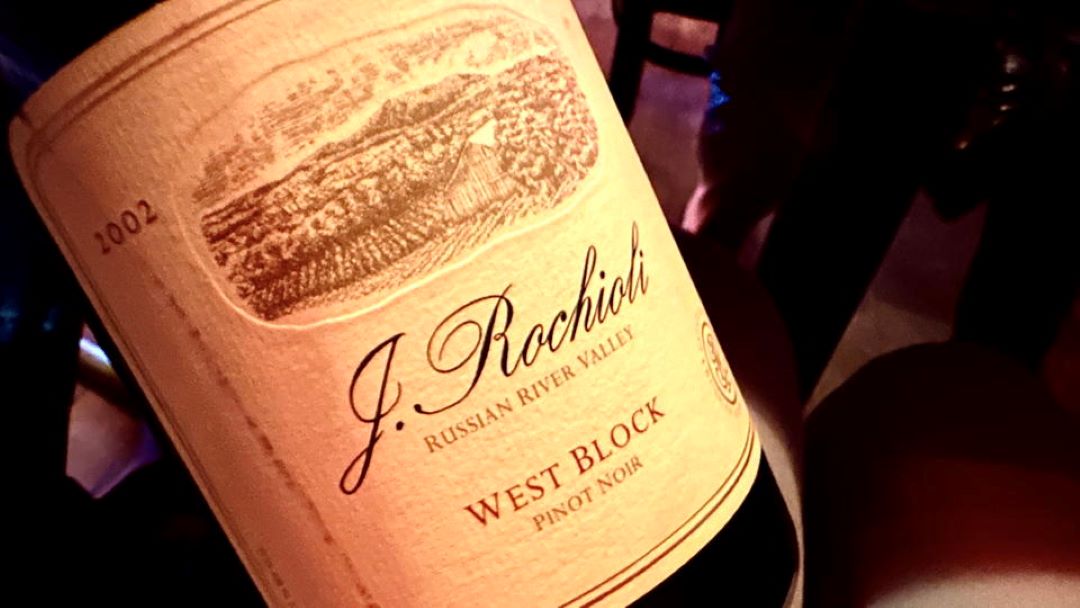

Not one of those earth-shattering old Californians, but decent. The 2002

West Block Pinot Noir from J. Rochioli initially seems a bit garish,

perhaps due to its juxtaposition against the ’78 Burgess. However, it just

needs 30 minutes to settle. It delivers gorgeous red plum, hoisin, camphor and

maraschino cherries that are beautifully defined and pure, generous but not

overpowering, distinct from Burgundy or anywhere else. The palate has wonderful

balance. It’s full-bodied, yet beneath what after two decades bizarrely feels

like puppy fat, one finds a core of fine tannins. Very harmonious, satin-textured

and persistent through the finish, this is a sensual and opulent Pinot Noir

that reeks of class.

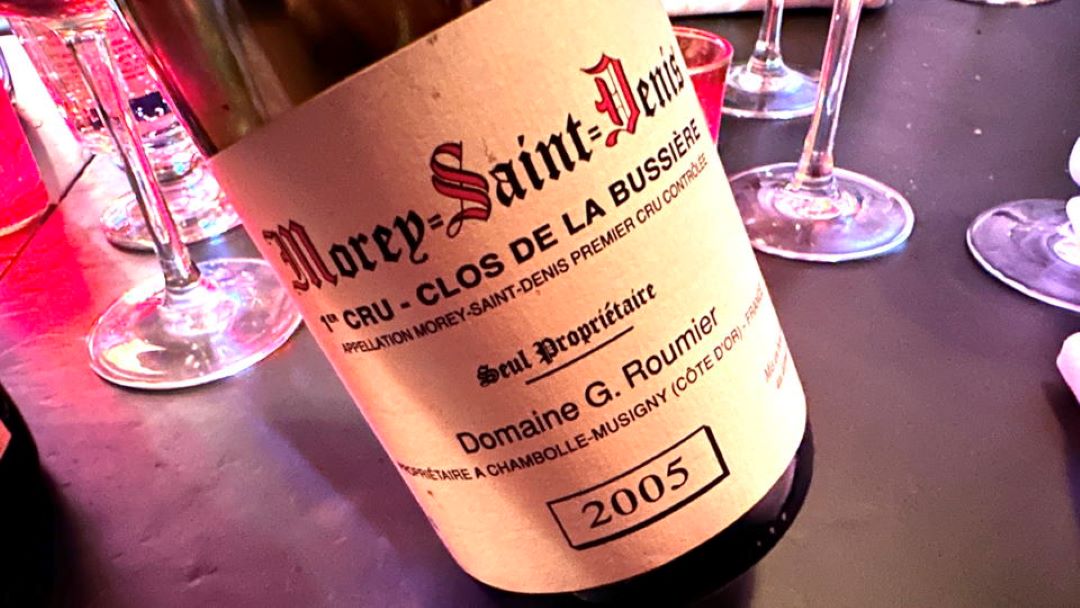

The 2005

Morey-Saint-Denis Clos de la Bussière 1er Cru from Domaine Georges Roumier

proves that this vintage produced some really classy wines whose tannins are

finally softening. It boasts exquisite purity on the nose, blossoming with white-tipped

strawberry, raspberry, crushed rose petals and wet limestone, polished and

sophisticated. The palate is framed by filigree tannins that, if tasted blind,

divert you away from this typically structured vintage. There is gentle but

insistent grip towards a finish that is imbued with the grip you expect from a

Morey rather than a Chambolle. This is beginning to take flight. We skip a 1980

L’Eglise-Clinet as the bottle is oxidised. Shame, as it is one of the very

few vintages that I’ve never tasted, and I doubt there is one at the château.

The 1961

Barbaresco from Giuseppe Mascarello is a rare old bird. It has a

pale colour, to the point that you would think it’s a Rosé. The nose has a

disarming citric quality, unerringly fresh, though I could never describe it as

complex. The palate is similar to the aromatics: very fresh and precise, arguably

missing grip and body that must have slipped away with time (indeed, this

bottle shed an extraordinary amount of sediment). This is more a curiosity now,

but a drinkable curiosity. The 1999 Ironstone Pressings from d’Arenberg

is a timely reminder of how well these Aussie wines have aged. This GSM exudes vigour

and purity on the nose, showing black plum mixed with subtle cough candy and lavender.

It is very controlled with ample refinement, perhaps “contained” by the passing

26 years. The palate remains fresh and vital, very well balanced with saturated,

smooth tannins, polished and graceful towards the finish. A gem hiding in plain

sight!

Later that evening, we are treated to a clutch of fortified wines. I will save a couple for Cellar Favourites and mention one. The 1927 Bastardo from Pereira d’Oliveira is nowadays quite difficult to track down, though I have encountered it two or three times in the past. It feels a little more austere than before, with potent, resinous, furniture polish scents. But then the fruit comes out of its slumber, revealing desiccated orange peel, tangerine and light smoky notes. Great vigour. The palate is medium-bodied with quite firm grip, tangy and vibrant with that grilled walnut/hazelnut note on the finish. It does not have the same “braggadocio” as previous bottles, but at a century-old, it continues to ooze class.

Henry’s End is a wonderful bistro, a neighbourhood institution in the best sense of the word. Both the food and wine will tempt me to return whenever I find myself back in the Big Apple. Whether it will outlive that Italian spot near my parents’ house is another question entirely, but I can promise that unless you do have a craving for rancid, cheap Chianti, head for the bounty of amazing wines at Henry’s End.

© 2025, Vinous. No portion of this article may be copied, shared or redistributed without prior consent from Vinous. Doing so is not only a violation of our copyright but also threatens the survival of independent wine criticism.